What is Building Work?

According to Schedule 2 of the Queensland Building Services Authority Act 1991, ("QBSA Act"), "building work" means:

- The erection or construction of a building.

- The renovation, alteration, extension, improvement or repair of a building.

- The provision of lighting, heating, ventilation, air-conditioning, water supply, sewerage or drainage in connection with a building.

- Any site work (including the construction of retaining structures) related to work of a kind referred to above.

- The preparation of plans or specifications for the performance of building work.

- Contract administration carried out by a person in relation to the construction of a building designed by the person.

- The installation, maintenance, or certification of the installation or maintenance, of a fire protection system for a commercial or residential building.

- Carrying out site testing and classification in preparation for the erection or construction of a building on the site.

- Carrying out a completed building inspection.

- The inspection or investigation of a building, and the provision of advice or a report, for the following:-

(a) Termite management systems for the building; and

(b) Termite infestation in the building; but does not include work of a kind excluded by regulation from the ambit of this definition.

Examples of what constitutes "building work" under the QBSA Act

- Construction of duplexes including external works and landscaping constitutes building work: Holland-Stolte Pty Ltd v Mirvac Projects Pty Ltd (unreported, NSWSC, 14 June 1991);

- Alteration – this is a question of fact. In Symond v Anor v North Sydney Municipal Council (unreported, NSWCA, 20 May 1988), the building work required the demolition and rebuilding of the whole of the interior, and roof of a building along with underpinning of foundations and retaining walls. This was held to be a total rebuilding, not an alteration; In Keane v Salisbury City (1996) 92 LGERA 114, adding a verandah onto premises comprised the making of a building alteration and therefore fell within the meaning of building work.

- A house constructed away from a site and then placed on stumps on the site constitutes building work: Hewett v Court (1983) 149 CLR 639;

- Any building which contains a commercial element (eg guest house) does not fall within the ambit of "home" or "domestic building work": Melcrest Communications Pty Ltd v Maleny Unit Trust (Unreported, QBT, 2 September 1996);

- Parties to a dispute arising under a building contract cannot dissect the contract into elements that constitute "building work" and those that don’t, for the purpose of making an application to oust the jurisdiction of the Tribunal: Freedom Homes (QLD) Pty Ltd v Jilek (Unreported, QBT, 9 April 1996);

- Construction of a mobile home was found to constitute building work in Nicholson v Norton (unreported, Magistrates Court, Inala, No. 7655 pf 1986);

- Management and supervision of those involved in day to day building operations: Lewoski and Ors v Lilley [2000] WASCA 14;

- Landscaping work: Brecknell v Sharrock Builder Walls and Steps – Proprietor – Keith Sharrock [2001] QBT 62.

What is Construction Work?

According to Section 10 of the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 ("BCIPA"), "construction work" means:-

- The construction, alteration, repair, restoration, maintenance, extension, demolition or dismantling of buildings or structures, whether permanent or not, forming, or to form, part of land.

- The construction, alteration, repair, restoration, maintenance, extension, demolition or dismantling of any works forming, or to form, part of land, including walls, roadworks, power-lines, telecommunication apparatus, aircraft runways, docks and harbours, railways, inland waterways, pipelines, reservoirs, water mains, wells, sewers, industrial plant and installations for land drainage or coast protection.

- The installation in any building, structure or works of fittings forming, or to form, part of land, including heating, lighting, air-conditioning, ventilation, power supply, drainage, sanitation, water supply, fire protection, security and communications systems.

- The external or internal cleaning of buildings, structures and works so far as it is carried out in the course of their construction, alteration, repair, restoration, maintenance or extension.

- Any operation that forms an integral part of, or is preparatory to or is for completing, work of the kind referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c), including –

- The painting or decorating of the internal or external surfaces of any building, structure or works.

- Carrying out the testing of soils and road making materials during the construction and maintenance of roads.

- Any other work of a kind prescribed under a regulation for this subsection. By virtue of Section 10(a) BCIPA, construction work includes building work within the meaning of the QBSA Act.

(a) site clearance, earth-moving, excavation, tunnelling and boring;

(b) the laying of foundations;

(c) the erection, maintenance or dismantling of scaffolding;

(d) the prefabrication of components to form part of any building, structure or works, whether carried out on-site or off-site; and

(e) site restoration, landscaping and the provision of roadways and other access works.

What are related goods and services?

According to Section 11 of the BCIPA, "related goods and services" means:-

- Goods of the following kind:-

- Services of the following kind:-

- Goods and services, in relation to construction work, of a kind prescribed under a regulation for this subsection.

(a) materials and components to form part of any building, structure or work arising from construction work; and

(b) plant or materials (whether supplied by sale, hire or otherwise) for use in connection with the carrying out of construction work.

(a) the provision of labour to carry out construction work;

(b) architectural, design, surveying or quantity surveying services relating to construction work; and

(c) building, engineering, interior or exterior decoration or landscape advisory services relating to construction work.

Under the BCIPA, "construction work" is defined more broadly than the traditional definition of "building work" found in the QBSA Act. The meaning of "construction work" and "related goods and services" encompasses a wide range of claimable items. Site clearing, site restoration, painting and decorative services, soil testing, cleaning of buildings, architectural services, consulting services and earthmoving works are just a few examples of the far reaching application of the Act. In Pioneer Sugar Mills Pty Ltd v United Group Infrastructure [2005] QSC 354, the parties entered into negotiations for additional works to be performed by the respondent. This variation, amongst others, expanded the scope of the work to be performed considerably. Justice Byrne held that a variation as such was not intended to be treated as a stand alone "construction contract" to which the statutory regime was to extend. Therefore it was held not to be "construction work" as defined in Section 10 of the Act.

Using licensed contractors

The QBSA regulates the building industry in Queensland to a system of licensing which controlled by the Queensland Building Services Authority.

Section 42 of the QBSA Act provides:

- A person must not carry out, or undertake to carry out, building work unless that person holds a contractor’s licence of the appropriate class under this Act.

- For the purposes of this section:

- Subject to subsection (4), a person who carries out building work in contravention of this section is not entitled to any monetary or other consideration for doing so.

- A person is not stopped under subsection (3) from claiming reasonable remuneration for carrying out building work, but only if the amount claimed:

- An unlicensed person who carries out, in the course of employment, building work for which that person’s employer holds a licence of the appropriate class under this Act does not contravene this section.

(a) a person carries out building work whether that person carries it out personally, or directly or indirectly causes it to be carried out; and

(b) a person is taken to carry out building work if that person provides advisory services, administration services, management services or supervisory services in relation to the building work; and

(c) a person undertakes to carry out building work if that person enters into a contract to carry it out or submits a tender or makes an offer to carry it out.

(a) is not more than the amount paid by the person in supplying materials and labour for carrying out the building work; and

(b) does not include allowance for any of the following:

(i) the supply of the person’s own labour;

(ii) the making of a profit by the person for carrying out the building work;

(iii) costs incurred by the person in supplying materials and labour if, in the circumstances, the costs were not reasonably incurred; and

(c) is not more than any amount agreed to, or purportedly agreed to, as the price for carrying out the building work; and

(d) does not include any amount paid by the person that may fairly be characterised as being, in substance, an amount paid for the person’s own direct or indirect benefit.

5A. An unlicensed person who, as a subcontractor, carries out, or undertakes to carry out, building work for a licensed trade contractor, does not contravene this section if the work is within the scope of the building work allowed by the class of licence held by the contractor.

It is also important to recognise that the licensing system is in theory designed to ensure some form of control over the financial stability of contractors by ensuring there minimum financial requirements met depending upon the type of work and the entity involved. It is also important to recognise that consequences may flow (which could be either positive or adverse) if an appropriately licensed contractor is not retain for the particular work in question. It could also turn out that an inappropriately licensed contractor is financially penalised by the impact of Section 42(3) which is designed to prevent unlicensed contractors from profiting thereby acting as a further disincentive for unlicensed contracting.

Being aware of builders’ standard forms

If your organisation is in the market to procure building work of some description then the building industry has available to it a number of benchmarks from which contracts can be negotiated. This assists to deliver some form of certainty of interpretation as well as provide a starting point in terms of risk allocation from which parties can negotiate.

The most common set of standard conditions available in the market place are those published by either Associations representing builders (such as the Master Builders Association or the Housing Industry Association) or that those published by organisations representing a crosssection of the industry (such as Standards Australia). It is common for builders who are comfortable produced by their own Association to attempt to have those adopted. Proprietors for whom building work is being performed must realise that there are a range of alternatives open and that the starting point really should be an assessment of risk in order that a decision can be made as to the most appropriate allocation which is therefore reflected in the standard conditions which may form the starting point of any negotiation to procure building work.

By way of example I set out some of the most typical construction delivery methods together with an analysis of some of the more common key issues, advantages and disadvantages.

(A) ‘Construct only’ contracts

A normal "construct only" delivery method involves the development of the design for a project by consultants retained by the Principal. Following this, a Contractor is engaged by the Principal (whether through a tender process or otherwise) to construct the project in accordance with the Principal’s design. This type of contract may be carried out on a lump sum or schedule of rates basis. Examples of standard "construct only" contract conditions include AS2124-1992, AS4000-1997 and the JCC series of contracts.

(B) Design and construct contracts

A design and construct methodology involves the preparation by the Principal of a "design brief", which outlines the key requirements of the project (ie. a description of the works, the performance requirements of the project and any outline design). A lump sum contract will be entered into with the selected Contractor, under which the Contractor will be responsible for designing the project on the basis of the design brief, and constructing the works in accordance with that design. A standard design and construction contract is AS4300-1995.

(C) Managing contractor, construction management and project management agreements

These methods of project delivery differ from design and construct in that the Contractor provides management services to the Principal, and the Principal contracts directly with trade contractors.

(D) Other problems with the ‘adversarial’ delivery methods

In a broader sense, there has been a trend in the construction industry for the party with the stronger bargaining power (usually the Principal) to shift the onus of responsibility of risk under a contract off themselves and onto the other parties to the contract. Such risk shifting is often undertaken without suitable compensation, and regardless of whether that party can influence or control the risk. This phenomenon, when combined with "fixed" or "lump sum" contract sums, causes the financial interests of the Principal and Contractor to become opposed from the start. Together with the introduction of onerous notification procedures, it can result in the parties adopting an adversarial approach to contract administration at an early stage of the project.

The need to bring projects on-line earlier, at a lower cost and pursuant to a more efficient "risk and reward" allocation system has driven the construction industry to develop new forms of delivery methods. A key element to these delivery methods is the concept of shared risk and reward.

Ensuring that your terms come out on top

The typical stages in contract formation and development are many and varied. The type of approach will often depend upon the nature of the transaction. Some of the more common scenarios which arise are as follows:

1. Battle of the forms It is common that one party will send a purchase order with terms and conditions and the other party in accepting the purchase order will send back its own terms and conditions. Each set of terms and conditions excludes the operation of the other. The question is which terms and conditions apply.

In general terms the purported acceptance on a different set of terms and conditions is not effected and will instead be a counter-offer. However, if further negotiations or acts of contractual performance take place, the last offer in time will usually succeed (although it will depend on the circumstances and the terms). Practically it is important to read and try and identify what terms and conditions apply with any offer and if they are unacceptable, send a letter or fax back saying that the terms and conditions do not apply.

2. Custom

Parties which are in a relationship for years and are entering into a great number of small contracts may find that the terms of their contracts evolve over time. Although the parties enter into a new contract on each occasion (e.g. individual purchase orders) the terms of that contract might be supplemented by the conduct of the parties in their course of dealings. What this means is that further terms may be implied.

It is always better to enter into a formal arrangement where the terms upon which a commercial relationship will be conducted is settled periodically. This may mean putting in place a standing offer for a period of time which should be a contract containing all of the relevant terms and conditions. The parties are then free by a simple mechanism to order goods or work pursuant to that standing offer, with certainty as to terms upon which they are doing it. A good example of this in the building industry is the way in which subcontract arrangements are put in place under standard terms and conditions published by the Master Builders Association.

3. Tenders

When a person lodges a tender that will comprise an offer to perform the obligations outlined in the tender documents. Typically that offer must remain open for the tender validity period and may be accepted by the person to whom the tender is made at any time during that period. This is certainly a very common form of procuring building work within the industry.

All that is required to accept a tender is notification which may often be made orally. Care should be taken when speaking to tenderers that they do not receive the impression that a tender has been accepted.

It is often the case that upon receipt of tenders a period of negotiation with one or more tenderers occurs. During this period, the terms of the tender are discussed, letters are exchanged and the terms of the tender changes. Each time that occurs, technically a new offer is made. It may turn out that it is not even clear if the original offer is still open for acceptance. This needs to be approached with care.

By way of example a letter purporting to accept an offer which in fact contains terms which are different to the offer does not constitute acceptance. Once again that could be construed as a counter-offer. In order for the contract to be entered into, the counter-offer must be accepted. There is of course the issue of performance as well because sometimes acceptance can occur by conduct, for example commencing work.

The Implications of the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 ("BCIPA")

Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004: Overview and recent trends

Object of the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act ("the Act")

The Act has now been in force in Queensland for more than two (2) years. Implemented to improve payment in the Building and Construction Industry, the Act is a useful tool for workers to recover payment for outstanding claims.

The Act’s principal objective is to ensure that if a person undertakes construction work under a construction contract or supplies related goods and services under a construction contract, that person is able to receive and recover progress payments.

What this means is that workers in the construction industry who otherwise might encounter difficulties in obtaining payment for work performed, might be entitled to enliven the rapid payment and subsequent adjudication process contemplated by the Act.

What can be claimed?

A person entitled to receive progress payments for "construction work" and "related goods and services" performed under a construction contract is entitled to submit a statutory payment claim setting out the amount that the claimant says is due and owing.

"Construction work" is defined broadly (broader than the traditional definition of "building work" contained in the Queensland Building Services Authority Act 1991) and includes amongst other things, site clearing, site restoration, painting and decorative services, testing of soils and cleaning of buildings, structures and works.

Similarly, the meaning of "related goods and services" comprises a wide range of claimable items including:

(a) The supply of goods which comprise building materials and components arising from construction work and plant and equipment (whether supplied for sale, hire or otherwise) for use in connection with the carrying out of construction work; and

(b) The supply of services which comprise labour supply, architectural, design, surveying and quantity surveying, engineering, interior and exterior decoration, landscape services and soil testing services relating to construction work

There are some restrictions as to the types contracts to which the Act applies (for example, the Act does not apply to contracts for domestic building work). However, regardless of these restrictions the Act encompasses a wide range of contracts that were traditionally not thought to be construction contracts. Architectural services, consulting services, earthmoving works to name are few are examples of types of "construction work" or "related goods and services" where claimants have successfully recovered progress payments under the Act.

The wide reaching application of the Act is reinforced by the anti-avoidance provision in the Act that prohibits contracting out. In other words, any provision of a contract which is contrary to the Act is void.

Recovery procedure

In brief, a claimant wishing to enliven the provisions of the Act must follow the time frames and processes set out in the Act by issuing a statutory payment claim.

A respondent that receives a payment claim should take immediate action and either pay the amount due or issue a payment schedule setting out the amount (if any) the respondent proposes to pay or setting out the reasons why the respondent says the claimant is not entitled to payment.

Failure to respond to a payment claim by not submitting a payment schedule within the time frames required by the Act is fatal to a respondent’s case. If this occurs, a claimant may then proceed to recover the amount of the payment claim by way of summary judgment in any court of competent jurisdiction, and a respondent is not entitled to raise any defence to the action.

Alternatively, a claimant can follow the procedures in the Act to proceed to adjudication if a payment schedule is not received or if a payment schedule is received that a claimant is not satisfied with.

In summary, from a claimant’s point of view, we recommend that a claimant seek legal advice to ensure that their payment claims are valid in terms of the Act and that a claimant is aware of critical time frames to enforce their claim. Likewise, from a respondent’s point of view, a respondent should be able to recognise when they have been served with a payment claim and take appropriate steps within the time frames provided by the Act to defend their position (in the event that payment is not forthcoming and the respondent disputes the amount claimed).

Recent statistics

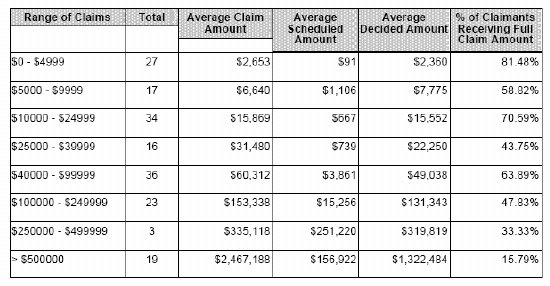

At the close of 2006, the Building and Construction Agency (the agency established under the Act to assist the Adjudication Registry) published statistics in its December report which summarises the year in review for adjudications. Bear in mind that these statistics relate to those matters which proceeded to adjudication and do not reflect the amount of payments made as a result of payment claims which did not result in adjudication.

Decided Matter Statistics

The above table demonstrates that of 175 adjudication decisions released in 2006, claimants appear to be receiving favourable decisions. In adjudications involving a large quantum in dispute the claimant’s success rate is significantly lower (claims in excess of $250,000). However, this is not to say that claimants in the larger claim bracket did not receive at least a partial success rate with respect to their claims as the above table only demonstrates the percentage of claimants receiving the full claimed amount.

Adjudicator’s fees

Pursuant to the Act, a claimant and respondent are liable to pay the adjudicator’s fees in equal proportions, or in the proportions determined by the adjudicator. Typically, the unsuccessful party will be liable to pay the adjudicator’s fees and as the above table demonstrates, where the payment of total fees has been awarded, the respondent has in most cases (75.6%) been required to pay the adjudicator’s fees.

Challenging an adjudicator’s decision: Judicial review

At present, the Act is subject to the Judicial Review Act 1991 ("the JR Act"). There are however, moves in the construction industry to close the avenue of review under the JR Act in order to uphold the interim nature of adjudication decisions.

Until parliament legislates to close the avenue of review under the JR Act, aggrieved recipients of adjudication decisions may apply for a review provided that the application is made pursuant to the grounds of review set out in the JR Act. The leading authority on judicial review in Queensland as it relates to the Act is the 2005 case of JJ McDonald & Sons Engineering Pty Ltd v. Neil Gall & Ors1. Dutney J held that the adjudication decision in that case was made under an enactment and properly subject to judicial review.

At least for the present, judicial review remains a mechanism for aggrieved persons wishing to challenge an adjudication decision.

Footnotes

1 [2005] QSC 305

Australia's Best Value Professional Services Firm - 2005 and 2006 BRW-St.George Client Choice Awards

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.