ABSTRACT

The Australian construction industry is suffering from low and declining profits; caused in large part by the misallocation of risk and a misunderstanding of the forces driving further efficiencies and productivity. Whilst the minor ‘pain’ of low profits is borne primarily by the contractors, many clients are finding it impossible to escape the consequences of major problems such as their D&C contractor becoming insolvent, intractable or intransigent. Many of these clients are finding themselves under resourced to manage these major problems when they arise. This paper identifies some of the structures and assumptions creating risk within construction projects and suggests a strategy to better align risk and reward.

Many clients select a ‘fixed price, D&C’ contract for their project based on the premise this is ‘low risk’; we argue in fact this approach may place all of the clients ‘eggs in the one basket’. The client surrenders, at least in part, control of the design of its building to a contractor who has a ‘horizon of interest’ extending one or two years into the future (not the 50 years the asset will be used). The contractor accepts an inherent conflict of interest between optimising the design for the client and minimising costs to keep the contract financially viable; and has access to tools such as the ‘Security of Payments’ legislation to help rectify cash flow problems if it finds itself losing money. The role of consultants in the design process is often marginalised and loyalties of novated consultants confused and dislocated.

The efficient management of risk requires contractors and clients to work together to deliver the right project for the right price. The legal/contractual framework to support this innovation requires careful sculpting for each project. It involves utilising modern forms of contract such as ‘partnering’ and ‘alliance contracts’, and needs the full spectrum of risks and requirements to be analysed and balanced in an effective and efficient way.

This paper will outline some fundamental pre-conditions to the development of efficient risk balanced contracts that encourage effective relationships and efficient project delivery.

1.0 OVERVIEW OF THE AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRY

1.1 STRUCTURE OF THE INDUSTRY

All levels of the Australian construction industry are suffering declining profits (Weaver and Hyde 2005) –

- The major contractors dominate the market and industry as a whole, but the number of entities is shrinking through failures (eg, Walter Construction Group) and acquisitions.

- The medium sized businesses are squeezed between the low cost small contractors and the generally well financed (if not economically profitable) majors.

- The small end of the industry is the home of most subcontractors and niche/home builders. The sector is noticeable for its very low entry threshold, allowing under resourced and novice businesses to start easily; and its correspondingly high failure rate. The resultant skill and technology loss to the industry is significant and a barrier to industry success and growth.

1.2 PROFIT TRENDS

The reward available to the various contractors and suppliers is the profit they make from the works they perform. As can be seen from Fig. 2, the level of profitability in the industry is low and declining.

Figure 1 - Low Profit Margins - Selected Contractors & Average

(Clayton Utz and Australian Constructors Association 2005)

In the past, the traditionally low profitability of the industry was off set by a relatively high turnover on capital and the ability of head contractors to harvest the benefit of managing cash flows; generally by claiming early and deferring payments to suppliers and subcontractors. In the past, this meant a well managed business was largely funded by the cash flow derived from its projects and a net profit margin of 2% could be multiplied by a factor of two or three based on turning over the entire capital base of the business several times in a year.

Both of these elements are under threat. An internal survey by Westpac Bank (Hyde 2005) shows the rate of turnover of assets across all major industry players has been steadily declining, and in 2003/2004 was averaging less than 1.5. Whilst the introduction of the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Acts in various states enables subcontractors and suppliers to enforce their rights to timely and regular payments (Doyle 2004).

1.3 INDUSTRY RISKS

The Australian construction industry has a number of characteristics that increase both development and construction risks. Some are endemic such as the industrial relations climate and multiple layers of government. Others, particularly the ‘Building and Construction Industry Security of Payments’ legislation and the rapid escalation in material prices are new and the industry is still attempting to come to grips with the consequences of the change. Others are structural market size and volatility, information technology and innovation requiring critical mass and rewarding scale, governmental policy preference for single provider on major deliverables and labour market realities. Two of the key risks impacting every building project are:

1.3.1 Industry Capacity

The Australian building industry has been struggling to meet a rapidly escalating demand in many key areas (see Fig. 2); although a recent report by Master Builders Australia (Master Builders Australia 2005) based on a survey of its members shows current industry conditions flattening out in the June 2005 quarter and suggests a easing may be starting to appear.

Figure 2 - Construction Workload AU$

(Clayton Utz and Australian Constructors Association 2005)

The current building boom (with workloads close to the 2004 peak) has led to price escalation and the de-skilling of the overall workforce as contractors employ aggressively seek to fill vacancies and encounter delays as suppliers and subcontractors experience the same over-demand as the main contractors.

This shortage of skilled workers and lack of overall industry capacity has led to the average annual trade price inflation exceeding 6% pa over the last three years (to 2005) and trade price inflation is expected to continue to average 5% for the next two years (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu 2005). Very few contractors on ‘fixed price’ bids would have allowed for these rates of inflation (and still had the lowest tender price).

1.3.2 Building Industry Security of Payment Legislation

The Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment (BCISOP) legislation in force in most States has been accurately described as enforcing a "pay now, argue later" regime onto the construction industry. Claims made under the relevant Acts are typically resolved within 4 to 6 weeks and Adjudicated payments are generally enforceable within seven days. Whilst any Adjudicated amount is considered a ‘payment on account’ (similar to a normal progress payment) the impact on cash flows for the organisation that is required to pay can be significant with a number of awards exceeding $1 million (NSW Government Construction Agency Coordination Committee 2005).

The Acts are "causing a radical re-think of many traditional project management and contract management processes. All professional contract administrators must manage every aspect of a contract on the assumption that all outstanding issues will be included in a claim under the Act in the next month. It is no longer acceptable to let claims remain unanswered" (Doyle 2005).

1.4 THE COST OF FAILURE

More frequently one sees new headlines announcing profit downgrades for one major contractor or another, this trend is likely to be as damaging to the clients of the Australian construction industry as it is to the shareholders in the businesses featuring in the announcements. Despite many attempts to draft ‘watertight’ contracts, no contract can protect a client from the failure of a contractor or protect it from the cost of defending claims made by a contractor; some part of the ultimate risk is always the clients! This is the actual experience of clients of the Walter Construction Group, Henry Walker Eltin, and others.

Where the contractor remains viable but knows it is losing money, the client is potentially subject to a range of claims, either genuine or fabricated. Even if the client is ‘successful’ in defending a claim it is unlikely to recover the full extent of costs internal, external tangible and intangible involved in managing the dispute. Negotiated settlements frequently involve reduction in scope, quality or other facets of the project as well as financial settlements and ongoing impacts on core business objectives.

Figure 3 - © The Age Sat 9th July 2005 (Front Page)

The Victorian government and the Spencer Street station developers agreed to settle their disputes in mid 2005 but with numerous reductions in scope and design changes including reducing the area covered by the ‘wave roof’, deleting a major new pedestrian link and using lower cost finishes on the platforms.

Where a negotiated settlement is not possible; the natural reaction of any business facing a significant loss is to attempt to cut its costs by downgrading on-site supervision, reduction in quality and/or the slowing of the construction process.

The consequence of all of these potential outcomes ultimately impacts the building industry’s clients. They pay more and receive less than they expected! Changing this outcome is a key ingredient in the future growth of the industry. When the construction industry is perceived by its clients to deliver quality and value, the potential market for its services will increase as clients choose to invest discretionary expenditure in Australian construction projects.

2.0 THE RISKS IN FIXED PRICE D&C CONTRACTS

One of the more disturbing trends in the Australian construction industry has been the tendency for clients to attempt to transfer all of the project risk to the contractor. This approach is most obvious in the increasing common application of Design and Construct (D&C) Contracts. D&C contracts place a significant portion of the development risk onto the contractor but in many cases, the contractor’s margin remains the same as for a traditional tender. While this form of contract can be effective when correctly applied, overuse leads to confusion, lack of clear risk allocation and disputes.

2.1 D&C CONTRACTS – THE CLIENT’S PERSPECTIVE

The use of Design and Construct contracts grew out of the ‘supply side’ building boom of the 1980s and is superficially attractive to clients, often as a way of reducing design costs and delays. Projects were built to on-sell and quality was focused on short term needs. The current ‘demand side’ boom is ‘build to own’ – the overall contracting process should now be focused on quality, whole of life costing, and a long term view of value.

The likely consequence of using the combination of an overstretched principal’s team and a ‘D&C’ construction contract with a low ‘fixed price’ include:-

- Accepting low cost design in preference to a quality design. The contractor will have pushed the design costs as low as possible to minimise its overall cost and as a consequence, the designers will not have the time or budget to undertake proper design consultations and reviews with the client to produce an optimum design.

- Loss of client control over the design; as long as the final design meets the D&C brief, the contractor will have met its obligations. Writing a ‘perfect’ design brief is virtually impossible, therefore every interpretation will be heavily biased by the need of the contractor’s designer’s, and the contractor, to save costs rather than the best long term outcomes for the client.

- D&C provides a so-called ‘single point of responsibility’. If the project is a major failure the client can theoretically sue the contractor, or the contractor’s insurers. However, construction clients cannot mitigate ultimate risk (ie, the liquidation of head contractor) and increase their exposure to damage by attempting to avoid all risk. Without proper management strategies to monitor and respond to issues before they become project critical, the client may end up with no effective and commercial rights to the design work done by the contractor (particularly if designers have to be changed) and will inevitably face major cost escalation and time delays in attempting to complete a building after the contractor has gone into liquidation.

- By accepting an unrealistic price, clients are inviting longer term expenses. Contractors forced into a loss will almost inevitably seek to recover monies by making claims; this is now much quicker and easier for the contractors with the advent of the various ‘Security of Payment’ Acts. The other natural reaction from a contractor losing money on a contract is to attempt to cut costs. Typically this involves reducing supervision with an inevitable impact on quality and may also involve overt reductions in the quality of materials and workmanship. The costs incurred by a client in closely supervising a contractor’s work to enforce quality, defending claims and seeking to recover loses and disputed Adjudication payments can quickly erode any initial gains achieved by accepting an unrealistically low price.

The quality movement in manufacturing led by people such as Deming (Deming 1982) and Crosby (Crosby 1969) have long stated quality should be designed in, not inspected in. This philosophy is equally true for construction. Construction industry clients need to question the wisdom of abandoning control and influence over the design process for ‘their project’ to the lowest cost contractor/designer. More collaborative models for the D&C track can be used to produce a more satisfactory result.

2.2 D&C CONTRACTS – THE CONTRACTOR’S PERSPECTIVE

D&C contracts transfer substantial risk to the contractor as well as responsibility.

In the first instance, the D&C contractor has a massive conflict of interest to resolve. On one hand there are its obligations to its shareholders, employees and subcontractors to generate profits and remain viable so it can pay wages and debts. This set of obligations requires the D&C contractor to seek cheapest possible solution to its contract obligations so as to maximise its profits (or minimise losses). This is diametrically opposite to the normal obligations of a designer which typically involve seeking to achieve the optimum design solution for the client by taking the time to balance multiple considerations including quality, whole of life costing, budgets, aesthetics and design costs.

The next major risk accepted by the D&C contractor is the interpretation of the design brief (and/or accepting the novation of the client’s nominated designer). Any apparent ambiguity in the brief will tend to be read ‘down’ by the contractor and ‘up’ by the client. If the client wins the argument, the D&C contractor can end up building a much more expensive project than it allowed in its tender. This risk is compounded if the contract is a ‘fixed price’, awarded to the lowest bidder!

Beyond the issues surrounding the D&C process discussed above, the D&C contractor also accepts the full spectrum of design and development cost risks. The design solution may simply cost more to build than initially estimated! Traditional development margins were in the order of 30% to allow for the escalation of costs as the design evolved. In D&C contracts, many contractors are accepting these development risks at traditional contracting margins – we suggest this is a recipe for disaster.

The industry needs a better way to apportion risk, responsibility and profits.

3.0 DEVELOPING INTEGRATED CONSTRUCTION TEAMS

The problems and risks outlined above are not unique to Australia; the UK building industry has experienced similar problems over a significant number of years. The key difference is both the industry and its clients, with the active support of government, have been working to resolve the issues.

Reports by Latham (Latham 1994) and Egan (Eagan 1998) have led to the formation of Constructing Excellence1 (aimed at achieving a step change in construction productivity by tackling the market failures in the sector) and the publication of numerous studies, reports and recommendations. Other initiatives include the ‘Delay and Disruption Protocol’ (The Society of Construction Law 2002) which focuses on the management of schedules and time related disputes.

The conclusion from these reports, supported by numerous case studies and surveys is that a cooperative approach to construction delivers real benefits to all of the parties (M4I 2000; M4I 2002; M4I 2003). The Latham report indicates partnering as a way forward to improve efficiency and profitability. Egan expanded on this concept to recommend integrated supply teams and long term client / construction team relationships to allow lessons learned to be incorporated into the next project.

The survey data available from the Constructing Excellence web site shows an engaged client and successful teaming can deliver a better building at a lower cost, in less time than traditional contracting and the builders make more money!

These lessons have not been entirely ignored by the Australian construction industry; a significant number of major projects have been successfully delivered using partnering and alliance contracts and have largely delivered on the promise of better buildings at reduced costs. Eagan’s ideas of long term relationships between supply teams and clients also seem to be taking hold in a number of maintenance and support areas.

However, the models in use at the moment are expensive to implement focusing on bespoke contracts, management and team ‘retreats’, focussed team building exercises and the like. Whilst this level of investment in team creation is justified for large $100 million+ contracts (where the cost of failure could be enormous and the benefits of success equally great) it is not practical or necessary on small to medium sized contracts.

The balance of this paper will address the requirements for a contracting model that implements the lessons of Latham and Egan in a cost effective, pragmatic way designed for contracts of just a few million dollars value.

3.1 TEAM FORMATION

The key element within the ideas of Latham and Egan, as well as the proponents of partnering and alliance contracts is the need to develop a strong team consisting of the client, head contractor, designers and key subcontractors/suppliers. Significant effort is poured into team creation in the expectation that a strong team will evolve, committed to the common cause of delivering a ‘great’ project that meets all of the different party’s expectations. This is one key area where the needs (and budget) of a major project differ significantly from smaller projects.

3.1.1 Competing theories of team development – Tuckman

The ‘traditional’ approach to developing teams adopted by most partnering agreements appears to be based on the theories of Tuckman (Tuckman 1965; Tuckman and Jensen 1977). The assumptions are that teams are groups of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose and hold themselves mutually accountable for its achievement. Ideally, they develop a distinct identity and work together in a co-ordinated and mutually supportive way to achieve their agreed goals. Successful teams are characterised by a team spirit based around trust, mutual respect and helpfulness. This usually requires co-location, and help to move through the ‘forming, storming and norming’ phases of development to achieve the ultimate aim of a ‘performing’ team.

Figure 5 – Team Formation, Tuckman Model (Tuckman 1965)

The underlaying assumption in the Tuckman model is that the creation of a committed, performing team is a steady progress through various stages of development and the commitment of time and effort; together with critical physical supports (eg, co-location) and psychological supports (eg, the overt support of senior management from all parties) will achieve the desired results. Experience suggests this model is both realistic and achievable provided the necessary environment is created and adequate and continuing investments made.

Whilst being an appropriate model for large projects with relatively stable teams, the problems with this approach on smaller projects include:

- The project is rarely big enough to warrant a fully co-located team, many ‘small project’ team members will be part time working from their own office.

- The trust and co-location aspects of large project teams allow the assumption that the team will largely resolve problems internally, with dispute escalation occurring at a relatively late stage – on smaller projects support systems need to be in place to generate trust and resolve disagreements much sooner.

- Large project teams seek to involve a wide range of parties in the team (it is both necessary and desirable), the commitment of many parties on a smaller project is often too limited to warrant much effort in engaging them in a ‘team’.

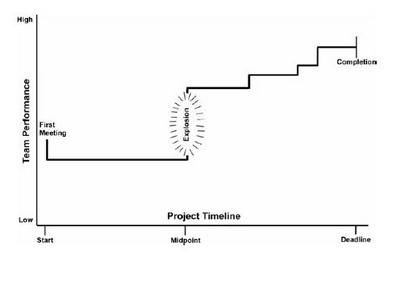

3.1.2 Competing theories of team development – Gersick, Punctuated Equilibrium

Gersick’s (Gersick 1988) concept of ‘punctuated equilibrium’ proposes that team formation is not characterised by gradual change, rather it is punctuated by ‘cataclysmic events’ that force movement to the next evolutionary level. According to Gersick, the team will quickly develop a set of operating principles which are sufficient, but less than optimal, in the early stages of a project where there is a normally a great deal of good will. It takes a ‘trigger event’ to move the team out of this level of operation. This trigger can be dissatisfaction with project progress, interpersonal conflict or any one of the usual project flashpoints of scope, time, cost and quality.

This trigger is the catalyst for revision of team relationships, either consolidating the team values and contributing to higher team performance (if the result is positive). Or, if the results are negative the team could be forced to disband or have its membership modified; it is almost impossible to revert to the pre-cataclysm mode of operation after one of these triggers.

Figure 6 - Punctuated equilibrium model of team formation - (Gersick 1988)

In the context of ‘punctuated equilibrium’ project managers need to operate differently. At the start of a small construction project, there is little time to build a trusting relationship between the various members of the team. They must work out their differences on the fly and blindly trust one another to do their jobs. ‘Swift Trust’ (Meyerson, Weick et al. 1996) does not just happen; there are factors in the environment which are preconditions that enable and encourage trust to be given and used well. Some of these are:

- Linked overall goals, rewards and penalties. By putting people in the same boat they are forced to develop a system of common trust.

- Interdependence. Where people are independent, less trust is needed. However, if some are more dependent than others, then power positions are created with a much less trusting environment.

- Just-enough resources. There should be sufficient resources to do the job, otherwise battles for resource will erode trust. The ability to increase resources quickly, line with project requirements, is also necessary.

- Professional role focus. A focus on acting as, and treating others as, professionals leads to trust in their professional capabilities.

Combining these two theories creates a framework within which performing teams can be developed for smaller projects without the need to expend the significant time and effort involved (and warranted) in developing teams for major projects.

The key components of the framework are:-

- The project client (with the assistance of the consultants and head contractor) creates an environment encouraging the formation of ‘Swift Trust’ and clear purpose and timing.

- The people involved in the core team are kept to a practical minimum.

- Support systems are put in place before the project starts to deal with the inevitable ‘explosion’ with the overt aim of lifting team performance to a higher level.

- Systems are in place to induct new people to the team as the project progresses. However, the invitation is to join the team ‘as is’ and contribute rather than join a process to develop a new team.

4.0 A RECOMMENDED FORM OF CONTRACT

4.1 CLIENT ENGAGEMENT

The key starting point for a successful smaller project alliance is the willingness of the client to be fully engaged in the delivery of its project and consistently focussing on getting the optimum project for the optimum price. If the client focuses on costs rather than outcomes there is little point in engaging in anything other than a traditional fixed price D&C contract (with the usual round of challenges, claims, disputes and litigation).

Unfortunately, the fallacy of a firm fixed price contract remains in many people’s minds despite centuries of experience to the contrary (Weaver and Hyde 2005). With current margins below 2%, if builders are locked into a ‘fixed price’, they can be expected to claim for every change (real or imagined) and they have the ‘Security of Payment’ legislation to help. Change is inevitable; no client can expect to specify every facet of its requirements and the contracting process should recognise this reality and focus on creating value. Similarly, attempts to artificially avoid risk will often generate sub-optimal outcomes. Clients need to be aware of the risks inherent in their project and seek to fund and manage the project realistically.

Enlightened clients, seeking better outcomes must take the lead in balancing risk, cost and control. Risk should be borne by the party most capable of managing it. Control, particularly over design and quality should be retained by the client to a larger extent, particularly if the client plans to own the project for many years after the contract is finished. Costs and schedules need to be realistic and achievable.

4.2 CONTRACT FORMATION – CLIENT DRIVEN PROJECTS (CDP)

The construction contract required for a CDP needs to be drafted in a way that defines the work to be done and facilitates pragmatic alliancing. Key elements of the contract should include:-

- Only participants that are significantly important to the project should be involved in teaming.

- The teaming process should be designed to facilitate the movement of people into and out of the team as their importance to the project changes over time.

- Team inductions focus on supporting the established culture of the team.

- The pricing model needs to be based on effective pricing theory and designed to drive the performance most beneficial to the client.

- Full information as to commercial performance of all significant players needs to be openly available and used as a team asset.

- The project needs a facilitator, separate from both the contractor and the principal, to direct project important initiatives, lead the team formation process and facilitate negotiations to resolve disputes.

- Detailed records need to be kept of the resources used on the project and the status of work. The model clause at Appendix C of the UK ‘Delay and Disruption Protocol’ is a useful guide.

- The project should be ‘open book’. Facilities need to be in place to allow the full visibility and exchange of all project related information between the parties (a number of web based portal systems are readily available to facilitate this process).

- Independent experts need to be in place to monitor and facilitate agreement on all matters relating to cost and time.

- Probity planning and audits should be designed into the system to build and verify trust.

- An effective ‘Total Quality Management’ (TQM) approach should be embedded in the head contract and subcontract agreements and become an intrinsic part of the team’s philosophy.

4.3 CONTRACT STRUCTURE

The underlaying philosophy in this proposed model is based on pragmatism. It is far easier to build trust and generate a performing team if there are systems in pace to facilitate visibility and accountability.

The ‘facilitator’ is paid by the alliance to lead team development and facilitate the resolution of problems, a person skilled in negotiation and mediation appointed before problems arise (and involved in creating the team) should be in a position to facilitate the resolution of most issues, particularly if all of the necessary information is freely available.

The independent cost and time ‘auditors’ are engaged by the alliance to oversight the project team’s discussions in these areas (not to do the work). The presence of a respected ‘expert’ with full access to all of the relevant data should mean that any disagreements between the parties are focused on principals and facts, not perceptions.

The contract itself will cause contractors who are not interested in alliances to selfselect out and to select only those who are comfortable in such an environment. Properly drafted, the contract will ensure the parties are aware of their commitments to open honest communication and the built in requirements for probity audits and reviews will encourage honesty.

The costs associated with the independent reviewers should not be particularly high if their involvement is proportional to the value and complexity of the project. The work they will be required to perform is limited and will be facilitated by the open access to all of the project’s information.

5.0 CONCLUSION

Alliance and partnering have been proven to be successful forms of contract both in the UK and Australia. However, the costs under existing models associated with developing ‘performing teams’ are high, tend to require collocation and are best suited to very large projects.

Smaller projects need a different, more pragmatic approach to the development of partnerships or alliances focussing on the use of efficient communication systems (to create visibility) and independent experts (or referees) to encourage open and effective communications and help resolve disagreements early, before the disagreement can escalate into a disrupting dispute.

The contract model discussed in this paper outlines the basic framework for such a contract and offers a new way to deliver value to the construction industries clients whilst restoring a level of profitability to businesses in the industry.

References

Clayton Utz and Australian Constructors Association (2005). Special Report June 2005: Succeeding in a Fraught Construction Market. ClaytonUtz. Sydney: 10.

Crosby, P. B. (1969). Quality is Free. New York, McGraw-Hill Inc.

Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (2005). Property & Construction presentation, March 2005, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

Deming, W. E. (1982). Out of the Crisis. Melbourne, Australia, Cambridge University Press.

Doyle, J. (2004). Adjudication Pressurises Project Administration. PMOz, Melbourne.

Doyle, J. (2005). SoP; A new answer to an old question. RICS. Melbourne.

Eagan, J. (1998). Rethinking Construction.

Gersick, C. (1988). "Time and Transition in Work Teams: Towards a new Model of Group Development." Academy of Management Journal 31: 9 - 41.

Hyde, R. (2005). Westpac Banking Corporation - Construction risk issues., Westpac: 10.

Latham, M. (1994). Constructing the Team: Final Report of the Government/Industry Review of Procurement and Contractual Arrangements in the UK Construction Industry. London, HMSO.

M4I (2000). 65% Cut in Rail Embankment Stabilisation costs. Rethinking Construction. Movement for Innovation. London, Constructing Excellence: 2.

M4I (2002). ASDA Store - 30% Gain. Rethinking Construction. Movement for Innovation. London, Constructing Excellence: 2.

M4I (2003). Major Heating Contracts. Rethinking Construction. M. f. Innovation. London, Constructing Excellence: 2.

Master Builders Australia (2005). National Survey of Building and Construction, June 2005. Canberra, Master Builders Australia: 8.

Meyerson, D., K. E. Weick, et al. (1996). Swift trust and temporary groups. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. R. M. Kramer and T. R. Tyler. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage: 166 - 195.

NSW Government Construction Agency Coordination Committee. (2005). "Security of Payment - Adjudication Progress Reports." Retrieved 20/10/2005, from http://www.construction.nsw.gov.au/

The Society of Construction Law (2002). Delay And Disruption Protocol. London, The Society of Construction Law.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). "Developmental sequence in small groups." Psychological Bulletin 63(6): 384-399.

Tuckman, B. W. and M. A. C. Jensen (1977). "Stages of small group development revisited." Group and Organisational Studies 2(4): 419-427.

Weaver, P. and R. Hyde (2005). Construction - A Risky Business. International Construction Conference 2005, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Footnotes

1. See http://www.constructingexcellence.org.uk/

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.