- with readers working within the Environment & Waste Management industries

- within Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration and Law Department Performance topic(s)

Corporate carve-outs are poised to dominate the Australian private equity market in 2024, presenting significant opportunities for investors. A carve-out occurs when a company divests a portion of its business, generally spinning off a separate entity or group. This strategy allows the parent company to focus on its core operations while unlocking value from non-core assets. By understanding and proactively addressing the potential tax implications of carve-outs, private equity funds can navigate this growing trend in the market and unlock value for their investors. It is advisable for funds to work closely with tax advisors and experts to ensure compliance and optimise tax outcomes throughout the carve-out process.

Generally, carve-outs consist of a divestment by a corporate group of either shares in certain subsidiaries or assets in a business unit or a combination of both. The specific tax outcomes which could arise depends on whether it would be a share or asset sale.

Below are some key tax implications to consider when contemplating undertaking a carve-out transaction.

Income Tax Implications

Share divestment – vendor implications

The corporate carve-out of a subsidiary of an Australian entity should generally result in a capital gains tax ("CGT") event for the vendor. A taxable gain equal to the difference between historic tax cost base and sale proceeds less transaction costs multiplied by the corporate tax rate (whether it be 30 percent for most corporate groups or a lower 25 percent for some smaller entities) should arise for the vendor, typically with no CGT discount available.

Where the vendor is a tax consolidated group, certain tax calculations will need to be undertaken to confirm the tax cost basis of the exiting entity. Broadly, these calculations are performed by deducting the exiting entities' accounting liabilities from the tax cost base of assets held by the exiting entity. Where this outcome is negative, then a capital gain equal to this negative amount could arise. As such, any corporate carve-out from a tax consolidated group will need to be carefully managed to minimise any additional tax leakage which could arise on an exit.

Share divestment – buyer implications

A.) Vendor is a standalone taxpayer

Where the vendor is a standalone taxpayer (i.e. not a tax consolidated group), then the exit tax implications are relatively straightforward. The purchase price plus any incidental costs would just form part of the tax cost base of the acquired entity.

B.) Vendor is a tax consolidated group

However, where the vendor is a tax consolidated group divesting of a wholly owned subsidiary member, then additional tax complexities could arise.

Broadly, under the tax consolidation rules, the head company of a tax consolidated group is responsible for the tax filing and obligations of every member of the group. Should the head company default on its income tax payment obligations, then each subsidiary for the period to which the liability relates would be jointly and severally liable for this unpaid income tax debt.

The only way for an exiting entity to sever this joint and several liability would be to ensure that:

- A valid tax sharing agreement ("TSA") exists; and

- A 'clear exit' payment is made by the exiting entity.

Thus, it is critical for a purchaser to ensure that the acquired entity meets both of the above requirements otherwise it could potentially inherit the income tax liabilities of the entire vendor group (which it should not economically be liable for).

In particular, this risk could be heightened where there is a live tax authority review or audit which could seek to amend historic tax positions of the group.

Where the abovementioned is not possible (for example, where there is no TSA or where clear exit was not obtained), then a number of factors could mitigate (but not totally remove) this historic tax risk including:

- Confirming that the vendor tax group has substantial tax loss carryforward (which is capable of being utilised) that could shelter any adverse tax adjustments made by a revenue authority;

- Usage of a warranty and indemnity insurance policy in a transaction context which could shift this risk to an insurer; or

- An alternative transaction structure such as an asset sale where tax liabilities cannot be adopted.

It must be noted that the benefit of obtaining contractual protection from the vendor group may be of limited protection as it does not protect against the overall commercial and creditworthiness risk of the vendor group in defaulting on any historic tax liabilities that could arise from a revenue authority audit or review (i.e. the counterparty risk of the vendor defaulting on the income tax liability still exists regardless).

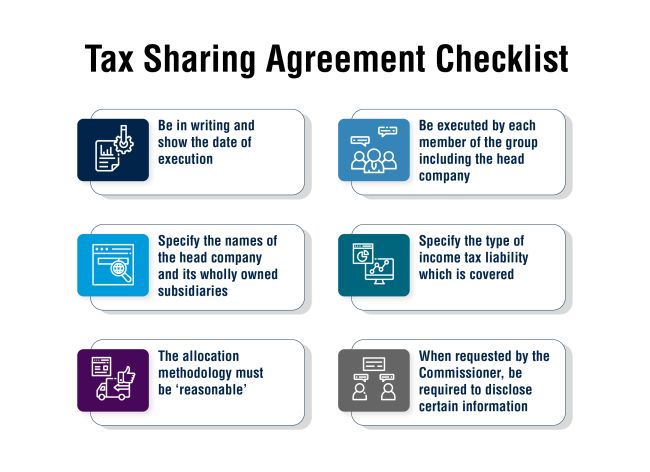

1. Tax sharing agreement

A tax sharing agreement is an agreement between the members of a tax group to contractually allocate the group tax liability amongst themselves. A TSA must be 'valid' under the Australian tax rules to be able to cover historic tax liabilities. In order for it to be 'valid', the following factors will need to be satisfied:

2. Clear exit

Where a valid TSA is entered, then exiting subsidiaries can sever historic joint and several liability and limit any historic liabilities to the amount calculated under allocation methodology under the TSA if a 'clear exit' is obtained.

The clear exit procedures are usually found in the terms of relevant governing TSA but in most cases, it is achieved through the leaving entity making a clear exit payment to the head company. The clear exit payment is calculated according to the terms of the TSA but typically is equal to a reasonable estimate of the allocation of the group tax liability. Where the vendor group is in tax losses, then the clear exit payment could be $1 (representing the payment of a nominal amount). It is critical to document this payment in any case as it evidences the severing of historic joint and several tax liabilities.

Once an entity has made a 'clear exit', then the Australian Taxation Office should not pursue the divested subsidiary for any group debt of the vendor group.

Asset sales

While less commonly utilised than a share acquisition, an asset purchase has fairly simple Australian income tax implications, although may give rise to additional stamp duty obligations. Generally, a CGT event should be triggered by the vendor. A taxable gain equal to the difference between historic tax cost base and sale proceeds less transaction costs multiplied by the corporate tax rate (whether it be 30 percent for most corporate groups or a lower 25 percent for some smaller entities) should arise for the vendor.

Pre-completion restructures – asset and share transfers

Where assets or shares need to be internally transferred within a tax consolidated group, these transactions are generally ignored from an income tax perspective. However, stamp duty implications may arise which are further discussed below in this article.

Where the assets or shares are internally transferred between a group (which is not consolidated for tax purposes), then this may trigger a CGT event for the selling entity. Professional tax advice should be taken in such circumstances to properly structure any pre-completion restructures.

Stamp Duty Implications

Corporate carve-outs will often involve the restructuring of assets and entities into a specific vehicle whilst on occasions this can include the direct transfer of existing entities, divisions or businesses. There will likely be Australian stamp duty issues to manage whatever the final steps are for the carve-out.

Stamp Duty Basics

Stamp duty is a state-based tax that is imposed on dutiable transactions involving dutiable property. Dutiable transactions include, amongst other things, agreements to transfer and transfers of dutiable property as well as declarations of trust over dutiable property. Dutiable property varies in each Australian jurisdiction and will include land and other tangible assets (plant and equipment) as well as goodwill and intellectual property in Western Australia (WA) and Queensland (QLD).

The rate of stamp duty varies but can be up to 6.5 percent on the greater of unencumbered (market) value or consideration payable (inclusive of GST, if any, and assumed liabilities). There is also additional foreign purchaser surcharge duty (up to eight percent) payable on the acquisition of residential land in some jurisdictions.

The liability for stamp duty falls on the purchaser although the liability falls on the parties to the transaction in QLD.

Landholder Duty

There are broad landholder duty provisions which tax the transfers of the securities (shares or units) of a company or unit trust as if there was a dealing in the underlying land type assets. What constitutes land for the landholder duty provisions includes freehold land, fixtures, interests in land (such as leases and leasehold improvements) as well as tangible assets that are physically annexed to the site of the interest in land. In broad terms, these provisions trigger duty where a person acquires either 20 percent more (such as New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria (VIC) for unit trusts) or 50 percent or more (such as NSW and VIC for companies and WA and QLD) interest in a landholder entity taking into account broad aggregation rules for associated/related persons or under "one arrangement".

The liability for landholder duty falls on the purchaser although some states also impose landholder duty on the landholder entity (target) under joint and several liability provisions.

Queensland and Unit Trusts

QLD also has a trust look through regime that taxes dealings in certain unit trusts as if there was a dealing in the underlying QLD dutiable property (such as land and goodwill/IP). These provisions are broad and look to trace through downstream partnerships and trusts as well as companies in certain cases. This is an important issue to consider where a unit trust is a party to any steps of the corporate carve-out project.

Restructuring

In preparation for a corporate carve-out, assets/property may be transferred to or from entities within the corporate group. As stamp duty focuses on the legal form, nature and substance of a transaction and not the economic outcome (i.e. the assets/property remain owned by the same ultimate owner), there will likely be a dutiable event on these restructuring steps. However, there are corporate reconstruction exemptions or concessions that may apply to reduce the stamp duty exposure if the requirements for the relief are met.

Corporate reconstruction relief can also apply in some jurisdictions where there is an interposition of a new company between a landholder company and its current shareholders provided all other requirements are met.

General Requirements

Corporate reconstruction relief will require the transferor and transferee to be at least 90 percent group members in terms of share (or unit) ownership and voting control. Generally, inter-group transactions involving unit trusts are allowed with the key exceptions being QLD and the Northern Territory (NT).

In addition, both QLD and the NT require the transferor and transferee to be 90 percent group members for a period of at least three years before the restructure transaction. There are limited exceptions to this three-year pre-association requirement but should be considered if the time requirement may not be met. In Tasmania, the pre-association period is 12 months with a "new" entity exception, whilst other jurisdictions (NSW, VIC and WA) do not have a pre-association requirement which is helpful.

Further, WA, QLD and the NT have a three-year post association requirement for the transferor and transferee that needs to be maintained otherwise the exemption is withdrawn and the exempted stamp duty becomes payable (plus interest and penalties). There are exceptions to this three-year post-association requirement such as being wound up/liquidated within the corporate group or degrouping as a result of an initial public offering (IPO).

Each jurisdiction also has specific requirements that need to be met. Relief is not automatic as the relevant Revenue Office needs to be satisfied that all requirements are met. This should be discussed prior to implementing any restructuring steps.

Exemptions vs. Concessions

Most Australian jurisdictions provide a full exemption from stamp duty for a corporate reconstruction transaction. However, VIC and NSW only provide a 90 percent concession so 10 percent of the stamp duty otherwise payable will still need to be paid.

In VIC, if the same underlying dutiable property is transferred multiple times as part of the restructure but within 30 days of the first transaction, only one lot of the concessional stamp duty is payable. This makes the timing of restructure steps important. NSW does not have a similar provision like VIC so it would be important to understand any commercial drivers for multiple steps involving the same underlying NSW dutiable property.

Further, as some stamp duty is payable, the Revenue Offices in both states will look at the submitted values and supporting information (valuations, accounts, etc.) closely to be satisfied that the correct stamp duty amount is paid.

Purpose

All of the corporate reconstruction relief rules have a "restructure" purpose test that needs to be satisfied. It is important to manage this appropriately as the Revenue Office may consider certain restructure steps are not for a genuine restructure purpose and seek to deny relief on that basis.

We recommended that advice be sought as early as possible to manage this and other associated risks of applying for corporate reconstruction relief.

Direct Divestment of Entities, Assets or Businesses

Entities

The direct transfer of entities may trigger landholder duty depending on the asset composition owned by the company. Are there land type assets and does their value meet the relevant threshold (generally $1 million to $2 million or more) and the size of the divestment, noting taxing threshold for companies starts at 50 percent whilst units (except QLD – see below) starts at 20 percent? Whilst landholder duty is ultimately an issue for the purchaser, it is important to consider this as the stamp duty cost may impact commercial negotiations.

If the divested entity is a unit trust, the Queensland trust look through provisions will need to be considered as there is no minimum taxing threshold.

Assets or Businesses

The divestment of assets or businesses will be liable to stamp duty depending on what is transferred and whether there is any dutiable property involved. There is an important consideration whether as a matter of substance there is a transfer of assets or a transfer of business. If there is a transfer of a business, then as a matter of general law, the goodwill of that business is also transferred. This potentially brings a material intangible asset value into the stamp duty net.

The analysis will consider a number of factors, including but not limited to:

- Understanding how the assets/division are used or operates before and after the transaction (e.g. if the seller continues to operate its business after the divestment);

- Understanding what intellectual property will be transferred as part of the transaction (business names, trade marks, etc.);

- Understanding if employees move, what correspondence is provided to them and whether it refers to a transfer of a business;

- Understanding what any intangible value can be attributed to; and

- Understanding that any proposed public announcement and/or a media release refers to a sale of a business.

The issue of whether a business is being transferred can be an important consideration for purchasers as that can be part of the commercial discussions for a future corporate carve-out transaction.

GST Implications

Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a broad-based federal tax of 10 percent levied on sales of most goods, services, rights, real property and other things made by GST-registered suppliers within Australia. Whilst the GST in question is payable by the supplier, in a commercial context, this cost is generally passed on to the recipient of the supply.

Where an individual or entity is registered for GST, it can, subject to certain exceptions, recover the GST paid on its acquisitions as an input tax credit such that the ultimate cost of GST is passed down a supply chain to the end consumer or the first GST-registered entity so that it's not entitled to recover an input tax credit in full.

The GST payable on supplies, and input tax credits claimable on acquisitions, are reportable in periodic Business Activity Statements (BAS), with the net position either payable to or reclaimable from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Transfer of assets and entities

Assets

As noted above, GST is generally payable on the transfer of assets between Australian resident parties. Whilst this GST can often be recovered as an input tax credit, this can have the following additional implications:

- The GST will need to be funded for the period between payment and claiming of a credit (which can be up to five months), giving rise to a cash-flow funding cost; and

- Stamp duty is payable on the GST-inclusive consideration or market value, such that any GST payable on an asset transfer can increase any duty payable notwithstanding that the GST itself is recoverable.

The provisions on GST grouping or GST-free supplies of a going concern outlined below are therefore often relied upon to manage the above.

Entities

The sale, purchase or issuance of shares, units or partnership interests is a financial supply and not subject to GST. Financial supplies are input taxed or potentially GST-free where a counterparty is a non-Australian resident.

Whilst no GST is payable on a financial supply, where the supply is input taxed, the GST incurred on related acquisitions (e.g. tax, legal and financial adviser costs) will only be recoverable in full where a de minimis threshold known as the Financial Acquisitions Threshold (FAT) is not exceeded.

Broadly, an entity will exceed the FAT where the GST incurred on acquisitions related to financial supplies exceeds either $150,000 or 10 percent of the GST incurred on all acquisitions (i.e. financial and non-financial) over a rolling 12-month period.

Where the FAT is exceeded, a reduced input tax credit (i.e. 75 percent or 55 percent depending on the entity in question) may be available on certain specific costs.

Accordingly, whilst no GST is payable on the transfer of an entity itself, there can be 'GST leakage' on related expenses which can be material depending on the costs in question.

GST grouping

Where entities are members of the same 90 percent owned group, account for GST on the same basis, have the same tax periods and satisfy certain other requirements for trusts and partnerships they may elect to form a GST group. An agreement in writing between the parties and a notification to the ATO is then required to form, change or dissolve a GST group.

Where entities are members of a GST group together, only one BAS is required for the group per tax period. Supplies between members are disregarded and input tax credit recovery is considered on a group wide basis.

One entity is nominated as the representative for the group and is primarily responsible for the GST liabilities of the group, with the other members being jointly and severally liable in the event that the representative member defaults. This can result in exposure to historic GST liabilities of other entities even after they exit a GST group and are sold to a third party.

The liability position above can be contractually managed where the members enter into an Indirect Tax Sharing Agreement (ITSA). An ITSA limits each member's liability for a tax period to their contribution amount (broadly, their liability calculated as if not a member of the group) and allows for a 'clear exit' to be obtained where an entity exits the group.

A clear exit involves the calculation and payment of an amount for the tax period of exit which allows the entity to leave with no further liability for that period (noting clear exit for GST is limited to the tax period of exit and so is not as broad as the income tax concept).

In a restructure context, it is therefore common for transfers of assets or entities to be made within a GST group to alleviate the costs above relating to GST. However, to manage the liability of the parties in question, it is prudent to ensure an ITSA is in place and that any necessary administrative matters and ATO notifications (i.e. to form, join or exit a GST group) are done in a timely manner.

Supplies of a going concern

Where a complete division or business unit of an entity will be sold (either within a corporate group or externally) it may also be possible for the transfer to qualify as a GST-free supply of a going concern.

Broadly, a transfer to a GST-registered recipient can qualify as a supply of a going concern where the parties agree to the treatment in writing and the supplier supplies "all things necessary" for the continued operation of an identifiable enterprise.

What comprises "all things necessary" is a question of fact to be considered on a case-by-case basis, noting that the requirement may not be satisfied where the relevant assets are to be transferred from multiple entities in a corporate group or if particular assets are excluded from the transaction perimeter.

Where the relevant requirements for a going concern are met, no notifications to the ATO are required and so, in a restructure context, this can often be an administratively more straightforward and time efficient option than GST grouping.

Other relevant administrative considerations

In addition to the GST implications of any asset or entity transfers, consideration should be given to any associated impact on relevant GST systems, controls or contracting impacted by the carve-out.

Originally published by 09 April, 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.