The acceptance of 3D signs as trade marks is well established, but the grounds for refusal, including whether the public considers 3D signs to be trade marks or whether they are "necessary" for a technical function of the product, continue to be disputed. Two recent cases offer further guidance.

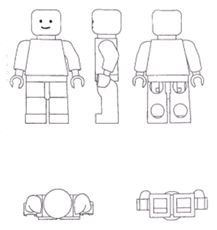

Lego Manikin

On 16 June 2015, the EU General Court (the "Court") delivered a judgment on invalidity proceedings between Best-Lock (Europe) Ltd and Lego Juris A/S (Case T-396/14, Best-Lock (Europe) Ltd v OHIM – Lego Juris A/S). The case concerns the registration of Lego's manikin as a Community trade mark.

On 18 April 2000, Lego registered the 3D shape of its well-known manikin figure as a Community Trade Mark with the OHIM.

The registration was contested by Best-Lock which filed an application seeking a declaration of invalidity of the trade mark on the basis of Article 52(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on Community trade mark (the "CTM Regulation"). Under Article 52(1)(a) of the CTM Regulation, read in conjunction with Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of the same Regulation, a Community trade mark will be declared invalid if it consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

The Cancellation Division rejected the application and the OHIM dismissed Best-Lock's appeal. Best-Lock then brought the case before the Court. According to the Court, the technical result invoked by Best-Lock – the fact that the toy figure could be combined with other building blocks – was too general. The Court therefore held that Best-Lock had failed to show that any technical result could be attributed to the shape of the Lego manikin and had therefore failed to submit sufficient evidence contesting the interpretation or application of EU law made by OHIM. Since the Court's review is limited to a review of the application of law, it rejected the complaint as inadmissible.

In the process, the Court also gave guidance on the use of the terms 'exclusively' and 'necessary' under Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of the CTM Regulation. According to the Court, this provision ensures that shapes of goods which only incorporate a technical solution, and whose registration as a trade mark would therefore impede the use of that technical solution by other undertakings, should not be registered.

First, the Court held that the condition of 'exclusivity' is not satisfied in the case at hand as not all the essential characteristics of the manikin perform a technical function. The manikin's shape gives it a human appearance, making the head, body, arms and legs essential characteristics. They do not entail any 'technical' result.

Similarly, the Court considered that it is not obvious that the figure's hands, the protrusion on its head and the holes under its feet and inside the backs of its legs serve a technical function, and if so, what the function is. Either way, the listed characteristics do not constitute essential characteristics of the shape in question.

Second, the Court held that the condition of 'necessity' is not fulfilled either. The shape, as such and as a whole, is not necessary to enable the figure to be joined to interlocking building blocks (which was the technical result unsuccessfully argued by Best-Lock). The shape simply confers human traits on the figure in question, and the fact that it represents a character and can be used in a play context is not a technical result.

KitKat four-fingered chocolate wafer

On 11 June 2015, Advocate General Wathelet delivered an opinion on a request for a preliminary ruling from the High Court of Justice of England & Wales, Chancery Division, Intellectual Property (Case C-215/14, Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd).

In this case, Nestlé had applied, on 8 July 2010, to register a 3D sign representing the shape of a four-finger chocolate-coated wafer bar as a trade mark in the United Kingdom and the Trade Marks Registry of the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office had accepted the application. When it was published for the purposes of opposition, Cadbury filed an opposition on the basis of Article 3(1)(b) and (e) of Directive 2008/95/EC of 22 October 2008 on Trade Marks (the "Trade Marks Directive").

The case eventually came before the High Court, which submitted three questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (the "ECJ") for a preliminary ruling.

The first question sought to determine when the public would see the sign as a trade mark. Under the Trade Marks Directive, trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character should not be registered and if registered, should be liable to be declared invalid. However, under Article 3(3) of the same Directive, a trade mark should not be refused registration or be declared invalid in accordance with paragraph 1(b) if, before the date of application for registration and following the use which has been made of it, it has acquired a distinctive character.

As regards the proof required to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness, the Advocate General is of the view that it is insufficient for the applicant for registration to prove that the relevant class of persons recognises the trade mark in respect of which registration is sought and associates it with the applicant's goods or services. Instead, the applicant must demonstrate that only the trade mark in respect of which registration is sought, as opposed to any other trade mark which may also be present, indicates, without any possibility of confusion, the exclusive origin of the goods or services concerned.

In its second question, the High Court asked whether the registration of a shape as a trade mark is precluded by Article 3(1)(e)(i) and/ or (ii) of the Trade Marks Directive. Article 3(1)(e)(i) and (ii) provides that signs which consist exclusively of (i) the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves or (ii) the shape of goods necessary to obtain a technical result, do not qualify for registration. In the case at hand, the High Court considered that the shape consists of three essential features, one of which results from the nature of the goods themselves (the basic rectangular slab shape) and two of which are necessary to obtain a technical result (the presence, position and depth of the grooves running along the length of the bar, and the number of grooves, which, together with the width of the bar, determine the number of 'fingers'). It sought to know whether, in such a situation, trade mark registration should be refused under Article 3(1)(e)(i) and/ or (ii) of the Trade Marks Directive.

According to the Advocate General, the referring court was essentially asking whether the criteria set out in Article 3(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Directive could be applied cumulatively. The Advocate General believed that although grounds for refusal of registration cannot be applied in combination, there was no objection to them being applied cumulatively to the same shape since they operate independently of one another. Therefore, the Advocate General confirmed that the Directive must be interpreted as precluding the registration of the shape mark in question, provided that at least one of the grounds for refusal applies fully to the shape.

In its third question, the High Court sought to know whether Article 3(1)(e)(ii) of the Trade Marks Directive should be interpreted as precluding registration of shapes which are necessary to obtain a technical result with regard to the manner in which the goods are manufactured, as opposed to the manner in which the goods function.

According to the Advocate General, the reference to the technical solution required to incorporate a function into the product includes "the manufacturing process". Therefore, registration is to be precluded not only with regard to the manner in which the goods function, but also with regard to the manner in which they are manufactured.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.