EDITOR'S COMMENT: 2012 – WHERE ARE WE GOING?

By Adrian Wild

Since issuing its proposed public benefit entity accounting standard, the UK Accounting Standards Board has decided not to issue separate guidance for public benefit entities.

2012 looks to be an interesting year for charities. The economic outlook continues to be very uncertain. As with other European countries, UK unemployment continues to rise. Demand for many charities' services will also increase.

While we hope that few charities will succumb, we highlight possible actions for charity trustees should the worst come to the worst. Low interest rates help individuals struggling with debt, but reduce income for many charities.

However, on a more optimistic note, by careful selection of investments it is possible to generate higher income yields.

With a focus on service delivery and matching costs to available income, increasing regulation is the last thing that charities need. Here there is some good news – the Charities Act 2011 was recently passed. This hasn't changed the law, but has made it more accessible.

We are also hopeful that the review of the Charities Act 2006 will, in time, enhance the existing law. The significant changes to UK accounting are likely to be deferred (to 2015) and further consultation will take place in the coming year. Hopefully, the changes for charities will not be onerous.

And finally, after much procrastination, we are promised VAT legislation which should help charities share costs and/or work in consortia by removing the 20% VAT cost that they currently suffer. Although HMRC will impose eligibility criteria, we are confident that this will allow charities to improve efficiency and deliver greater services to their beneficiaries.

PERFORMING A U-TURN

By Fiona Reid

In our autumn 2011 charities newsletter we reported on the UK Accounting Standards Board's (ASB) proposed public benefit entity accounting standard, the FRSPBE, which was issued in exposure draft form for comment in March 2011. Since the publication of that newsletter, the ASB has decided to incorporate the requirements of the FRSPBE into the Financial Reporting Standard for Medium-sized Entities (the FRSME) and not issue separate guidance for public benefit entities (PBEs). The ASB has also decided to update the Financial Reporting Standard for Smaller Entities (the FRSSE) to require PBEs to have regard to the PBE requirements of the FRSME.

We noted in the previous edition that the effective date for application of the new accounting standards had been put back from July 2013 to January 2014. However, in November 2011 the ASB announced that this was likely to be postponed even further, to 1 January 2015. This delay may have a knock-on effect on the publication of the charities Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP), as certain modules of the new SORP are in draft format subject to the publication of the final version of the FRSME.

The ASB is considering the feedback received in response to the consultation on the FRSPBE exposure draft and has tentatively agreed to change the proposed treatment of donated goods. The change will allow for income to be recognised when goods are sold if it is not practical or beneficial to estimate the fair value of the goods at the point they are received by the entity. The ASB hopes that this will mitigate the concerns raised during the consultation period in respect of the recognition of low value items donated to charity shops. This does appear to go some way to reducing the issue, but still leaves significant room for inconsistency of approach between entities and therefore is not an ideal solution. The option of a cost-benefit argument may be difficult to apply in practice and could lead to disagreement between PBEs and their auditors.

The ASB has also made further announcements in relation to property held primarily for the provision of social benefit, for example housing properties for social rent. The draft FRSPBE required that these be held as property, plant and equipment and did not permit classification as investment properties.

The implication of this was that under the new standards, as they were initially proposed, it would not have been possible to revalue property held for the provision of social benefit. However, the ASB has reconsidered this and agreed that accounting options currently permitted under United Kingdom Generally Accepted Accounting Practice (UK GAAP) will be included in the next draft of the FRSME. This means that it should be permissible to include properties held in property, plant and equipment at a market valuation instead of at cost.

The ASB has announced that a revised exposure draft of the FRSME will be issued which incorporates the changes noted here, so you should expect to see further updates in future issues of this publication.

PRODUCING A REAL RETURN IN AN UNCERTAIN WORLD

By Ian Richley

What should your charity's investment strategy be in the current unusual economic environment? Ian Richley discusses.

Developed economies are likely to remain overshadowed by structural challenges for many years, principally due to demographic trends and excessive sovereign debt, problems that have been looming for a decade but are only now beginning to force changes in living standards.

This economic malaise poses a huge challenge for charities. Despite an inflation rate which has been above the Bank of England (BoE) target rate of 2% for 24 consecutive months and is currently only modestly lower than that of China, interest rates in the UK have been anchored at their lowest ever rate of 0.5% for more than two and a half years and there is little reason to believe that rates will increase any time soon. On the contrary, the BoE recently embarked on a third round of 'printing money' via quantitative easing (QE).

Against such a backdrop, there have rarely been greater headwinds faced by charities aiming to generate income from their assets while maintaining their real value.

The hope is that QE and a period of unusually low interest rates will provide sufficient support to offset the impact of deleveraging, which threatens to push economies back into a more prolonged recession if left unchecked. The effectiveness of QE is difficult to measure. Although it has probably served to prevent an even greater economic downturn in the short term, the long-term ramifications are more worrisome. Indeed, its primary rationale is to provide banks with liquidity and to underpin asset prices. In other words, savers are being encouraged to borrow and investors to speculate in a bid to maintain the purchasing power of their money. The risk is that the current approach being adopted by the BoE could eventually lead to a period of heightened inflation.

So, which assets are likely beneficiaries of this unusual economic environment? Which offer the scope for maintaining their real value while providing the above average level of income typically sought by charities?

Index-linked bonds

Investments that offer the same real return regardless of the rate of inflation are likely to remain in favour with investors. The future returns generated from UK government index-linked bonds are linked to the Retail Price Index (RPI), which is arguably a better reflection of true inflation in the UK than the more commonly cited Consumer Price Index (CPI). Furthermore, RPI has historically risen faster than CPI and there is good reason to believe that this trend will continue. The first UK government index-linked bond was issued in 1981; the market has since grown to represent 20% of total UK government bonds in issue. They are highly liquid and often find particular favour with investors during periods when riskier asset classes, such as equities, are struggling to perform, therefore providing diversification benefits.

Those investors able to tolerate greater risk may consider inflation-linked corporate bonds. While this market is typically less liquid than that of government bonds, the potential returns are generally more attractive to compensate the investor for the higher credit risk. This market is still in its infancy, with a total value of just over £10bn and fewer than 300 sterling issues. Typically they are issued by household names, such as Tesco, or utility companies that benefit from relatively predictable and often inflation-linked earnings streams.

Shares in large multi-national companies

In the current low interest rate environment, large multi-national companies with robust balance sheets and globally recognised brands are typically at a significant advantage over smaller businesses due to their access to capital markets. Such companies can issue debt through the corporate bond market at very low rates of interest, such is the demand from income-starved investors.

A good example is Coca-Cola, one of the most recognised brands in the world. The group pays an average of only 3.8% on current debt and this rate should decline as debt matures and is refinanced. Indeed, it can effectively borrow new money at a little over 1% if this is achieved through the issue of short-dated bonds. Coca- Cola now generates 75% of sales outside North America and its turnover in BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries is growing by more than 25% per annum. It is taking advantage of low interest rates to invest more in countries such as India, where the group recently announced its intention to invest $2bn over the next five years. Coca-Cola shares currently offer a dividend yield of 2.9%.

There are many other shares that have similar characteristics to Coca-Cola, which offer investors reasonable dividend yields and scope for positive real returns.

Emerging markets

The IMF recently predicted that by 2030 the Chinese economy will be of a similar size to the US and EU economies combined. Clearly, such long-term forecasts are prone to error but they are indicative of the acceleration in the shift of global power from West to East which is now underway. Historically, UK charities have typically gained exposure to emerging economies indirectly, through shares in companies listed in the West that operate in those economies. This approach certainly has merit, not least as many such shares are relatively stable and offer attractive dividend yields.

However, this can be complemented by investing through collective vehicles that invest directly in emerging markets, focusing upon higher yielding and defensive sectors such as utilities and telecommunications. These markets have evolved enormously since the Asian crisis of the late 1990s and management have become more aware of the need to provide investors with steadily rising dividends. In 1995 there were just 75 emerging market listed stocks that offered an income yield in excess of 3%; by 2010 this had risen to 205. Indeed, of the approximately 800 companies currently listed in the MSCI Emerging Market Index, over 25% offer income yields of over 4%. Furthermore, the average company listed in emerging markets is less indebted and pays out less of its overall profit in dividends, indicating reasonable scope for dividends to rise.

Maintaining a balanced portfolio

Index-linked bonds, shares in multinational companies that have good access to capital markets, and collectives that offer exposure to higher yielding shares in emerging markets are examples of investments that offer reasonable sources of income for investors looking to maintain the real value of their assets in the current unusual economic environment. Nevertheless, these investments should not be viewed in isolation but rather in the context of a reasonably balanced and diversified portfolio that is appropriately positioned to reflect the charity's specific circumstances, objectives and tolerance for risk.

GETTING WOUND UP CHARITIES AND INSOLVENCY

By Alison Maclennan and David Blenkarn

The economic outlook for 2012 continues to be uncertain and this may lead to real issues for a number of charities. We look at the reasons for this and the possible courses of action open to trustees.

With continuing worries about the stability of the eurozone economies, high unemployment and the impact of the future reductions in Government expenditure still to be felt, a great deal of economic uncertainty persists. In that context, many charities will face financial challenges.

The funding sources and activities of charities are incredibly varied. Charities may also have different types of funds, such as restricted funds and permanent endowment, or different types of assets with differing degrees of liquidity. This diversity itself means that at any point in time – regardless of the economic environment – a proportion of charities will be struggling with financial uncertainty and be at risk of insolvency.

Added to this underlying core of usual activity for the sector are increasing numbers of publicly funded charities struggling to survive the effects of the comprehensive spending review. While the review has faded from the headlines, real reductions in Government spending are planned over the next three years, with departmental and administration budgets forecast to reduce from £378bn in 2010/11 to £369bn in 2014/15. This represents a reduction in real terms of over 10% in aggregate, but with spending on the NHS protected, some Government departments are facing harsh cuts, the cumulative impact of which will be felt over the coming years.

Trusts and foundations whose primary income stream is investment-based have not had a comfortable time, but their cautious approach to investment and foresight in dealing with volatility has paid off. Surprisingly, donation income has not suffered as much as had been expected but this may change if the current austere mood continues for a prolonged period and unemployment rises.

Recent reports highlight the concerns in the sector: many finance executives consider that their organisation's solvency is at risk because of the squeeze on funding and reduced donation income. The perception in the sector is that the Government has failed to comprehend what it is charities are being asked to do. The demand for charity services has increased simultaneously with the cuts in funding.

Statistical research by New Philanthropy Capital shows that almost a quarter of charities in the UK were funded directly by the Government to some extent and 13% received more than half their income from the state. A few charities were reliant on the Government for 90% of their income. Withdrawal of funding can result in a charity becoming insolvent very quickly – which has already happened to a number of charities. For example, the Immigration Advisory Service was the largest provider of publicly funded immigration and asylum legal advice. Government reforms removed immigration from the scope of legal aid which meant that the charity's liabilities could not be met from its much reduced income base. A solvent restructure could not be found and as a result the trustees decided that they had no option but to place the charity into administration.

Trustees of charities which are facing difficulties (or where there is uncertainty over the future) should take early advice and consider possible courses of action as follows.

- Restructure operations, increase funding, cut back on costs. The key is to make operational changes as soon as the charity can foresee problems.

- Look to merge the charity with another in the same sector to increase scale and resources. This has been the route to safety for several charities recently and underlines the fact that often bigger is better.

- If a restructure or merger does not look like it will bring an answer, then taking specialist advice from an insolvency practitioner and a lawyer is vital. The trustees will need guidance to ensure that their actions cannot be criticised and that the requirements of the Charity Commission are met.

In considering any action, any legal restrictions on the use of funds or assets must be considered and timely advice is essential.

If a charity cannot pay its debts as they fall due for payment, or if the value of its liabilities exceeds the value of its assets, then the charity may be insolvent. Insolvency law aims to rescue or restructure an organisation and perhaps the sale of a business may be arranged with the proceeds going to the creditors. The difficulty with charities is that a 'sale' is inappropriate. This begs the question as to what is the solution for charities which might be facing insolvency. The common solutions involve restructuring, joint working or merger. Ultimately, a winding up or dissolution may be the only option. The charity trustees may prefer not to wind up the charity as there may be a desire to continue some of the charity's work, saving at least some jobs, expertise and possibly a brand.

Charity mergers are therefore usually born from need. For charities facing a situation where a merger is desirable there is still the task of finding a good merger partner. The need may not just be economic but can arise from a perception that the charity has gaps in its services or expertise. There should be some shared gains and often cost savings too. Finding the right partner can take some time and there are many factors to consider.

DEFINED BENEFIT PENSION SCHEMES: A TICKING TIME BOMB?

By Alison Maclennan and Adam Stephens

Participation in defined benefit pension schemes can have far-reaching consequences for charities.

In the preceding article, we explain that a merger may be the best way for a charity facing a substantial, long-term reduction in income to avoid insolvency. However, past or current participation in defined benefit (DB) pension schemes could be a potential bar to a successful merger.

Defined benefit schemes

A DB pension scheme is one in which pensions paid are based on the retiring employees' salaries, such pensions being paid until the retiree (and sometimes, their spouse) dies.

Recent and forecast increases in longevity have made these schemes simply too expensive for employers. As a result, except in the public sector, final salary schemes have largely been replaced by defined contribution schemes or, in some cases, DB schemes based on average salary.

While longevity has been increasing since the 19th century, the rate of increase has risen significantly over recent decades.

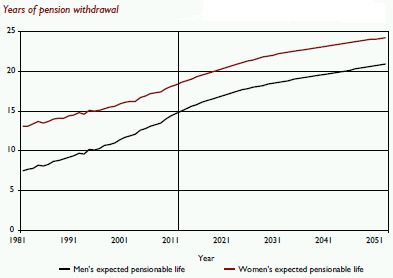

Data from the Office of National Statistics shows that in 1981 a man who joined a pension scheme at the age of 25 would expect to draw his pension for 7.5 years, by 2012 this has increased to 15 years and by 2042 is forecast to increase to over 20 years. Similar trends also apply to women. These trends are shown in the graph below.

The result of these trends has not only been the closure of DB schemes, but also for many schemes to be in deficit. That is, the amount that the scheme expects to pay out is much more than the assets in the scheme. Such deficits can cause significant issues for charities, particularly those looking to merge.

Financial accounting

Financial Reporting Standard Number 17 requires charities to measure their DB pension surpluses or deficits and reflect these in their balance sheets. While this will highlight the existence of a deficit, caution should be used in interpreting this figure: the amount recognised is calculated in accordance with accounting rules and does not actually represent the amount which will be paid in the future.

However, an accounting deficit is usually indicative of a 'real' deficit in the scheme. If there is a significant deficit which has not been addressed, it may raise an issue over the solvency of the charity and its ability to continue as a going concern. Trustees will need to consider how funding a deficit may impact on future budgets. Sometimes providing the scheme with security (perhaps over a building) can help to reduce the cash funding burden.

Leaving a multi-employer scheme

Many charities also participate in multiemployer schemes and the deficits relating to these schemes are not always recorded in charities' balance sheets. Therefore, there may be substantial liabilities of which trustees are unaware.

While a charity continues to have employees in such schemes, there is usually no obligation to make cash payments, other than the normal contributions. However, if an employer leaves a multiemployer scheme, under section 75 of the Pensions Act 2004, the scheme trustees will normally demand that the employer pays off the deficit. Broadly, an employer leaves a scheme when it no longer has any employees in the scheme. This will happen if the relevant employees leave, are made redundant or retire. There are some ways to alleviate the immediate payment but these are complex and require professional advice.

Finally, one nasty tweak is that an employer might have participated in a scheme which had a DB section and a defined contribution section. It might be that the charity no longer has any employees in the DB section and views the scheme as simply a defined contribution scheme. However, any past deficits relating to the DB section will still be an obligation of the charity.

Merging

A key part of any merger is the financial plan which is used to assess the viability of the merged charities. Staff costs are usually a key component of expenditure and pension scheme contributions form part of these costs. Looking to the future, trustees will need to consider the impact of auto-enrolment, whereby all staff will be automatically enrolled in employer pension schemes. Auto-enrolment is being phased in over the next few years, beginning with larger employers in 2012. We expect this to result in increases in employer pension contributions.

If a charity borrows money, the need to fund any pension deficit may also have an impact on existing borrowing, compliance with loan covenants and the charity's ability to raise funding in the future.

A merger may also trigger the need to assess the debt owed to a pension fund under section 75 of the Pensions Act 2004 and possibly pay the debt or make additional or accelerated scheme contributions. In the worst case scenario, an annuity might have to be purchased from a regulated insurance company. If charities are merging due to financial pressure, any accelerated or additional payment requirement may be enough to scupper the plans to merge. If this is the case then winding up may be the only remaining option.

The CFDG has produced some excellent work in its publication The Charity Pension Maze which highlights the particular problems of charities and pension deficits.

|

Perils of a multi-employer scheme Most multi-employer schemes are public sector schemes (for example, NHS, Local Government Pension Scheme, Teachers' Pension Scheme) or schemes with a large number of members. However, for charities in a multi-employer scheme with few active employers, the experience of the Wedgwood Museum charity provides a grim warning of the perils of such an arrangement. The museum had five staff in the 7,000 member Wedgwood pension scheme. When the Wedgwood companies went into administration, as the only entity not in administration, the museum became liable for the entire scheme deficit – a modest £134m. As a result, the museum was also put into administration and the High Court has ruled that the collection must be sold, with the proceeds to be put towards the pension deficit. |

LEGAL UPDATE

By Adrian Wild

Adrian Wild reviews recent and potential changes to charity law.

The Charities Act 2006 (the Act), which applies in England and Wales, received Royal Assent on 8 November 2006. Since that date there have been 17 related Statutory Instruments either enacting various parts of the Act or amending the Act or other legislation. Despite this storm of change, the Act has yet to be fully enacted, with sections relating to charitable incorporated organisations and the licensing regime for charitable fundraising yet to come into effect.

Criticism

The Act has been widely criticised. There has been much concern about the statutory definition of 'charity', which includes the requirement to act for the 'public benefit'. In particular, the impact on charities which charge fees has been subject to much comment.

Other aspects of this legislation have also drawn censure. The Act created the Charity Tribunal, with the aim of simplifying the process for appealing against Charity Commission rulings or having Charity Commission decisions reviewed. While this is a laudable aim, there is concern that the Tribunal's scope of work is too narrow, limiting its effectiveness. The Register of Mergers was created so that there is a record of those charities which cease to exist simply through merging with another. The idea was that legacies due to a merged charity would be able to be received by the successor charity; however, due to the way in which most wills are written, this has proved less effective than expected.

The Charity Commission guidance on public benefit, written in accordance with the dictates of the Act, has also been subject to review by the courts. As a consequence, the Commission was asked to review and revise some of its guidance. However, ultimately the Commission has been forced to withdraw some of its guidance. Whether the changes will have any practical effect remains to be seen.

Review

Uniquely, the Act also contained a requirement that its operation should be reviewed, the requirement being that within five years of receiving Royal Assent a reviewer be appointed for this purpose. The Government has appointed Lord Hodgson to lead the review. Lord Hodgson is president of the National Council for Voluntary Organisations and he also led the Big Society Deregulation Taskforce (the Government-commissioned review of red tape in the voluntary sector).

The key questions the review is tasked with answering are:

- what is a charity and what are the roles of charities?

- what do charities need to have/be able to do in order to be able to deliver those roles?

- what should the legal framework for charities look like in order to meet those needs (as far as possible)?

These questions are supplemented by a number of other matters, including the public benefit requirements, mergers and the operation of the Tribunal. Lord Hodgson is due to deliver his findings in summer 2012, after which a report will be laid before Parliament. Quite what the next steps are will depend on his recommendations, however, based on past form, we should not expect new legislation any time soon.

Other legislation

Ironically, while Lord Hodgson was starting his review of the 2006 Act, the Charities Bill 2011 was wending its way through the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The Bill received Royal Assent on 14 December 2011 and is now known as the Charities Act 2011. The Act consolidates most of the extant English and Welsh charity law into one coherent Act. Given that there have been over 120 changes to the 1993 Act (which to 31 March 2012 remains the primary Act), this Act is much needed. (However, it should be noted that elements of the Charities Acts 1992 and 2006 will remain in force).

Finally, further parts of the Charities Act (Northern Ireland) 2008 have been enacted. All Northern Ireland charities registered with HMRC will be automatically registered with the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland, and other charities will have to register themselves if they meet the criteria. However, the requirements for Scottish and English/Welsh charities which operate in Northern Ireland to register have yet to come into force. Interestingly, as part of his review, Lord Hodgson is charged with reviewing the idea of having a UK-wide definition of charity and ways in which the burdens of dual (or even triple) registration can be eased.

SPOTLIGHT ON VAT

By Ian Stinson

VAT on postal charges

Many charities and not-for-profit organisations will be affected by the introduction of VAT on a number of Royal Mail postal services from 2 April this year.

Some postal services, including stamped or franked first and second class post, will remain exempt from VAT as they are part of the Royal Mail's universal service obligation. Other postal services subject to regulatory price control will also remain VAT exempt.

However, VAT will be charged from 2 April 2012 on many other postal services, including business collections, Special Delivery" Next Day (on account only) and door to door. A full list of the postal services that are changing their VAT status on 2 April, can be found on the Royal Mail website at the following address: www.royalmail.com/customerservice/ terms-and-conditions/vat-changes

The addition of 20% VAT on postal services will be a significant cost increase for organisations that cannot reclaim all of their VAT. For those that are partly exempt and able to reclaim a proportion of their VAT costs, it may be an opportune time to review their VAT recovery calculations to try to mitigate the irrecoverable VAT costs.

Charities and other organisations that are not VAT registered, should ensure that they are taking advantage of other measures to minimise the VAT cost of postal campaigns, such as the zero-rating of campaign packs where individual elements might otherwise attract VAT.

Whether or not charities are normally able to reclaim some VAT costs, the changes in April might still involve a bottom-line cost. If you use a franking machine, Royal Mail has said that the services on which VAT will be charged from April can only be purchased through 'smart' franking machines, which will also produce VAT invoices; the VATable services cannot be purchased through older franking machines.

VAT cost sharing exemption

In the autumn 2011 edition of the charities bulletin, we reported that HMRC was in consultation about the implementation of a cost sharing VAT exemption. In the Chancellor's Autumn Statement on 29 November it was announced that legislation will be introduced to implement the cost sharing exemption in 2012.

This exemption will allow groups of eligible organisations, including charities, academy schools, universities, higher education colleges and housing associations, to provide services to each other without generating an irrecoverable VAT cost, provided the services are directly necessary for the consortium member to carry out its exempt and/or non-business activities.

Newly formed cost sharing consortia can apply the VAT exemption from the date when the 2012 Finance Bill receives Royal Assent. HMRC has said that it will publish comprehensive guidance on the conditions and eligibility to use the cost sharing exemption in advance of its legal effect. HMRC has acknowledged that it cannot prevent cost sharing arrangements from being formed prior to the new legislation coming into force because the exemption already exists in EU VAT law. However, HMRC does warn that incorrect implementation of the exemption before it becomes UK law could result in it taking action to recover any VAT that should have been charged, including the charging of penalties.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.