Using real estate to address the deficit

The economic downturn has resulted in reduced profits and cashflows for many companies. This weakening of employer covenants in the eyes of pension scheme trustees' has in turn led to higher funding targets and requests by trustees for larger cash contributions. Understandably, companies have been keen to consider alternative funding structures to help meet their obligations. There has been an increasing focus, as a result, on the use of guarantees, pledges over assets and other forms of contingent assets to help satisfy trustees.

More recently, structures that provide schemes with an investment, backed by valuable and income producing group assets, have proved very attractive to corporates and trustees alike.

To date asset backed funding structures have been implemented by a range of companies, including Whitbread, Marks & Spencer and Sainsbury's (all using property assets), amongst others.

The various structures implemented to date have funded more than £2 billion of aggregate deficit with predictions that this trend will continue to gain momentum.

A key factor when considering alternatives to cash funding is the balance of complexity with the effectiveness of the option in addressing scheme funding (both for recovery plan and Pension Protection Fund (PPF) levy purposes).

The key alternatives fall into three broad categories:

1. Contingent arrangements such as parent guarantees or legal charges, may help trustees to accept longer but entirely cash funded recovery plans. These structures however, do not enable the scheme to recognise a plan asset and there is no immediate improvement to scheme funding.

2. Direct asset funding structures, on the other hand, do transfer real value to schemes. Property can be sold or transferred directly to a scheme and recognised as a plan asset and the corporate can benefit from tax relief on the value of the contribution, just as it would do with a cash contribution. However, in doing so, the company loses control of the asset – along with any potential profit and loss benefit on future uplift in value – which may prejudice future operational flexibility.

3. Asset backed funding structures such as those mentioned above, albeit more complex, can immediately repair a significant proportion of scheme deficits. At the same time they can reduce PPF levies, build in protection against future overfunding of the scheme, and help to reach agreement on a wider recovery plan by utilising 'lazy' unencumbered balance sheet assets in a manner which may previously have required bank involvement e.g. through debt financing or sale and leasebacks – and with the additional costs and fees that those options would entail. The corporate retains operational flexibility and achieves an affordable cashflow profile.

Putting real estate to work

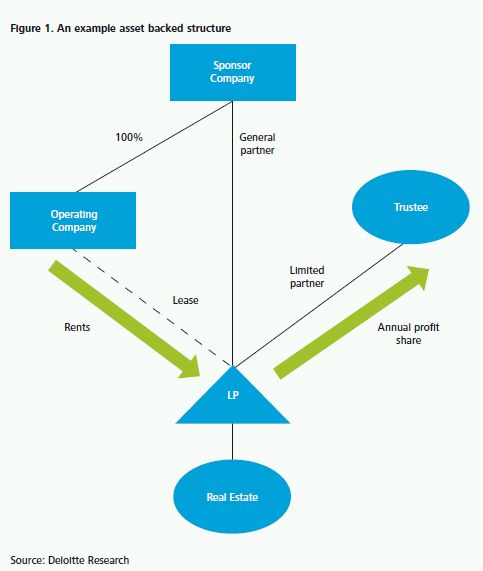

Asset backed funding structures involve the sponsoring employer group establishing some form of special purpose vehicle, commonly in a form of limited partnership, into which group assets such as real estate, would be transferred. The limited partnership leases the assets back to an operating company within the group for a market rate rent. The partnership owns the valuable assets in its own name, ring-fencing the assets from the wider corporate group and its creditors.

The corporate group would then make a monetary contribution to the pension scheme and the scheme would make an investment into the limited partnership.

Cash efficient profile

The pension scheme would be entitled to an annual share of the partnership income profits over a period – say 15 to 20 years, effectively equating to a valuable bond-like investment, backed by assets, that pays an attractive coupon over the term of the structure.

The scheme would also be entitled to a capital sum at the end of the term of the structure; the corporate group would retain the rights to future capital profits, in addition to operational control and flexibility, and the right to substitute assets. However, the value of the assets held by the partnership would need to be sufficient to ensure enough profits are made by the partnership to pay the annual income share to the trustee and to provide adequate collateral to support the upfront value of the investment that the trustees have made in the partnership, should the sponsoring employer find themselves in a distressed situation.

Enhanced protection for trustees

The partnership investment held by the scheme is backed by group assets that have independent, third party resale value, providing the trustee enhanced protection, should the sponsor covenant weaken or, in the worst case, the sponsoring employer become insolvent.

The limited partnership takes legal title to the assets, ring-fencing them from other creditors of the group. Trustees recognise that as a result their security position is significantly improved compared to a conventional cash based funding plan. This can help them to be more receptive to other requests of the corporate for example, in agreeing to wider changes to member benefits.

It is of course, important to consider how this structure interacts with group banking arrangements, however, the structures are typically viewed in a positive light given the company is proactively addressing the deficit whilst improving cashflows within the business. The trustees also need to ensure that they are happy that the structure does not breach restrictions on employer related investments and investment diversity. Guidance has recently been published by the Pensions Regulator to help trustees in this area.

Choice of assets

In principle, the range of assets can include almost anything, provided they have independent value and can generate an income stream.

Real estate is the most obvious choice and its tangible nature makes it easier for trustees to understand. That being said, more esoteric assets such as intellectual property, receivables or stock such as whisky in one structure are increasingly being considered.

No change to accounting and tax profile

Whilst the accounting treatment of the structures may vary depending on the particular commercial arrangements made with the pension scheme, they often have no impact on groups' net asset positions with the partnership being fully consolidated in the group accounts. In such cases, the IAS 19 pension deficit figure shown in the consolidated accounts remains unchanged, as the partnership interest held by the pension scheme is considered to be part of the group's overall liability to the pension scheme.

Likewise, the tax treatment of the structure should follow the economic profile of the transaction, with relief available in the same way that it would be if the contribution had been made in cash, although confirmation should always be sought from HMRC.

Asset backed funding structures such as those described above, can immediately repair a large proportion of a deficit but at the same time defer large cash outflows that would otherwise be required under traditional cash contributions. The structures deliver schemes with predictable, bond-like investment returns from the underlying income streams such as property rents, over a medium term period of say 15 to 20 years. This can complement existing de-risking strategies and at the same time, the deferral of net cash outflows (with minimal impact on the group accounting position) aligns with wider commercial objectives. Furthermore, for many companies the traditional cash funding approach would mean borrowing funds or using cash that could otherwise be invested in the business.

The costs of external lending facilities or the marginal cost of capital are currently markedly higher than the discount rate on the majority of pension schemes – emphasising the cash flow and treasury benefits that can be achieved through these alternative structures.

Where next?

The attractions of non-cash asset backed funding approaches are obvious, helping companies achieve wider objectives whilst addressing scheme deficits in a cash efficient way. They also represent an opportunity for companies to make their real estate portfolios work harder for them, and in a more cost effective way, than through traditional routes to realise capital, such as sale and leasebacks.

And whilst asset funding is not going to solve the issue of what companies do with their defined benefit pension schemes in isolation, it can play a major, complementary role to other strategies to help mitigate pension risks.

As we look forward, more companies are likely to consider the use of real estate and other assets to fund scheme shortfalls, or to work with their trustees in structures to raise third party capital (illustrated by the recent joint venture between Tesco plc and its pension scheme).

The challenge of funding pensions is not limited to the private sector. Managing legacy and ongoing pension liabilities are just as relevant to the public sector, as we watch the current Coalition Government tackle the cost of public sector pensions. Local authorities are also starting to consider ways in which their pension schemes can help to fund stalled infrastructure projects as spending cuts begin to take hold.

Pensions will continue to be a dynamic financial challenge to both the private and public sectors – and as a result we expect to see increasingly innovative thinking to address those risks.

Property and Local Government

Background

There is no doubt that effective use of property assets will play a key role in helping local authorities deliver their services and continue to enable much needed economic regeneration during these difficult times. There are real opportunities for the private sector to become involved with both these challenges. We consider below those changes that are afoot and how authorities are looking at them, explain how the local Government accounting regime may affect these and examine some of the property based solutions which are being used.

Changes

Public sector organisations are under huge budgetary pressures to deliver efficiencies. The imminent budget cuts have been well publicised and are having a big impact on the sector. This will lead to major changes in the way local Government delivers its services. Some of the high level issues local authorities are currently assessing are:

- The structure each authority should adopt in order to best deliver services, with many local authorities moving towards a "commissioning model" involving stream lined in-house staff and a much greater reliance on private sector contractors to deliver services.

- How best to work in partnership with other public sector organisations; this includes neighbouring local authorities sharing senior officers and management teams.

- How to implement the Localism agenda, which has become clearer since the publication of the recent Localism Bill.

- The impact of the wider roles local authorities are being asked to take on, particularly in the areas of education and economic regeneration.

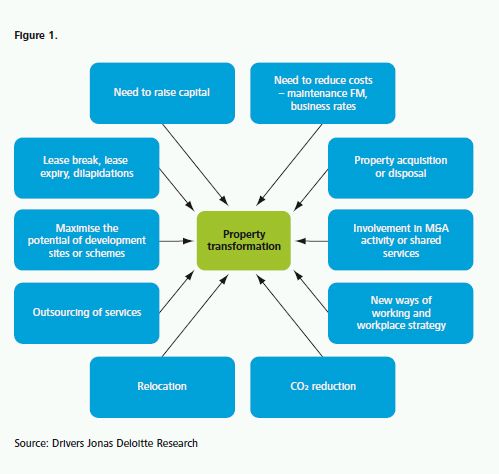

These will all have a major impact on the property requirements of a local authority – both operational (the properties a local authority needs to deliver their services) and non operational (assets held for regeneration or investment purposes).

Local authorities' property assets continue to be a key element in delivering these changes. While they don't drive them in isolation they are a core component (see Figure 1).

As well as these major structural changes, local authorities are playing a more pivotal role in delivering regeneration and economic growth such as through the newly created Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs). There are a number of ways they are using property, either directly or indirectly, to achieve this.

We consider overleaf the accounting regime local authorities work within which influences how they involve the private sector in generating value for their assets.

Local Government accounting regime

The public sector accounting regime is arguably more testing than that of the private sector. In the public sector, expenditure budgets are normally fixed and outturns need to be achieved within tight tolerances. There are a number of different types of spending mainly capital expenditure (i.e. spend on property, plant and equipment) and revenue expenditure (which are recorded separately) and there are limited opportunities to flex budgets, within the year or between years.

This framework affects the way funding for programmes and projects is considered. In the private sector the focus is on payback periods, profits and cash flows. In the public sector, in addition to cash funding requirements and the total costs and associated benefits (quantitative and qualitative), financial accounting can also be a key factor in achieving project approval.

To further complicate matters, the accounting regime and budgetary framework are different between central Government, the NHS and local Government. In many cases these differences are subtle and occasionally there is a need to follow the funds that flow through the central Government framework and on into local Government.

With respect to financial accounting we have seen the rules applied in the public sector change. Central Government departments and health bodies adopted International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) accounting from 1 April 2009. Local Government followed suit from 1 April 2010. IFRS can significantly impact how property transactions, particularly those structured through partnership arrangements, are accounted for now and in the future.

Case study 1

Deloitte became involved in, prior to the 'financial close' of a partnership funding vehicle arrangement. The business case involved external (non-Governmental) funding in the form of loans being passed through an 'arms length' body onto third parties. However, after being asked to assess the IFRS accounting treatment, it became clear that our public sector client retained control, such that it was not an 'arms length' body and the funds flow would need to be included in our client's budget.

It was fortunate for the client's objectives that this was identified before any contracts had been signed, meaning that it was possible to renegotiate the terms so that the 'arms length body' was no longer deemed to be controlled by our client. Had this not been identified until after legally binding contracts had been entered into, our client would have faced un-manageable pressures on their budgets.

Case study 2

An agency planning to enter into a partnership agreement, expected that most of the transaction would score to their resource budget. In practice, due to the risk, reward and control arrangements, most of the costs were capital costs and so were not affordable within the agency's existing capital budget.

Our analysis assisted the agency in negotiations with the preferred supplier, which led to a restructure of aspects of the arrangement, such that it was then possible to then score the spend as revenue in nature.

In local Government there are two distinct accounting bases that need to be understood. Again, the financial accounting is under IFRS, but the Capital Finance Regulations also need to be considered. This is a legal framework which provides reconciliation from the outturn under financial accounting to the required level of council tax. This reconciliation is included in the annual accounts of the local authority, and partly explains the complexity of a set of local Government accounts. Under the Capital Finance Regulations various adjustments are required to the financial account numbers; for example depreciation is reversed out and a minimum revenue provision, based on the asset base, is reflected instead. There is also a significant level of ring fencing of reserves for specific reasons.

Due to the complexity of public sector finances as outlined above, public sector managers do not always fully appreciate the budgetary implications of particular transactions they plan to progress, especially if they do not closely involve their finance colleagues. Case studies 1 and 2 are examples of where the budgetary implications were not fully appreciated.

There is clearly significant complexity for public sector managers to address within the financial framework. For a private sector organisation, including real estate professionals, looking to work with the public sector (central Government, the NHS or local Government) the challenge might be even greater due to unfamiliarity with the requirements. However, we believe that the private sector does need to understand the financial framework, particularly as the budgetary position tightens in this period of austerity.

By understanding the framework, private sector real estate professionals will be able to take ideas proactively to the public sector. They will also be well positioned for the range of innovative real estate arrangements which are likely to develop over the next few years

Real estate opportunities

Local authorities' property portfolios are being put increasingly under the spotlight to see how they can be used efficiently and effectively to help deliver services.

There are many ways this is being achieved depending on what the Authorities' priorities are e.g. revenue capital and economic development.

We focus on three areas below.

Disposal of surplus assets – raising capital

Local authorities hold a register of all of their assets. These are divided into operational and non operational. Surplus assets should be programmed for disposal. There is a legal obligation to secure "best consideration" on disposals – this does not necessarily mean having an open competition (unless procurement legislation applies) but most authorities usually openly advertise opportunities.

For more complex transactions with local authorities where they are exercising control as landowner over what happens with the end development, European case law has determined these need to follow an open public procurement route. Previously, authorities could adopt a more pragmatic approach to whom they worked with on these, providing they could still demonstrate they were achieving best consideration.

There are a number of different routes this procurement process could adopt. They have the potential to be extensive and expensive, unless they are managed properly and the most appropriate route adopted on day one.

There has been a lot of press coverage about the amount of central Government assets coming to the market. Generally, however, authorities are unlikely to be sitting on lots of surplus assets. Often the ones left in the portfolio are the more difficult/management intensive ones which require uncertainties to be removed, typically relating to planning, re-provision of onsite facilities and physical impediments to development title issues. Authorities will need to balance the time and cost required to resolve these in-house with the discount to value adopted by potential purchasers.

Whilst inevitably there are likely to be pressures for quick sales, most authorities are reviewing their estate generally in the light of future structural changes to identify how they should use these most effectively. This is likely to involve a range of options rather than a single solution.

These structural changes in response to the spending cuts, in particular reductions in staffing numbers, further outsourcing, sharing of facilities between authorities, cutting services where possible, hot-desking and home working, will mean a large reduction in the space local authorities occupy and using what is left more efficiently. Large scale disposals of older, smaller, less efficient buildings and investing in new or refurbished buildings with larger/more flexible floorplates is likely.

A major difficulty with Government plans for property disposals is that the recent property downturn will make local authorities reluctant to sell at what is considered to be close to the bottom of the market, particularly for the more secondary property that local authorities would want to dispose of. For this type of property, private sector demand is weak due to the risks of low occupier demand and rental growth, high vacancies, short leases and the high capital cost of obsolescence and sustainability. Therefore, rather then selling off buildings or sites in a weak market, many local authorities may be more likely to consider acquiring property sites and redeveloping or refurbishing existing buildings. This would allow them to take advantage of lower prices and low interest rates, to achieve longer term floorspace efficiency aims, thereby saving on future rental payments.

Most local authorities are able to borrow capital providing they are able to meet the interest payments from their revenue budget. Local authorities are in a number of cases using this facility to fund the acquisition of strategic assets, often to help with their regeneration remit.

There is also the opportunity for local authorities to raise capital via sale and leasebacks, typically of properties they occupy. However, while this may help with capital programmes, it does impact on their revenue budgets as they are taking on a long term commitment to pay rent – often not an attractive proposition for an authority.

Corporate Structures e.g. Asset backed vehicles

Asset disposals and one off transactions don't always allow longer term value to be captured. This is one of the benefits of corporate structures which may last over a 15-20 year period.

Local Asset Backed Vehicles (LABVs) have grown in popularity over recent years even though they have been around for over 10 years. They are in effect partnerships (often established in the form of Limited Liability Partnerships) where the public sector injects value generated from their assets and the private sector brings leverage in the form of expertise, capital and access to funding. They are to be distinguished from Private Finance Initiatives (PFI). The latter are based upon the relatively straightforward concept that a public sector body procures buildings/infrastructure and/or services from the private sector in return for promising to pay annual payments over an extended period of time. Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) reflect the public and private sectors coming together in joint ventures that in the case of LABVs can be secured against assets and realisable development value, rather than being solely revenue reliant.

Public sector bodies have promoted LABVs for different reasons. These include combinations of income protection, delivering specific civic facilities, achieving delivery of regeneration projects and asset value maximisation. There is no ready made model for a LABV and it is not the panacea for solving what to do with residual difficult assets. It can be a costly and time consuming exercise to establish these vehicles. From a private sector partner's point of view if they are considering these types of opportunities they need to ensure the authority has addressed some fundamental issues at the outset in particular:

- What are the Council's objectives for the vehicle? Is it to focus on the specific sites identified or have a more organic/roving relationship with the Council's existing property team and portfolio? Should it focus on sites which require intensive amounts of enabling infrastructure works, or on some of its less capital intensive sites? Is its role to bring sites forward for development and then secure "best of breed" partners on a scheme by scheme basis, or does it want the New Co to build out the projects?

- Have they identified the right initial "basket" of assets? While these can be added to at a later date there needs to be a balance which will ensure the right programming of risk/upfront costs and returns, i.e. some quick wins to repay "at risk" costs incurred by the private sector partner;

- Have they considered the type of partner they require e.g. developer, investor, contractor, consortium, service provider?

- Have they put the right stepping stones in place both in terms of a formal business case and member and officer buy in?

In terms of the overarching structure of a LABV this may have a series of sub-structures to develop specialist areas. Whilst the private sector partner will inevitably need to be procured through an Official Journal of the European Community (OJEU) compliant process, once in place other partners can be introduced for the specialist areas, without the need for a lengthy selection process.

As well as using property assets to encourage regeneration, local authorities are exploring other financial models.

Tax Increment Financing/Community Infrastructure Levy/New Homes Bonus

These three initiatives are important parts of a wider package of initiatives to encourage local growth and enable future economic growth and development. The Government is committed to strengthening the tools that Councils have to promote growth, including providing more freedom to local authorities to make use of additional revenues to drive forward economic growth in their areas.

The guidance on use of Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) and its application has been clarified to somewhat in the Localism Bill, but there is still some way to go on developing a deliverable solution. In particular, how to use a potential future income flow to secure capital.

Similar principles apply to Tax Increment Financing (TIF). TIF is proposed as a scheme allowing local authorities to borrow against a future uplift in business rates and potentially other wider local taxes. This capital could be used to fund key infrastructure and capital projects.

Under existing arrangements, non-domestic rates (or business rates) revenue collected by local authorities is pooled for redistribution to local authorities in England.

So while local authorities have a vital role to play in supporting the local economy, there is limited direct fiscal incentive to do so. The Government has been considering changes that could provide a much stronger incentive to Councils, particularly through the business rates regime.

These three initiatives are important parts of a wider package of initiatives to encourage local growth and enable future economic growth and development.

In determining the affordability of borrowing for capital purposes, local authorities currently take account of their income streams and forecast future income. However, at present, this does not factor in the full benefit of growth in local business rates income. TIF will enable them to borrow against future additional uplift within their business rates base. Councils can use that borrowing to fund key infrastructure and other capital projects, which will further support locally driven economic development and growth. They will need to manage the costs and risk of this borrowing alongside wider borrowing under the prudential code.

TIFs provide another mechanism for securing finance and without many other options open to local Government, Councils will be investigating whether a TIF could be a solution in their regeneration districts. Over and above the ability to implement TIF will be a need to manage and deliver the process. This is where private sector intervention will be important and presents an opportunity. Where land is in the public sector or in a developer's control, there will be increased enthusiasm to deliver redevelopment and ensure that the schemes are let and ultimately that the TIF model is deliverable

Case study 3

In late 2009, Bournemouth Borough Council was in the process of procuring a private sector partner for a local asset backed regeneration company (LABV) which the Council intends to use as the delivery mechanism for its regeneration initiative known as the "Town Centre Master Vision (TCMV)". The LABV partnership is based on the concept of combining public sector land assets in the town centre with private sector funding and skills. This will enable the Council to meet some of its TCMV objectives whilst allowing the parties to generate an appropriate financial return from development activity, including long term value generation. We have been advising Morgan Sindall Investments Ltd, who last year, were selected as preferred development partner

Conclusion

Local authorities are going to have to use their property portfolios much more creatively to generate capital and protect income flows. This comes at a time when their requirements for property will be changing quite dramatically, their role as an enabler of regeneration is being highlighted, and their staff resources are under pressure. The private sector has a key role in all of this and there will be many different types of opportunities to work with authorities to extract value from an authority's property portfolio. There is no one fixed solution, and new ones will evolve. This is fertile ground for those who understand the sector and the regime local authorities work within.