- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Privacy and Employment and HR topic(s)

- in Asia

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit industries

QuickTake

Like the financial services firms they supervise most financial services supervisory authorities, whether it is the national competent authorities (NCAs) or the European Central Bank (ECB), acting in its role at the head of the Banking Union's Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), have largely returned to a greater degree of office-centric working.

With this welcome end to lockdowns, the ECB-SSM, its peers at the other EU-level authorities (EBA, ESMA and EIOPA) as well as staff at the NCAs are returning to an outlook for a more normal supervisory cycle. This includes a return to picking up the pace in conducting on-site inspections (OSIs) and internal model investigations (IMIs) during 2023 and beyond.

This Client Alert revisits the ECB-SSM's 2018 Supervisory Guide to OSIs and IMIs (the OSIIMI Guide).1 This supervisory guide has not been updated since it was first published in September 2018. 2 While supervisors are likely to put in place some of the health and safety measures perfected during the pandemic, the OSIIMI Guide is important as it marked a major harmonisation and equally a "Europeanisation" of the supervisory toolkit that the Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs) of the ECB-SSM and NCAs applied to both Banking Union supervised institutions (BUSIs) 3 but also the wider body of "inspected legal entities" (ILEs) that are in scope of the OSIIMI Guide.

The OSIIMI Guide forms part of the SSM's supervisory examination programme (SEP) and thus sets strict supervisory expectations of BUSIs and ILEs during inspections but also with respect of supervisory findings. Findings are represented in a ratings grid (F1 to F4) representing the severity of the impact of a finding that then require remediation.

Crucially, the OSIIMI Guide (in its current version) does not contain specific measures for inspections that take place outside of an office centric working environment. It remains to be seen whether the ECB-SSM will introduce such specific measures and if so, whether it will either amend or revise the OSIIMI Guide.

The OSIIMI Guide marks a further "Europeanisation" of the supervisory toolkit and has extraterritorial application

In the context of the OSIIMI Guide's original publication, the ECB-SSM confirmed it was conducting approximately 300 "inspections" a year with respect to the ca. 125 credit institutions directly supervised by the ECB at the head of the SSM.4 In order to cope with this demand, the ECB-SSM has steadily increased its set of dedicated resources to carry out OSIs and IMIs but also when carrying out other industry wide but also more targeted "thematic reviews" on various topics.

The ECB-SSM led inspections can be distinguished between:

- OSIs – which seek to investigate ILE's treatments of risks, its risk controls and governance; and

- IMIs – which focus on the use and governance of prudential models.

These ECB-SSM led inspections are in addition to a range of similar supervisory tools that NCAs can apply in their own investigations as well as those that are conducted as part of "common supervisory actions". Common supervisory actions are investigations or other forms of supervisory reviews often coordinated by one of the EU-level authorities coordinating respective NCAs in the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS).

Crucially, the OSIIMI Guide's publication in September 2018 extended the remit from BUSIs to include ILEs that could be subject of inspections or subject to requests for information. Specifically, this means to include:

"Third-parties to whom credit institutions have outsourced functions or activities, and any other undertaking included in supervision on a consolidated basis where the ECB is the consolidating supervisor."

This can include non-banking financial intermediaries who are regulated financial services firms but in theory, given the wide drafting of the wording, could also include non-regulated firms as well. For some BUSIs and ILEs, the OSIIMI Guide's provisions may sharpen the supervisory tone of engagement beyond what they may have been used to.

Moreover, the ECB-SSM has over the years also stepped up its international coordination efforts on how and when to conduct inspections and with respect to whom. International coordination efforts are also important when considering that the OSIIMI Guide is drafted to apply to BUSIs and ILEs in:

- Banking Union Member States (21 out of 27 EU Member States);

- Non-Banking Union Member States (remaining 6 out of 27 EU Member States) largely through mutual cooperation as part of the ESFS; and

- Third-countries i.e., non-EU jurisdictions, largely through mutual cooperation through various agreements.

What firms should consider when complying with the OSIIMI Guide

The OSIIMI Guide is composed of three sections detailing:

- a "General Framework";

- the "Inspection Process"; and

- applicable "Principles for Inspections".

The legal basis for the aforementioned sections are contained in the founding legislation of the SSM and the CRR/CRD IV regime, along with the provisions of the SSM's internal non-public as well as the public version of the SSM's "Supervisory Manual". The latter details the processes and apportionment of responsibilities within the SSM and the interactions between the ECB's centralised SSM functions and those at the individual NCAs.

It should be noted that since publication of the OSIIMI Guide in 2018, the ECB-SSM embarked in July 2020 on a comprehensive reorganisation of its institutional set-up. It also embarked on targeted recruitment and upskilling efforts, notably with respect to its OSI and IMI teams. 5 Equally, on 2 March 2021, the ECB-SSM published its Guide on Setting Administrative Pecuniary Penalties (SAPP Guide) that may be applied for identified breaches.6

The OSIIMI Guide has not been updated to account for such additional publications and developments so readers should ideally take note of this when considering how inspections under the OSIIMI Guide are carried out.

Summary of key principles in Section 1 – the General Framework

Section 1 of the OSIIMI Guide details the tasks of the SSM's individual decision makers in an inspection process. This includes the roles of the Supervisory Board, the responsibilities of the inspection teams as well as the JSTs, the tasks of the JST Coordinator (JSTC) along with the Head of Mission (HoM) and the approach to be applied when finalising the SEP as well as conducting OSls and IMls so that these conform with the SSM's supervisory objectives. Inspection teams can be comprised of ECB inspectors, supervisors employed by NCAs, JST members as well as, where merited, external consultants.7

The SSM's supervisory objectives aim to ensure that inspections are carried out on a risk-based, proportional, intrusive, forward looking as well as action-orientated manner. The HoM and the inspection team operate independently of, but in coordination with, the JST to ensure that the supervisory objectives are met. The final report following an inspection, and any supervisory expectations contained therein, are to be considered by the JST in its own wider on-going supervisory work. This means that an inspection team's findings may influence the work of the on-going supervision carried out by the JST as well as other non-Banking Union supervision conducted by NCAs. 8

Summary of key principles in Section 2 – The Inspection Process

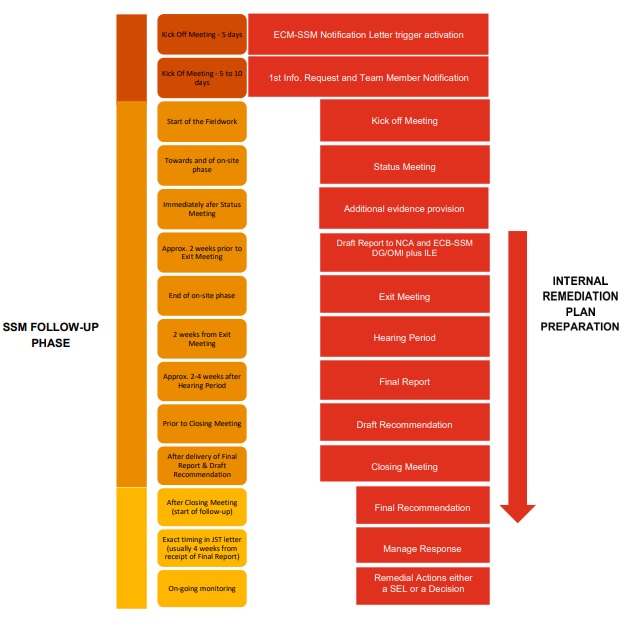

Section 2 of the OSIIMI Guide sets out the individual main steps during an inspection. These can be visually summarised as follows and are discussed in further detail below.

These steps include:

The "Preparatory Phase" includes:

- Notification of an inspection to the ILE sent via a "notification letter";

- First request for information addressed to the ILE;

Ultimately this phase focuses on planning of the entire inspection. During such period an ILE will want to take internal steps to prepare to respond to areas that will come under scrutiny of the investigation phase. The final version of the OSIIMI Guide also (unlike the draft) includes a concept of an "Inspection Memorandum". This document allows the HoM and the JSTC to set the rationale, scope and objectives of an inspection as well as setting of tasks assigned to inspection team members.

The "Investigation Phase" can be broken down into the following steps:

- Holding of a "Kick-off Meeting", which is used to expand the details that had been presented to the ILE in the notification letter and to communicate the objectives, scope and steps involved in the inspection. The OSIIMI Guide is clear in the expectation that ILEs are expected to have senior management engaged and accountable at these meetings;

- Conducting on-site fieldwork by the inspection team;

In the context of the Investigation Phase, Section 2 of the OSIIMI Guide specifically sets out, what it terms "...a wide variety of inspection techniques..." that may be applied by the inspection team for both on-site investigation and off-site review work. These include any of the individual or a combination of the following techniques:

- Observation, information verification and analysis: which aims to check and evaluate the information provided by the ILE and to observe the relevant processes;

- Targeted interviews or requests for explanations orally or in writing: by meeting with the ILE's relevant staff, the inspection team collects information about inspected areas and compares the documented processes and organisational structures with the practices of the ILE, which the inspection team may challenge the interviewees. "Significant interviews" with ILEs must be conducted by at least two inspectors;

- Walk-throughs: whereby the inspection team meets with relevant staff and ensures that the process that the ILE reports is actually embedded and applied in practice. The process aims to also evaluate consistency of provisions and locating gaps and weaknesses;

- Sampling/case by case examinations: allow the inspection team to take targeted or random samples of data or datasets to validate the results and also to gauge the level of problems in certain areas or across the business. This may include but is not necessarily limited to a quality review of the ILE's risk management and efficacy of other governance and control functions. The inspection team will share the methods of data extrapolation with the ILE;

- Confirmation of data: which involves the checking of integrity, accuracy and consistency of the ILE's data by various recalculation and benchmarking means; and

- Model testing: which includes the ILE testing performance of its models and their output using scenario analysis with various hypothetical and historical market conditions dictated by the SSM.

During this phase ILEs will want to ensure that they cooperate with the inspection team but equally at the same time ensure certain safeguards are maintained. This may require an active involvement from various control functions at the ILE (compliance, risk, governance, internal audit as well as legal).9

The "Reporting Phase" will include:

- The inspection team holding an "Exit Meeting" based on a "Draft Report" which has been previously shared with the relevant NCAs and ECB-SSM DG/OMI (i.e. the Directorate General - On-site and Internal Model Inspections – the former DG MS IV prior to the July 2020 reorganisation of the ECB-SSM) prior to being sent by the HoM along with a standardised feedback template to the ILE. This takes place prior to the Exit Meeting where the ILE has a first possibility to comment on the Draft Report;10

- Publication of "Final Report" should occur within two weeks of the Exit Meeting. The HoM, taking on board any relevant written comments (if any) following the feedback (if any) at the Exit Meeting is then responsible for finalising the draft in the Final Report and sending it to the ILE, and possibly the parent entity, if within a supervised group of BUSls, along with a letter of action/supervisory communications;

This phase is arguably the most compact in terms of collating findings, producing reports and communicating them to the ILEs. It also marks a key step forward for the ILE to begin focusing on remediation efforts that follow in the next and final phase of an inspection.

The "Inspection Outcomes Phase" is comprised of:

- Closing Meeting – which marks a capstone in the process; and

- A final deliverable from the ILE in providing its "Draft Action Plan" setting out remedial steps. The Draft Action Plan is then followed by a "Final Action Plan", which may then lead to further follow-up by the JST on the basis of the ILE's Final Action Plan.

In addition to the timeline set out above, the OSIIMI Guide clarifies that the ILE's team has the possibility, "within reason", to request status meetings with the SSM's inspection team. In practice, status meetings are set- up throughout the OSI/IMI as these can aid the work of the inspection team. Status meetings are usually an appropriate forum to discuss/clarify facts and outstanding questions and/or to agree on additional deliverables. These meetings are usually scheduled by the inspection team despite the ILE being able to request them.

In summary, the various phases in an inspection may require some ILEs to revisit their internal procedures to ensure that any deliverables and notably action plans requested from them are prepared presented and executed in a timely manner. This also might merit ILEs to carefully consider when and on what basis to retain support from professional advisors and/or external counsel to draft such deliverables and/or action plans or to protect an ILE's legitimate interests (including where relevant and applicable under national law, on a privileged basis) during the various stages and ultimately in respect of supervisory communications (Recommendations/Decisions – as discussed below) which follow.

The importance of the Final Report and setting of a remedial action plan

Following the conclusion of an inspection, the SSM will provide the ILE with its Final Report along with a draft "Recommendation" or "Decision". The Final Report collates the findings from the investigation and assigns categories to each based on their potential or actual impact on the ILE's financial situation, its level of own funds or own funds requirements. These impact ratings range from "F1" - low impact to "F4" - very high impact.

This categorisation approach or "severity grid" is important and has an operational impact, especially where BUSls may have different assessments or methodologies to that of the ECB-SSM in assessing severity. If for example the ECB-SSM allocates a F3 finding that internally in an ILE would have considered to be F4, the ILE will need to decide whether to use the ECB-SSM rating (which would make reporting obligations more standardised) or use a dual system both for monitoring and remedy. Many larger BUSls maintain a mechanism to encourage lower severity findings and reward improvements to severity findings.

In addition to the Final Report, the SSM will detail the expected remedial actions that the ILE should put in place through a supervisory communication. This can take two forms, namely:

- a letter communicating supervisory expectations in respect of all or only some findings (Supervisory Expectations Letter or SEL) which is an SSM operational act and is thus not legally binding (but nevertheless persuasive) and thus does not require a supervisory "Decision" (see below). In the event of a SEL being issued, the OSIIMI Guide states that the ILE recipient does not receive a formal right to be heard to appeal against the SSM's recommendations set out in the SEL. A recipient of a SEL is only required and expected by the JST to remediate those points raised in the SEL and the Final Report only as it does not contradict the SEL itself. If points in the Draft/Final Report are omitted in the SEL then this may permit a lesser scope of remedial action to be carried out; or, in the alternative

- a formal supervisory Decision11 setting out legally binding supervisory measures addressed to the ILE. The ILE has a right to be heard in respect of a Decision.

The SSM in sending its supervisory communication to the ILE, in particular in the context of issuing a Decision, may exercise other supervisory powers. These may include imposing any of the following on the ILE:

- Conditions: These suspend the legal effectiveness of the ECB-SSM's authorisation or change or extend an internal model until the ILE has taken specific remedial action to comply with its on-going regulatory compliance obligations;

- Limitations: These restrict, prohibit or modify the use of a model and may include a change to how an ILE calculates its own funds requirements, which would cause it to need to raise regulatory capital immediately;

- Obligations: These introduce remedial actions on the ILE in order to restore compliance with its on-going regulatory compliance obligations; or

- Recommendations: These set remedial actions upon the ILE and which, whilst not legally binding, are sufficiently persuasive for an ILE to comply with the communicated recommendation.

Depending on circumstances, the supervisory communication process may also be capped with a "Closing Meeting".

Given the variety of tools that are used by the SSM in its supervisory communications, a number of BUSls have experienced some difficulties as to how to internally manage their deliverables towards the supervisors, as the granularity of and differentiation between these tools is not always fit for purpose in the context of some BUSls' complexity and size.

Moreover, timing is also often an issue. A Draft Report and any draft recommendations may see 6 to 9 months elapsing prior to progressing to the Final Report and Remediation Phase stage. Moreover, timing may also mean that remediation may not be in line with the JST's feedback. It remains to be seen whether this will improve as part of a more normalised supervisory cycle.

Further complexity may often arise in the context of use of language (English v non-English drafted communications) as well as inconsistent use of terminology during the various phases of an inspection and what this might mean for an ILE's remedial action plan and, once executed, whether it is to the satisfaction of the ECB-SSM.

Summary of key principles in Section 3 – "Principles for Inspections"

While the first two sections of the OSIIMI Guide set out the framework applicable to the process of how inspections are conducted, Section 3 sets the tone of how the SSM's inspection teams, the HoM and the JSTC should approach and then discharge their tasks. Section 3 also clarifies the standards of behaviour expected of ILEs during and following an inspection. This also includes how the SSM perceives its own rights vis-à-vis ILEs and ILE's rights against the SSM, including right of recourse that may end with adjudication with the ECB-SSM's Administrative Board of Review and/or the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

Some of the ECB-SSM's powers and principles should be familiar to many BUSls and ILEs. Some may also exist in more prescriptive detail in certain jurisdictions yet some in Section 3 are amended specifically for how the SSM operates. Some BUSls may however find that the interaction with inspection teams might be completely different to what they have been used to with NCA-led investigations and this may prompt a need for adjustments in how such BUSIs approach supervisory dialogue.

These Principles for Inspections aim to remind ILEs:

- to cooperatively work together with the inspection team to ensure the proper conduct and efficiency of the inspection and that ILE's internal rules and policies should not be misused to interfere with this goal;

- that inspection teams may, within the scope of the inspection, conduct all necessary investigations of any persons and thus request any information, explanation or justification and thus be able to obtain and check every document it requires of whatsoever nature and to take copies and extracts. The OSIIMI Guide makes no explicit nor implicit mention of applicable rules and principles of legal privilege that may operate even when dealing with a supervisory authority – even if such rights exist albeit they may also differ per jurisdiction or as a result of specific facts. Furthermore, the OSIIMI Guide remains silent on the SSM's expectations of ILE's internal processes and timeliness to provide information; however, most of the inspection teams try to be mindful of ILE's complexity when requesting information. Nevertheless, it should be noted that any unreasonable delays or failure to provide timely data/information risks being addressed in a non-favourable manner in a Draft or Final Report; and

- that an inspection team has the right to interview any person, regardless of their seniority, and may request the cooperation of qualified staff of the ILE. The OSIIMI Guide does not acknowledge that such person may have rights to be accompanied or represented by inter alia legal counsel in such circumstances – again this may differ depending on facts and circumstances relating to the person and the relevant jurisdiction.

These Principles for Inspections also aim to remind SSM inspection teams of the need:

- to act in an ethical and professional manner, in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and professional procedures and to observe professional secrecy; and

- to respect the rights on which language must be used during an inspection.

Language matters for a number of reasons during an OSI, an IMI or indeed any form of supervisory investigation or an engagement. Language barriers, whether due to linguistic abilities of SSM and/or ILE staff or errors in translation can lead to a number of unintended supervisory outcomes occurring. That being said, the OSIIMI Guide permits ILEs to waive the right to receive a report in a given national language without prejudice to the ILE's future rights as to what language it chooses to use when interacting with the SSM. Importantly, Draft Reports and Final Reports as well as any accompanying supervisory communications are always drafted in English along with, if so requested, an official translation in another national language. In many instances it is prudent to compare the official translation with the binding English language document to ensure it is free form errors and that concepts as well as areas of particular emphasis are expressed in the same manner.

Outlook

The OSIIMI Guide has built an entire new chapter in how the Single Rulebook for financial services in respect of OSIs and IMIs is applied within the Banking Union. This is welcome in terms of driving consistency and certainty for BUSIs and the wider set of ILEs as well as financial services firms more generally notably if the ECB-SSM's efforts are rolled-out by other NCAs. However, the strict supervisory tone and more intrusive level of scrutiny, as, post-pandemic, the SSM reverts to more use of OSIs and IMIs, may require firms to ready themselves for a range of inspections ahead.

Footnotes

1 Available here.

2 Although much of the content of the final OSIIMI Guide was comprehensive overhaul of the previous draft version of the guide that the ECB-SSM had put out for consultation during 2017. A Feedback Statement (available here) was published alongside the final OSIIMI Guide setting out the rationale and context for changes that made it into the final version. Crucially the Feedback Statement also provided details of how the ECB-SSM will use external consultants as part of its OSIs and IMIs. It also provided information on the SSM's improvements to team management and steering, the introduction of better inspection planning principles as well as report preparation. The Feedback Statement concluded with setting out how the SSM will approach multi-agency/multi-jurisdictional cooperation, including with non-EU jurisdictions.

3 This includes those BUSIs that, for Banking Union purposes are categorised as:

- "significant credit institutions" (SCIs) who are subject to lead supervision by the ECB-SSM; and

- "less significant institutions" (LSIs) who are subject to direct NCA-led supervision and only indirect ECB-SSM supervision.

Although the FAQ that was published alongside the OSIIMI Guide stated that the guide will only apply to LSls where the ECB decides to make use of its powers to supervise the relevant LSI directly. Even if this is to be the case, it is quite conceivable that the OSIIMI Guide will be followed by relevant NCAs in the Banking Union in relation to inspections of LSls, as the general practice amongst the various NCAs is to align and apply the ECB-SSM guidelines and standards (incl. those still in draft and/or marked as non-binding) as far as possible when exercising their own powers.

4 One contributing factor to those figures were the completion of the SSM's multi-annual "targeted review of internal models" (TRIM) exercise.

5 See in particular page 15 of "Navigating 2022: a focus on EU as well as Banking Union and Capital Markets Union Supervisory Priorities in the year ahead" published by PwC Legal's EU RegCORE. While this reorganisation is now largely completed, the process of upskilling a growing group of staff assigned to inspection teams as well as JSTs.

6 Available here. Please also see dedicated coverage on this development from PwC Legal's EU RegCORE.

7 In Sections 1.6 and 1.7 of the OSIIMI Guide clarifies that external consultants are considered "as regular team members during the inspection." as well as going on further to state that "External firms are contractually obliged to comply with the ECB's strict professional secrecy requirements. They and their staff are required to sign individual confidentiality agreements to that effect.

8 Yet this coordination is only as efficient as institutional constraints are limited across NCAs and other members of the ESFS. A number of BUSIs, as part of the consultation process leading up to the final publication of the OSIIMI Guide, had stated that in certain instances a more efficient and balanced supervisory engagement process including information sharing amongst authorities would avoid duplication and disruption especially across "business as usual" compliance workstreams. Some BUSIs have experienced difficulties with progressing certain "change" initiatives and/or remediation activities as the information-flow across the larger JSTs and across authorities is not always timely/transparent. This is especially the case where the NCAs in the Banking Union are separated from their conduct of business supervisory counterparts at the national level and problematic where a number of Banking Union supervisory priorities require a high degree of conduct of business input.

9 The OSIIMI Guide makes no mention of an ILE's right, pursuant to EU and/or applicable national law, to be represented by or have legal counsel present in inspection proceedings nor any right to asset legal privilege.

10 The Draft Report is processed within the ECB and with the NCAs for consistency - as opposed to validation. Translation from English into another EU language is undertaken where the ILE has requested to be addressed in their national language as opposed to English. The "Exit Meeting" may also already communicate details on any draft Recommendations or Decisions (see below). Unfortunately, draft Recommendations and/or Decisions may, depending on fact-specific circumstances, diverge from the Final Report's conclusions.

11 i.e., an ECB legal instrument approved by the Supervisory Board

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.