On 12 September 2011, the International Chamber of Commerce ("ICC") published long-awaited revisions to its arbitration rules (the "Rules"), which had been last revised in 1998. The revised Rules are effective as of 1 January 2012 and will apply to any ICC proceedings commencing on or following that date, unless the parties agree otherwise.

The ICC's International Court of Arbitration was established in Paris in 1923 (the Secretariat of the ICC Court opened a branch office in Hong Kong in 2008). There is little question that the ICC is the best known and most global arbitration institution; it administers hundreds of arbitrations taking place across the globe each year. In 2010, the ICC received nearly 800 new cases, involving parties from nearly 140 countries, and seated in more than 50 countries. The ICC also publishes Rules of Expertise, Rules of Conciliation, and Rules for a Pre-Arbitral Referee Procedure, and its revised arbitration rules have been published together with its 2002 ADR Rules.

The revision of the Rules of Arbitration has taken place over the past two years and involved a 20- member drafting committee and a task force drawn from the ICC Commission on Arbitration, and was subject to comments from members of the ICC worldwide. (The revision of the ICC Rules follows recent revisions to the UNCITRAL Rules of Arbitration and the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration, which are discussed in more detail in the linked materials.)

The revised ICC Rules introduce changes intended to reflect current practices in international arbitration. They are also intended to improve transparency and clarity in the process, and to help address concerns about timeliness and efficiency in the arbitral process. The revisions to the ICC Rules are comprehensive and affect the majority of the 41 Articles comprising the Rules. The changes are both large and small, and range from the introduction of new mandatory procedural requirements to revising language of the Rules to reflect gender neutrality (a tribunal is now led by a "president" rather than a "chairman") and changes in technology and methods of communication.

These amendments and additions to the 1998 ICC Rules include:

a. changes to mandatory procedures, including requiring claimants to provide the "basis" for their claims in the Request, requiring a case management conference early in the process, and requiring the tribunal to inform the parties at the close of the proceedings of the expected timing of the award;

b. measures designed to enhance the ability of the parties and tribunal to act expeditiously, including codifying the requirement that an arbitrator provide a statement of availability and an Appendix providing "case management techniques";

c. a detailed provision for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator to decide on urgent conservatory or interim measures;

d. expanded rules addressing issues of multiple parties, multiple contracts and consolidation, which are set out in a separate Article; and

e. express reference to confidentiality orders.

Some of the most significant and noteworthy revisions to the ICC Rules are summarized below. We also include a chart listing optional aspects of the ICC Rules, highlighting aspects of the revised Rules that parties may want to expressly address in drafting arbitration agreements.

A. The ICC's Supervision of the Arbitral Process Under the ICC Rules

One of the distinctive aspects of the ICC International Court of Arbitration and its Rules of Arbitration is the structure of the institution and the roles that various parts of the ICC play in the administration of proceedings under its rules. Under the ICC Rules, the ICC Court plays an important (and mandatory) supervisory role, particularly with regard to important issues such as making an initial jurisdictional determination, appointing arbitrators, deciding challenges to arbitrators, scrutinizing draft awards and fixing the costs of the arbitration. The Rules also provide a role for a Secretariat, led by a Secretary General and including teams of counsel, who are assigned to each case based on geographic criteria and help administer the rules and procedure.

It is important, however, to distinguish between the role of the ICC Court and Secretariat, on the one hand, and the role of the arbitral tribunal appointed by the ICC to decide a particular case, on the other. It is a basic aspect of international arbitration that arbitral institutions such as the ICC (and its organs, including the ICC Court and Secretariat) do not decide a dispute.

Rather, the institution provides the rules and administrative support for the proceedings. The arbitrators appointed by the institution are independent from the institution and actually decide the dispute. The revised Rules make some changes intended to enhance the functioning of these bodies, but do not fundamentally alter their roles in administering cases under the ICC Rules. Moreover, the ICC has taken steps in the revised Rules to underscore that the ICC itself is the only institution authorized to administer arbitration under the ICC Rules, and, arguably, to protect the integrity of its rules and its brand.

In particular, the revised Rules respond to the use of "hybrid" arbitration clauses, in which parties agree to arbitration pursuant to the ICC Rules, but with the provision that the arbitration will be administered by an arbitral institution other than the ICC. In the best known recent example, in the case of Insigma Technology Co Ltd v Alstom Technology Ltd [2009] SGCA 24, the Singapore Court of Appeal upheld the validity of a hybrid arbitration clause which required the Singapore International Arbitration Centre ("SIAC") to administer an arbitration using the ICC Rules.

In response to such hybrid proceedings, the ICC has added wording to Article 1(2) of the revised Rules declaring that the ICC Court "is the only body authorized to administer arbitrations under the Rules, including the scrutiny and approval of awards rendered in accordance with the Rules." The ICC also has included language in Article 6(2), which addresses the "Effect of the Arbitration Agreement," that states that "by agreeing to arbitration under the Rules, the parties have accepted that the arbitration shall be administered by the [ICC] Court." According to the ICC, these clarifications are intended to protect the integrity of its Rules, avoid potentially pathological arbitration clauses, and avoid potential difficulties in the enforcement of awards. The effect of these provisions on hybrid clauses providing for administration by institutions other than the ICC remains to be seen.

B. Expanded Scope of the ICC Rules

While the great majority of the cases administered by the ICC involve commercial disputes, there has been a dramatic increase in the last decade in investor-State (or treaty) arbitrations, in which a foreign investor brings an arbitration claim against a State under the authority of a bilateral investment treaty or multilateral investment or trade agreement. A number of treaties authorize an investor to institute a treaty claim against a State pursuant to the ICC Rules. According to ICC statistics, approximately 10% of the ICC's cases in 2010 involved a State or para-statal entity, and these include a number of treaty claims. In recognition of the growth of cases involving treaties and State parties, the ICC has deleted the language in the previous versions of the Rules – which provided that the "function of the [ICC] Court is to provide for the settlement by arbitration of business disputes of an international character" – and in its place, revised Article 1(2) uses the broader term "disputes," with no suggestion of any limitation as to the type of disputes the ICC Court administers.

C. More Robust Requirements at the Commencement of Arbitration

The revised Rules include a number of changes aimed at improving the information provided at the start of the proceedings, such as more expressly requiring claimants and counterclaimants to include information at the outset of the proceedings on the basis for their claim(s) and counterclaim(s), and the amounts in dispute.

Basis for Claim. In particular, the revised Rules include new language concerning the nature and amount of information a claimant is required to include in a Request for Arbitration. The revised Rules now require a claimant to identify counsel, if any, representing it, and to provide information regarding the basis of its claim(s). Where Article 4(3)(b) in the 1998 Rules required only "a description of the nature and circumstances of the dispute giving rise to the claim(s)," Article 4(3)(c) in the revised Rules requires that a claimant must include the "basis upon which the claims are made."

Similarly, Article 5(5) now requires a respondent who asserts a counterclaim to include the "basis upon which the counterclaims are made." As with a number of other revisions, it is not clear how much of an impact the revised language will have in practice, but the revision promotes the principle that the more clarity the parties and the tribunal have at the early stages of proceedings about the nature of the dispute, the better the opportunity to agree to a focused and appropriate procedure and more efficiently resolve the dispute in a timely manner.

Amount in Dispute. The revised Rules also include more expansive language concerning the amount of information that a claimant should provide in the Request for Arbitration concerning the amount in dispute. Article 4(3)(d) in the revised Rules is intended to provide greater clarity from the start, requiring a claimant to provide the amounts of any quantified claims, and "to the extent possible, an estimate of the monetary value of any other claims." Previously the Rules required only "an indication of any amount(s) claimed," which led to criticism that claimants could fail to quantify the amount in dispute or include a small amount of damages in the Request for Arbitration, only to substantially upwardly revise the damages later in the proceedings. Article 5(5) provides a similar requirement for respondents asserting a counterclaim.

The more stringent language regarding the obligation to identify the amount in dispute early in the proceeding has a number of potential benefits. Among other practical consequences, the advances paid by the parties to cover arbitrators' fees and to fund the ICC's administrative costs are based on the amount in dispute. More generally, greater clarity about the amount in dispute may be useful in crafting appropriate procedures and timetables, and may also help facilitate settlement.

D. Impartiality and Availability of Arbitrators

The revised Rules include amended disclosure requirements for arbitrators. Where previously an arbitrator was required to provide a "statement of independence" before being appointed, the new Article 11(2) requires an arbitrator to provide a statement of "acceptance, availability, impartiality and independence."

Availability. This new provision codifies in the revised Rules a practice that has been in place at the ICC for the past several years (but was not expressed in the 1998 Rules), and responds to criticisms that one of the factors that contributes to delay in proceedings is arbitrators who may be over-extended or otherwise unable to devote the time needed to move a case forward expeditiously. The existence of the availability statement should also enhance the ICC's ability to select appropriate arbitrators and to monitor their performance.

Impartiality. The ICC has also revised the language concerning arbitrator independence to bring the ICC standard in line with the terminology used by many other institutions and in many national arbitration laws. The revised Rules now expressly require that an arbitrator be "impartial and independent." In his or her statement of acceptance, availability, impartiality and independence, an arbitrator is also now required to disclose "any circumstances that could give rise to reasonable doubts as to the arbitrator's impartiality." This reference to "impartiality" appears throughout the revised Rules wherever the Rules previously referred to independence.

E. Emergency Arbitrator

Under all leading arbitration rules, a tribunal generally has the power to grant conservatory or interim measures. One issue that arises, however, is that a party may perceive an urgent need for such measures at the outset of proceedings, before the arbitral tribunal has been constituted (and the process of constituting the tribunal may take a number of months). Parties can apply to a court of competent jurisdiction for such measures, but may be reluctant to do so for a number of reasons.

For this reason, a number of arbitral institutions have recently revised their rules to provide parties with the option of a so-called "emergency arbitrator," who can be appointed at very short notice to hear an emergency request for such measures and make an interim order as appropriate. In the last 18 months, for example, among others, the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce ("SCC") and the SIAC have both amended their rules to provide for an emergency arbitrator procedure.

The revised ICC Rules now provide a similar mechanism: Article 29 of the revised Rules allows the parties to request "urgent interim or conservatory measures" to an emergency arbitrator, pending the constitution of the tribunal. The rule is meant to create a temporary solution: although the parties are required to "comply with any order made by the emergency arbitrator," the emergency arbitrator's order is not binding on the tribunal with respect to any request issue or dispute determined in the emergency arbitrator's order.

It is important to note that, pursuant to Article 29(6)(a), the emergency arbitrator provisions do not apply to arbitration agreements that have been concluded before 1 January 2012. Even where the arbitration agreement has been concluded on or after 1 January 2012, the parties are not obliged to accept the emergency arbitrator provision as part of their agreement. They have the right under Article 29(6)(b) to opt out of the emergency arbitrator provision, and the right under Article 29(6)(c) to agree to another prearbitral procedure that provides for the granting of conservatory, interim or similar measures. Furthermore, Article 29(7) clarifies that, even when the emergency arbitrator provision applies, the parties are not prevented from seeking interim or conservatory measures from "a competent judicial authority at any time prior to making an application for such measures ... pursuant to the Rules."

Detailed procedures for the application for emergency measures, the appointment of the emergency arbitrator, challenges to the emergency arbitrator, place for the emergency arbitrator proceedings, the proceedings themselves and any order issued by the emergency arbitrator are set out in Appendix V to the revised Rules.

As set out in Appendix V, the process is designed to last no longer than three weeks from the initial application to the ICC Secretariat for emergency measures up to and including the issuance of any order by the emergency arbitrator.

The Rules also include language designed to address expeditiously any challenge to the appointment of the emergency arbitrator. Article 2(1) of Appendix V provides that the President of the ICC Court "shall appoint an emergency arbitrator within as short a time as possible, normally within two days from the Secretariat's receipt of the Application." Any challenge to the appointment must be made "within three days from receipt by the party making the challenge of the notification of the appointment" (Article 3(1) of Appendix V). Any such challenge will be decided by the ICC Court after the parties and emergency arbitrator have been afforded an opportunity to provide comments in writing "within a suitable period of time" (Article 3(2) of Appendix V). A procedural timetable is to be established by the emergency arbitrator "normally within two days" of the transmission of the file from the ICC Secretariat (Article 5, Appendix V). The "Order shall be made no later than 15 days from the date on which the file was transmitted to the emergency arbitrator," although that time limit can be extended by the President of the ICC Court.

The cost of the emergency arbitration process is significant, even in the context of large disputes. An applicant is required to pay a fee of at least US $40,000 to cover the ICC administrative expenses and emergency arbitrator's fees and expenses, although the President of the ICC Court can decide to increase that amount "taking into account, inter alia, the nature of the case and the nature and amount of work performed by the emergency arbitrator, the [ICC] Court, the President and the Secretariat" (Articles 7(1)-(2) of Appendix V). There is no guarantee that the party applying for emergency measures will recover these costs even if the application is successful: the allocation of costs is left entirely to the discretion of the emergency arbitrator, and will form part of the emergency arbitrator's "Order" (Article 7(3) of Appendix V).

F. Multiple Parties, Joinder and Consolidation

The revised Rules address in more detail some aspects of the difficult procedural issues that can arise where there are multiple parties to a dispute and/or multiple contracts.

The 1998 Rules have a limited mechanism for consolidation of multiple proceedings between the same parties at the early stages of the disputes (i.e., before the Terms of Reference are signed, which must occur within two months of the constitution of the tribunal), but no provision allowing for the joinder of new parties to an arbitration or allowing additional parties to intervene in an existing arbitration. In contrast, the revised Rules include a new section devoted to issues of joinder, multiple contracts and consolidation. Other articles in the Rules have been revised to take into account the possibility of disputes arising between multi-parties to a single contract, disputes arising between the same parties out of several different contracts, and disputes affecting the rights and obligations of third parties. In particular, "additional party" is now defined as one or more additional parties; "party" or "parties" now includes claimants, respondents or additional parties; and "claim" or "claims" now includes any claim by any party against any other party.

Joinder. While there was no express provision in the 1998 Rules for parties that had not been named in the Request for Arbitration to be joined to a proceeding, Article 7 of the revised Rules sets out an express process for joinder of additional parties to an arbitration. It allows such parties to be joined before the confirmation or appointment of any arbitrator, although no additional party may be joined after that point in the process, "unless all parties, including the additional party, otherwise agree." Article 7(1) also confers on the ICC Secretariat the power to fix a time limit for the submission of a "Request for Joinder," which appears intended to prevent any such request from resulting in undue delay in the constitution of the tribunal.

Multiple Contracts. Article 9 of the revised Rules specifically deals with multiple contracts, and permits that claims arising out of several contracts and under several arbitration agreements can be brought in a single proceeding, irrespective of whether such claims are made under one or more than one arbitration agreement under the ICC Rules.

Article 9 is expressly subject to Article 23(4), which limits the parties' right to make new claims once the Terms of Reference have been signed or approved by the ICC Court. If a party wishes to make a new claim after this time, it must be "authorized to do so by the arbitral tribunal, which shall consider the nature of such new claims, the stage of the arbitration and other relevant circumstances."

Parties may not want to have claims arising from multiple contracts heard in a single arbitral proceeding where they have not expressly agreed to do so in their contractual arrangements. In that circumstance, if the parties want to ensure that claims under different agreements cannot be brought together, they may consider opting out of Article 9 when drafting their arbitration agreement, as discussed below in Section J.

Consolidation. Article 10 of the revised Rules provides for the possible consolidation of multiple related arbitrations. In particular, Article 10 notes that "the [ICC] Court may, at the request of a party, consolidate two or more arbitrations pending under the Rules into a single arbitration."

Consolidation is permitted under Article 10 where: (i) the parties have agreed to consolidation; (ii) all the claims in the arbitrations are made under the same arbitration agreement; or (iii) where the claims in the arbitrations are made under more than one arbitration agreement, the arbitrations are between the same parties, the disputes arise in connection with the same legal relationship, and the ICC Court finds the arbitration agreements to be compatible.

G. Cost and Efficiency

One of the ICC's express intentions in revising the Rules is to address concerns about the efficiency of the arbitral process and to encourage cost-effective case management. In that regard, the revised Rules include a number of changes and additions intended to assist the ICC Court in more expeditiously constituting tribunals and to enable and encourage parties and arbitrators to conduct proceedings in an expeditious and cost-effective manner.

1. Constitution of Tribunal

Expedited Consideration by ICC of Jurisdiction. Under Article 6(2) of the 1998 Rules, where there was a challenge to the ICC's jurisdiction at the outset of the proceedings, the ICC Court was required to make a determination that there was a prima facie evidence of jurisdiction. The ICC's statistics show that from 2006 to 2009, in only 3% of the 853 cases submitted to the ICC Court for an Article 6(2) decision on jurisdiction did the ICC Court refuse to allow the case to proceed due to an obvious lack of jurisdiction.

Rather than requiring that all such objections be decided by the ICC Court, the revised Rules introduce a screening process intended to save time and cost and improve efficiency. Article 6(3) of the revised Rules provides that the ICC Secretary General will perform an initial screening function, so that only those jurisdictional challenges that have a significant chance of succeeding will be referred to the ICC Court. Where the Secretary General determines that the jurisdictional challenge has no significant chance of succeeding, the case will be sent directly to the tribunal (which will then make its own decision on jurisdiction as the arbitration proceeds).

ICC Court's Authority to Directly Appoint an Arbitrator. The revised Rules feature another measure designed to speed up the process of constituting the tribunal. Under the ICC's process, where the ICC is required to identify and appoint an arbitrator, the ICC Secretariat asks one of its national committees to do so. Article 13(3) of the revised Rules now grants the ICC Court the power to appoint directly an arbitrator "that it regards as suitable" in circumstances where it disagrees with the proposal of the relevant National Committee, or where the relevant National Committee has failed to make a proposal within the timeframe specified by the ICC Court.

2. Mandatory Case Management Conference

Although many tribunals have adopted the practice of holding a procedural conference with the parties at an early stage of the proceedings to clarify the issues in dispute and identify appropriate procedures, the 1998 Rules do not require such a meeting. Article 24(1) of the revised Rules makes it compulsory for the tribunal to convene a "case management conference."

The case management conference required by Article 24(1) must be convened at the point when the tribunal is "drawing up the Terms of Reference or as soon as possible thereafter." The Terms of Reference (which must also be followed by a provisional timetable) are a unique feature of the ICC Rules. The Terms of Reference are designed to focus the tribunal and the parties on the key issues in dispute at an early stage of the proceedings, by requiring the tribunal to draw up a document containing (among other things) a summary of the parties' respective claims and, if the tribunal considers it appropriate, a list of the issues to be determined. The revised Rules seek to enhance this process by mandating that the parties and tribunal meet in connection with this process.

The purpose of the case management conference is for the tribunal "to consult the parties on procedural measures that may be adopted pursuant to Article 22(2)." Article 22(2) in turn gives the tribunal the discretion to "adopt such procedural measures as it considers appropriate, provided that they are not contrary to any agreement of the parties" for the purpose of "ensur[ing] effective case management." Article 24(1) also notes that the "procedural measures" adopted by the tribunal and the parties "may" include one or more of the "case management techniques" set out in Appendix IV to the revised Rules.

The case management techniques in Appendix IV include a number of common sense and practical suggestions, and generally reflect the ICC's Techniques for Controlling Time and Costs in Arbitration, first published in 2007. This includes, for example, techniques such as: (i) identifying issues that can be resolved by agreement between the parties or their experts; (ii) using telephone or video conferencing for procedural and other hearings where attendance in person is not essential; and (iii) limiting the length and scope of written submissions to avoid repetition and maintain focus on key issues.

3. Tribunal's Authority to Control Proceedings

The revised Rules also include several provisions designed to encourage compliance with the tribunal's orders and provide the tribunal with the express authority to sanction a party which fails to contribute to making the proceedings expeditious and cost-effective.

Cost Consequences for Not Conducting the Arbitration Expeditiously and in a Cost-Effective Manner. Cost shifting is a common feature of international arbitration and the ICC Rules provide that, where the parties have not agreed otherwise, the tribunal has the authority in its final award to fix the costs of arbitration "and decide which party shall bear them or in what proportion they shall be borne by the parties." The revised Rules include language in Article 37(5) providing that, "in making decisions as to costs, the arbitral tribunal may take into account such circumstances as it considers relevant, including the extent to which each party has conducted the arbitration in an expeditious and costeffective manner."

While the tribunal may always have had this authority, the revised language is intended to encourage arbitrators to exercise that authority (and to encourage parties to cooperate in the efficient conduct of the proceedings). The new language in the ICC Rules is similar to recent efforts to expressly underscore an arbitral tribunal's authority to impose costs consequences for parties' conduct in the 2010 revisions to the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration and in the recent LCIA India Rules.

Duty to Comply with Tribunal Orders. The ICC has also added language in Article 22(4) expressly stating that the parties undertake to comply with any order made by the tribunal. While it is not clear whether this language will give a tribunal any greater coercive authority to enforce its orders, the revised language underscores the parties' obligation to participate in good faith in arbitration proceedings.

H. Expected Date of the Award

The ICC Rules require the final award to be issued within six months of the signing of the Terms of Reference, although in practice that deadline is extended by agreement of the parties in many cases. Even where the parties have agreed to an extended timetable, they frequently complain about the length of time it can take to receive a final award after the close of proceedings. In addition to greater transparency about arbitrator availability, one of the ways that the ICC hopes to address concerns about the length of proceedings is through increased transparency about the timing of the delivery of the final award.

In what should be a welcome change, under Article 27 of the revised Rules, at the close of the proceedings, the tribunal is required to communicate to both the ICC Secretariat and the parties the date by which it expects to submit its draft award to the ICC Court. Article 27 also provides a more specific definition of the close of proceedings, providing that the close of proceedings comes after the last substantive hearing or the filing of the last substantive submission, whichever comes later.

Knowing in advance the expected date of delivery of the final award not only means that the parties will have some forewarning that the award is imminent, but it also may be helpful in facilitating possible settlement before the award is issued.

I. Confidentiality Orders

While parties often assume that arbitration is a confidential process, there is no consensus in national laws as to whether arbitration is confidential. Some jurisdictions, such as England, provide for an implied duty of confidentiality, with certain exceptions (e.g., if the disclosure is reasonably necessary for the enforcement of a party's legal rights); other jurisdictions include express confidentiality obligations in their national law, while the law in other jurisdictions is that there is no duty of confidentiality absent agreement by the parties. Similarly, the issue of confidentiality is approached in different ways under different arbitration rules – some arbitration rules expressly provide for confidentiality (e.g., the LCIA Rules) while most arbitration rules are silent, leaving the issue of the parties' duty of confidentiality to the applicable law or agreement of the parties.

While the Rules impose a duty of confidentiality upon the ICC and the arbitrators, neither the 1998 Rules nor the revised Rules impose a duty of confidentiality on the parties.

The revised Rules now address for the first time the issue of party confidentiality. Specifically, in Article 22(3) of the revised Rules, the tribunal is given the express power to make orders "concerning the confidentiality of the arbitration proceedings or of any other matters in connection with the arbitration." The tribunal can make such orders "upon the request of any party."

It is noteworthy that the ICC has rejected the opportunity to insert a default confidentiality provision and parties agreeing to arbitrate under the ICC Rules therefore need to consider whether they should include express confidentiality provisions in their contractual arrangements. Nonetheless, Article 22(3) of the revised ICC Rules gives the parties and the tribunal the opportunity to address the issue and to tailor a confidentiality order that is responsive to the needs of the parties in that particular arbitration.

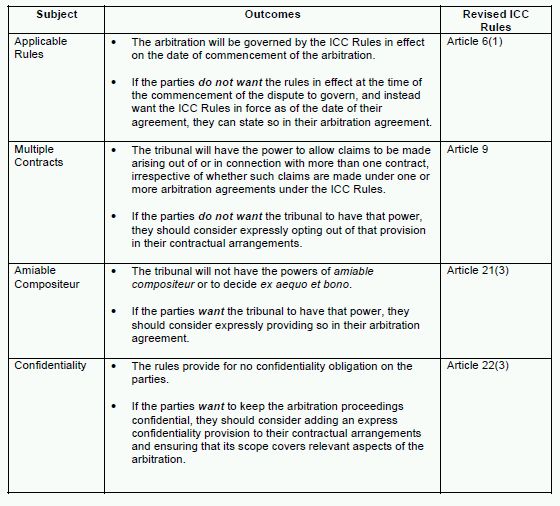

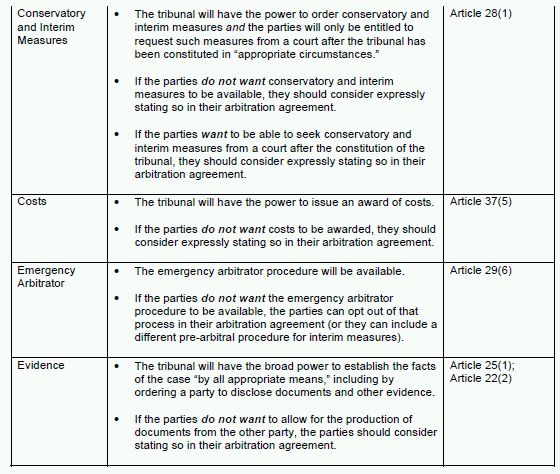

J. Optional Provisions Under the Revised ICC Rules

While certain aspects of the ICC Rules are mandatory, as with the 1998 Rules, the revised Rules still permit opting out of any provision that does not involve the competency of the ICC Court. The chart below summarizes some of the more significant provisions that parties may want to consider opting out of when drafting agreements to arbitrate subject to the revised ICC Rules.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.