STATISTICS

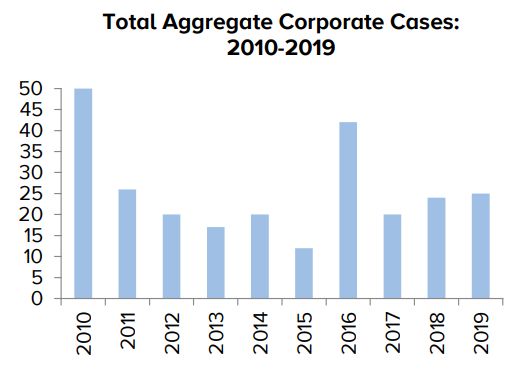

In 2019, the DOJ and SEC resolved twenty-five corporate enforcement actions. Consistent with the trends and patterns over the past years, the DOJ apparently deferred to the SEC to bring administrative enforcement cases in the less egregious matters, which has resulted in the SEC bringing six enforcement actions without parallel DOJ actions and typically with lower penalty amounts. On seven occasions, the DOJ and SEC brought parallel enforcement actions against corporations and one or more of their subsidiaries (Cognizant, MTS, Fresenius, Walmart, Technip, Microsoft, and Ericsson). In keeping with the trend from recent years, a vast majority of the financial sanctions in 2019 resulted from these joint enforcement actions – $2.7 billion out of a total of $2.9 billion. As we discuss in more detail below, these parallel enforcement actions involved wide-spread allegations of bribery and controls failures, often spanning multiple countries and prolonged periods of time.

Regarding FCPA enforcement actions against individuals in 2019, the DOJ charged or unsealed charges against twenty-six individuals, while the SEC brought cases against only five individuals, including three who were also charged by the DOJ.

We discuss the 2019 corporate enforcement actions, followed by the individual enforcement actions, in greater detail below.

CORPORATE ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS

Until shortly before the end of 2019, the matter relating to MTS remained the largest combined penalty against a corporation in 2019. However, in early December, the DOJ and SEC announced enforcement actions against Ericsson, resulting in one of the largest penalties in FCPA history—topping out at $1.06 billion. With increasingly complex settlements, often involving a mix of inter-agency credits and global settlements, there seems to be a lot of debate and inconsistency in how to calculate the "largest enforcement action of all time." We take a "money out the door approach"—netting the payments for credits between the DOJ and SEC but counting payments made to foreign authorities. By this count, Ericsson comes in second behind Petrobras ($1.7 billion). The Ericsson settlement's action's arguably recordbreaking size appears to be attributable to the breadth of the allegations, which spanned five countries and sixteen years, and Ericsson's failure to obtain full cooperation or remediation credit, discussed in further detail below.

In the Statement of Facts, to which Ericsson admitted in the DPA, the DOJ described the following bribery schemes:

- Djibouti. From 2010 to 2014, Ericsson agreed to pay approximately $2.1 million in bribes to Djibouti officials to win a contract to provide services to a state-owned telecommunications company, worth approximately €20.3 million. To disguise the payment, Ericsson made it to a consulting company owned by the spouse of a foreign official and then drafted a due diligence report that did not include the relationship between the consulting company and the official.

- China. From 2000 to 2016, Ericsson engaged in a bribery scheme in China in which it paid about $31.5 million to various third parties, some of which the DOJ states was used to "provide things of value, including leisure travel and entertainment, to foreign officials." The bribery scheme also involved "sham contracts" with these third parties pursuant to which Ericsson made payments for work that was never performed. These payments were also made in contravention of Ericsson's policies, which prohibited the use of third-party agents, except in limited circumstances, since 2011.

- Vietnam. In Vietnam, all of Ericsson's customers were government-owned, making it a high-risk jurisdiction. The DOJ noted that Ericsson paid approximately $4.8 million to a consulting company, which it put into an off-the-books account for a sales agent. The sales agent then passed these funds to other third parties, including agents of Ericsson's governmentowned customers.

- Indonesia. Similar to the conduct in Vietnam, from 2012 to 2015, Ericsson paid about $45 million to a consulting company, which created an off-the-books fund. However, the government did not specifically allege involvement of government officials in this scheme.

- Kuwait. The DOJ claimed that Ericsson paid approximately $450,000 to an official of a state-owned telecommunications company to win a tender, including by obtaining inside information about the tender. Ericsson won the tender, worth about $182 million. In connection with the scheme, the DOJ detailed a communication by an Ericsson employee who was "asked to sort out the mess we got into in Kuwait" and was upset about having to "clean[] it up."

In accordance with these charges, the DOJ charged Ericsson with two counts of conspiracy—one for violations of the anti-bribery provisions and one for books-and-records and internal control violations. Ericsson's Egyptian subsidiary pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions. In total, they agreed to pay a total criminal penalty of $520,650,432. Ericsson also entered into a settlement agreement with the SEC pursuant to which it agreed to pay disgorgement and prejudgment interest totaling $539,920,000.

All said and done, Ericsson's payment will tip just over the $1 billion mark, at $1.06 billion, putting it in a lonely club with Petrobras and Odebrecht/Braskem. Unlike in the Petrobras and Odebrecht/Braskem matters where the penalties were divvied up between the U.S. and foreign authorities, the entirety of this penalty will go to the U.S. Treasury. In this way, Ericsson could lay claim to the largest FCPA enforcement action in which all penalties only went to U.S. authorities. Also, based on media reports, the Swiss authorities are investigating Ericsson for corruption-related offenses, which could result in even larger penalties against the company.

The Ericsson matter certainly has some of the hallmarks expected in a large enforcement action—multiple, long-running violations and controls failure, involvement of several "high-level executive[s]" of LM Ericsson and Ericsson AB, and fairly high dollar values in both the bribes paid and business obtained. However, the matter would not have cracked the $1 billion level if Ericsson had obtained full remediation and cooperation credit, which in most cases accounts for a 25% discount.

According to the DOJ, Ericsson "did not disclose allegations of corruption with respect to two relevant matters, produced certain relevant materials in an untimely manner, and did not timely and fully remediate, including by failing to take adequate disciplinary measures with respect to certain executives and other employees involved in the misconduct." This seems like a pretty serious "what-not-to-do list" for companies trying to earn the cooperation and remediation credit, and perhaps Ericsson was lucky to have obtained even a 15% discount off the sentencing guidelines

In second place and still representing a considerably large settlement not to be overshadowed by late-comers, the MTS enforcement actions, brought by the DOJ and the SEC against Mobile TeleSystems, a Russian telecommunication services provider, its Uzbekistan subsidiary, Kolorit Dizayn Inc., and two related individuals stemmed from an alleged bribery scheme in the Uzbekistani telecommunications market. MTS represents the third FCPA enforcement action involving bribery schemes centered in Uzbekistan around the telecommunications market, after VimpelCom in 2016 and Telia in 2018. According to the DOJ and SEC, MTS made at least $20 million in illicit payments to an Uzbekistani government official from 2004 to 2012 to obtain and retain business. MTS allegedly obtained more than $2.4 billion in revenues from the scheme—which might explain why corporations are willing to engage in bribery to secure access to the lucrative Uzbekistani telecommunications market.

Specifically, MTS allegedly (i) paid an Uzbek company owned by a government official $12 million, $4 million of which went to the government official, to obtain the rights to telecommunications frequencies that would otherwise be unavailable to MTS under Uzbek law; (ii) amended options pertaining to an MTS subsidiary in a manner that benefited a company partially owned by the same government official before buying the company out; (iii) paid a company beneficially owned by the government official $30 million in exchange for its rights to 800 MHz frequencies; (iv) purchased an Uzbek subsidiary from the government official for the inflated price of $40 million after the company had been valued at $23 million; and (v) contributed more than $1 million to charities controlled by the government official, mischaracterizing them in MTS's books and records as advertising and non-operating expenses. As a result of these alleged acts, the SEC alleged MTS violated the anti-bribery, books and records, and internal accounting controls provisions of the FCPA. The DOJ similarly alleged violations of all three provisions of the FCPA.

Notwithstanding the fact that it made admissions in the DOJ matter, MTS resolved the charges made against it by the SEC without admitting or denying the allegations. It agreed to pay a civil penalty of $100 million and retain an independent compliance monitor for at least three years. MTS also entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ in which it admitted the facts alleged against it and agreed to a fine and restitution totaling $850 million. Consistent with the DOJ's policy on coordination of corporate enforcement actions, MTS's $100 million civil penalty paid to the SEC was credited by the DOJ towards its settlement. MTS's subsidiary, Kolorit, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery and books-and-records provisions. It was ordered to pay a $500,000 criminal fine and $40,000,000 in criminal forfeiture (both of which were to be deducted from MTS's total penalty). Notably, the DOJ denied MTS the usual remediation and cooperation credit, giving it no discount from the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines and assigning it a penalty squarely within the range.

To view the full article, please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.