By Seth Bruneel, Stacy Lewis

Introduction

In June 2018, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit heard two cases, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharmaceutical (Docket No. 2017-2173) and Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC (Docket No. 2017-2284). Both cases set forth questions of obvious-type double patenting ("ODP") that arise out of timings relative to the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (hereafter "GATT").1 Both cases present unique issues and provide the Federal Circuit with an opportunity to answer unclear questions from earlier precedent.

Background

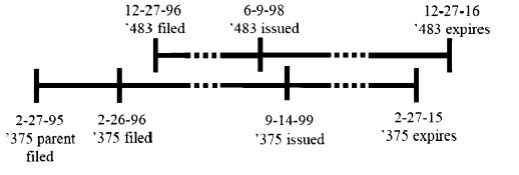

In Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208 (Fed. Cir. 2014), the Federal Circuit addressed whether a later-issued, but earlier-expiring patent could qualify as a double patenting reference against an earlier-issued but later-expiring patent. Gilead brought suit against Natco for infringement based on U.S. Patent 5,763,483 ("the '483 patent"). Natco asserted that the '483 patent was invalid for ODP over Gilead's patent, U.S. Patent 5,952,375 ("the '375 patent"). As shown below, the '483 patent was filed in December 1996, issued in June 1998, and expired in December 2016. The '375 patent claimed priority to February 1995, issued September 1999, and the twenty-year-term expired February 2015.

The Federal Circuit panel (Judges Prost, Chen, and Rader; Judge Rader filed a dissenting opinion) based its decision on public policy reasoning. Gilead argued that the '375 patent did not extend the exclusivity of the '483 patent, grabbing onto the idea that double patenting can be a bar to a second issued patent based on a first issued patent, but not vice versa. However, the majority of the Court set aside the fact that the '483 patent issued first, focusing instead on expiration dates and the policy idea that at the expiration of a patent, the public has a right to use the invention claimed.

The Court in Gilead explained that the expiration date "guarantees a stable benchmark that preserves the public's right to use the invention ... when that patent expires."2 Thus, the Court, on the facts before it, held that a patent that issues after, but expires before, another patent can qualify as a double patenting reference for the previously-issued, later-expiring patent if the claims of the two patents are not patentably distinct.

Later that same year, the Federal Circuit decided Abbvie Inc. v. Mathilda & Terence Kennedy Inst. of Rheumatology Trust, 764 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2014). Abbvie answered the question of whether the doctrine of ODP still applies in light of GATT. The Court in Abbvie upheld ODP where two patents were admittedly directed to claims that were not patentably distinct but had different expiration dates. Abbvie, 764 F.3d at 1372 (clarifying that for invalidity based on ODP, the alleged infringer bears the burden of proving lack of patentable distinctness by "clear and convincing evidence.").

Ezra

Against this legal backdrop, the Federal Circuit revisits ODP in the Ezra and Breckenridge cases. Ezra addresses whether a second-filed, second-issued patent can be asserted as an ODP reference where the statutorily defined patent terms are different due to pre-GATT and post-GATT status and a patent term extension.

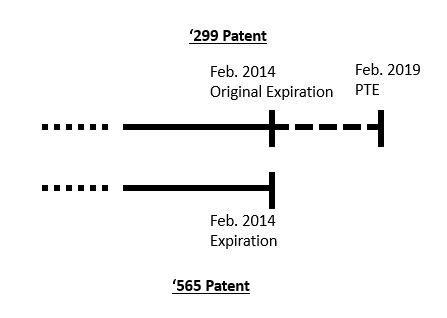

Judge Stark in the District Court of Delaware was not persuaded by Ezra's arguments that the grant of the patent term extension for the '299 patent (see top line below) effectively extended the term for the '565 patent (see bottom line below). Judge Stark relied on the Federal Circuit's analysis of the legislative history for 35 U.S.C. § 156 to decide that Congress left the choice of which single patent term to extend in the hands of the patent owner. Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharma. Co., 482 F.3d 13717, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2007). He further reasoned that this flexibility included the "de facto" extension of the second patent due to patent term extension of the first, as shown below.

During oral arguments in front of Judges Moore, Chen, and Hughes, Ezra argued that the flexibility left to the patent owner in Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharma. Co., 482 F.3d 13717, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2007), does not permit patent term extension to effectively extend a second patent, here the '299 patent. But rather, according to Ezra, the patent owner must make a thoughtful choice as to which patent term to extend under §156. Ezra argued that Novartis made the wrong decision and that a patent term extension is not a period of immunity. Instead, all other patent laws still apply to the '299 patent during the extension, including ODP over the '565 patent.

Novartis argued that ODP is used to stop "unjust" extension of a patent term but that a patent term extension is a justified extension created by Congress and codified in law after Congress weighed public policy considerations.

Novartis also used footnote 6 from the Gilead case to support their arguments. Footnote 6 said that there are exceptions to the pre-GATT rule that later-issued patents expired later, such as in the case of a patent that qualifies for term extension. Gilead, 753 F.3d at 1215. And since the patent term extension was obtained by adherence to the relevant law and procedures, the extension was, according to Novartis, a justified extension.

Weighing the arguments presented and the questions from the Judges, it suggests, even though reading a panel involves guesswork, not mathematics, that the Federal Circuit will uphold Judge Stark and uphold a patent owner's choice of which patent term to extend, even though that choice, in the case of a second-expiring patent as in Ezra, could lead effectively to an extension of a first-expiring patent. The Federal Circuit has already pointed out (Gilead footnote 6) that there are exceptions. Further, Congress has provided a means to extend the term of a patent with the only limitation being that only one patent may be extended.

Breckenridge

The day after the oral argument for Ezra, Judges Prost, Wallach, and Chen (Judge Chen was common to both panels), heard arguments in Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharmaceutical. Breckenridge was appealed from the District of Delaware where Judge Andrews held that a later-filed, earlier-expiring, post-GATT patent could serve as an ODP reference to invalidate a first-filed, later-expiring pre-GATT patent and thus deny that pre-GATT patent from enjoying a full seventeen-year term from issuance.

Judge Andrews distinguished Gilead from this case by pointing out that Gilead involved two post-GATT patents and that the differences in priority were the cause of the differences in expiration dates. Novartis urged that ODP was an equitable doctrine requiring a showing that the extension of the patent term was somehow unjust or that the patent owner had engaged in gamesmanship. However, Judge Andrews disagreed and found that the '990 patent was a proper double patenting reference for invalidating the '772 patent (see schematic below).

At the Federal Circuit argument, the Judges asked "Isn't this Gilead?" Novartis pointed to footnote 5 of Gilead where the Court said the public's right to practice the expired patent may be further limited by some other means established by Congress, such as a patent term extension. Id. Novartis also circled back to the idea that this would not be an unjust extension, pointing to Congress' action as the reasons for the extension.

Breckenridge argued that this is Gilead. When questioned by the Court about the effect of a terminal disclaimer, Breckenridge argued that the terminal disclaimer is not tied to the term of the patent, but rather to the public's right to practice the claimed invention at expiration and that double patenting protects the public by preventing the monopoly from extending beyond the term of the first-expired patent. Tellingly, the Court also asked if an affirmance would be the first time that a pre-GATT patent got less than the 17-year term due to ODP. Breckenridge urged that this was not a request for a curtailed patent term but rather a request for invalidity.

Here, this is a very narrow situation. Precedent might be read improperly, to suggest that, based on the expiration dates, the monopoly over the claimed invention should end with the earlier expiration date. However, the Court should reason that the differences in the patent terms are a result of statute and upholding the district court's decision would cut short the patent term set forth in the pre-GATT law. Reading the tea leaves, the Federal Circuit will reverse the district court decision and create a judicial exemption to the judicially created doctrine of ODP when the expiration dates of possible double patenting references are different due only to their pre- and post-GATT status and when application of ODP would curtail the 17-year term of the pre-GATT patent.

Conclusion

Looking at arguments that have failed at the Federal Circuit, it is unlikely that lack of "gamesmanship" will prevent application of ODP, but differences in controlling statutes, as in Breckenridge, may preclude ODP. Nor, as in Ezra, will the court place the burden on the patent owner for making some kind of "correct" or "thoughtful" choice when seeking a patent term extension. Rather, the only limitation by statute is that only one patent may be extended.

Footnotes

1 The Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA) was enacted as part of a larger process called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The URAA changed the U.S. patent term to 20 years from the earliest effective non-provisional filing date. Before the URAA, the U.S. patent term was 17 years from filing. When the URAA was enacted, there was provision for a transition period when patent owners could choose the longer of 17 years from issuance or 20 years from filing. See Uruguay Round Agreement Act, Pub. L. No. 103–465, 108 Stat. 4809, 4983 (1994), amending 35 U.S.C. § 154.

2 Gilead, 753 F.3d at 1216. That policy, of course, has limits not before the Court in Gilead. First, any patents issuing from divisional applications filed in response to a restriction requirement are protected from a finding of ODP if consonance is maintained. 35 U.S.C. §121. Also, it has long been known in the U.S. patent system that a second-expiring patent that is patentably distinct from a first-expiring patent does not improperly extend the term of the first expiring patent. The classic example is where a second-expiring patent is directed to a species that is patentably distinct from a genus claim in the first-expiring patent. See, e.g., Brigham and Women's Hospital Inc. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 761 F.Supp.2d 210, 224 (D. Del. Jan. 7, 2011)("In the context of double patenting, an earlier patent claiming a large genus of pharmaceutical compounds does not preclude a later patent from claiming a species within that genus, so long as the species is novel, useful, and nonobvious. In re Kaplan, 789 F.2d 1574, 1577–80 (Fed.Cir.1986); see Eli Lilly & Co. v. Zenith Goldline Pharm., Inc., 364 F.Supp.2d 820, 909–10 (S.D.Ind. 2005). It is not surprising or controversial that either the same or a different inventor will improve upon and attempt to patent a novel, useful, and nonobvious variation of a compound claimed by an earlier patent. Kaplan, 789 F.2d at 1578. Generally, the genus or 'dominant' patent will expire while claims to the patentably distinct species or selection invention continue into the future. Id."). See also, UCB, Inc. v. Accord Healthcare, Inc., 890 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2018), where the claims to a later-expiring species were held patentably distinct from an earlier-expiring genus.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]