- within Criminal Law topic(s)

On August 6, 2024, the PTAB issued its first written decision applying a new test for obviousness of design patents. In Next Step Group, Inc. v. Deckers Outdoor Corp., IPR2024-00525, Paper 16 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 6, 2024) ("Decision"), the PTAB applied the test pronounced by the Federal Circuit in LKQ Corp. v. GM Glob. Tech. Operations LLC, 102 F.4th 1280 (Fed. Cir. 2024) ("LKQ"). This decision illustrates how the PTAB, courts, and administrative agencies are likely to interpret the Federal Circuit's latest guidance for design patents.

Petitioner Next Step Group, Inc. ("NSG") asserted ten unpatentability grounds against U.S. Design Patent No. D927,161 ("'161 patent"), including eight obviousness theories. Decision at 8-9. The PTAB found that the petition's obviousness theories were not likely to prevail, and so it declined to initiate inter partes review.

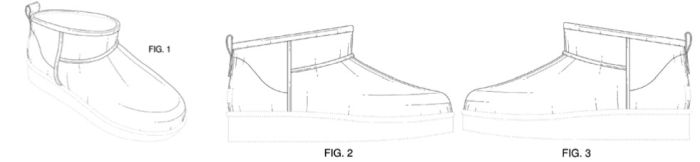

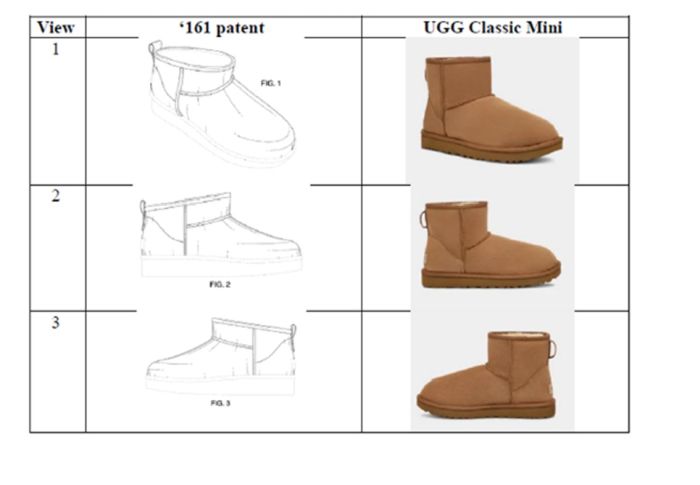

The '161 Patent covers a design for the upper portion of footwear, as shown below:

Decision at 4-5.

The PTAB first evaluated whether NSG's cited prior art references qualified as printed publications. [See previous post about this case, forthcoming]

The PTAB then turned to the merits, including Grounds 2 and 4-10, which were the first-ever design-patent obviousness grounds that the PTAB scrutinized under LKQ. In LKQ, the en banc Federal Circuit found the Rosen-Durling test "too rigid" in light of other Supreme Court precedent, and instead aligned design-patent obviousness with utility-patent obviousness under Graham v. John Deere and KSR v. Teleflex: "[T]he question of obviousness is resolved on the basis of underlying factual determinations, including: (1) the scope and content of the prior art; (2) any differences between the claimed subject matter and the prior art; (3) the level of skill in the art; and (4) when in evidence, objective evidence of obviousness or nonobviousness, i.e., secondary considerations." Decision at 33. [See our previous blog post on the topic here.]

In large part, the PTAB criticized NSG for not digging into the asserted prior art and the '161 patent and explaining why combining or modifying the prior art would have been obvious. The PTAB explained that one must "offer adequate reasoning why a designer would select, from all the possible design options," the specific elements of the claimed design, and address the differences between the claimed design and the prior art. Decision at 45.

The petition fared better when it came to the combination of "the Emu boot or CN'897, with the pull tab of the UGG Neumel Boot to make it easier to put on and remove the footwear from the foot." Decision at 45-46. NSG offered more support for that combination, claiming that "using the pull tab that matches the pull tab of the UGG Neumel boot was a simple design choice that involved no more than a mere substitution of one known element for another," and that "Patent Owner would have been motivated to include a pull tab consistent with its other long-used pull tabs." Decision at 46. Still, the PTAB was not swayed; while that may have addressed one feature, the petition failed to adequately address "the additional differences between the overall appearance" of the claimed design and asserted art. Id.

Light treatment of all the designs' differences plagued the rest of the petition. These differences are generally subtle: the PTAB evaluated the references' overall appearance, as well as features including "the ratio of the length of the foot opening to the length of the boot, the pull tab, and the sloping top line." Below is an example of some of those differences:

Decision at 47. The PTAB was meticulous in its analysis: features like a sloping top line versus straight, differences in pull tab shape and location, and even poor image quality led the PTAB to reject several grounds.

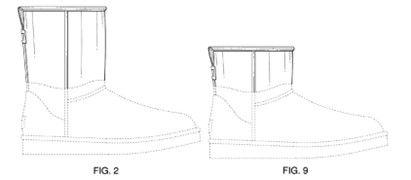

The PTAB disposed of the final three grounds based on boots with varied boot heights but essentially the same design, one of which is depicted in part below:

Decision at 52. The petition asserted that "to the extent the asserted primary references either alone or in combination . . . do not render the claimed design obvious because the UGG Classic Mini has a footwear upper with a slightly different length/width or shaft length, that it would have have been obvious to vary the length/width and shaft length" in view of these two prior art patents. Decision at 54. Again, the PTAB was unmoved. While these prior art references might teach varying shaft height, they didn't teach varying shaft width in the way the petition claimed.

Thus, none of NSG's asserted grounds for invalidity were persuasive, and the PTAB declined to institute inter partes review of the '161 patent. Nevertheless, the PTAB did shine some light on its application of the new LKQ test.

Takeaways:

Petitioners should be meticulous with their prior art references and arguments when challenging design patents, and ensure that their arguments address every aspect of a claimed design, with clear images taken from printed publications. Even slight variations in the shape of a line, or the ratio of height to width of a design, are important aspects. The new LKQ test is more wide-ranging and flexible, but petitioners must still carefully evaluate and explain every aspect of a claimed design, and any proposed modifications or combinations of the prior art that allegedly achieve it.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.