- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA), which always sat en banc and was the predecessor to today's Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), developed a rich body of jurisprudence relating to U.S. patent law. Titans of the U.S. patent bar, such as Judge Giles Sutherland Rich, who was a co-author of the 1952 Patent Act, populated the CCPA and rendered those decisions.

The CAFC adopted all CCPA holdings as binding precedent in its very first decision, South Corp. v. U.S., 690 F.2d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1982):

This appeal is the first to be heard, and this opinion the first to be published, by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, established October 1, 1982 by the Federal Courts Improvement Act of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-164, 96 Stat. 25.

The court sits in banc to consider what case law, if any, may appropriately serve as established precedent. We hold that the holdings of our predecessor courts, the United States Court of Claims and the United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA), announced by those courts before the close of business September 30, 1982, shall be binding as precedent in this court.

Id. at 1369 (emphasis added).

Overturning CCPA holdings should, therefore, require either a decision by an en banc Federal Circuit, as indicated in South Corp., or a decision by the CCPA overruling the precedent. The last chance the CCPA had to overrule one of its decisions was in 1982, some 40 years ago. And the Federal Circuit has rarely explicitly done so in the 40 years of its existence.1 One would thus conclude that nearly all CCPA authority remains as en banc precedent in the Federal Circuit.

But a recent Federal Circuit patent decision in Indivior UK Ltd. v. Reddy's Labs. S.A., 18 F.4th1323 (Fed. Cir. 2021), has caused a stir in the minds of some that the CCPA's influence over the Federal Circuit may be diminishing. We previously published on that case (here) and suggested that the Federal Circuit's decision may have conflicted with the CCPA's holdings from In re Wertheim, as argued by Judge Linn in his dissent from the majority opinion in Indivior.

Inspired by this seeming discrepancy between the decisions by the two courts in two factually similar cases, we looked at the patent cases decided by the Federal Circuit in 1983 (the first full year of the CAFC's existence), and those decided in 2021 (the most recent full year of CAFC decisions at the time of this article) to investigate whether the Federal Circuit is treating CCPA cases differently today compared to nearly 40 years ago.

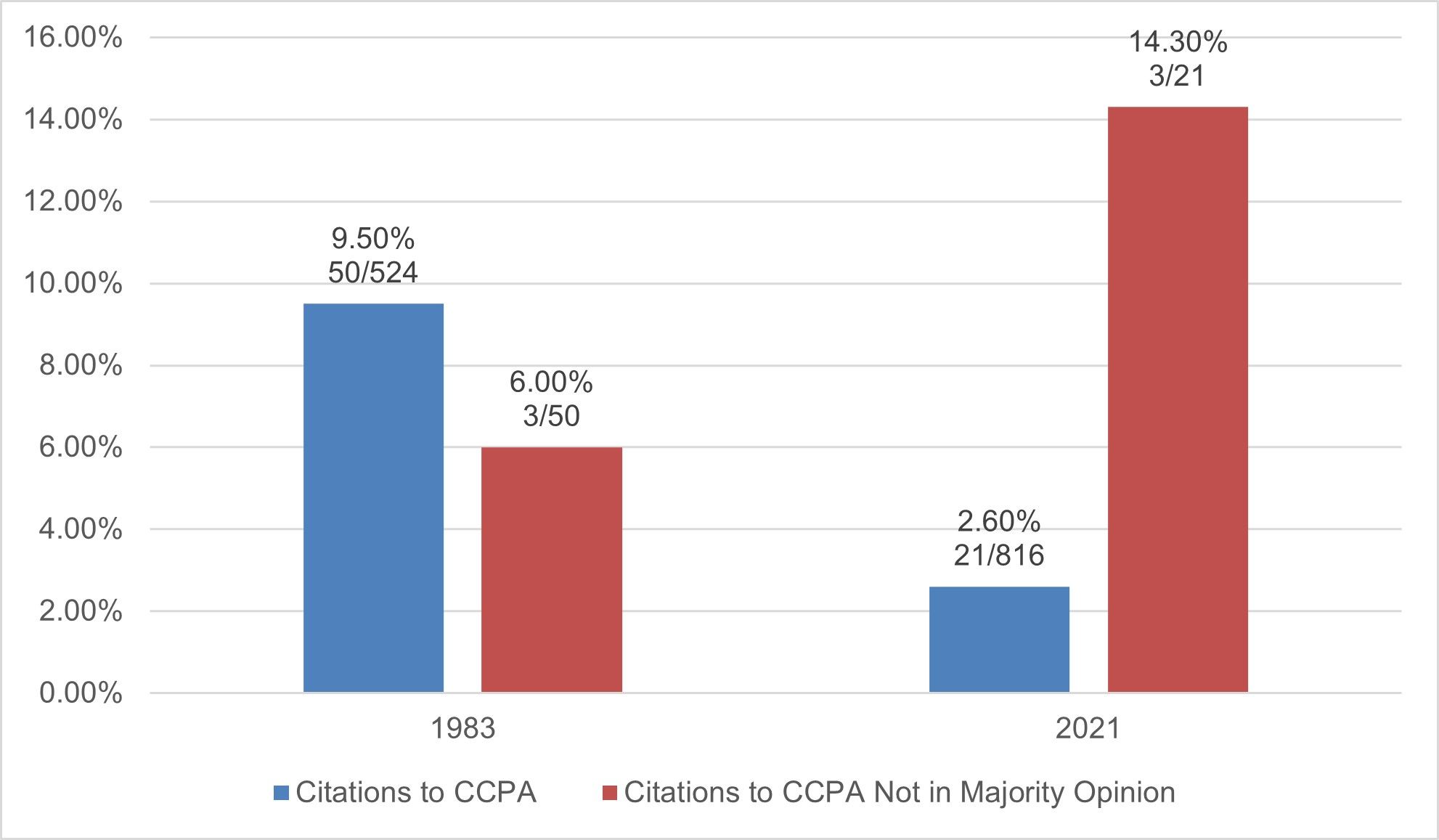

In 1983, fifty of the Federal Circuit's approximately 524 patent cases cited the CCPA (9.5%, 50/524).2 Forty-seven of the fifty decisions included a citation to the CCPA in the majority opinion to support a legal principle, while three of the fifty decisions (6%, 3/50) cited the CCPA only in the dissent or in summarizing a party's argument.

In 2021, twenty-one of the Federal Circuit's 816 patent cases included a citation to the CCPA (2.5%, 21/816).3 Eighteen of the twenty-one decisions included a citation to the CCPA in the majority opinion to support a legal principle, while three decisions (14%, 3/21) cited the CCPA only in the dissent or in summarizing a party's argument.

Fig. 1. CAFC Cases Citing CCPA Cases

Numerically, it appears that the CAFC relied on CCPA decisions less frequently in 2021 compared to 1983. In addition, a larger portion of those citations appeared only in the dissent or in summarizing a party's argument in 2021 compared to 1983. To the extent these statistics indicate that the import of CCPA decisions may be diminishing, we are humbly undertaking a multi-part series of posts to raise the patent bar's collective conscience regarding key CCPA cases relating to the patentability requirements of sections 101, 102, 103, and 112 of the patent statute, and to the judicially created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (ODP).

We believe that such an effort would benefit the patent bar because CCPA jurisprudence provides a treasure-trove of arguments for practitioners prosecuting and litigating patents in the face of assertions of unpatentability during ex parte prosecution and patent trials before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), as well as invalidity in district court and the International Trade Commission.

Hence, in succeeding parts of this series, we will analyze CCPA precedent by points of law, such as written description, enablement, indefiniteness, anticipation, obviousness, ODP, and subject matter eligibility. We are hopeful that our efforts will inspire the patent bar to apply these CCPA cases, which remain binding precedent some 40 years since the CCPA ceased its existence. In short, we believe that the reasoning of the CCPA should continue to be applied for decades, but that will only happen if the patent bar keeps the decisions top of mind.

Footnotes

1. See In re Donaldson Co., 16 F.3d 1189, 1193-94 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (en banc) ("To the extent that In re Lundberg, 44 C.C.P.A. 909, 244 F.2d 543, 113 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 530 (CCPA 1979), In re Arbeit, 41 C.C.P.A. 719, 206 F.2d 947, 99 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 123 (CCPA 1953), or any other precedent of this court suggests or holds to the contrary, it is expressly overruled."). See also, In re Tam, 808 F.3d 1321, FN1 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc) ("To be clear, we overrule In re McGinley, 660 F.2d 481 (C.C.P.A. 1981), and other precedent insofar as they could be argued to prevent a future panel from considering the constitutionality of other portions of § 2 in light of the present decision.").

2. Total number of CAFC patent decisions for 1983 were estimated from a LEXIS search, as Court statistics do not go back that far.

3. Total number of CAFC patent decisions for 2021 is based on US Court reports.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.