Allegations of indirect patent infringement require, among other things, pleading that the defendant had knowledge of the asserted patent. It is not well-settled law, however, whether notice of a complaint itself satisfies this knowledge requirement.

In the absence of U.S. Supreme Court and U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit precedent, district courts across the country have reached different holdings on this issue — some have held that a plaintiff must plead that the defendant had presuit knowledge of the asserted patents, while others have held that notice of the complaint satisfies the knowledge requirement.

In light of two recent, potentially overlooked cases,1 this article will explore the different approaches taken by district courts and analyze how they have ruled on this issue. In doing so, this article will provide guidance regarding allegations of indirect patent infringement and increasing the likelihood of surviving a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss.

Indirect Patent Infringement

Under U.S. patent law, a patentee may recover damages from an infringer for direct and indirect infringement.2

Direct infringement occurs when an infringer practices each and every element of a patent claim, either literally or through the doctrine of equivalents.3

Indirect infringement occurs when an infringer does not itself practice each and every element of a claim but rather actively induces or contributes to the infringement of a third party.4

Induced infringement requires: (1) knowledge of the infringed patent; and (2) intentionally aiding and abetting a third party to infringe.5

Contributory infringement requires: (1) knowledge of the infringed patent; (2) providing to a third party a material component of an infringing article; and (3) that the component is especially made or adapted for use in such infringing article.6

Hence, unlike for direct infringement, which is a strict liability tort,7 a patentee alleging indirect infringement must prove that the accused infringer had knowledge of the asserted patent.8

Pleading the Knowledge Requirement

Because indirect patent infringement requires that the accused infringer have knowledge of the asserted patent, a plaintiff bringing a claim for indirect infringement must plead such knowledge.9

In the absence of evidence that the accused infringer had knowledge, some plaintiffs attempt to rely on notice of the complaint to the defendant to satisfy the knowledge requirement, because the defendant would have had knowledge of the asserted patent at least as of such date.

In response to such pleadings, defendants often file a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim, arguing that the complaint did not and could not allege every element of the claim, because at the moment of filing the defendant did not have the requisite knowledge.10

Courts have reacted differently to this situation. Some courts accept the complaint as satisfying the knowledge requirement and allow the plaintiff to allege post-complaint damages.

For example, in the 2014 MyMedicalRecords Inc. v. Jardogs LLC decision, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California held that notice of the complaint alleging indirect infringement did satisfy the knowledge requirement, reasoning that holding otherwise would not be reasonable because the defendant did indeed have actual knowledge of the asserted patent through the complaint.

The court explained:

A defendant should not be able to escape liability for postfiling [indirect] infringement when the complaint manifestly places the defendant on notice that it allegedly infringes the patents-in-suit. Holding otherwise would give a defendant carte blanche to continue to indirectly infringe a patent — now with full knowledge of the patents-in-suit — so long as it was ignorant of the patents prior to being served itself with the complaint.11

Other courts, however, have disagreed with this reasoning. For example, in the March ZapFraud Inc. v. Barracuda Networks Inc. decision, the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware held that notice of a complaint alleging indirect infringement did not satisfy the knowledge requirement. The U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida recently held the same in D3D Technologies Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.

The ZapFraud court explained:

The purpose of a complaint is to obtain relief from an existing claim and not to create a claim. ZapFraud has identified, and I know of, no area of tort law other than patent infringement where courts have allowed a plaintiff to prove an element of a legal claim with evidence that the plaintiff filed the claim. The limited authority vested in our courts by the Constitution and the limited resources made available to our courts by Congress counsel against encouraging plaintiffs to create claims by filing claims. It seems to me neither wise nor consistent with principles of judicial economy to allow court dockets to serve as notice boards for future legal claims for indirect infringement and enhanced damages.12

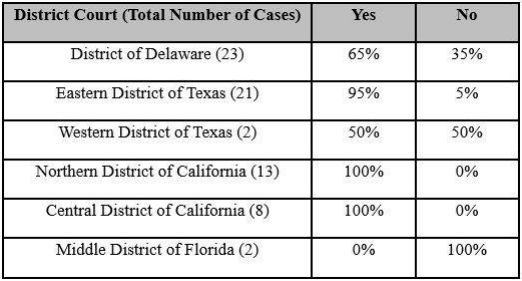

Table 1 below highlights the split among and, even within, certain district courts in the past six years regarding whether a plaintiff may rely on the complaint to satisfy the knowledge requirement for indirect infringement.13

Table 1: Can a Plaintiff Rely on the Complaint to Satisfy the Knowledge-of-thePatent Requirement for Indirect Infringement?

As Table 1 shows, some district courts, e.g., the U.S. District Courts for the Northern and Central Districts of California, have been more consistent in their holdings on this issue, while others, e.g., the District of Delaware, have been split.

Thus, patentees wishing to bring a claim of indirect infringement and satisfy the knowledge requirement through the complaint itself should consider bringing suit in an available district more favorable to this position. On the other hand, defendants in such a situation should consider the district's, and the particular judge's, holdings on this issue in determining whether to bring a Rule 12(b)(6) motion.

Alternative Courses of Action

Patentees wishing to bring a claim of indirect infringement in a jurisdiction that may not allow for pleading knowledge of the asserted patent based on the complaint, but lacking such evidence, have several alternative courses of action.

For example, the patentee could provide the alleged infringer with notice of the patent before filing the complaint.14 Though such a notice would likely satisfy the requisite knowledge of the patent for pleading indirect infringement,15 it has one substantial risk — the possibility of the alleged infringer's filing a declaratory judgment action,16 particularly in a jurisdiction or venue unfavorable to the patentee.

Federal law provides that a declaratory judgment action is only appropriate "[i]n a case of actual controversy."17 The Supreme Court held that this requirement is met when the totality of the circumstances shows "a substantial controversy, between parties having adverse legal interests, of sufficient immediacy and reality to warrant relief."18

Applying this standard, the Federal Circuit has held that an actual controversy may exist when the patentee asserts and shows a willingness to enforce its patent rights.19 For example, in the 2007 SanDisk Corp. v. STMicroelectronics Inc. decision, the Federal Circuit determined that a patentee clearly communicated its intent to enforce its rights where the patentee sought a right to royalty payments and provided detailed infringement analysis explaining its infringement theory, among other things.20

However, courts also look at other surrounding factors, including whether the patentee is a patent assertion entity,21 the litigation history of the parties,22 and interactions apart from the notice letter.23

Thus, if a patentee wishes to provide a potential infringer with notice of the patent but also wishes to avoid declaratory judgment jurisdiction, the patentee should take great care in wording such notice to not create an actual controversy. There is no clear distinction between providing sufficient knowledge of the patent and creating an actual controversy, and it is often a fact-intensive inquiry. 24

Hence, patentees wishing to provide such notice should carefully consider the totality of circumstances of the case as well as the intricacies of the current law regarding an actual controversy in jurisdictions in which the alleged infringer may potentially bring a declaratory judgment action.

However, a notice letter merely identifying the patentee's patent(s) and the other party's product(s) may be less likely deemed enough to confer declaratory judgment jurisdiction. 25 And though this approach has its risks, it may also provide some benefit, as it may potentially augment the time period for which damages can be recovered. 26

Ultimately, patentees wishing to provide notice of a patent to an alleged infringer, without creating an actual controversy, should carefully word such a notice to not show "intent to escalate the dispute." 27 Patentees should also consider the totality of the circumstances and the current state of the law regarding declaratory judgment jurisdiction in deciding how and whether to provide such notice.

To circumvent the risk of a potential declaratory judgment action, a patentee may file a complaint alleging direct infringement of the asserted patent, if viable, and then amend the complaint under Rule 15 to plead indirect infringement.

Under Rule 15, a plaintiff may amend its complaint prior to trial in two ways: (1) once as a matter of course within the earlier of 21 days of serving it, or 21 days after service of the defendant's answer or Rule 12(b), (e), or (f) motion; and (2) at any other time with the opposing party's written consent or the court's leave — to be freely given "when justice so requires." 28

Hence, patentees wishing to amend their complaint to add an allegation of indirect infringement based on post-suit knowledge of the asserted patent should be prepared to file an amended complaint within the time period provided for by Rule 15, so to not have to rely on the court's leave or the unlikely event of the opposing party's consent.

Though some courts have been amenable to this approach, 29 patentees should consider the most recent state of the law regarding this issue in the jurisdiction in which they wish to file their complaint.

However, a patentee may potentially wish to file its complaint in a district that does not allow the patentee to amend the complaint to plead indirect infringement based on knowledge from the first complaint. 30

In such a scenario, the patentee may allege direct infringement and then use discovery as a mechanism to seek facts related to the alleged infringer's knowledge of the asserted patent. Were such facts to be discovered, a court would likely grant the patentee leave to amend its complaint to plead indirect infringement.31

Thus, the patentee should specifically tailor its discovery strategies to at least seek information potentially related to the defendant's knowledge of the asserted patent, among the other requisite elements of indirect infringement.

Conclusion

In the absence of controlling precedent, district courts disagree on whether a complaint may itself provide knowledge of the asserted patent to satisfy the knowledge requirement for pleading indirect patent infringement. Thus, litigants in actions involving claims of indirect infringement should be aware of how the district court they are litigating in, and the particular judge, has held on this issue.

Additionally, patentees wishing to bring claims of indirect infringement should be cognizant of the available alternatives to satisfying the knowledge requirement, including the risks and requirements of those alternatives.

Footnotes

1. ZapFraud, Inc. v. Barracuda Networks, Inc. , No. 19-1687-CFC-CJB, 2021 WL 1134687 (D. Del. Mar. 24, 2021); D3D Tech., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp. , No. 6:20-cv-1699-PGB-DCI, 2021 WL 2194601 (M.D. Fla. Mar. 22, 2021).

2. See generally 35 U.S.C. § 271 (2010).

3. See Centillion Data Sys., LLC v. Qwest Commc'ns Int'l, Inc. , 631 F.3d 1279, 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2011); Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Motorola Mobility LLC , 870 F.3d 1320, 1328-29 (Fed. Cir. 2017); see also 35 U.S.C. § 271(a).

4. See 35 U.S.C. § 271(b)-(c).

5. 35 U.S.C. § 271(b); Warsaw Orthopedic, Inc. v. NuVasive, Inc. , 824 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2016) ("[I]nduced infringement requires not 'only knowledge of the patent' but also 'proof the defendant knew the [induced] acts were infringing.'" (alteration in original)); DSU Med. Corp. v. JMS Co. , 471 F.3d 1293, 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ("To establish liability under section 271(b), a patent holder must prove that once the defendants knew of the patent, they 'actively and knowingly aid[ed] and abett[ed] another's direct infringement.'" (alteration in original)).

6. 35 U.S.C. § 271(c); Nalco Co. v. Chem-Mod, LLC , 883 F.3d 1337, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2018) ("[C]ontributory infringement requires knowledge of the patent in suit and knowledge of patent infringement." (quoting Commil USA, LLC v. Cisco Sys., Inc. , 135 S. Ct. 1920, 1926 (2015)).

7. See BMC Res., Inc. v. Paymentech, L.P. , 498 F.3d 1373, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (overruled on other grounds); D3D Tech., 2021 WL 2194601.

8. Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A. , 131 S. Ct. 2060, 2062-63, 2068-69 (2011). Similar to indirect infringement, allegations of willful infringement also require knowledge of the patent. See 35 U.S. Code § 284 (2011); Bayer Healthcare LLC v. Baxalta Inc. , 989 F.3d 964 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

9. See, e.g., Lifetime Indus., Inc. v. Trim-Lok, Inc. , 869 F.3d 1372, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2017) ("For an allegation of induced infringement to survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint must plead facts plausibly showing that the accused infringer 'specifically intended [another party] to infringe [the patent] and knew that the [other party]'s acts constituted infringement.'" (alteration in original)).

10. See, e.g., ZapFraud, 2021 WL 1134687; D3D, 2021 WL 2194601; Script Security Solutions L.L.C. v. Amazon.com, Inc. , 170 F.Supp.3d 928 (E.D. Tex. 2016); Simplivity Corp. v. Springpath, Inc. , No. 4:15-13345-TSH, 2016 WL 5388951 (D. Mass. 2016); Regents of Univ. of Minnesota v. AT & T Mobility LLC , 135 F.Supp.3d 1000 (D. Minn. 2015).

11. MyMedicalRecords, Inc. v. Jardogs, LLC , 1 F.Supp.3d 1020, 1025 (C.D. Cal. 2014).

12. ZapFraud, 2021 WL 1134687, at *4 (internal quotations and citations omitted).

13. Only post-2015 decisions considered.

14. This is solely with regard to satisfying the requirement of the alleged infringer's knowledge of the patent, and not other elements required for indirect infringement (e.g., intent to induce for induced infringement, and providing to a third party a material component of an infringing article for contributory infringement).

15. See, e.g., Ocean Innovations, Inc. v. Archer , 483 F. Supp. 2d 570, 583 (N.D. Ohio 2007) (finding that plaintiff's two notice letters to defendant stating plaintiff's belief that defendant infringed the asserted patent provided sufficient knowledge); Intellicheck Mobilisa, Inc. v. Honeywell Int'l Inc. , No. C16-0341JLR, 2017 WL 5634131, at *4 n.4 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 21, 2017) ("A notice letter generally informs the putative infringing party of potential infringement."); but see Cascade Comput. Innovation, LLC v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd. , 77 F. Supp. 3d 756, 766 (N.D. Ill. 2015) (finding that a notice letter merely listing the asserted patent in an appendix and not directly referencing it did not suffice).

16. See 28 U.S.C. § 2201(a) (2020).

17. Id.

18. MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. , 549 U.S. 118, 127 (2007).

19. SanDisk Corp. v. STMicroelectronics, Inc. , 480 F.3d 1372, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ("We hold only that where a patentee asserts rights under a patent based on certain identified ongoing or planned activity of another party, and where that party contends that it has the right to engage in the accused activity without license, an Article III case or controversy will arise and the party need not risk a suit for infringement by engaging in the identified activity before seeking a declaration of its legal rights.").

20. Id. at 1382.

21. Hewlett–Packard Co. v. Acceleron LLC , 587 F.3d 1358, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

22. Prasco, LLC v. Medicis Pharm. Corp. , 537 F.3d 1329, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

23. Innovative Therapies, Inc. v. Kinetic Concepts, Inc. , 599 F.3d 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

24. See, e.g., Edmunds Holding Co. v. Autobytel Inc. , 598 F. Supp. 2d 606 (D. Del. 2009); Microsoft Corp. v. Phoenix Sols., Inc. , 741 F. Supp. 2d 1156 (C.D. Cal. 2010); Element Six U.S. Corp. v. Novatek Inc. , No. CV 14-0071, 2014 WL 12586395 (S.D. Tex. June 9, 2014).

25. See, e.g., Hewlett–Packard, 587 F.3d at 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2009) ("[A] communication from a patent owner to another party, merely identifying its patent and the other party's product line, without more, cannot establish adverse legal interests between the parties, let alone the existence of a 'definite and concrete' dispute. More is required to establish declaratory judgment jurisdiction."); SanDisk, 480 F.3d at 1381 ("[D]eclaratory judgment jurisdiction generally will not arise merely on the basis that a party learns of the existence of a patent owned by another or even perceives such a patent to pose a risk of infringement, without some affirmative act by the patentee."); Element Six, 2014 WL 12586395 (S.D. Tex. June 9, 2014) (holding that patentee's communications asking other party for information and providing for the possibility of patent infringement was not sufficient to create an actual controversy).

26. 35 U.S.C. § 287(a) (2011) (limiting damages in the absence of marking "except on proof that the infringer was notified of the infringement").

27. 3M Co. v. Avery Dennison Corp. , 673 F.3d 1372, 1379-80 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

28. Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a)(1)-(2).

29. See, e.g., Helios Streaming, LLC v. Vudu, Inc. , No. 19-1792-CFC-SRF, 2020 WL 2332045, at *5 (D. Del. May 11, 2020); Zond, Inc. v. SK Hynix Inc. , Nos. 13–11591–RGS, 13–11570–RGS, 2014 WL 346008, at *3 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 31, 2014); Intellicheck Mobilisa, Inc. v. Honeywell Int'l Inc. , 2017 WL 5634131, at *11-12; but see Orlando Commc'n LLC v. LG Elecs., Inc. , No. 6:14–cv–1017–Orl–22KRS, 2015 WL 1246500, at *9 (M.D. Fla. Mar. 16, 2015) ("'Prior to suit' does not mean prior to the current iteration of the Complaint. If, as Plaintiff suggests, failure to allege pre-suit knowledge could be cured merely by filing another complaint (without alleging new facts), then the knowledge requirement would be superfluous."); Polaris PowerLED Tech., LLC v. Vizio, Inc. , No. SACV 18-1571 JVS (DFMx), 2019 WL 3220016, at *4-5 (C.D. Cal. May 7, 2019) (denying plaintiff leave to amend to replead its claims for induced infringement).

30. See, e.g., Orlando Commc'n LLC v. LG Elecs., Inc. , No. 6:14–cv–1017–Orl–22KRS, 2015 WL 1246500 (M.D. Fla. Mar. 16, 2015).

31. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a)(2) ("The court should freely give leave [to amend the complaint] when justice so requires."); Wizards of the Coast LLC v. Cryptozoic Entm't , 309 F.R.D. 645 (W.D. Wash. 2015) (granting plaintiff leave to amend its complaint to include allegations of indirect infringement after relevant facts were unearthed during discovery); Westell Techs., Inc. v. Hyperedge Corp. , No. 02 C 3496, 2003 WL 22088039, at *3 (N.D. Ill. Sept 8, 2003) (allowing patentee leave to amend its complaint to include allegations of contributory infringement because plaintiff "understood that a contributory infringement count was appropriate only after it received HyperEdge's interrogatory responses.").

Originally Published by Law360.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.