- within International Law topic(s)

- within International Law, Technology and Strategy topic(s)

Michael R. Smiszek*

The General Interpretive Rules (GIRs) are the legal backbone of the Harmonized System. In the intervening years since the Harmonized System was first unveiled in 1983, a substantial and ever-growing body of articles, commentaries, administrative binding rulings, and, most important, judicial opinions has been published about the scope and application of the GIRs – and yet a conspicuous gap exists in the literature with regard to one particular rule: GIR 4. This article attempts to fill that gap by exploring the intent, circumstances, barriers, and practices that govern the legal application of this rarely used rule. Constrained by the scarcity of insightful authoritative guidance on GIR 4, this article necessarily is premised upon a plain-meaning construction of the rule and to a significant extent on inference drawn from the author's practical experience with the Harmonized System.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Harmonized System (HS) is the classification nomenclature used to facilitate customs clearance for nearly all crossborder trade.1 The World Customs Organization (WCO) released the initial version of the HS in 1983 after more than a decade of study, negotiation, and drafting, and in 1988 member nations began to implement it as the framework for their national tariff nomenclatures.2 The WCO reported in 2018 that 'more than 200 economies and Customs or Economic Unions' enjoy the efficiency, uniformity, and consistency provided by the HS.3 By any measure the HS has become, after more than three decades of service, a ubiquitous and indispensable element of global trade.

An importer's relationship with the HS may be framed as either a blessing or a curse. Although at first glance a new importer may see the HS as a dauntingly massive document, its size and complexity is mitigated by a rigid hierarchical structure governed by legally binding General Interpretive Rules (GIRs).4 Successful importers understand that this rigid structure and rules-based governance are a blessing that establishes, for all parties touching a cross-border transaction, a common basis for understanding customs-related risks and costs with greater clarity, certainty, and consistency. And yet the HS is a curse to those importers that fail to invest in trade compliance practitioners (whether directly or as agents) who have the requisite HS classification expertise demanded by customs agencies. Failure to understand the fundamental rules of the HS may cause an importer to misclassify its products and thus pay more in customs duties and import-related taxes than is legally required. But worse, HS incompetence or ignorance may lead to civil or criminal penalties5 when misclassification causes a duty underpayment or avoidance of a regulatory requirement.6 And we ought not to overlook the non-regulatory costs of an inadequate HS process, as the misclassification of inputs and finished goods may lead to confusion among employees, customer dissatisfaction (for instance, when a shipment is delayed or detained, or when a free trade agreement certificate is incorrect), or may increase the risk of ill-informed strategic business decisions (such as component sourcing or factory relocation analyses).

2 THE GENERAL INTERPRETIVE RULES

The six GIRs are the legal principles that must be satisfied for every classification decision.7 The GIRs establish the boundaries of inquiry and then drive the analysis forward, following a structured methodology that begins with a factual determination and ends with a legal conclusion within those boundaries. In many instances these rules guide a practitioner in a fairly mechanical manner to an objective and uncontroversial decision that requires minimal analytical effort – for example, fresh cauliflower (heading 0704), steel springs (7320), and fishing rods (9507) are straightforwardly classified under GIR 1 and, at the subheading level,8 under GIR 6. Yet in many other instances the GIRs require a practitioner to make a subjective decision based on qualitative characteristics susceptible to reasonable but divergent interpretation under vague and ambiguous legal standards such as specificity, essential character, and kinship. When the GIRs demand examination under a subjective lens, it is, in fact, not unusual for two experienced practitioners, each using an appropriate blend of heuristic problem-solving, intuition, and methodical diligence, to reach different but legally defendable conclusions about how a product ought to be classified. Among the many classes of goods vulnerable to subjective analysis are mixtures and combinations comprising different materials or components, multifunctional products, newly conceived products, kits and retail sets, and the often nettlesome 'parts and accessories'. But regardless of the challenges presented by a classification analysis, the decision always must be reached within the confines of the GIRs.

GIR 1 is the fundamental rule for effectively navigating the HS. The influence of GIR 1 is omnipresent; just as each new day begins with a sunrise, each classification decision necessarily begins with GIR 1. Although a decision never relies on all six GIRs, every heading-level analysis invokes at least GIR 1, and every analysis conducted at a subheading level invokes at least GIR 1 and GIR 6. GIRs 1–4 are generally applied in sequential order, but only to the extent required by the nature or use of the product being classified. An analogy may help us understand the strict limits placed on the GIRs' applicability: we can think of GIRs 2 through 6 as five separate locked rooms in a house. (It is, of course, unnecessary to sequester GIR 1 in a locked room.) Entry into each locked room is allowed on a strict need-to-know basis in order to prevent inadvertent reliance on inapplicable GIRs. A fishing rod, for example, is classified prima facie under heading 9507 per the sole authority of GIR 1. Thus the rooms containing the other five GIRs remain locked because those rules can have no influence whatsoever on the decision. If the fishing rod is in an incomplete form that nonetheless embodies the essential character of a fishing rod, then the room holding GIR 2 is unlocked because the fishing rod is classified under 9507 by the authority of GIR 1 and GIR 2 (specifically GIR 2(a), which allows an incomplete item to be classified as if it were a complete item). At the subheading level, this incomplete fishing rod is classified under 9507.10 by application of GIR 1, GIR 2(a), and GIR 6, while the other GIRs necessarily remain inaccessible behind locked doors. The point of this locked-room analogy is to emphasize the unwritten but critical tenet that a GIR must be ignored, as if it did not exist, unless it is formally invoked as a consequence of a factual analysis. We see in section 3 infra how this self-activating nature of the GIRs is relevant to GIR 4.

The WCO intended that most heading-level decisions would be made under the exclusive authority of GIR 1, although GIR 2 and GIR 3 are also invoked with regularity. GIR 5 is invoked with far less frequency due to its limited scope with regard to special-purpose containers and packing materials. On the other hand, GIR 6 trails only GIR 1 in frequency of use due to its automatic applicability to any decision made at a subheading level.9 It is perhaps instructive to think of GIR 2, GIR 5, and GIR 6 as 'helping' rule applied in addition to the guidance provided by a 'primary' GIR, namely GIR 1, GIR 3, and the subject of this article, GIR 4.10 GIR 4 inarguably is the GIR invoked with far less frequency than any other GIR – we may therefore correctly infer that GIR 4 is, by design, the victim of the expansive reach of GIR 1 and GIR 3.

3 GENERAL INTERPRETIVE RULE 4

3.1 GIR 4 Revealed

GIR 4 is the shortest GIR:

Goods which cannot be classified in accordance with the above rules shall be classified under the heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin.

Our intent in this article is to conduct a behind-the-curtain analysis of GIR 4. But because none of the GIRs can be effectively understood in isolation, we must examine GIR 4 within the full context of the GIRs.11 Hence we begin our review by determining the GIR-based limitations on the legal applicability of GIR 4 relative to the other GIRs. We find that GIR 4 cannot be invoked under the following circumstances:

- When a heading is determined, prima facie, solely under GIR 1;

- When GIR 2(a) or (b) are invoked in support of a GIR 1 decision;

- When application of GIR 1, whether or not aided by GIR 2(a) or (b), identifies, prima facie, two or more headings, thus sending the decision into GIR 3; or

- When GIR 2(b) sends the decision into GIR 3.

Notwithstanding the limitations in (2), (3), and (4), GIR 4 is compatible with GIR 2. Thus an incomplete, unfinished, unassembled, or disassembled item is classifiable under GIR 4. And neither GIR 5 nor GIR 6 imposes limits on GIR 4, nor does any section or chapter note affect the application of GIR 4.

As stated previously, only in an exceptional fact set will a decision rely upon GIR 4. It is essentially a failsafe rule, a think-outside-the-box option of last resort intended to ensure that an HS provision can be found for even the most unusual or contrived product.12 GIR 4 imposes no explicit legal limits on the scope of products to which it may be applied, but because GIRs 1, 2, and 3 resolve nearly all decisions before GIR 4 becomes eligible for consideration, the practical scope of GIR 4 is limited to uncommon manufactured or otherwise-worked products – products based, perhaps, on a novel design, formulation, or functional innovation – rather than, say, familiar natural products or common manufactured goods for which reasonably appropriate HS provisions are determinable under GIR 1, 2, or 3.13

But before we examine in greater detail the process that ultimately invokes GIR 4, we must understand the operative word in this rule: akin.

3.2 What Is Kinship?

Kinship is the sole evaluative criterion allowed under GIR 4.14 This exclusive reliance on kinship renders GIR 4 the most subjective GIR – indeed, it is the only GIR wholly premised on subjectivity, as GIR 4 provides no clinical criteria to facilitate an objective analysis, unlike GIRs 1–3. Whereas a decision under GIRs 1–3 may be reached either objectively or subjectively, depending on the product- or transaction-specific facts, a decision reached under GIR 4 is always a subjective exercise because of the vague nature of kinship.

But what is kinship? The HS itself offers no insight. Judicial and administrative guidance is nil (as we see in sections 4 and 5 infra). We find that the WCO's Explanatory Notes (ENs), which provide authoritative but non-binding commentary on the scope and interpretation of the HS, offer scant insight into the meaning of kinship within the context of GIR 4, noting merely that '[k]inship can, of course, depend on many factors, such as description, character, [and] purpose'. 15 In the absence of any direct clarity, we can turn to external authoritative sources to discern a word's common meaning; we find that the New Oxford American Dictionary (NOAD) defines akin as 'of similar character' 16 and kinship as 'a sharing of characteristics or origins'. 17

3.3 The Path to GIR 4

We noted earlier that the WCO designed the GIRs so that a decision to use GIR 4 could not be easily made. Indeed, the path to GIR 4 is meant to be inhospitable to all products except those that are most stubbornly resistant to conclusive analysis under GIR 1, 2, or 3. But every once in a while we face a classification conundrum that legitimately sends us down this rarely travelled path to GIR 4.

3.3.1 General Considerations

We may find, after consideration of GIR 1 and GIR 2 (and perhaps AUSRI 118), that we are unable to identify any heading that merits prima facie consideration for the particular product we are trying to classify. Hence the product is a de facto candidate for resolution under GIR 4. But GIR 4 is invoked with extreme infrequence for a reason; the fact that we entertain the possibility of using GIR 4 ought to be seen as a red flag that suggests our analysis is perhaps flawed in some subjective or objective aspect, so it is prudent to retrace our steps. Our initial analysis may be defective because we overlooked, misapplied, or misunderstood a crucial section or chapter note. Maybe further research will reveal a relevant binding ruling or court decision. Maybe we overlooked an applicable basket provision (more on basket provisions in section 3.4.2 infra). Or perhaps we mistakenly limited our search to finding an appropriate eo nomine provision, so we may instead try to find a use provision that fits, or vice versa. We may find that the product has a principal function that we failed to recognize, or maybe we did not consider alternative descriptions or names. Or, maybe we were simply lazy and committed the capital crime of relying on the alphabetic index in violation of GIR 1. A different perspective also may be helpful, so we may ask a colleague for his or her opinion. Chances are good that our reanalysis will reveal a path to classifying the product without reliance on GIR 4. And yet, even after our additional diligence, we may still conclude that GIR 4 is applicable.

Under GIR 4 we remain bound by the foundational principles laid down in GIR 1 and GIR 2. For instance, the primacy of the headings and legal notes, per GIR 1, is not diminished under a GIR 4 analysis. Moreover, a GIR 4 review must still consider the applicable country-specific interpretive rules that hold legal stature equal to the GIRs.

We can have confidence in our decision to invoke GIR 4 only when a heading truly cannot be determined, prima facie, under GIR 1 (and perhaps GIR 2). Under such circumstances our decision to invoke GIR 4 is justified. While it is self-evident that a decision reached under GIR 1 eliminates any opportunity to apply GIR 4, the mutually exclusive relationship (in truth, a non-relationship) between GIR 3 and GIR 4 requires deeper examination.

3.3.2 The Mutual Exclusivity of GIR 3 and GIR 4

GIR 3, by its plain language, must be invoked when, because of GIR 2(b) 'or for any other reason, goods are, prima facie, classifiable under two or more headings'. The last sentence of GIR 2(b) – i.e. '[t]he classification of goods consisting of more than one material or substance shall be according to the principles of rule 3' – sends the analysis into GIR 3, which irrevocably eliminates any opportunity to use GIR 4. Our understanding of the phrases for any other reason and prima facie in the context of GIR 3 is crucial. 'Prima facie' is not defined in the HS or the ENs, but the NOAD defines it as 'based on first impression' 19 – as applied to the GIRs it refers to a heading identified as a viable option by application of GIR 1 and, when needed, GIR 2.20 Therefore the moment two or more headings are identified, prima facie, as a consequence of GIR 1 (and GIR 2), we must invoke GIR 3, an act that automatically prohibits any consideration of GIR 4. Of the six GIRs, prima facie determination of a heading can occur only under GIR 1 (and, again, maybe GIR 2). The phrase 'for any other reason' may seem to imply infinite inclusivity but in fact the syntax of GIR 3 explicitly limits the phrase's influence to scenarios in which two or more prima facie headings are identified – in other words, because the prima facie determination of a heading is not possible under GIR 4, we cannot construe 'for any other reason' as an invitation to perform a GIR 4 analysis.21 Similarly the principles of specificity in GIR 3(a) and essential character in GIR 3(b) are inoperable unless GIR 3 is formally invoked (as illustrated by our locked-room analogy in section 2 supra), therefore these principles cannot be applied to a decision made under GIR 4 (unless a legal note demands otherwise22). In summary, when an analysis conducted under GIR 1 and GIR 2 finds, prima facie, two or more headings that describe a product (whether wholly or partially, or in an incomplete, unfinished or disassembled form), then the most appropriate heading must without exception be determined under GIR 3 rather than GIR 4.

Consider further that, were we to find ourselves in GIR 3 with two or more potential provisions to evaluate, we are prohibited from invoking GIR 4 because any stalemate in GIR 3 is resolved with finality by GIR 3(c). GIR 3 and GIR 4 are mutually exclusive and independent rules, hence it is legally impossible to engage both GIR 3 and GIR 4 in the same analysis at the same heading or subheading level. When our analysis lawfully takes us into GIR 3, we are forbidden from exiting GIR 3 with the intent of proceeding to GIR 4. And when our analysis takes us into GIR 4, we cannot have gotten there as a consequence of invoking GIR 3. Stated differently, GIR 3 and GIR 4 are terminal rules.

3.4 The Logic of GIR 4

A GIR 4 kinship analysis is a search for similarities. This self-evident fact is stated in the EN for this rule: 'In classifying in accordance with Rule 4, it is necessary to compare the presented goods with similar goods in order to determine the goods to which the presented goods are most akin'. 23 Conspicuously missing from this EN is the word 'heading' – this unique feature of the methodology under GIR 4 dictates that an analysis begins with the search for similar real-world articles or substances, not a search for similar HS headings. Also notable is that GIR 4's reliance on kinship neither presumes nor establishes a legal preference for, or distinction between, eo nomine or use provisions (whether principal use or actual use).

3.4.1 The GIR 4 Process

We can infer from the plain language of GIR 4 and the EN supra that a classification analysis is a three-step process, where the first two steps require factual determinations and the last step entails a legal decision:

- The first step starts with a search for products – not HS headings – that are similar, whether by name, function, use, or other relevant characteristics, to the product being classified.24 GIR 4 does not stipulate any standard for divining similarity, so the similarity may be tenuous or it may be substantial. This search may identify a single similar product, or it may reveal several similar products that exhibit varying characteristics or degrees of similarity.25 This is clearly a highly subjective effort where similarity is in the eye of a reasonable beholder. The key requirement of this step is that the search occurs entirely without regard to the HS.

- The second step requires that we compare the similar products identified in the first step in order to choose the one product that is most similar to the actual product. This is an easy determination when only one similar product is identified in step (1), in which case we can proceed directly to step (3). But when multiple similar products are under consideration then the relevant comparison of similarities continues, as in the first step, to be between the actual product and each similar product we have identified. This is in contrast to the process under GIR 3, where a GIR 3(a) specificity analysis or a GIR 3(b) essential character analysis effectively requires direct comparison of the terms of competing headings. But as with the first step, a GIR 4 comparison is extrinsic to the HS; rather than conduct a heading-to-heading legal comparison as we are obliged to undertake per GIR 3, we conduct a product-to-product factual comparison under GIR 4. As no formal criteria or guidance exists for evaluating and comparing kinship-conferring characteristics, a determination of kinship is an inherently subjective exercise conducted outside of the HS.

- We move on to the third step after we have factually determined, with reasonable and appropriate diligence, the similar product that is most akin to the actual product. Only now do we consult the pages of the HS. This final step requires review of the HS nomenclature to determine the legally applicable heading for that similar product – and this is the heading we will assign by kinship to our actual product (presuming, of course, the absence of any fatal conflict with the heading's language or the legal notes). The heading for the similar product is determined by applying the standard methodology prescribed by GIR 1, GIR 2, and, indeed, GIR 3, as legally appropriate – but GIR 4 cannot be used.

Were we to look, for the sake of argument, beyond a textual plain-meaning reading of GIR 4 we would see another practical consideration that further militates against heading-to-heading comparisons under this rule. Given the presumed peculiarity of any product that warrants examination under GIR 4, the headings we may be inclined to consider might be so dissimilar as to be incommensurable, in contrast to the greater relative similarity that typically exists between or among the headings considered, say, under a GIR 3(a) specificity analysis (and we will see an example of extreme dissimilarity in the chum ruling in section 4.1 infra). Hence the familiar heading-to-heading methodologies applied to a most specific comparison under GIR 3(a) or an essential character comparison under GIR 3(b) do not equate to a product-to-product most akin determination under GIR 4.

3.4.2 GIR 4 and Its Relationship with Basket Provisions

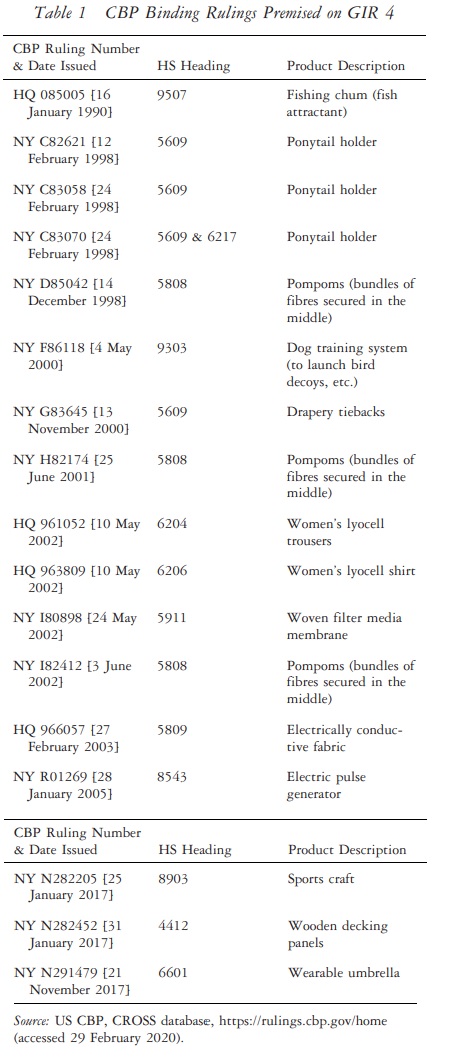

The HS would be an ineffective tariff nomenclature were it not for basket provisions.26 These residual, or 'catch-all', categories are so integral and necessary to HS classification methodology that national courts have had occasion to issue many opinions over the years that have addressed the reach and function of basket provisions.27 Thus an informed appreciation of GIR 4's limitations requires a closer look at its relationship with basket provisions. All HS chapters include basket provisions for non-enumerated goods that are not classifiable under a more specific heading, and these provisions typically are prefaced with 'other' or qualified by language such as 'not elsewhere specified or included'. 28 Under most headings we find basket subheadings, and many subheadings are further subdivided, perhaps several times over, into ever more specific sub-subheadings, which inevitably include basket provisions. These basket provisions – whether at a heading or subheading level, and whether they are eo nomine or use provisions – are implicitly designed to facilitate decisions under GIRs 1–3 rather than GIR 4.29 Heading 8214, for example, is a compound heading that includes 'Other articles of cutlery', the scope of which effectively precludes the use of GIR 4 for pretty much any hand-held implement that has a cutting blade. Although heading 8214 is a partial basket provision (only the clause before the first semicolon is a basket provision), a number of headings exist exclusively as basket headings. Three of the most commonly used chapters for manufactured goods are Chapters 84, 85, and 90, which are the primary chapters for mechanical and electrical machines and devices. Each of these chapters include broad basket headings that make it virtually impossible to invoke GIR 4 because GIRs 1–3 step in to assert jurisdiction over the classification of the class or kind of goods generally captured by these chapters. Three of these basket headings are:

The material-based basket heading is another type of residual provision that significantly reduces the employment opportunities for GIR 4. For example, a plastic item that does not appear to have a home under a more specific heading is classified, absent a contrary reason, under basket heading 3926 ('Other articles of plastic'), per GIR 1. Similarly a composite good that comprises, say, a combination of plastic, wood, and copper components might ultimately be classified, per GIRs 2(b) and 3, by choosing the most appropriate basket heading from among headings 3926, 4421, or 7419. Other-articles-of material-based basket provisions such as these exist throughout the HS for items made wholly or partly from many common substances and materials (e.g. heading 6914 for ceramics, 7020 for glass, 7326 for iron and steel, or 8007 for tin), a reality that necessarily limits the applicability of GIR 4.

When a product is classifiable, prima facie, under a basket provision based upon GIRs 1 and 2, or as a consequence of GIR 3, then we are prohibited from using GIR 4 to classify the product under a different provision. Stated differently, when a decision can be made within the confines of GIRs 1, 2, and 3, then we know incontrovertibly that GIR 4, by definition, can never be invoked. Put differently still, establishing kinship between a product and the goods described in a provision – to whatever degree and by whatever characteristics we deem reasonable, and whether or not a basket provision is implicated – does not grant us the authority to disregard another provision that is legitimately identified under the binding authority of GIRs 1, 2, or 3. Therefore we must never think in terms of kinship except when actually conducting an analysis pursuant to GIR 4.30

3.4.3 GIR 4 at a Subheading Level

When a heading is determined per GIR 4, the analysis must, as under any GIR, begin anew at the first subheading level and then again at each inferior subheading level until the final answer is reached, guided by GIR 6. As a practical matter GIR 4 is invoked only once, at the beginning when searching for a similar product and its corresponding heading, although GIR 6 makes it is legally possible (albeit highly improbable) to use GIR 4 for a subheading decision. By already deciding upon a heading, whether under GIRs 1–3 or by conducting a similar product analysis under GIR 4, the practical need to conduct a GIR 4 kinship determination within the limited scope of the subheadings is virtually nil. Thus GIRs 1 and 6 are typically sufficient to guide us at the subheading level. With specific regard to a similar product that is legitimately identified, per GIR 4, as a 'part' or 'accessory' under a heading that includes 'parts' or 'parts and accessories', such part or accessory is generally classified at a subheading level pursuant to the standard methodology required by GIR 1 and GIR 6 (and applicable national rules).

4 GIR 4 AND US BINDING RULINGS

We identify in this section the binding classification rulings published by US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) since 1988 that explicitly cite GIR 4 as justification for CBP's decisions. For purposes of this article we conducted a review of several of these rulings to validate whether the products were analysed appropriately under GIR 4, and in section 4.1 infra we present our findings. And then in section 4.2 infra we review two rulings in the context of GIR 4 even though CBP did not implicate the kinship rule.

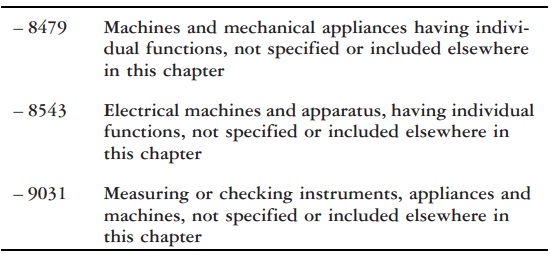

4.1 US Binding Rulings Premised on GIR 4

We now look at a few of the binding rulings issued by CBP that are formally predicated on GIR 4. An objective indicator of how few products are actually eligible for review under GIR 4 is the fact that CBP's CROSS database31 includes more than 200,000 rulings, yet in Table 1 we see that fewer than twenty of these are classification rulings premised on GIR 4, and of these twenty rulings, several are duplicative (e.g. three rulings each for ponytail holders and pompoms):

We begin with HQ 085005, a 1990 ruling in which CBP applied GIR 4 to classify an Australian 'chum' product used by fishermen to attract fish. This ruling looked at several disparate headings as potential prima facie provisions per GIR 1, including 0511, 2301, and 9507. While CBP dismissed these headings under an objective GIR 1 analysis, ultimately CBP chose 9507 by virtue of the greater latitude afforded under a subjective GIR 4 kinship analysis. CBP said that 'heading 9507 ... provides for fishing rods, fish hooks and other line fishing tackle ... parts and accessories thereof. The subject chum is most akin to the merchandise described under heading 9507 [and], by application of [GIR] 4, is properly classifiable under this heading.' CBP made this determination despite admitting that the plain language of 9507 limited its scope to artificial lures and bait, noting that 'it can be argued by inference that the Harmonized Committee intended to exclude natural and organic bait from the scope of this heading.' Presuming for a moment that it was proper to seek resolution under GIR 4, this ruling illustrates how the kinship standard under GIR 4 does not require absolute fidelity between the actual product and the terms of a heading, unlike the requirements of GIRs 1–3. So whereas GIR 4 requires that the similar product must conform to the terms of a heading, such conformance of the actual product is not required. CBP also considered whether the correct heading could be determined under GIR 2(b) and GIR 3(b), but decided, rather unconvincingly, against this approach.

In a 2000 ruling, NY F86118, CBP offered a concise but analytically hollow explanation in support of GIR 4. Here CBP invoked GIR 4 to classify under heading 9303 a device that launches dog training items, such as bird decoys, using .22 calibre blank ammunition, noting as justification the lack of any heading or subheading that identifies the 'Dog Training System either by name or function'. A deeper reanalysis of this product may, indeed, confirm that CBP correctly applied GIR 4, but the ruling, as written, lacked persuasive power.32

Reliance on GIR 4 was perhaps misplaced in HQ 966057, a 2003 ruling in which CBP classified vinyl-coated electrically conductive fabric of metallized yarns under heading 5809. CBP initially identified three potential headings, which suggested resolution under GIR 3, but, per GIR 1, two of the headings were eliminated, leaving 5809 as the sole prima facie heading. However, CBP's apparent disregard of GIR 2(b) resulted in the erroneous decision to avoid GIR 3 and instead apply GIR 4. Had CBP properly invoked GIR 2(b), two additional prima facie headings would have been identified (for the vinyl lamination in Chapter 39, and the polyester yarn in Chapter 54) and then the appropriate heading would have been reached under a GIR 3 analysis.

CBP invoked GIR 4 to select heading 4412 in a 2017 ruling, NY N282452. CBP appears to have disregarded the plain language of several headings, including 4409, 4412, 4418, and 4421. The wooden decking panels, as described, would appear to fall, prima facie under GIR 1, within the scope of headings 4409 ('Wood ... continuously shaped ... along any of its edges, ends or faces, whether or not planed, sanded or end-jointed') and 4412 ('Plywood, veneered panels and similar laminated wood'). One may also argue that heading 4418 ('Builders' joinery and carpentry of wood') casts a net broad enough to capture these decking panels under GIR 1. Presuming, though, for the sake of argument that none of these headings are found to be viable under GIR 1, GIR 1 nonetheless would bring us to a viable prima facie basket provision: heading 4421 ('Other articles of wood'). The panels appear sufficiently worked such that they are 'articles'. As discussed in section 3.4.2 supra, GIR 4 cannot be invoked when a basket provision is identified, prima facie, under the authority of GIRs 1, 2, or 3. Perhaps a more fulsome examination by CBP would have revealed a defendable reason to apply GIR 4.

4.2 US Binding Rulings Susceptible to Potential Analysis Under GIR 4

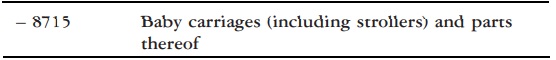

We now review two rulings (not included in Table 1) that, although not formally premised on GIR 4, involve products that may seem to be good candidates for resolution under GIR 4. In NY N006338 (12 February 2007), CBP identified heading 8716 as the appropriate provision for a relatively new consumer product known as a 'pet carriage'. The NOAD does not define a pet carriage but a simple web search reveals many examples of this product. This ruling lacks any GIR-based reasoning, so we must provide our own interpretation of CBP's analysis. CBP noted that the pet carriage 'resembles a baby stroller in appearance, featuring a fabric carrier that encloses the pet, a metal frame with handle, and wheels.' Hence a pet carriage evidently shares many characteristics with a baby carriage – the similarities are so self-evident that a reasonable person may decide that a pet carriage is irrefutably akin to a baby carriage and, therefore, is classifiable under heading 871533:

Comparing a pet carriage with a baby carriage would certainly seem a rational kinship assessment in the context of GIR 4 – but kinship is limited to GIR 4, and we know that GIR 4 can never be our starting point. Every HS analysis must unfailingly begin with GIR 1. A pet carriage clearly is not a baby carriage under a GIR 1 terms-of-the-heading analysis, but is there any other heading that captures this product, prima facie, under GIRs 1 or 2? CBP correctly determined that heading 8716 is the only potential prima facie heading:

Because a pet carriage answers, per GIR 1, exclusively to the language of heading 8716 between the semicolons – i.e. 'other vehicles, not mechanically propelled' (which, as it happens, is a basket provision)34 – GIR 3 is legally inapplicable. But, more to the point, a subjective kinship analysis under GIR 4 is impossible, no matter how closely we may think a pet carriage resembles a baby carriage. Thus classification under any heading, even a basket provision as in this exercise, that prima facie describes a product per GIR 1 will always trump any attempt to use GIR 4 – regardless of how generic, bland, non-specific, broad, or intellectually unsatisfying the basket provision's language may be.35

In NY N304567 (6 June 2019), CBP classified a 'storm glass' as a barometer under 9025.80 without citing any particular GIR. A storm glass, examples of which are easily found on various websites, is a glass orb filled with a mixture of water and other ingredients that reacts to atmospheric pressure to predict changes in the weather. If an analysis of the product's relevant characteristics caused CBP to determine that this storm glass truly is an eo nomine barometer, then there is little argument that heading 9025 is applicable, prima facie, per GIR 1. But common dictionary definitions invariably describe a barometer as an instrument able to measure or record atmospheric pressure, capabilities that a storm glass lacks (although 9025 is facially neutral with regard to recording capability). For example, the NOAD tells us that a barometer is 'an instrument [for] measuring atmospheric pressure'. 36 The NOAD defines an instrument as 'a tool or implement, especially one for precision work' and 'a measuring device used to gauge the level, position, speed, etc. of something'. 37 And the ENs for heading 9025 advise that a barometer is an instrument 'for determining the atmospheric pressure'. 38 A storm glass visually indicates a relative change in pressure but it is a stretch to call it an instrument. Moreover, a storm glass lacks the capability to measure or determine atmospheric pressure, thus it is not a barometer in the context of the HS. Perhaps, then, this product ought to be treated as a composite good classified by essential character per GIR 2(b) and GIR 3(b). In the end the temptation to invoke GIR 4 must be resisted, even though the storm glass appears to share an obvious kinship with a barometer.

5 JUDICIAL OPINIONS IMPLICATING GIR 4

Judicial attentiveness to GIR 4 is limited. Courts have not explored the fundamental nuances of the rule to any extent that could be relied upon as precedential legal guidance. Indeed, the caselaw record across different jurisdictions regarding GIR 4 is uniformly disappointing in its lack of meaningful analysis, a state of affairs that forces a practitioner to form his or her own opinion about how the rule ought to be applied. Nonetheless, in the interest of a thorough examination of GIR 4 we now review a sampling of cases from several jurisdictions in which the rule was mentioned.39

5.1 Australian Litigation

In a 1987 decision, Nylex Corporation Ltd and Collector of Customs, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia (AATA, or Tribunal) was tasked with classifying a rope comprising various man-made filaments.40 Customs contended that kinship under Rule 4 was applicable if the Tribunal determined the rope was not otherwise classifiable under 'item 59.04'. We see in this pre-HS case that the current GIR 4 is effectively similar to Rule 4: 'Where goods do not fall within any item, the item that applies to the goods is the item that applies to the goods that are most akin to those goods.' 41 The Tribunal refused to apply Rule 4, finding instead that the rope was classifiable by its essential character under Rule 3(1)(b).

Re Dick Smith Electronics Pty Ltd and Collector of Customs was a 1992 case in which the AATA determined the classification of various educational and entertainment-related electronic devices.42 The importer suggested that Rule 4 might resolve the matter, but the Tribunal declined to agree.

Karaoke machines were the subject of a classification dispute in a 2008 AATA decision, Fantastic Ltd and Chief Executive Officer of Customs.43 Here the Deputy President of the Tribunal chose to rely on GIR 4: 'Rule 4 requires me to classify the subject goods under the heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin [therefore] I conclude that they are most akin to those in heading 8543 [which are] much more akin than those described in headings 8519 or 8520 in whatever form.' It is fair to point out that this analysis is contrary to the methodology we present in section 3.4.1 supra.

In a 2010 decision, Trustee for the Kurowski Family Trust and Chief Executive Officer of Customs, the AATA applied GIR 4 to vitamin supplements, noting: 'We are mindful of Rule 4 of the interpretive rules set out above: in our view, even if the goods are not squarely medicines developed to treat specific diseases, their classification under heading 3004 is the most appropriate given the use to which products such as the goods are put.' 44 And in a similar vitamin supplement case, Comptroller-General of Customs v. Pharm-A-Care Laboratories Pty Ltd, the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) affirmed in 2018 the AATA's use of GIR 4.45 The Tribunal had noted in its conclusion that '[t]he present appears to be a case for the application of rule 4'. 46 Without exploring the merits of the Tribunal's decision to apply GIR 4, the FCA simply noted that 'the Tribunal did not err at law'. This case, on further appeal, went to the High Court (HC), which affirmed the FCA's decision in 2020. The HC provided a cogent treatise on the application of the GIRs, particularly with regard to the legal notes relevant to this litigation. Ultimately, however, no new light of any significance was cast on GIR 4 despite the rule being mentioned at several points of the court's lengthy opinion.47

5.2 Canadian Litigation

In IEC-Holden Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, a 1992 decision by the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT, or Tribunal), both the importer and the government argued in favour of using GIR 4 to resolve the classification of hydraulic stabilizers for railway rolling-stock.48 The importer claimed that '[a]s their principal function is to stabilize, that is to control resonant rocking, the goods in issue therefore fall within the meaning of tariff heading No. 84.79 ... in accordance with Rule 4'. In contrast, Customs 'asked the Tribunal to apply Rule 4 [because] shock absorbers [of 86.07] are the goods to which the hydraulic stabilizers are most akin.' The Tribunal agreed with 'both parties as to the relevance of Rule 4', deciding in the end 'that hydraulic stabilizers are more properly classified under heading No. 86.07.'

Plastic fishing tackle boxes were under review in John Martens Company v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, a 1993 decision by the CITT that relied, for better or worse, on GIR 449:

The Tribunal is unable to classify the goods in accordance with the first three Rules. As it considers the fishing tackle boxes in issue to be most akin to tool boxes organized into various compartments and not designed to accommodate a particular item, then, pursuant to Rule 4 of the General Rules, it classifies them as the tool boxes would be classified. As such tool boxes made of plastic would be classified in heading No. 39.26, so too would the fishing tackle boxes.

A 1993 decision, Wet Vest Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, addressed the classification of 'a specialized flotation device used for rehabilitation therapy'. 50 Customs claimed that the product 'is a unique item that is not specifically referred to in any of the tariff headings, and is not prima facie classifiable under two or more headings', and therefore GIR 4 controlled the decision. The Tribunal agreed that a kinship determination under GIR 4 was appropriate to resolve the dispute.

Coloridé Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue was a 2000 case that decided the classification of a product comprising 'small tufts of synthetic material, being nylon, which are arranged in such a manner as to imitate locks of hair, of different colours'. 51 The importer 'argued that the goods in issue should be classified ... based on Rule 4 [because] the goods in issue are unique [and] cannot be classified according to Rules 1, 2 and 3'. The importer further argued 'that there are different ways by which kinship can be demonstrated, including through the description of the goods, their character or their purpose'. The importer's kinship argument was evidently persuasive, as the Tribunal agreed to invoke GIR 4.

The Tribunal's decision in a 2018 case, Le Groupe Bugatti v. President of the Canada Border Services Agency, provided a superfluous and misguided discussion of GIR 4.52 The products under review were various configurations of 'writing cases (or "padfolios")'. The Tribunal offered this analysis:

Even though applying Rule 3 suffices to rule on the present appeal, the Tribunal wishes to add the following comments concerning the application of Rule 4 [which] provides that goods that cannot be classified according to Rules 1 through 3 must be classified in 'the heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin'. The Tribunal is of the opinion that the goods in issue are more akin to writing cases ('similar containers') of heading No. 42.02 than to memorandum pads and "similar articles" of heading No. 48.20 or to calculators of heading No. 84.70. Once again, it is the essential character of the goods in issue that motivate this conclusion. The writing case in itself plays a central role in the design, marketing, functioning and utilization of the goods in issue and these characteristics render the goods in issue more akin to cases of heading No. 42.02 than to articles of any other heading. Thus, the application of Rule 4 confirms the Tribunal's conclusion that the goods in issue are properly classified in heading No. 42.02.

This analysis is problematic. The Tribunal clearly recognized GIR 3 as the controlling rule, yet it was compelled to muddy its decision by opining unnecessarily that application of GIR 4 confirmed its decision. As we discussed in section 3.3.2 supra, GIR 3 and GIR 4 are mutually exclusive rules, and follow distinctly different and independent methodologies. A kinship determination per GIR 4 is not commensurate with a determination under GIR 3, hence a GIR 4 decision cannot be used to validate a decision made under GIR 3 (and vice versa).

5.3 European Litigation

European court cases have referenced kinship on several occasions but these judgments and advocate-general opinions are similarly empty of meaningful guidance. Three examples of these cases predate the HS. In 1970 in Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Oberelbe v. Firma Paul G. Bolmann the court simply said that '[t]he question whether goods are akin one to another is to be decided on the basis not only of their physical characteristics but also of their use and commercial value'. 53 In Rolf H. Dittmeyer v. Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Waltershof, a 1977 case, the advocate general contemplated whether GIR 4 was applicable, ultimately deciding (as did the court) that it was not54:

Thus interpreted, the words 'residues and wastes derived from vegetable materials used by food-preparing industries' ... cover accurately the product here in question, and it does not ... matter whether that product is or is not 'of a kind used for animal food'. If it is of such a kind, it falls directly under Heading No 23.06. If it is not, General Rule 4 in my opinion applies, for Heading No 23.06 is then that appropriate to the goods to which the product is most akin.

And in 1985 in Telefunken Fernseh und Rundfunk GmbH v. Oberfinanzdirektion München the court noted merely that '[i]n the absence of any specific heading referring expressly to the [product], it is necessary to refer to rule 4 of the rules for the interpretation of the nomenclature of the CCT (Common Customs Tariff)'. 55 The court's decision, however, did not rely on GIR 4.

Moving ahead to a sampling of HS-era cases, the advocate general in his 1996 opinion in Ministero delle Finanze v. Foods Import Srl determined 'that interpretative rules 3 (a) and 4 do not apply to the present interpretative problem' because a basket provision was available under GIR 156:

As heading No 03.02 A, on its face, excludes Molva molva [a species of cod], and thus consigns it to the position 'Other', this is not a situation in which goods appear to be classifiable under more than one heading or sub-heading, which might be regulated by rule 3(a). Nor is it a situation in which the goods ... do not fall under any heading or sub-heading, as the position 'Other' is sufficiently capacious to accommodate Molva molva. As this species falls within one of the positions provided for in the Tariff, there is, in accordance with rule 1, no need to have regard to any further interpretative rules.

The court ultimately agreed with the advocate general, ruling that:

[s]ince the general rule of interpretation set out in point 1 [i.e. GIR 1] enables ling (Molva molva) to be classified in a specific heading of the CCT, it is not necessary to apply the rules of interpretation set out in points 3 and 4, which deal with cases where more than one heading is relevant or where there is no relevant heading.57

In a 1997 opinion, Leonhard Knubben Speditions GmbH v. Hauptzollamt Mannheim, the advocate general considered but rejected analysis under GIR 4 in favour of GIR 3(c)58:

[I]t is necessary to identify the subheading that is closest to the ... characteristics of the product ... and to its current market use [and] reference may be made to the characteristics inherent to the product and to its potential commercial use. This interpretative technique, based on the principle of analogy, is ... provided for in Rule 4 of the [GIRs] of the Combined Nomenclature [CN].

A different interpretation of the CT [Customs Tariff], based on a simple textual analysis and on a comparison with the other language versions, could have the result that goods which are similar according to composition and functions may in fact be treated differently for tariff classification purposes, even though there are no other overriding reasons to justify such difference in treatment. Consequently, the breach of the principle of equality to which I have previously referred might also, on such a construction, lead the Court to declare invalid that part of the CT the provisions of which unjustifiably treat similar products differently.

Mention ought, however, to be made of yet another interpretative key, namely that set out in General Rule A.3.(c) of the [CN], which provides that, where it is not possible otherwise to classify it, the product should be classified under the heading which occurs last among those which equally merit consideration. In the present case, the heading relating to products which are 'crushed or ground' turns out in fact to be the last of these possibilities.

The final example is Deutsche Nichimen GmbH v. Hauptzollamt Düsseldorf, a case decided in 2001.59 Although the judgment did not mention GIR 4, the advocate general referenced GIR 4 in his opinion (but, again, without providing any analytic insight about the rule), noting that 'the fact that satellite receivers may be merely similar to video tuners does not preclude their classification under the same subheading; General Rule 4 ... provides for goods to be classified under the heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin if Rules 1 to 3 cannot provide an answer.' 60

5.4 US Litigation

US courts have not been allowed the opportunity to provide any guidance whatsoever regarding kinship under GIR 4. Indeed, relative to other jurisdictions, the caselaw record shows that US courts are far less inclined to consider GIR 4 as a viable path to the correct HS heading. Not a single case, whether in the first instance or on appeal, has ever been decided under GIR 4.

In the only decision worth mentioning, a 2013 case before the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) called Wilton Industries, Inc. v. United States, the court made an offhanded and injudiciously speculative comment regarding GIR 4:

Finally, even if the subject punches could not be classified in accordance with GRI 1-3, they would correctly be classified under heading 8203 because that is the "heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin" pursuant to GRI 4, i.e. hand tools such as pipe cutters and bolt cutters, not machinery and mechanical appliances such as nuclear reactors and boilers.61

Section 5, in summary, is intended as a review of a representative sampling from several jurisdictions of the few – very few – cases that address GIR 4. It is evident that this article's examination (in section 3 supra) of the kinship methodology required by GIR 4 is in conflict with, or immaterial to, several of the courts' and tribunals' opinions, suggesting that this rule was perhaps injudiciously applied

6 CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

GIR 4 is indeed the most infrequently used GIR, as intended by the drafters of the HS. It is the only GIR that requires, without exception, a subjective analysis. Moreover, it is the only rule that requires evaluation and comparison of products outside of the HS nomenclature before the HS is ultimately consulted. And as the GIR of last-resort it is the rule we all can turn to in those exceedingly rare occasions when resolution cannot be reached under the other GIRs. But, just when a particularly baffling classification mystery appears solvable only under GIR 4, a careful reanalysis finds, more often than not, another GIR path to the decision.

Since the inception of the HS, the volume of literature accrued with regard to GIRs 1–3 is fairly extensive, whether of a binding or precedential nature such as administrative rulings or court decisions, or private sector commentaries (like this article). Thus any mysteries about GIRs 1–3 have largely been revealed. In contrast, the paper trail regarding GIR 4 is sparse, and in those infrequent instances when GIR 4 is discussed it is invariably without significant analytical insight. This article, then, is necessarily speculative because the kinship standard of GIR 4 has not been substantively tested by any administrative or judicial bodies – hence it is the reader's prerogative to accept or dismiss the interpretations presented here. The only certainty with GIR 4 is that we ought not to expect any formal administrative or judicial clarity in the foreseeable future, which means that this loneliest of rules will remain a worthy topic for further speculative examination.

Footnotes

* The author has headed trade compliance organizations in global technology, industrial, and energy companies. The opinions and interpretations expressed in this article are solely the author's, and do not reflect the views, experiences, or practices of any other person or entity. Email: m-s_58@outlook.com.

1 Previous articles in this journal have addressed the HS more comprehensively; see e.g. Izaak Wind, HS 2007: What's It All About?, 2(2) Global Trade & Cust. J. 79–86 (2007).

2 Prior to 1994 the WCO was known as the Customs Cooperation Council, but for ease of reference 'WCO' is used throughout this article.

3 World Customs Organization, The Harmonized System: 30 Years On 5 (Dec. 2018).

4 This article presents the author's admittedly US-biased perspective, formed primarily in the context of the HTSUS (Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States), but in deference to a global audience we adopt the acronym 'GIR' (General Interpretive Rules) rather than the US-centric 'GRI' (General Rules of Interpretation). Further, because meaningful administrative and judicial guidance on the application of GIR 4 is virtually non-existent, our examination of this rule is necessarily more theoretical than empirical – more theoretical, say, than a similar in-depth analysis of a well-chronicled rule such as GIR 3. The GIRs are available at, http://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/ public/global/pdf/topics/nomenclature/instruments-and-tools/hs-nomeclature-2017/2017/0001_2017e_gir.pdf?la=en (accessed 31 Jan. 2020).

5 In the US, the primary civil and criminal statutes for classification-related offenses are, respectively, 19 U.S.C. § 1592 and 18 U.S.C. § 541. Both laws prescribe financial penalties, but the criminal statute also prescribes imprisonment not to exceed two years.

6 Customs agencies use the HS provision assigned to a product as a means to administer a wide range of discrete admissibility requirements, such as those regarding public and consumer safety related, for instance, to food, drugs, toys, and vehicles; environmental protection measures; intellectual property rights (including the interdiction of counterfeit and grey-market products); and various other admissibility prerequisites.

7 Article 3, para. 1(a)(ii), of the International Convention on the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS Convention), http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/ nomenclature/instrument-and-tools/hs_convention.aspx#ARTICLE_3 (accessed 31 Jan. 2020), requires adherence to the six GIRs, but para. 2 implicitly allows each country to establish its own supplementary rules of interpretation, provided such rules do not subvert the six GIRs.

8 The HS comprises more than 1,200 four-digit headings. Inferior provisions established under each heading are called subheadings. Subheadings at the five- or six-digit level, of which there are more than 5,000, compose the extent of the WCO's nomenclature, while subheadings beyond six digits may be implemented at the discretion of each national government (ibid., Art. 3, para. 3) to serve its specific revenue, admissibility, and statistical needs.

9 Subheadings are absent from a handful of headings, thus GIR 6 is never invoked for headings such as 0410, 2705, 7111, or 9023 (unless subheadings beyond six digits are implemented in a country-specific version of the HS).

10 The suitability of a heading is factually determinable only under GIRs 1, 3, and 4. A helping rule (i.e. GIRs 2, 5, and 6) does not prescribe a classification tenet, per se, under which a heading is determined as a consequence of an examination of a product's unique characteristics (tenets such as 'terms of the heading' in GIR 1, essential character in GIR 3(b), or kinship in GIR 4). Rather, the role of a helping rule is to aid a decision under the primary rules; GIR 6, for instance, facilitates the methodology applied to decisions at a subheading level, but GIR 6 is blind to the product under review. Hence we can make a broad generalization that the GIRs serve two distinct functions related to process and substance: GIRs 1, 3, and 4 serve both of these functions by their dual design, which is to facilitate the mechanics of the classification process and, equally important, to probe and analyse the substance of a product's characteristics, whereas GIRs 2, 5, and 6 are largely disinterested in the peculiar details about the product being classified and thus exist essentially to facilitate the mechanics of the process.

11 Because the focus of this article is GIR 4, the other GIRs are discussed only as necessary to give proper context to GIR 4.

12 GIR 4 must never be allowed to become the default solution for a difficult classification problem. In truth, a practitioner, nolens volens, has little free will regarding which GIRs he or she must apply to a given analysis because it is the unique fact set – not the practitioner – that determines the decision path under the appropriate GIRs. Put another way, the GIRs are not an à la carte menu from which a practitioner, by whim or bias, can choose his or her favourite GIR (or choose to avoid a less-favoured GIR).

13 GIR 4 is the rule of last resort in the HTSUS. But in the TSUS (Tariff Schedules of the United States), which was the immediate predecessor of the HTSUS (from 1963 to 1987), an article that was not classifiable under a specific provision per General Headnote 10 (General Interpretive Rules) was classified as a 'nonenumerated product' in Part 14 of Sch. 7 under 798.0000, 798.5000, or 799.0000. These were the basket provisions for 'any articles, not provided for elsewhere in these schedules'. Rather than 'most akin', the first two of these TSUS provisions included a 'most resembling' test.

14 'Kinship' is a nominal construction of the adjectival 'akin'.

15 Note (III), GIR 4. Explanatory Notes, GIR-7 (World Customs Organization 2017).

16 New Oxford American Dictionary 35 (Angus Stevenson & Christine A. Lindberg eds, 3d ed., Oxford Univ. Press 2010).

17 Ibid., at 961.

18 In the HTSUS, Additional US Rule of Interpretation 1 (AUSRI 1) carries the same legal weight under US law as the GIRs. It provides guidance on the scope of provisions controlled by use (principal and actual), and on how parts, accessories, and certain textiles must be classified. Because classification is not determined primarily under AUSRI 1, we can consider it a 'helping' rule similar to GIRs 2, 5, and 6. Many national tariff nomenclatures include country-specific legally binding supplemental interpretive rules.

19 New Oxford American Dictionary, supra n. 16, at 1386.

20 GIR 1 requires compliance with all relevant section and chapter notes. Thus a product that is otherwise captured, prima facie, by the terms of a heading may be ultimately excluded from consideration by a legal note.

21 However, we must remember that 'for any other reason' also provides legal justification for country-specific supplemental rules (e.g. AUSRI 1) to influence the prima facie analysis.

22 See e.g. Ch. 42, Note 3(B); Ch. 89, Note 1; and Ch. 95, Note 4.

23 Note (II), GIR 4. Explanatory Notes, GIR-7 (World Customs Organization 2017).

24 Going forward we use the term 'actual product' to mean the product that must be classified, while 'similar product' refers to a product that is akin to the actual product.

25 A search for a similar product must be based on a direct comparison as opposed to a search that reaches beyond one degree of separation. In other words, ifthe product to be classified (Item A) is similar to Item B, and Item B is in some way similar to another product (Item C), it ought not be assumed that Item A is similar to Item C.

26 In some instances, however, the choices at the subheading level do not require a basket provision. See e.g. subheadings 2907.1 and 2907.2, which are the first-level (one-dash) subheading choices under heading 2907.

27 See e.g. EM Industries, Inc. v. United States, 999 F. Supp. 1473 (Ct. Int'l Trade 1998), in which the US Court of International Trade (CIT) discussed how '"basket" or residual provisions ... are intended as a broad catch-all to encompass the classification of articles for which there is no more specifically applicable subheading.' See also e.g. Sharp Microelectronics Technology, Inc. v. United States, 122 F.3d 1446 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

28 A drafting curiosity of the nomenclature is that it uses two variants of this last phrase: 'not specified or included elsewhere' and 'not elsewhere specified or included'. The latter variant is used exclusively in Chs 1–83, 94, and 96, while other chapters may use the former variant, or a combination of both.

29 It is difficult to see how the headings of some chapters (e.g. Ch. 1 or Ch. 3) could ever be subject to GIR 4.

30 There is, though, one legal note that expressly invokes kinship separate from GIR 4: Section XVII, Note 5.

31 CBP publishes non-confidential rulings on CROSS (Customs Rulings Online Search System). All rulings referenced in this article are available on CROSS, https://rulings. cbp.gov/home (accessed 29 Feb. 2020). A binding ruling issued by CBP does not expire; it remains valid unless formally revoked or modified by CBP, or invalidated by judicial or legislative action. With some exceptions, rulings are issued either by CBP's National Commodity Specialist Division (NCSD) office in New York, or by CBP's headquarters office in Washington, DC. By design, an NCSD ruling typically provides little if any analysis, in contrast to the thorough analysis generally found in a ruling issued by Washington.

33 The US added the parenthetical phrase '(including strollers)' to the HTSUS version of heading 8715. As a brief aside, is there any need to consider whether 8715 is an eo nomine heading or a principal use heading? One could argue that a baby carriage is an eo nomine compound noun. But recent US court decisions may lead one to reasonably claim that 'baby' is an adjective that 'inherently suggests a type of use' – i.e. used for carrying babies – in which case a pet carriage would be excluded from 8715 because of its clearly different principal use (as defined in AUSRI 1). The US CAFC, in GRK Canada, Ltd. v. United States, 885 F.3d 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2018), examined the nuances of 'wood screws' and 'self-tapping screws'. This precedential case blurred the lines between use and eo nomine provisions, specifically 'where the name of the tariff provision itself inherently suggests a type of use'. The court noted that although the subheading is presumedly an eo nomine provision, 'wood' implies an analytically relevant use. This new classification paradigm has been applied to subsequent court decisions, perhaps most notably in the Ford Transit Connect 'tariff engineering' case, Ford Motor Company v. United States, 926 F.3d 741 (Fed. Cir. 2019). While it is important to understand the implications of this new paradigm, the distinction between eo nomine and use ultimately is irrelevant to our pet carriage review.

34 'Vehicle' is not defined in the HTSUS, but the applicable US statutory definition found in 1 U.S.C. § 4 is sufficiently broad to encompass a pet carriage: 'The word "vehicle" includes every description of carriage or other artificial contrivance used, or capable of being used, as a means of transportation on land.'

35 The US courts (the CIT and the CAFC, as well as their predecessor courts) have consistently said that an eo nomine provision includes all forms of an article or material. Thus heading 8715 includes all forms of baby carriages, but to the prima facie exclusion of pet carriages. These courts, however, have not had the opportunity, despite more than thirty years of import transactions under the HTSUS, to provide even a scintilla of useful guidance on GIR 4. Nor have they had the opportunity to review the classification of pet carriages.

36 New Oxford American Dictionary, supra n. 16, at 134.

37 Ibid., at 901.

38 Note (C) to Heading 9025. Explanatory Notes, XVIII-9025-3 (World Customs Organization 2017)

39 The size limitations of a journal article prevent a more extensive review of GIR 4 cases from other jurisdictions.

40 Nylex Corporation Ltd and Collector of Customs [1987] AATA 582 (9 Apr. 1987).

41 Customs Tariff Act 1982 (No. 113, 1982).

42 Re Dick Smith Electronics Pty Ltd and Collector of Customs [1992] AATA 57 (19 Feb. 1992).

43 Funtastic Ltd and Chief Executive Officer of Customs [2008] AATA 528 (25 June 2008).

44 Trustee for the Kurowski Family Trust and Chief Executive Officer of Customs [2010] AATA 974 (6 Dec. 2010).

45 Comptroller-General of Customs v. Pharm-A-Care Laboratories Pty Ltd (2018) 262 FCR 449 (21 Dec. 2018).

46 Pharm-A-Care Laboratories Pty Limited and Comptroller-General of Customs [2017] AATA 1816 (19 Oct. 2017).

47 Comptroller-General of Customs v. Pharm-A-Care Laboratories Pty Ltd [2020] HCA 2 (5 Feb. 2020).

48 IEC-Holden Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, AP–91–150 (CITT) (28 Apr. 1992).

49 John Martens Company v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, AP–92–022 (CITT) (10 May 1993).

50 Wet Vest Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue for Customs and Excise, AP–92–384 (CITT) (9 Dec. 1993).

51 Coloridé Inc. v. The Deputy Minister of National Revenue, AP–99–037 (CITT) (25 Feb. 2000).

52 Le Groupe Bugatti v. President of the Canada Border Services Agency, AP–2017–020 (CITT) (13 June 2018).

53 Case 40/69, Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Oberelbe v. Firma Paul G. Bolmann, [1970] ECR 00069. Notable in this judgment is the reference to Rule 5, which was the kinship rule implemented in 1968.

54 Joined Cases 69 and 70/76, Rolf H. Dittmeyer v. Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Waltershof, [1977] ECR 00231.

55 Case 223/84, Telefunken Fernseh und Rundfunk GmbH v. Oberfinanzdirektion München, [1985] ECR 03335.

56 Case C–38/95, Ministero delle Finanze v. Foods Import Srl, [1996] ECR I–06543 .

57 Ibid. (12 Dec. 1996).

58 Case C–143/96, Leonhard Knubben Speditions GmbH v. Hauptzollamt Mannheim, [1997] ECR I–07039.

59 Case C–201/99, Deutsche Nichimen GmbH v. Hauptzollamt Düsseldorf, [2001] ECR I–02701.

60 Ibid. (9 Nov. 2000)

61 Wilton Industries, Inc. v. United States, 741 F.3d 1263 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

Originally published in the June 2020 issue of the Global Trade and Customs Journal.

Check out our new Digital Magazine Get the inside scoop on the Braumiller Law Group & Braumiller Consulting Group "peeps." Expertise in International Trade Compliance.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.