Social Casino App Operator Loses Biiig in High Stakes Class Action

The roulette wheel came to a stop on Double Zero for social casino app operator Huuuge, Inc. ("Huuuge"), which, after a two-year-long string of courtroom action over claims that its apps constituted illegal gambling under Washington law, finally agreed to part with $6.5 million of its bankroll to settle a class action brought by the plaintiff, Sean Wilson ("Wilson" or "Plaintiff"). (Wilson v Huuuge, Inc., No. 18-05276 (W.D. Wash. Unopposed Motion for Preliminary Approval Aug. 23, 2020)).

Huuuge operates a smartphone social casino game app that has enjoyed widespread success with games such as "Huuuge Casino," "Billionaire Casino," and "Stars Casino" (collectively, the "Apps"). The free social gaming apps, available for download at the major app stores, offer users the chance to play virtual slot machines and other classic casino games in a casual atmosphere, open up their own virtual gaming clubs, connect with other users and otherwise try to win a bucket of virtual chips and other prizes. Huuuge initially gives users a chance to play at no cost by offering a limited number of free "virtual chips," which players can then use on Vegas-style slot machines and games of chance. Once the free chips are exhausted, however, in order to extend gameplay, users then must purchase more chips using real money, in increments ranging anywhere from $2 to $50 each. This may seem like a familiar concept to some users familiar with the "freemium" app model, which might require users to make a number of "in-app purchases" to keep playing or explore an app's more interesting features, but according to the plaintiff's allegations, there was just one problem with the apps: the social casino business model, which entices users to purchase additional virtual chips with real money violated Washington law because "all internet gambling is illegal in Washington."

That's the exact argument that plaintiff Sean Wilson brought to the table when, in April 2018, he filed a class action complaint alleging Huuuge violated Washington gambling and consumer protection laws by charging users for virtual chips for a chance to play games of chance in its app. Plaintiff himself claimed that he wagered and lost $9.99 at Huuuge's games of chance and brought the action to recover losses for all Washington users who purchased and lost chips in the apps. "Gambling," as defined under applicable Washington law, "means staking or risking something of value upon the outcome of a contest of chance or a future contingent event not under the person's control or influence...." More specifically, Wilson

alleged that the purchasable virtual chips were "things of value" under Washington law and used to obtain access to games of chance on the app. Plaintiff sought relief under Washington's "Recovery of Money Lost at Gambling Act," (RCW § 4.24.070), where users are entitled to recover certain illegal gambling losses from the proprietor.

For Huuuge, the next two years of litigation must have felt like one long night hunched over the same slot machine waiting for a payout that never came. Huuuge bet big early, seeking to dismiss the district court action and compel arbitration according to the casino apps' terms of use (which contained an arbitration clause). Huuuge argued that Wilson was bound by the arbitration provision because Wilson had constructive notice of the terms when he downloaded the app and had access to the terms during game play. Wilson countered that the app's terms were not conspicuous when he downloaded the app or during gameplay.

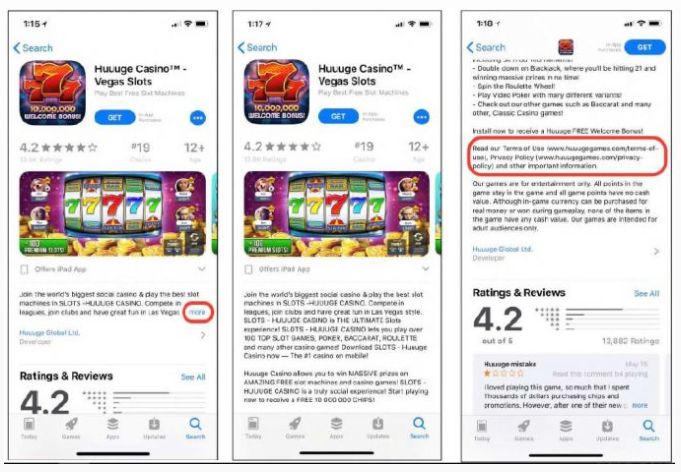

The lower court outlined how the game and terms were presented to the plaintiff at the time of downloading [See screenshot below]. As outlined by the court, if a user wanted to learn more about the app before downloading, he or she could click a link to visit the app's landing page, which included more information, including a link labelled, "More," which revealed the app's profile. According to the court, after scrolling through "several screens' worth of text," a user eventually encountered the statement "Read our Terms of Use," followed by a non-live URL that a user must copy and paste into their web browser to access the terms. Thus, at the relevant time, Huuuge did not require users to affirmatively agree to the terms before downloading or while using the app. Beyond the downloading process, users could still access the terms via the "Settings" icon within the game and navigate to the screen containing the terms, but viewing the terms in this way was also not mandatory to keep playing.

In November 2018, the Washington district court rejected Huuuge's strategy and denied Huuuge's motion to compel. The court stated that whether a website places a reasonably prudent user on inquiry notice of its terms depends on the design and content of the website or app and the conspicuousness and placement of the hyperlink to the terms. Ultimately, the district court held that Huuuge's app page and in-game settings failed to put a reasonable user on inquiry notice of the terms of use: "Huuuge chose to make its Terms non-invasive so that users could charge ahead to play their game. Now, they must live with their decision." (Wilson v. Huuuge, Inc., 351 F. Supp. 3d 1308 (W.D. Wash. 2018)).

Huuuge decided to double down on its strategy to enforce the arbitration clause in its terms, but was handed another loss in December 2019, this time in the VIP room at the Ninth Circuit. In a rather witty opinion that's much too good not to quote from directly, the court, in affirming the lower court's ruling to deny Huuuge's motion to compel, agreed that plaintiff did not have constructive notice of the terms (and arbitration clause) because he was not given adequate notice of them because "the Terms are not just submerged-they are buried twenty thousand leagues under the sea" and a user "would need Sherlock Holmes's instincts to discover the Terms." (Wilson v. Huuuge, Inc., 944 F.3d 1212 (9th Cir. 2019)). The appeals court went on: "Instead of requiring a user to affirmatively assent, Huuuge chose to gamble on whether its users would have notice of its Terms. The odds are not in its favor. Wilson did not have constructive notice of the Terms, and thus is not bound by Huuuge's arbitration clause in the Terms."

The dispute even extended outside of the courthouse when a gaming industry association, the International Social Gaming Association ("ISGA"), purportedly lobbied the Washington state legislature to amend Washington's gambling laws in a way that could foreclose Wilson's potentially winning hand. According to the motion papers supporting the proposed settlement, Wilson allegedly called Huuuge's bluff, and in a grassroots effort of his own, met with lawmakers and offered testimony before the House Civil Rights & Judiciary Committee and coordinated a letter-writing campaign to the legislators from social casino players. In the end, the bills that would have amended the gambling laws were stalled until the 2021 legislative session.

Seeing no other option but to fold, Huuuge agreed to hold settlement talks in May 2020, which culminated in a final demand which Huuuge accepted.

As part of the settlement, Huge agreed to establish a non-reversionary $6.5 million settlement fund from which the settlement class members would be entitled to recover cash payments - but not one cent of the Settlement Fund will revert to the Defendant. Huuuge also agreed to establish a voluntary self-exclusion policy which will allow players to exclude themselves from further gameplay. This policy will be prominently placed within the app, and customer service representatives will provide the link to players who request it. Additionally, Huuuge agreed to change game mechanics such that when players run out of virtual chips, they won't need to purchase additional ones to continue playing at least one more game. Recovery under the agreement will vary according to the Settlement Class Member's Lifetime Spending Amount (those with higher Lifetime Spending Amounts are eligible to recover a greater percentage back) and the overall Settlement Class Member participation levels. Thus, under the proposed agreement, Settlement Class Members in the highest category of Lifetime Spending Amounts are projected to recover gross payments in excess of 50% of their Lifetime Spending Amounts, while Members in the smallest category will likely recover gross payments in excess of 10%.

Following the plaintiff's filing of an unopposed motion to obtain preliminary court approval of the settlement, the court granted such approval on August 31, 2020. In a subsequent hearing, the court scheduled a final approval hearing for February 2021. While Huuuge didn't oppose the motion, the settlement must still be signed off by the presiding judge next year. For Wilson and the other Settlement Members who previously lost big on the casino apps and now stand to receive a payout, the sound of rain is just a few months away.

Circuit Court Puts Finishing Move on Professional Wrestler's Publicity Claims

In the latest rematch among former professional wrestler, Lenwood Hamilton ("Hamilton"), and Microsoft, Epic Games, The Coalition and Lester Speight ("Defendants"), the Third Circuit affirmed the District Court's finding that the First Amendment barred Hamilton's claim alleging the Defendants unlawfully used his likeness in a video game. (Hamilton v Speight, No. 19-3495 (3d Cir. Sept. 17, 2020) (non-precedential)). The storyline of this feud started in 2017 when Hamilton attempted to slam the Defendants, alleging that the creation and display of the character Augustus "Cole Train" Cole in the Gears of War video game series violated his right of publicity. For their defensive move, the Defendants - the video game's creator, publisher, distributor, and the Cole character's voice actor - asserted their First Amendment right to freedom of expression.

Hamilton began his career with a brief stint as a professional football player, and later went on to become a motivational speaker and to own a local professional wrestling organization, Soul City Wrestling. Soul City Wrestling was started to provide family-friendly professional wrestling entertainment, and to work with the community to spread positive messages to children about drug awareness and education. At Soul City Wrestling, Hamilton performed under the wrestling persona Hard Rock Hamilton, and purportedly portrayed a unique look with a distinctive approach to costume, dress, and appearance. Beginning in 1997, Soul City Wrestling held professional wrestling bouts at numerous venues in Philadelphia and elsewhere and Hamilton was the Soul City Heavyweight Champion. Over in the virtual world, as explained by the Third Circuit, Gears of War is a violent, cartoon-style fantasy game series, "in which members in the Delta Squad-including Augustus 'Cole Train' Cole-battle 'a race of exotic reptilian humanoids' known as the Locust Horde on the planet Sera." Players control the Delta Squad's outlandish soldiers, and their over-the-top firearms, to engage in the conflict with the Locust Horde. The voice actor for the Cole character, Defendant Lester Speight, is Hamilton's former wrestling mate (who years earlier had grappled with Hamilton under the name Rasta the Voodoo Man, and who, after one event, asked Hamilton if he would be interested in working on a shoot-'em-up videogame; Hamilton declined based on his family-friendly mindset).

Hamilton eventually saw the game for the first time, decrying that seeing the Augustus Cole character was "like looking in a mirror." In the game, the Cole character is a large, muscular, African American male and is a former professional athlete who played a fictional, football-like game called thrashball, but could be perceived as being rude, obnoxious and violent. In January 2017 Hamilton brought suit against the Defendants, asserting a right of publicity violation and related claims. In response, defendants claimed that their creative work was protected by the First Amendment. In September 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania did not buy Hamilton's angle and, in a clean finish, granted Defendants' motion for summary judgment and handed the Defendants the victory. The District Court found that the Defendants' interest in free expression outweighed Hamilton's interest in his right of publicity "because the Cole character is a transformative use of the Hard Rock Hamilton character."

The court in this instance applied the "Transformative Use Test" to balance the competing interests of the right of publicity, which protects an individual from the misappropriation of his identity, and the video game publisher's right to freedom of expression under the First Amendment. As stated by the District Court, "[u]nder the Transformative Use Test: the balance between the right of publicity and First Amendment interests turns on whether the celebrity likeness is one of the 'raw materials' from which an original work is synthesized, or whether the depiction or imitation of the celebrity is the very sum and substance of the work in question. [Courts] ask, in other words, whether the product containing a celebrity's likeness is so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant's own expression rather than the celebrity's likeness." Here, in applying the test, the District Court found that, at most, Hard Rock Hamilton's likeness was one of the "raw materials" from which the Cole character was formed, but not an in-game recreation of the Hard Rock Hamilton persona.

Although acknowledging that there are some similarities between Hamilton and the Cole character, the District Court found that Hamilton is not the "very sum and

substance of the" Cole character. Specifically, the court noted that Hamilton and the Cole character have similar physical appearances (e.g., including skin color, hairstyles, muscular builds, voices, facial features and costumes) and that Cole's character in Gears of War played thrashball for a fictional team with a name similar to the name of the professional football team Hamilton played for.

However, the court reasoned that the significant differences between the Cole character and Hamilton outweighed such similarities. For example, the avatar Cole, from parts unknown, is a soldier who fights "humanoids" in a fanciful world, while Hamilton is a former wrestler in Philadelphia with a charitable, civic-minded heart, a far cry from Cole's raison d'être, that is, to battle reptilian humanoids on a fictional planet as part of a broader military engagement related to a fictional energy source. In Gears of War, Cole is not, and was not, a wrestler, and there is no reference to "Hard Rock Hamilton" in the game. While players can dress Cole in a costume that looks like Hamilton's wrestling costume, each wears clothing and accessories that the other does not-for example, Cole wears heavy armor and carries weapons, and Hamilton's costume included a formal vest, tie, and collared shirt. Additionally, Hamilton testified that the Cole character is a heel and curses often, the complete opposite of his babyface, family-friendly Hard Rock Hamilton persona. Thus, the District Court held the Hard Rock Hamilton persona was "at most one of the 'raw materials' from which the Cole character was synthesized."

Not ready to tap out, Hamilton filed an appeal with the Third Circuit. Unfortunately for Hamilton, the match at the appeals court ended in similar defeat. In September 2020, the Third Circuit, in a brief opinion, affirmed the District Court's ruling on First Amendment grounds and declined to take away the Defendants' championship belt, noting that "[i]f Hamilton was the inspiration for Cole, the likeness has been 'so transformed that is has become primarily the defendant's own expression'".

With two defeats in two different courts, it appears Hamilton's right of publicity claims are pinned for good.

Golf Entertainment Venue's Motion to Dismiss Biometric Privacy Suit Rims Out

Thomas Burlinski ("Burlinski") and Matthew Miller ("Miller") (collectively, "Plaintiffs"), former hourly employees of Topgolf USA Inc. ("Topgolf"), stepped onto the green to bring a proposed class action suit against Topgolf for alleged violations of the Illinois Biometric Privacy Act ("BIPA") (Burlinski v. Topgolf USA Inc., No. 19-06700 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 3, 2020)). Specifically, Plaintiffs alleged that their fingerprint data, as well as the data of other employees they seek to represent as a class, was collected by Topgolf before and after every work shift without their consent and disclosed to a third-party vendor in violation of BIPA.

Topgolf is a company that operates driving range/sports bar facilities across the country. Burlinski worked for Topgolf for a few months as a bartender in 2017 and Miller worked various positions during 2017, 2018 and 2019. In lieu of last century's analog time cards, Topgolf allegedly used a biometric time tracking system to collect and retain employees' fingerprints each time they clocked in and out of work to verify their identities, and thereafter shared such fingerprint data with a third party vendor. Burlinski asserts that Topgolf never provided him any written disclosures about the collection, retention, use, or disclosure of his fingerprint data; similarly, Miller claims that Topgolf never provided him written disclosures until nearly two years into his employment. Both plaintiffs alleged that Topgolf never obtained their consent before collecting their fingerprints in the first place. Arguing that Topgolf's biometric collection practices veered off the cart path, Plaintiffs filed their initial complaint in Illinois state court in March 2019, alleging, among other things, multiple violations of BIPA concerning the allegedly wrongful collection, retention and disclosure of their fingerprint data.

In 2008, to regulate and safeguard the use of biometrics in transactions and protect consumers from the threat of privacy harms, Illinois passed BIPA, 740 Ill. Comp. Stat. 14/1 et seq., which sets forth disclosure, consent, and retention requirements for private entities that collect, store, and disseminate biometric data. Section 15(b) of BIPA, regulates the collection, use, and retention of a person's "biometric identifiers" or "biometric information." It requires collectors of biometric identifiers to, among other things, obtain the written informed consent of any person whose data is acquired. The statute contains certain exemptions for entities regulated under other statutory regimes. Under BIPA, anyone "aggrieved" by a violation of the Act may bring a civil action against the alleged offender. And because BIPA allows for a private right of action, Illinois is the center of biometric privacy-related litigation, including a myriad of suits filed in recent years against employers that have used biometric timekeeping devices without obtaining the requisite consent.

Fingerprint data is considered a "biometric identifier" under BIPA, and Plaintiffs' claims focused on three separate sections of BIPA: (i) Section 15(a) requirement for companies to maintain a public schedule of retention and destruction before collecting biometric data; (ii) Section 15(b)'s requirement for companies to obtain written consent before collecting biometric data; and (iii) Section 15(c)'s requirement for companies to obtain written consent before disclosing biometric data to third parties. Checking the scorecard, Burlinksi and Miller alleged five BIPA violations and sought statutory damages of $5,000 per reckless violation, plus attorney's fees.

Preferring to play on a different course, Topgolf removed the matter to federal court in October 2019 and filed a motion to dismiss. In its defense, Topgolf argued that the BIPA claims were preempted by the Illinois Workers' Compensation Act and, even if not, were time-barred under various statutes of limitation. Plaintiffs countered that the case should be remanded back to state court on procedural grounds. In a mixed ruling, the Illinois district court refused to dismiss the complaint. Let's break down the court's opinion one stroke at a time.

On the front nine, the court considered the question of remand teed up by the parties. Here, the court denied Plaintiffs' request to remand the action back to state court, finding that Topgolf had grounds for removal to federal court based on minimal diversity of citizenship and based on Topgolf's estimate of the potential for an increased class size that would surpass the $5 million amount-in-controversy requirement under the Class Action Fairness Act's ("CAFA"). However, the court dismissed, without prejudice, and remanded Plaintiffs' Section 15(a) BIPA retention claim to state court. The district court followed the flagstick placed by the Seventh Circuit earlier this year in a ruling which held that Section 15(a) claims related to the requirement that entities possessing biometric data maintain a publicly available data retention policy do not present a concrete and particularized injury necessary for standing in federal court.

On the back nine, the court considered the main portion of Topgolf's motion to dismiss. Here, the court rejected Topgolf's argument that the Plaintiffs' BIPA claims were preempted by the Illinois Workers' Compensation Act. Finding other Illinois state court decisions on the issue persuasive, the district court easily chipped away Topgolf's argument, concluding that the Workers' Compensation Act does not preempt BIPA claims in the employment context ("[F]rom a purely common-sense standpoint, it seems clear that biometric privacy violations are simply a bad fit for the types of injuries typically contemplated by the Workers' Compensation Act, which, at the end of the day, is meant to provide 'financial protection to injured workers'"). Lastly, the court ruled that the Plaintiffs' claims were not time-barred. Even though BIPA does not specify any limitations period, the court rejected Topgolf's argument that shorter limitations periods should apply to BIPA, instead applying the state's five-year catch-all limitations period to the Plaintiffs' BIPA claims.

With the main portion of the case staying in federal court, the Plaintiffs did not seem to have the touch with their wedge to backspin the litigation to state court. After surviving procedural defenses, the Plaintiffs will still need to drive their BIPA claims on the merits if they hope to settle the score.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.