A leveraged build-up (LBU) can best be described as the consolidation of an industry financed with borrowed funds accomplished by the formation or acquisition by an investor group of a platform company followed by the acquisition of multiple companies engaged in the same line of business as the platform company. When executed properly, the build-up creates a consolidated entity that is more profitable than were the individual components. Economies of scale become available through increased purchasing power and elimination of redundant costs (executive salaries, rents, accounting functions, etc.).

LBUs present many issues common to more traditional cash flow or asset-based financings. In addition, they also present unique challenges. This article describes some

of those issues and presents one or more ways to address them.

Deal Structure

Venture capital firms structure LBUs in a number of ways. Often, the deal structure will be dictated by the nature of the industry being consolidated.

A typical, and quite simple, structure involves the formation of an entity that acquires the assets (subject to certain liabilities) of the platform company. That acquisition is followed by subsequent add-on asset acquisitions. Each of the add-on acquisitions is consummated by the same entity that consummated the initial acquisition of the platform company.

From the lender’s perspective, the foregoing structure presents few legal issues. The

lender will make loans available to the new entity, which uses the loan proceeds (together with equity contributions and subordinated debt proceeds, where applicable) to purchase the assets of the platform company. Additional loan proceeds are used to consummate the add-on acquisitions. The lender may require that the borrower be owned by a holding company that pledges the borrower’s equity securities as collateral for the senior loans. Exhibit 1 depicts this structure.

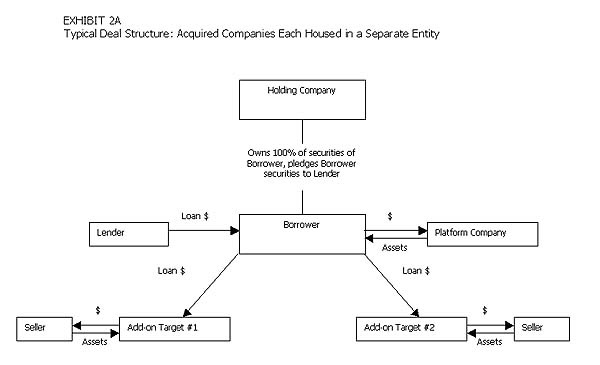

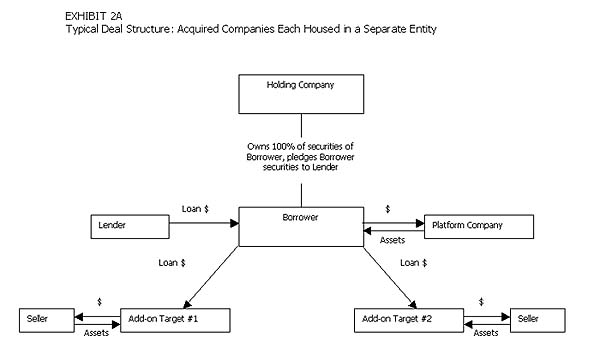

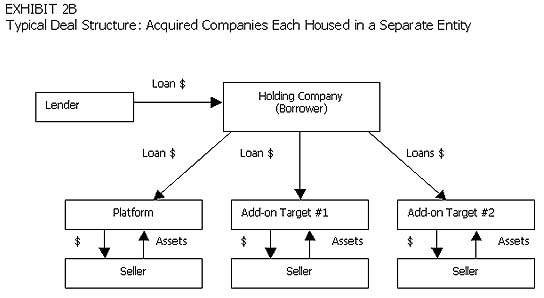

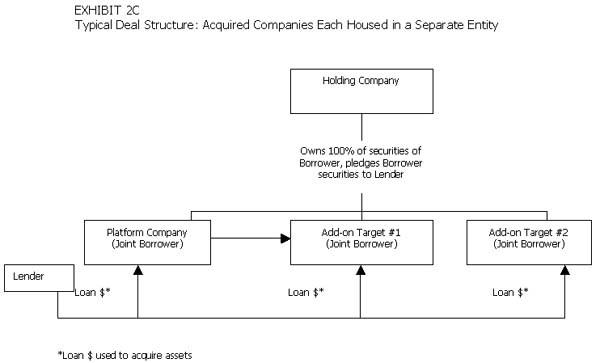

In contrast, when consolidating an industry in which the companies being acquired may be subject to unknown liabilities or risk arising from environmental, regulatory, or litigation issues, the venture capital firm will want each acquired company to be housed in a separate entity so that the consolidated assets are not subjected to the liabilities of each newly acquired business. Exhibit 2 depicts three variations on this structure.

The structures depicted in Exhibit 2 involve issues not presented by the cleaner structure depicted in Exhibit 1. Each of the structures in Exhibit 2 presents fraudulent-conveyance risk because the lender (who will acquire liens upon the assets of the platform and each add-on target) may, if the companies as a whole are not performing, find itself looking to the assets or entity value of a healthy company to satisfy the debts of an under-performing company. Whenever the economics of a deal require a lender to look to the assets or entity value of a healthy member of a consolidated group to compensate for the inability of a sibling to pay its debts, the unsecured creditors of the healthy company are likely to assert fraudulent-conveyance defenses in response to the lender’s efforts to realize upon the assets or entity value of the healthy company.

In Exhibits 2A and 2B, entities other than the borrower (add-on targets 1 and 2 in Exhibit 2A and the platform and each add-on target in Exhibit 2B) will use loan proceeds. In those cases, the lender will insist upon receiving collateralized loan guaranties from the non-borrower entities that ultimately receive the benefit of loan proceeds. Upstream guaranties are a red flag for the fraudulent-conveyance issues discussed above.

The examples in Exhibits 1 and 2 represent only a fraction of the possible deal structures for LBUs. Usually, the venture capital firm asks lenders to provide the most flexible structure possible. A truly flexible structure will permit add-on acquisitions to be consummated in the form of an asset acquisition, a stock acquisition, a merger, or any other type of business combination. Lenders can work with their counsel to minimize, but rarely alleviate, the fraudulent-conveyance risks described here. Lenders engaged in financing LBUs should understand that fraudulent conveyance risks exist.

Defining Permitted Acquisitions

As part of the loan documentation for an LBU, the lender and the borrower will need to agree upon the circumstances under which add-on acquisitions can be consummated. The loan documentation must answer three questions:

- What information must the borrower provide to the lender about the target of the add-on acquisition, and when must that information be provided?

- What substantive conditions must be satisfied before an add-on acquisition is consummated?

- What additional loan documentation must be signed in connection with the consummation of an add-on acquisition?

What Information Must the Borrower Provide to the Lender About the Target of the Add-on Acquisition, and When Must That Information Be Provided? Most LBU credit agreements provide that the borrower must provide the lender with a variety of information about the target of the add-on acquisition at least a specified number of days before the proposed closing of the add-on acquisition. While the extent of the necessary information and the number of days prior to the closing that it must be produced will vary based upon the nature of the underlying business, most credit agreements contain fairly general statements about the type of information that is to be delivered. A credit agreement might provide, for example, that the borrower must provide the lender with the results of the borrower’s completed due-diligence investigation, which should include, without limitation, environmental audits, historical and pro forma financial statements, and accounting reviews. In addition, most LBU credit agreements require that all of the materials produced by the borrower shall be "in form and substance satisfactory to the lender." Many borrowers will object to the clause set forth in the preceding sentence, arguing that the presence of such a clause gives the lender the ability to approve or disapprove each proposed acquisition even though the intent is that the lender’s consent is not necessary as long as the target of the proposed add-on acquisition satisfies certain substantive parameters. Nevertheless, such a clause is not uncommon.

What Substantive Conditions Must Be Satisfied Before an Add-on Acquisition Is Consummated? The typical LBU credit agreement will include certain substantive conditions that define those add-on acquisitions that can be consummated without the consent of the lender and those add-on acquisitions that will require the consent of the lender. Typical conditions include requirements that: (a) the "total consideration" (which shall include all cash payments, assumed liabilities, non-compete payments, earn-out payments, and similar payments) must be below a specified amount, (b) the target must be in the same general line of business as the borrower, (c) after giving effect to the add-on acquisition, the borrower must be in compliance with all financial covenants and all other covenants contained within the credit agreement on a pro forma basis, (d) the target must have had positive cash flow for the preceding 12 or 24 months, and (e) the venture capital company shall have contributed additional equity to the borrower(s) in an amount equal to a specified percentage of the total consideration to be paid for the target. Once again, the requirements will vary with the nature of the underlying business.

What Additional Loan Documentation Must Be Signed in Connection with the Consummation of an Add-on Acquisition? The typical LBU credit agreement will specify the additional documentation to be signed and delivered at the time of closing of the add-on acquisition. If the add-on acquisition involves the creation of a new subsidiary of the borrower, depending upon the deal structure, the new subsidiary will be required to execute documents that make it a borrower under the credit agreement or that provide for its guarantee of the obligations under the credit agreement. Regardless of the structure of the deal, the borrower will be required to deliver documents (including Uniform Commercial Code [UCC] financing statements) to provide the lender with a perfected security interest in the assets (and usually the equity securities) of the target. The borrower will also be required to disclose, with respect to the target, matters that would have had to have been disclosed on the schedules to the credit agreement and the other loan documents had the target been a part of the borrower when the credit agreement was originally executed.

Proposed Cost Reductions

In the typical LBU, the lender commits to lend funds in an amount not to exceed a specified multiple of the trailing 12month earnings before interest, taxes and depreciation (EBITDA) of the borrower. When an add-on acquisition is to be consummated, the borrower will ask that the trailing 12month EBITDA of the target be included for purposes of determining the maximum amount of available loans. Moreover, the borrower is likely to ask the lender to gross up the target’s EBITDA by an amount equal to the cost savings expected to be realized with respect to the target. For example, (a) if the target has EBITDA of $500,000 for the preceding 12month period; and (b) if during that 12 month period the target paid $100,000 to its chief executive officer and $50,000 to its landlord; and (c) if by virtue of the build-up the CEO will be terminated and his or her functions performed by the platform company’s CEO and the former office space of the target will be abandoned and the functions previously performed there will be consolidated with the existing office space of the platform company, then the borrower will want the lender to advance the specified multiple times $650,000 rather than $500,000. Lenders are usually willing to consider add-backs of the type described here but usually require the credit agreement to provide that add-backs are the sole discretion of the lender.

Let’s assume that the lender approves the add-backs of $150,000 described above and additional add-backs of $90,000 for marketing expenses that will purportedly be eliminated, thus resulting in total add-backs of $240,000. During the 12month period after consummation of the add-on acquisition, the add-backs will be "rolled through." When total loan availability is calculated 1month after the closing of the add-on acquisition, the add-backs will equal $220,000 (on the theory that the actual EBITDA for the 1month period following the closing already reflects 1 month’s worth of cost savings). Two months after the closing, add-backs will be reduced to $200,000 (again on the theory that actual EBITDA for the 2 months following the closing reflects actual cost savings for that 2 month period). Each month for the remaining 10 months, the add-backs will be reduced by $20,000. At the end of the year, no add-backs are necessary for the target because actual EBITDA for the trailing 12 months will reflect whatever cost savings were, in fact, realized.

Strike The Right Balance

Some LBUs involve a small number (5 or 6) of significant add-on acquisitions. An example would be an LBU of a sector of the freight forwarding industry, where a venture capital firm attempts to consolidate freight forwarders in a geographic region. Other LBUs involve a large number (20plus) of relatively small acquisitions, for example, an LBU of funeral homes. The lender and its counsel must decide, depending upon the relative importance of each add-on acquisition, the level of legal work to be performed for each add-on acquisition.

For an LBU involving a relatively small number of significant acquisitions, the lender and its counsel might decide that each add-on acquisition is worthy of a fairly complete legal due-diligence review, followed by the preparation of a fairly complete set of loan documents. In other words, the lender and its counsel will treat each add-on acquisition as if it were a new financing transaction. By comparison, for an LBU involving a large number of relatively small add-on acquisitions, its venture capital client will view the lender as obstructionist if the lender requires a complete due-diligence review and a full set of legal documents for each add-on acquisition.

For each LBU, the lender and its counsel must define the scope of legal analysis necessary for each add-on acquisition in an effort to balance the desire of the lender to learn about, and address through documentation, potential legal pitfalls and the desire of the venture capital firm to quickly, without interference by the lender, implement its build-up strategy. Counsel may warn the lenders that anything less than a full due-diligence review, followed by the preparation of complete legal documentation—

even for the smallest add-on acquisition—could lead to adverse surprises later. Nevertheless, to adequately service their customers, lenders do take calculated risks by forgoing full due diligence and documentation.

At the outset of every LBU financing, the lender and its counsel must have a thorough conversation about the potential risks associated with the industry that is being consolidated. The lender must give its counsel clear direction about the level of legal involvement expected for each add-on acquisition. Then, counsel should prepare form

legal documents to use as add-on acquisitions are consummated. Lenders that clearly advise venture capital firms of their conditions to closing add-on acquisitions can avoid surprises and meet their borrowers’ expectations.

The lender and its counsel must understand that LBUs are different from traditional financings. As a result, the lender and its counsel must be creative to satisfy the borrower’s financing needs while still protecting the lender if the borrower fails to perform as expected.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.