- within Transport and Immigration topic(s)

OVERVIEW

A recent judgment by the EU General Court demonstrates a willingness to expand the circumstances where the right to environmental information trumps the right to protection of commercial interests. The case arose from a request by two environmental NGOs to access information held by the European Commission (Commission), originally submitted in support of the first approval of glyphosate as an active substance in agricultural pesticides1. However, the ruling has potentially far wider implications for the chemicals sector and industry generally. It:

- Renders data submitters fearful of providing information to EU institutions and agencies

- Invites market competitors to test the extent to which they may be able to access confidential information submitted by rivals

- Frustrates the work of EU and national institutions and bodies, tasked with gathering information as part of pre-marketing authorisation regimes and/or providing effective oversight - since operators will be reluctant to submit information beyond the minimum required to maintain lawful market access

A near "open season" is underway on access to document cases. Accordingly, information submitters should resist the temptation to submit more than is necessary. All documentation should bear appropriate language affirming at least a right to be consulted. Submitters should also consider putting authorities on notice of their views on the impact and potential financial harm resulting from disclosure. This case will place even more focus on the stalled procedure for the revision of the Access to Documents (ATD) Regulation2 and the form of access to information rules in sector-specific legislation.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Access to Documents Regulation

The ATD Regulation confers a right on the public to seek access to documents (as distinct from pieces of information), held by the Commission, Parliament and Council. It has also been applied to EU bodies such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). All three aforementioned institutions3 and agencies4 have faced litigation on access to documents. Litigation in this area is widespread because unsuccessful applicants for access to documents are granted an automatic right5 to recourse before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)6. Most NGOs would otherwise not satisfy the conditions for standing (locus standi) before the CJEU. Applicants for access to documents are not obliged to state reasons for an application, making the regime both a source of litigation, and a tool to gain access to materials supporting ongoing or anticipated litigation.

Article 4 of the ATD Regulation provides for a series of exceptions to protect specified "public and private interests"7 where disclosure is not permitted, including situations "where disclosure would undermine the protection of commercial interests of a natural or legal person, including intellectual property ... unless there is an overriding public interest in disclosure." This was invoked by the Commission in the Glyphosate case as a reason for non-disclosure.8

Aarhus Implementing Regulation

The Aarhus Implementing Regulation 9 provides that requests for access to "environmental information" (not necessarily in the form of specific documents) held by EU institutions or bodies are to be treated within the framework of the ATD Regulation. The definition of "environmental information" (both in the Aarhus Implementing Regulation10, at the level of EU institutions and bodies, and the Public Access to Environmental Information Directive which applies in all EU member states11) is extremely wide, covering "any information in written, visual, aural, electronic or any other material form on:

- the state of the elements of the environment, such as air and atmosphere, water, soil, land, landscape and natural sites including wetlands, coastal and marine areas, biological diversity and its components, including genetically modified organisms, and the interaction among these elements;

- factors, such as substances, energy, noise, radiation or waste, including radioactive waste, emissions, discharges and other releases into the environment, affecting or likely to affect the elements of the environment referred to in point (i);

- measures (including administrative measures), such as policies, legislation, plans, programmes, environmental agreements, and activities affecting or likely to affect the elements and factors referred to in points (i) and (ii) as well as measures or activities designed to protect those elements;

- reports on the implementation of environmental legislation;

- cost-benefit and other economic analyses and assumptions used within the framework of the measures and activities referred to in point (iii);

- the state of human health and safety, including the contamination of the food chain, where relevant, conditions of human life, cultural sites and built structures in as much as they are or may be affected by the state of the elements of the environment referred to in point (i) or, through those elements, by any of the matters referred to in points (ii) and (iii)."

Article 6(1) of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation provides that where disclosure would undermine the protection of commercial interests, there is nonetheless deemed to be an overriding public interest in disclosure if the information "relates to emissions into the environment". The term "emissions into the environment" is not defined in the Aarhus Implementing Regulation or the Aarhus Convention on which the former is based, but it is clear that information on "emissions into the environment" is a distinct subset of "environmental information". The Glyphosate case is the first to provide an analysis of the scope of this key term.

ANALYSIS OF THE GENERAL COURT'S JUDGMENT

The General Court rejected the Commission's reasons for refusing to disclose12:

- Data which concerns "the identification and the quantity of various impurities present in the active substance notified by each of the operators which took part in the procedure for the inclusion of glyphosate in Annex I of Directive 91/414"13

- "The analytical profile of batches tested": "information concerning the quantity of all the impurities present in the various lots and the minimum, median and maximum quantity of each of those impurities ..." set out, for each operator14

- "The composition of plant protection products developed by the operators which applied for the inclusion of glyphosate in Annex I to Directive 91/414 ... the exact quantities, per kilogramme or per litre, of the active substance and of adjuvants used in their manufacture [of which were] ... indicated [in the requested documents] ..."15

The Commission characterised this information as "relating to the manufacturing processes used by the various operators that notified glyphosate ... [which] would make it possible to reconstitute the manufacturing process of the active substance ...". It also noted that all of the relevant information from a toxicological perspective and as regards the effect of the active substance on human health had already been disclosed.16

There are three important stages in the General Court's reasoning:

- It shows a willingness to define the key term, "emissions into the environment" through a process of extrapolation. For each category of information which the General Court found was withheld for insufficient reasons, it concluded that it related "in a sufficiently direct manner to emissions into the environment" – a proximity test. The starting point for the General Court's analysis appears to have been that "since the active substance must be included in a plant protection product, which, it is common ground, will be released into the air, principally by spraying ..."17

- Applying the same proximity analysis, the General Court

concluded that two classes of information did not

concern "emissions into the environment":

- The "structural formulas of impurities"18

- "Methods of analysis and validation"19 of the data provided to establish the analytical profile of batches

In the latter case, the General Court explicitly articulated that the information did not contain "... information allowing the determination, in a sufficiently direct manner, of the level of emission into the environment of the various components of the active substance"20.

- The General Court confirmed that, on a plain reading of the legislative texts, Article 6(1) of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation "... requires that if the institution concerned receives an application for access to a document, it must disclose it where the information requested relates to emissions into the environment, even if such disclosure is liable to undermine the protection of the commercial interests of a particular natural or legal person, including that person's intellectual property, within the meaning of Article 4(2), first indent, of Regulation No 1049/2001"21. This is described as an "irrebuttable presumption"22.

Interpretive Approach

The General Court appears to have been influenced in its reasoning process by the fact that the Commission did not argue that Article 6(1) of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation conflicts with a "superior rule of law"23. This might be: (1) primary EU law contained in the Treaties; (2) general principles of EU law developed through case law (such as the protection of business secrets); (3) rights articulated in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU; or (4) undertakings by the EU in international law (aside from the Aarhus Convention)24.

The General Court expressly considered the impact of Articles 16 (freedom to conduct a business) and 17 (right to property) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU, as well as Articles 39(2) and 39(3) of the WTO TRIPS Agreement (protection of commercially valuable information from public disclosure). It did not consider other material superior rules of law (aspects apparently not raised in argument) such as Article 339 of the TFEU (the obligation on institutions of the Union "not to disclose information of the kind covered by the obligation of professional secrecy, in particular information about undertakings, their business relations or their cost components") and Article 41 of the Charter (the right to "good administration", which includes "respecting the legitimate interest of confidentiality and professional and business secrecy").

In any event, the aspects considered by the General Court were examined only as an aid to interpretation of secondary EU law (the confidentiality provisions in Directive 91/414, the ATD Regulation and the Aarhus Implementing Regulation). The General Court was not prepared to undertake what it characterised as "disapplying a clear and unconditional provision"25 of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation - the Article 6(1) deemed overriding public interest. In a striking assertion, the General Court stated, regarding the confidentiality provisions in Directive 91/414, that it "suffices to note that the existence of such rules cannot rebut the irrebuttable presumption arising from Article 6(1)".26

A preferable approach would have been to interpret the relationship between the Aarhus Implementing Regulation and the confidentiality provisions in Directive 91/414 in a consistent manner, acknowledging the clear (sector-specific) legislative intention to protect certain information from disclosure. The Court of Justice has shown a receptiveness to this general approach in its review of the relationship between the (specific) EU regime on Emissions Trading and the (general) access to environmental information regime in Case C-524/09 - Ville de Lyon. The deemed public interest in Article 6(1) would remain applicable in situations where the legislator has not provided regime-specific rules on the sharing and protection of confidentiality.

Validity of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation

Having taken the interpretive approach summarised above, the General Court did not look at superior rules of law in order to assess the validity of Article 6(1) so that it might annul it if necessary. Arguably, the issue of validity with primary EU law is a matter of public policy given that the limits of access to environmental information are at issue. It was apparent, on the facts before the General Court, that the scope of Article 6(1) of the Aarhus Implementing Regulation has implications which go far beyond the world of agricultural pesticides, even if the immediate impact concerns that sector. The matter was therefore a strong candidate for being raised by the General Court of its own motion.27

Implications

The expansive approach to the definition of "emissions into the environment" suggested by the General Court goes beyond the mandatory disclosure of information on an actual release itself - which is more amenable to consistent application. The approach suggested by the General Court - inviting disclosure of technical information which defines the manufacturing method and compositional properties of a product - reflects a more "catch all" approach. Since "emissions into the environment" is a subset of environmental information, it cannot cover information relating to any presence or exposure (or the possibility thereof) in the environment or parts hereof. All substances enter the environment at some time during their life cycle. This leads to the conclusion that the definition must be narrowly construed if the exceptions to disclosure are ever to be applicable.

Next Steps

The Commission is understood to have decided to appeal to the Court of Justice.28 Industry stakeholders would also be able to intervene in these proceedings if they are directly affected by the judgment of the General Court29 and would be well-advised to do so given the potential commercial ramifications. EU member states may also intervene and have an interest in so doing given that the same issues arise in the context of the Public Access to Environmental Information Directive.

Appeals do not have automatic suspensory effect30 (the General Court's judgement would stand, pending a decision on an appeal) but an application for interim measures31 (suspending the General Court's judgment) may be made. The threshold test for interim measures is essentially that the applicant must prove: (i) urgency; (ii) generally, the establishment of a prima facie case; and (iii) that the balance of the parties" interests in the case requires interim measures (a proportionality test). The first of these is often the biggest hurdle because the CJEU's case law requires that interim measures may only be granted to prevent serious and irreparable damage to the party requesting them, (i.e. the decision on the matter cannot await an outcome in the main proceedings - which may take several years). The CJEU has also taken the approach that while a purely financial loss is not irreparable (since damages would remedy this), irreversible damage to market share could be sufficient to demonstrate urgency. Finally, a request for an expedited procedure32 is also possible, and if granted, exceptionally, can cut down the time it takes to conclude an appeal to less than six months.

Footnotes

* Case T-545/11 - Stichting Greenpeace Nederland and PAN Europe v Commission.

1 Inclusion in Annex I to the now repealed Directive 91/414 on Plant Protection Products.

2 Regulation 1049/2001.

3 See, for example, Case T-190/10 - Egan and Hackett v Parliament; T-561/12 - Jürgen Beninca v European Commission; and C-576/12 P - Juraainović v Council.

4 T-214/11 - ClientEarth and Pesticides Action Network Europe (PAN Europe ) v EFSA; T-245/11 - ClientEarth and International Chemical Secretariat v ECHA; and Case T-73/13 - InterMune UK and Others v EMA.

5 Article 8 of the ATD Regulation.

6 The CJEU is composed of the first instance General Court and the final court of appeal, the Court of Justice.

7 Recital 11 to the ATD Regulation.

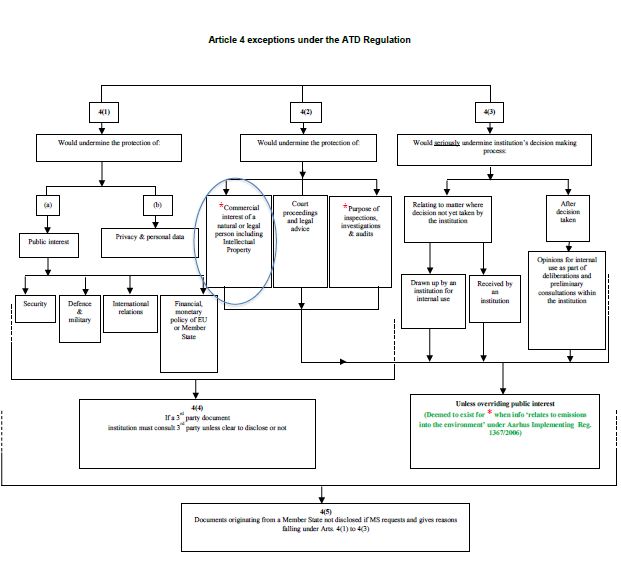

8 Paragraph 7 of the judgment. A diagram setting out the range of Article 4 exceptions to disclosure is hereby appended.

9 Regulation 1367/2006, implementing the "United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters".

10 Definition in Article 2(1)(d).

11 Directive 2003/4/EC, Article 2(1).

12 This information was included in volume 4 of the Draft Assessment Report (DAR), issued by the German rapporteur.

13 Paragraph 69 of the judgment.

14 Paragraph 71 of the judgment.

15 Paragraph 73 of the judgment.

16 Paragraph 64 of the judgment.

17 Paragraph 69 of the judgment.

18 Paragraph 71 of the judgment

19 Paragraph 72 of the judgment.

20 Paragraph 72 of the judgment.

21 Paragraph 38 of the judgment.

22 Paragraph 45 of the judgment.

23 Paragraph 44 of the judgment.

24 The decision to approve an international agreement concluded by the EU (such as the Aarhus Convention) which runs counter to a general principle of EU law may be annulled (Case C-122/95 – Germany v Council).

25 Paragraph 44 of the judgment.

26 Paragraph 40 of the judgment.

27 On this possibility see: Case T-160/08 P - Commission v Putterie-De-Beukelaer, paragraphs 58 to 60 and 67; and Case C-386/10 P - Chalkor v Commission, paragraph 64.

28 The deadline for submitting an appeal is December 18, 2013.

29 Article 56 of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union. However the timeline for so doing is only 1 month and 10 days from publication in the Official Journal of the EU (see Article 190(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice).

30 Article 60 of the Statute of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

31 Articles 160 and 190 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice. Whilst each case turns on its particular facts, there are three recent (albeit unusual) successes in the plant protection sector which are noteworthy: (1) Case T-95/09 R - United Phosphorus Ltd v European Commission, where the Court suspended a decision concerning the non-inclusion of napropamide in Annex I to Directive 91/414; (2) Case T-31/07 R - Dupont v European Commission, where the Court suspended the expiry period on the inclusion of flusilazole in Annex I to Directive 91/414; and (3) Case C-365/03 P(R) - Industrias Químicas del Vallés SA v European Commission, where the Court suspended a decision concerning the non-inclusion of metalaxyl in Annex I to Directive 91/414.

32 Articles 133 and 190 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.