- within Technology, International Law and Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

Article by Dr. Laila Haider and Dr. Stephanie

Plancich1

Introduction

The recent financial crisis was marked by the highest unemployment rates that the US has witnessed in more than 25 years. The civilian unemployment rate increased from 4.7% in November 2007 to a peak of 10% in October 2009.2 The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the number of workers displaced from jobs that they held for at least three years doubled during the period from January 2007 through December 2009 relative to the period from January 2005 through December 2007.3 Moreover, on average, these displaced workers witnessed a lower re-employment rate than those displaced in prior years, and for those that were re-employed, a smaller fraction had earnings that equaled or exceeded their earnings in the lost employment.4

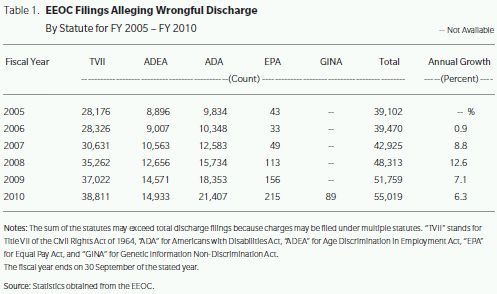

This increase in displaced workers in the US economy has been correlated with an increase in wrongful termination filings claiming discrimination. According to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), annual wrongful discharge filings citing discrimination claims grew sharply in 2008 as the economic activity worsened.5 The table below reports EEOC discharge filings, by statute, between the fiscal years 2005 and 2010. The annual growth in claims increased from 8.8% in the fiscal year ending on 30 September 2007 to 12.6% in fiscal year 2008.

A comparison of the growth in such claims with the growth in layoffs and displaced workers over the same time period implies that there was an increased likelihood during the recession that a displaced worker would bring such a claim. Specifically, wrongful discharge claims during the fiscal years 2008 and 2009 increased by 21.5% relative to the prior two fiscal years. This compares with a 14.6% increase in layoffs and displaced workers during the same time period, implying that the growth in claims surpassed the growth in displaced workers.6

Without data on the relative merits of such claims brought during the recession, no determination can be made about whether the increase in cases filed will ultimately be associated with an aggregate change in damages or settlements. For example, to the extent that a surge in filed cases is accompanied by relatively higher case dismissal rates holding all else equal, total settlements and damages may be unchanged.

While the pattern of aggregate wrongful termination filings stemming from discrimination claims has changed during the recent recession, any individual claim must be evaluated on its own merits. This claim-specific estimation of damages may also be affected by the economic downturn. To evaluate whether any claimant's alleged damages are higher or lower if termination occurred during the recession, each of the several inputs that go into the calculation of economic loss must be examined individually.

The remaining sections of this paper identify the various inputs that enter the damage calculation and evaluate how each input may be affected by the economic downturn. We consider these effects by presenting several stylized illustrations and examples; of course, the impact of the economic downturn on damage estimation in a particular case will be driven by the facts of the specific case.

Analytical Framework for the Calculation of Damages

In the damages phase of a wrongful termination case, the economic expert is tasked with the estimation of the economic loss incurred by the plaintiff as a result of the alleged wrongful termination. The estimate of alleged damages is distinct from any analysis of liability, which is often assumed for the purposes of damages estimation. The economic loss evaluated by the expert is equivalent to the plaintiff's earnings in the counter-factual or "but-for" world where the alleged wrongdoing did not occur, after an adjustment is made for "mitigation earnings," or what a similarly-situated person would have been expected to earn after termination. This analysis may involve an estimate of historical losses, and/or may include projections of earnings into the future. Depending on the horizon of the estimate, inflation and discount rates may be applied.

Information on what the plaintiff would have earned if he had not been terminated requires careful determination on the part of the expert as to what would have happened in the but-for world. Since the but-for world cannot be directly observed, the challenge for the economic expert is to construct this hypothetical world by applying the analytical tools at her disposal to the facts of the case. Similarly, the determination of appropriate mitigation earnings also requires careful consideration on the part of the expert.

Inputs in the Damage Calculation and Impact of the Economic Downturn

There are a number of inputs that enter the computation of damages in a wrongful termination claim. Each of these inputs may potentially be impacted by the economic downturn.

But-For Earnings

But-for earnings are the plaintiff's or employee's earnings in the but-for world, i.e., in the world absent termination. But-for earnings are estimated from the year of termination to the end of the loss period, which may have already occurred or may be in the future.7 But-for earnings may have several components depending on the specifics of the position from which the employee was terminated. Components may include base pay, overtime pay, bonus, and benefits.

The starting point for the determination of but-for earnings is to analyze earnings prior to and at the time of termination. Plaintiff- and employer-specific data are the foundation of any forecast of projected future earnings. To develop such a forecast, historical data regarding the nature of pay received by the plaintiff—such as whether the plaintiff received a salary or an hourly wage, received overtime pay, or was eligible for bonus income—must be collected. In addition, data on benefits and bonus payments must be collected, including information on any plan or policy governing these components.

In addition to collecting data on the components of the plaintiff's earnings, experts may also have access to historical information on the plaintiff's earnings profile. Detailed information on what the employee earned at the time of termination and in prior years will enable the expert to understand past growth in the plaintiff's earnings. Similarly, any economic analysis of but-for earnings must identify and incorporate employer- and industry-specific factors that affect employee compensation. Using these and potentially other data sources, the expert estimates how the plaintiff's earnings would have been expected to evolve over time, absent termination.

Because any model of how the plaintiff's earnings would be expected to evolve over time is affected by economic conditions facing the employer, the impact of the recession on future earnings must be considered in an analysis of alleged damages. For example, suppose that the firm from which the plaintiff was terminated revised its employee compensation plan such that salaries were frozen in the near term and criteria for bonuses became more stringent. In this case, the plaintiff's estimated but-for earnings would be lower. Holding all else equal, lower but-for earnings on account of the economic downturn imply a lower damage estimate.

Alternatively, suppose the defendant employer responded to the downturn by cutting back on a variety of costs, including the elimination of certain departments at the firm but not including an altered compensation plan for employees at the remaining departments. If we assume that the plaintiff was employed in one of the remaining departments, the plaintiff's but-for earnings may not be affected by the downturn. Holding all else equal, in this particular scenario, there would be no change in the damage estimate as a result of the recession.

In sum, how the recession is expected to affect a plaintiff's earnings in any given case depends on the employee's specific situation and how the particular employer responded to the deteriorated economic conditions. Information about the particular circumstances of the employee and employer such as the plaintiff's earnings profile, the defendant's compensation plan, and how these were affected by the downturn must be incorporated into any economic analysis of damages.

Mitigation Earnings

To derive the net economic loss incurred by the plaintiff, the estimated but-for earnings described above must be adjusted for mitigation earnings, or compensation from employment that the plaintiff either has obtained, or a similarly-situated person would have been expected to obtain, subsequent to termination. Incorporating actual or expected post-termination earnings into the analysis results in mitigation of damages to the plaintiff.

The recession may have an impact on a plaintiff's mitigation earnings, potentially affecting both the date that mitigation earnings would commence and the amount of those earnings. For example, it may be that it takes the plaintiff a longer time to find alternate employment during the recession, which means that mitigation earnings would commence later than they otherwise would. For a period of time, deteriorated economic conditions may also result in lower levels of mitigation earnings because of depressed wages and employers offering leaner benefits.

According to the BLS, 6.9 million long-tenured workers—workers who held their job for at least three years—were displaced from their jobs during the period January 2007 through December 2009.8 The January 2010 survey of displaced workers sponsored by the US Department of Labor's Employment and Training Administration indicated that 49% of these workers were re-employed in January 2010, the lowest reemployment rate since the survey began in 1984.9 Moreover, of the long-tenured full-time workers who subsequently found a full-time job, 55% had earnings that fell short of their earnings on the lost job.10 By comparison, the January 2008 displaced workers survey indicated that 45% of workers displaced during the prior time period—January 2005 through December 2007—had earnings below those earned on the lost job.11 On average, long-tenured workers displaced during the recession took a longer time to find re-employment, and for the workers who found alternate employment, a larger proportion earned less than what they did in the lost job.

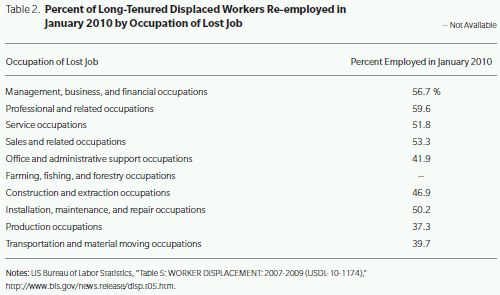

It is critical to note, however, that there is significant variation across occupations and geographies in terms of re-employment rates. Table 2 shows re-employment rates for long-tenured displaced workers by occupation of lost job. Re-employment rates were highest for workers in professional and related occupations (59.6%) and lowest for workers in production occupations (37.3%).

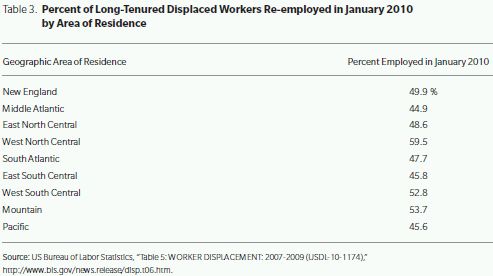

Similarly, there is also variation in re-employment rates by geographic area as shown in Table 3. Re-employment rates were highest in the West North Central geographic division (59.5%) and lowest in the Middle Atlantic (44.9%). The cross-sectional variation by occupation and geography is highlighted here to simply reinforce the notion that the facts of the case and the employee's particular situation ultimately dictate how the recession may have affected the duration of time until mitigation earnings would be expected to begin.

It is also worth noting that the figures cited above from the January 2010 displaced workers survey suggest that some long-tenured full-time workers had earnings in their new jobs that were more than those in their lost jobs. Even if the recession resulted in a delay in the plaintiff finding alternate employment, the higher earnings in the new job may outweigh the loss during that gap in employment.

It is also possible that certain personal factors dictated the plaintiff's timing of re-employment. For example, the plaintiff may have chosen to attain more schooling during the recession before searching for new employment. Alternatively, the plaintiff may have taken some time off to care for a child. Only a careful inquiry into the facts of the case can determine how the recession affected the plaintiff's mitigation earnings.

Loss Period

Another key ingredient of the damages analysis is the loss period, or the plaintiff's expected length of employment with the defendant. Put differently, absent the termination decision, how long would the plaintiff have been employed with the defendant? In each case, any analysis of alleged damages must evaluate whether the plaintiff would have voluntarily or involuntarily separated from the defendant and turned to alternate employment prior to retirement.

The recession might either lengthen or shorten the length of the loss period. For instance, the plaintiff may be less likely to switch employment during the recession if deteriorated labor market conditions in the relevant industry imply a reduced likelihood of finding a more attractive employment opportunity. Such conditions may induce the plaintiff to wish to remain with the employer longer than he or she otherwise would.

The recession may also have had a negative impact on the plaintiff's lifetime wealth, if poor economic conditions led to lower wages, lower savings for retirement, and/or a diminished value of retirement assets. Under such conditions, a plaintiff may decide to remain in the labor force longer than he or she otherwise would.

However, such an analysis must also consider that the previous employer may similarly take actions in response to the recession. For example, in an environment with poor economic conditions, the plaintiff's previous employer may downsize, making certain jobs—perhaps including the plaintiff's job—obsolete in the near term. The potential for such actions must be weighed against the expected actions of the plaintiff to assess how the recession affects the length of the loss period.

Discount Rate

A final ingredient in the calculation of economic loss resulting from alleged wrongful termination is the discount rate. As described above, the estimate of economic loss is derived from an assessment of expected future earnings. Earnings received in the future, however, are less valuable than earnings received today. This discount occurs because of the time value of money, i.e., money deposited in an interest-bearing account will grow in value over time, so that one dollar today will be worth more than one dollar in the future. To determine how much future earnings are worth today, we need to know the interest rate—referred to in calculations of present value as the discount rate—and the length of time to payment. With a discount rate r, the present value of earnings E to be received T years from now is the dollar amount that would have to be deposited today at the interest rate r to generate a balance of E after T years.

![]()

Empirically, interest rates declined precipitously during the recession. The three-month Treasury Bill rate, for example, was 5.03% in early 2007 as compared to 0.07% by October 2009.12 Holding all else equal, a lower interest rate or discount rate would yield a larger damage estimate. However, such an analysis may need to consider whether interest rates would remain at current levels during the loss period, or might be expected to increase.

Conclusion

This paper discusses how the recession may impact damages in wrongful termination cases. As emphasized throughout, the answer cannot be pre-determined. The expert must conduct a careful inquiry into the facts of the case to assess how each input into a calculation of alleged damages has been or is expected to be affected by the recession. The net effect may be that plaintiffs terminated during the recession may be entitled to lower or higher damages than had they been terminated during a healthier economic time period; the answer depends on factors specific to the plaintiff and the defendant.

Footnotes

1 The authors thank Denise Martin for her peer review and Tristan Diaz and Grant LaFarge for research assistance.

2 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, "Civilian Unemployment Rate (UNRATE)," 3 February 2012, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/UNRATE.

3 US Bureau of Labor Statistics, "WORKER DISPLACEMENT: 2007-2009 (USDL-10-1174)," 26 August 2010, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/disp.nr0.htm.

4 Ibid.

5 According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the recession began in December 2007 and lasted through June 2009. These dates coincide with the peak and trough of the business cycle respectively.

6 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, "Layoffs and Discharges: Government (JTS9000LDL)," December 2011, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/JTS9000LDL; "Layoffs and Discharges: Total Private (JTS1000LDL)," December 2011, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/JTS1000LDL.

7 The length of the loss period is an important ingredient in the analysis and is discussed in detail below.

8 US Bureau of Labor Statistics, "WORKER DISPLACEMENT: 2007-2009 (USDL-10-1174)," 26 August 2010, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/disp.nr0.htm.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, "3-Month Treasury Bill: Secondary Market Rate (TB3MS)," 9 February 2012, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/TB3MS.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.