Vistra's latest survey of 620 corporate services executives suggests some are expecting international alignment on tax, transparency and substance regulations to wane in the year ahead. But given that shared interests still exist, particularly between Europe and the US, has regulatory cooperation really peaked?

A wave of tax, transparency and economic substance regulation has transformed the corporate services industry over the last decade, subjecting global financial centres to increasingly more robust rules.

After the global financial crisis (GFC), the interests of the US and the EU aligned to drive greater transparency into private and corporate clients' financial activity, and to address a perceived tax gap.

The OECD found a willing audience among members and non-members alike for initiatives such as the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan and the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which made the world a much smaller place when it came to fighting aggressive tax avoidance and enabling information exchange. Meanwhile, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) had success in galvanising governments worldwide to strengthen anti-money laundering regulations.

Signs of a slowdown

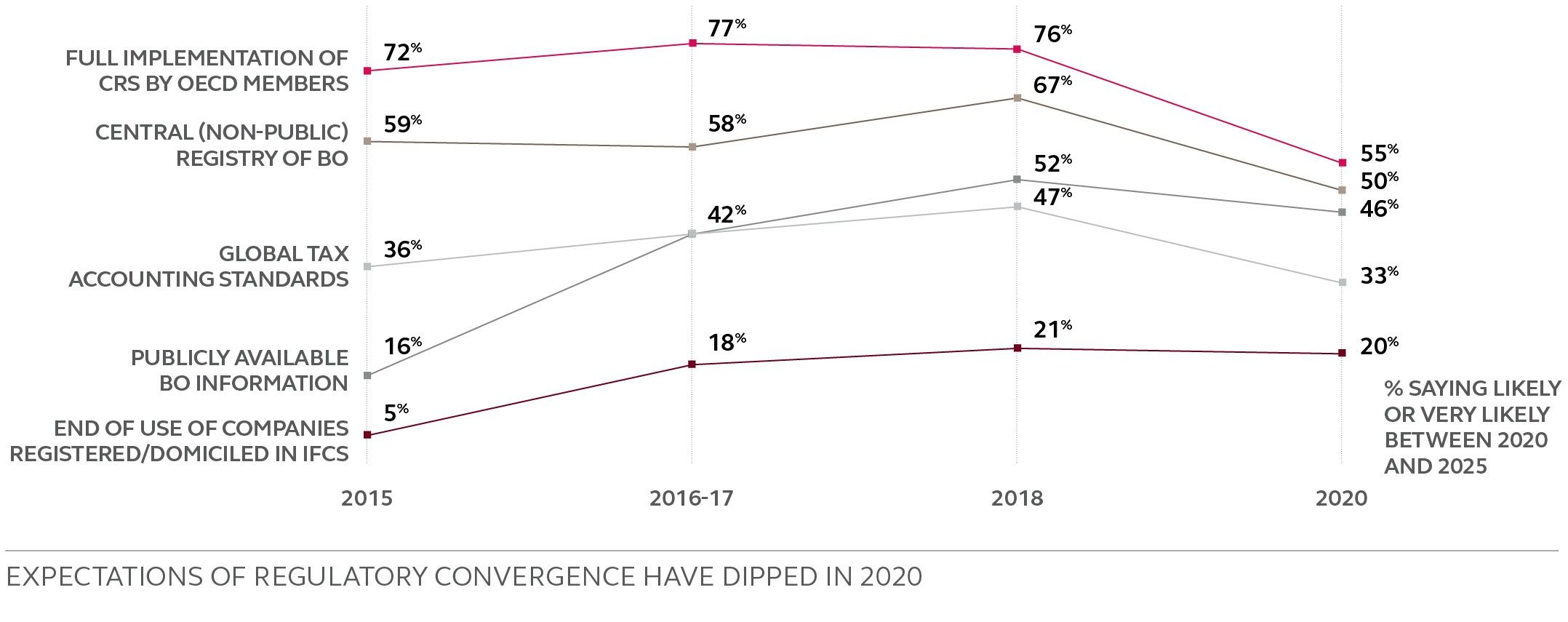

Running in parallel with this regulatory progress, Vistra's decade of research into the corporate services industry had shown expectations of regulatory convergence rise year on year - until 2020. For instance, in our 2018 study, 76 percent of respondents expected to see full implementation of CRS across OECD members by 2025, while this year, only 55 percent had the same expectation. And while 67 percent thought we were heading for global adoption of central beneficial ownership registries when surveyed in 2018, just 50 percent are expecting this today.

It is clear that we are in different times now. No one is certain that, in the teeth of the worst global pandemic in more than a century, developments on all these issues will continue at the same pace.

Many of the governments that eagerly pressed ahead with increased international cooperation may be bound to look at the deterioration of their economies during 2020 and consider whether further cooperation should take a backseat for now.

And, while Covid-19 is perhaps the dominant factor giving rise to this view, it is not the only driver. The US-China trade war, the detached relationship between the US and Europe, Brexit and the debate between EU member states as they try to adopt common responses to economic conditions, have also contributed to what some see as a diminishing resolve for international alignment.

Differences of opinion over what form international cooperation should take in areas such as information sharing, beneficial ownership registries and corporate tax rules are another reason why governments may want to slow the pace of change.

For example, the US has not signed up to the CRS and a possible change of president in November 2020 is unlikely to change that. And neither the US nor Asia seem likely to replicate the EU's legislation on what it deems to be non-cooperative tax jurisdictions.

National interest is creating friction in some BEPS discussions, too. The taxation of the digital economy is a particular sticking point between the US and Europe, where the US feels that proposed new rules would unfairly harm the interests of its technology companies.

On economic substance, the EU has deemed the Cayman Islands, a British overseas territory, to have fallen foul of its rules. The blacklist is up for review again in October 2020.

More to unite than divide

In the majority of these cases, however, the points of friction

that tend to attract most attention represent just a small part of

a bigger picture, which is one of shared underlying

interests.

Underpinning both CRS and FATCA was a shared ambition by Europe and

the US to strengthen transparency standards and rebuild trust

between the public and the banking and professional services

industries. Corporate services firms and their clients may prefer

to see a unified standard in the long term.

Meanwhile, issues such as the taxation of the digital economy

may simply prove too important for the international community to

risk halting all progress.

And in Europe, though Brexit discussions continue, the UK's

interests will usually be best served by aligning with future EU

legislation in areas such as anti-money laundering and financial

access.

The Covid-19 pandemic may also create renewed momentum for

further scrutiny of offshore business among major developed

economies. As we saw in the wake of the GFC, this agenda tends to

increase in prominence when governments feel under urgent pressure

to raise their revenues.

So, while the path of regulatory cooperation never runs smooth, and

is perhaps in for a rougher ride in the short-term due to economic

strife and political pressures, the balance of interests will

almost certainly err towards greater alignment.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.