- within Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration, Real Estate and Construction and Consumer Protection topic(s)

In February 2008, auction-rate securities (ARS) experienced widespread auction failures, and since that time, claimants have filed hundreds of related arbitration claims and lawsuits. Many investors who held ARS exited their positions when issuers restructured or refinanced their securities, and many exited or will exit positions when broker-dealers repurchase ARS under regulatory settlements. Student loan auction-rate securities (SLARS), an important auction-rate category, are a type of student loan asset-backed security (SLABS) which have their interest rates reset at frequent and periodic auctions.1 Unlike ARS issued by municipalities or by closed-end mutual funds, SLARS have seen little refinancing or restructuring activity since February 2008. Furthermore, auction-rate regulatory settlements did not cover all investors. While it is too early to know how the pending matters will ultimately be resolved, many of the ongoing matters involve student loan asset-backed securities.

These matters involve different types of parties and a range of allegations. Broker-dealers who underwrote and managed auctions are defendants in many suits where purchasers of auction-rate securities allege misrepresentations and omissions about the nature of the securities. Both corporations and mutual funds that held auction-rate securities have been sued by their own investors, who allege that they did not properly disclose their auction rate exposure. One suit alleged failure of a SLABS issuer to disclose dependence on the market for auction-rate securities. Plaintiffs seek remedies including rescission, compensatory damages, and punitive damages.

Addressing these suits requires a detailed understanding of SLABS, their underlying loan collateral, and the manner in which both the underlying loans and resulting structured products are financed. In this paper we discuss various types of student loans, focusing on loan features important to the related asset-backed structured products. We then describe the student loan industry and the financing and securitization of student loans. Finally, we explain how SLABS structures work and describe some of their interesting features.

The Student Loan Industry

In the US, students and their families pay for higher education through many sources including savings, grants, scholarships, and loans. This paper focuses on student loans, i.e., loans made specifically to fund higher education, though some education may be funded with other types of loans such as home equity or credit card loans. About 60% of students attaining a bachelor's degree use student loans to pay for their education and over $85 billion of new student loans were made for the 2007-2008 academic year. The size and growth of the student loan market are driven by factors such as the business cycle as well as demographics, enrollment, and tuition costs. In 2007, the average undergraduate borrower at a four-year institution had debt of $22,700.2

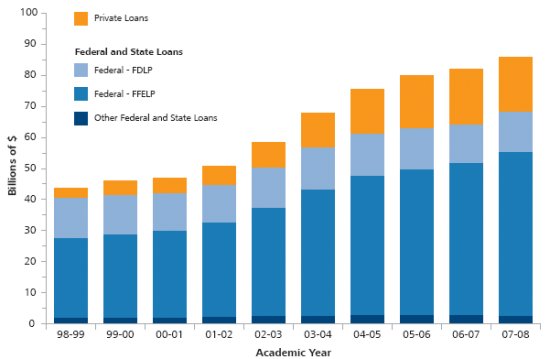

Student loans may be broadly categorized as either "federal" or "private." Federal loans comprise the majority of student loans, but private loans have become an increasingly important source of higher education funding in recent years. This is shown in Exhibit 1 below.

Exhibit 1. Loan Originations For Postsecondary Education Expenses Billions

Source: The College Board. Data in constant 2007 dollars. 2007-2008 data are preliminary.

Private Loans

Private loans, used by about 10% of undergraduate borrowers,3 differ from federal loans in several ways. Private loans may be used in conjunction with federal loans, which we describe below, and in some cases a student may even receive a single bill for both types of loans. Unlike federal loans, which are subject to maximum fixed rates and have interest rates set by regulation, private loans are generally variable rate and do not have rates set by regulation. Private loans also lack a federal guarantee protecting lenders against default (described later in this paper, beginning on p. 7) and tend to be more costly to borrowers. Private loan lenders are, however, offered some default protection in that student loans, whether federal or private, are generally not dischargeable in bankruptcy, i.e., cancelable by the court.

Federal Loans

Federal loans are made under two primary programs: the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program (FDLP or Direct Loan Program) and the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP or FFEL Program).4 The types of loans available to students and key terms of those loans, such as maximum rates borrowers may be charged, are generally the same under both programs.5 Under the Direct Loan Program, which began in 1993, students borrow directly from the Department of Education. Under the FFEL Program, students obtain a federal loan from a private lender. The FFEL Program was first established under the Higher Education Act of 1965 and was known as the Guaranteed Student Loan Program until 1992. The volume of FFELP and FDLP loans over the last decade is shown in Exhibit 1 above.6 Schools choose whether they will participate in the FFELP or the FDLP and while most schools participate in only one of the programs, some participate in both. Schools participating in the FFEL Program often have a preferred lender list, however, students may choose any lender, whether it is on their school's list or not. Preferred lender lists received significant media attention in 2007 and were subject to scrutiny by the House and Senate Education Committees, the New York Attorney General, and others. One Congressional report found that some "FFEL lenders provided compensation to schools with the expectation, and in some cases an explicit agreement, that the school [would] give the lenders preferential treatment, including placement on the school's preferred lender list."7

There are four types of loans available under these two Federal programs: subsidized Stafford loans, unsubsidized Stafford loans, PLUS loans, and consolidation loans, all of which have interest rates regulated under the Higher Education Act. Students must be enrolled in an eligible institution and meet certain citizenship and other requirements in order to qualify for these federal loans. Subsidized Stafford loans, only available to students with demonstrated financial need, do not require students to make interest payments while still in school. Unsubsidized Stafford loans are made to students who meet non-need-based eligibility requirements. These loans do require students to make interest payments while still in school, though a student may defer these until after graduation by choosing to capitalize interest, i.e., adding the interest payments to the loan balance. PLUS loans (Parent Loans for Undergraduate Students) are made either to parents of undergraduate students or to graduate students, while consolidation loans combine multiple education loans into a single loan. Stafford and PLUS loans generally must be repaid within five to ten years; FFELP consolidation loans must be repaid within 12 to 30 years.

In February 2009, the Obama administration released its proposed 2010 budget. Among other proposed changes, the administration would eliminate the FFEL Program and shift all financing of federal loans to the public sector. If approved, this would cause "sweeping changes in the way the federal government provides student loans."8 The federal government currently regulates interest rates and other terms of federal loans, and bears the majority of default risk on these loans, as we discuss below. We also discuss how the federal government gives FFELP lenders some protection against interest rate risk. Thus, from the federal government's perspective, these risks it bears under the current FFEL Program would not dramatically change if the Obama administration's budget were approved.

Industry Players

The federal government has traditionally played a role in facilitating post-secondary education. Federal loans comprise the majority of the student loan market, as shown above. In addition to the Direct Loan Program and FFEL Program, a number of other federal programs fund higher education. For example, Pell grants and Perkins loans are two important programs that help students with exceptional need pay for college.9 In the 1940s the GI Bill, formally known as the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, helped 7.8 million World War II veterans receive education or training.10

In 1972 Congress created the Student Loan Marketing Association, more commonly known as "Sallie Mae." This government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) was created to support secondary markets for student loans, as other GSEs were created to support home mortgage lending. Initially, Sallie Mae's business was fairly simple: it purchased student loans from and made secured loans to banks and other lenders.11 Over time, Sallie Mae began to issue SLABS and expanded into other parts of the student loan industry such as loan consolidation, servicing, and even college savings plans.

The government took steps to privatize Sallie Mae over time; by 2004 the privatization was complete and the company had been renamed SLM Corporation. In April 2007 SLM Corporation reached an agreement in principle to be acquired by a group led by J.C. Flowers & Company, but the Flowers group later rejected the agreement, citing the credit crisis and passage of the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007 under the agreement's material adverse effect clause. Following a lawsuit filed by SLM Corporation, the parties reached a settlement in January 2008.

Today, Sallie Mae is the largest lender and servicer of student loans in the United States, though many other lenders are also important participants. Sallie Mae is both the largest originator and holder of FFELP loans in the US and it makes private student loans as well. In 2008, the 10 largest FFELP lenders originated 69% and held 70% of FFELP loans and Sallie Mae originated 23% and held 35%, as shown in Exhibits 2 and 3 below. Other important industry participants such as Citibank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo are also seen below.

Exhibit 2. Largest Originators Of FFELP Loans, Based On New Fiscal Year 2008 Guarantees

|

|

FY 2008 Originations |

|

1. SLM Corporation (Sallie Mae |

14,266 |

|

2. Citibank, Student Loan Corp. |

6,201 |

|

3. Wachovia Education Finance Corp. |

5,128 |

|

4. Bank of America |

4,275 |

|

5. Wells Fargo Education Financial Services |

3,935 |

|

6. JPMorgan Chase Bank |

3,418 |

|

7. US Bank |

2,278 |

|

8. EDAmerica |

1,614 |

|

9. Pittsburg National Corp (PNC) |

1,269 |

|

10. Suntrust Bank |

1,092 |

|

Top 10 Total |

43,475 |

|

Total for All Originators |

63,210 |

Excludes consolidation loans.

Source: US Department of Education National Student Loan Data System.

Exhibit 3. Largest Holders Of FFELP Loans, Based On Fiscal Year 2008 Amount Outstanding

|

|

FY 2008 Amount |

|

1. SLM Corporation (Sallie Mae) |

141,499 |

|

2. Citibank, Student Loan Corp. |

31,322 |

|

3. National Education Loan Network (Nelnet) |

35,912 |

|

4. Wells Fargo Education Financial Services |

14,245 |

|

5. Brazos Group |

11,411 |

|

6. Wachovia Education Finance Inc. |

12,331 |

|

7. Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Authority (PHEAA) |

11,987 |

|

8. JPMorgan Chase Bank |

11,944 |

|

9. Student Loan Xpress |

11,097 |

|

10. College Loan Corp. |

10,447 |

|

Top 10 Total |

384,896 |

|

Total for All Holders |

406,108 |

Source: US Department of Education National Student Loan Data System.

The federal government and private lenders both play important roles in financing higher education, as do entities at the state level. Many states have established entities that perform activities such as guaranteeing FFELP loans, servicing student loans, awarding scholarships and financial support, and creating statewide educational programs. For example, the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency is one of the largest holders of FFELP loans, as shown above in Exhibit 3. It was created in 1963 by the Pennsylvania General Assembly and its mission is "to improve higher education opportunities for Pennsylvanians."12 The Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency issues SLABS directly and also serves as a guarantee agency, as we describe below.

Finally, some industry players focus only on private student loans. First Marblehead Corporation acts as an intermediary between student loan originators and investors in SLABS by securitizing private student loans (we describe securitization on p. 12). The Education Resources Institute, Inc. (TERI), which filed for bankruptcy on 7 April 2008, acted as a guarantor of private student loans. The two companies had a close business relationship including a series of agreements for securitization, loan processing, and servicing. Both the TERI bankruptcy and First Marblehead's inability to complete new securitizations in recent quarters, have had a negative impact on First Marblehead's business; its revenues for fiscal year 2007 exceeded $880 million while those for 2008 were actually negative due to fair value losses on advisory fee and residual receivables.13

FFELP Loans And The Federal Guarantee

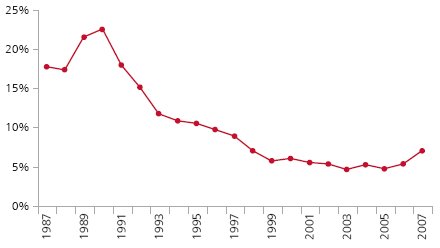

Many people speak about "federally guaranteed student loans" or "federally insured student loan securities" when referring to FFELP loans, particularly when speaking about securitized student loans. We have two primary observations about this guarantee: (1) The guarantee protects loan holders against non-payment by student borrowers—it does not directly protect interest and principal payments on SLABS. In other words, the guarantee is at the level of the underlying loan collateral—not at the level of the student loan-backed bond. (2) The student loan insurance is not directly provided by the US government; it is provided by a guarantee agency which, in turn, is reinsured by the Department of Education. To put the significance of the federal guarantee into context, Exhibit 4, below, shows historical one-year default rates on federal loans.14

Exhibit 4. One Year Borrower Default Rates For Federal Student

Source: US Department of Education. Fiscal year data include FDLP loans starting in 1995. Default rate is the percentage of borrowers who enter repayment in a fiscal year and default or meet other specified conditions by the end of the next fiscal year. 2007 rate is a draft figure.

Guarantee Agencies

The US government currently reinsures certain student loans, made under the FFEL Program, against default. Guarantee agencies insure these loans directly. If a student defaults on a loan, the loan holder may submit a claim to the guarantee agency responsible for that loan. The loan holder could be a lending institution that originated the loan, or, if a particular loan has been securitized, the holder could be a trust which owns a pool of student loans. FFELP guarantee agencies are listed in Exhibit 5 below, along with their loan repayment amounts and default rates for fiscal year 2006. As seen in Exhibit 4, the national 2006 default rate was 5.2%, but this rate varied widely among guarantee agencies, as shown below.

Exhibit 5. FFELP Guarantee Agencies

|

FFELP Guarantee Agencies |

Areas Served |

Loan Repayment Amount ($) |

2006 Default Rate (%) |

|

1. American Student Assistance |

DC, Massachusetts |

153,492,320 |

1.4 |

|

2. California Student Aid Commission/EDFUND |

California |

1,346,917,125 |

10.6 |

|

3. College Assist (formerly known as Colorado Student Loan Program) |

Colorado |

102,052,512 |

2.5 |

|

4. Connecticut Student Loan Foundation |

Connecticut |

37,999,893 |

5.1 |

|

5. Education Assistance Corporation |

South Dakota |

149,496,624 |

5.0 |

|

6,7. Educational Credit Management Corporation |

Oregon, Virginia |

170,434,131 |

4.2 |

|

8. Finance Authority of Maine |

Maine |

26,460,413 |

6.4 |

|

9. Florida Office of Student Financial Assistance (OSFA) |

Florida |

171,734,220 |

9.1 |

|

10. Georgia Student Finance Commission |

Georgia |

66,447,115 |

8.4 |

|

11. Great Lakes Higher Education Corporation |

Minnesota, Ohio, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Wisconsin |

606,730,826 |

2.4 |

|

12. Higher Education Student Assistance Authority |

New Jersey |

141,487,275 |

10.4 |

|

13. Illinois Student Assistance Commission |

Illinois |

187,504,457 |

6.7 |

|

14. Iowa College Student Aid Commission |

Iowa |

62,476,980 |

5.6 |

|

15. Kentucky Higher Education Assistance Authority |

Alabama, Kentucky |

206,516,610 |

9.2 |

|

16. Louisiana Office of Student Financial Assistance |

Louisiana |

95,155,845 |

7.1 |

|

17. Michigan Higher Education Assistance Authority |

Michigan |

185,048,091 |

5.5 |

|

18. Missouri Student Loan Group |

Missouri |

108,403,215 |

5.4 |

|

19. Montana Guaranteed Student Loan Program |

Montana |

23,477,613 |

2.3 |

|

20. National Student Loan Program |

Nebraska |

455,764,984 |

8.7 |

|

21. New Hampshire Higher Education Assistance Foundation |

New Hampshire |

32,311,157 |

2.2 |

|

22. New Mexico Student Loan Guarantee Corporation |

New Mexico |

39,349,626 |

2.8 |

|

23. New York State Higher Education Services Corporation |

New York |

366,863,946 |

5.6 |

|

24. North Carolina State Education Assistance Authority |

North Carolina |

94,593,629 |

1.5 |

|

25. Northwest Education Loan Association |

Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, Washington |

124,859,628 |

8.9 |

|

26. Oklahoma Guaranteed Student Loan Program |

Oklahoma |

134,434,707 |

7.7 |

|

27. Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency /American Education Services |

Delaware, Pennsylvania, West Virginia |

432,006,034 |

3.4 |

|

28. Rhode Island Higher Education Assistance Authority |

Rhode Island |

28,836,945 |

5.4 |

|

29. South Carolina Student Loan Corporation |

South Carolina |

56,125,710 |

1.4 |

|

30. Student Loan Guarantee Foundation of Arkansas |

Arkansas |

30 Student Loan Guarantee Foundation of Arkansas |

9.4 |

|

31. Student Loans of North Dakota |

North Dakota |

25,045,078 |

3.1 |

|

32. Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation |

Tennessee |

153,511,471 |

7.1 |

|

33. Texas Guaranteed Student Loan Corporation |

Texas |

701,219,900 |

9.1 |

|

34. United Student Aid Funds / SMS Hawaii |

Multiple |

1,814,256,171 |

4.6 |

|

35. Utah Higher Education Assistance Authority |

Utah |

72,107,440 |

2.8 |

|

36. Vermont Student Assistance Corporation |

Vermont |

19,197,430 |

2.2 |

Sources: Department of Education, FinAid, and National Council of Higher Education Loan Programs.

The 2006 default rates represent the percentage of borrowers who started repaying loans between 1 October 2005 and 30 September 2006, and who defaulted before 30 September 2007.

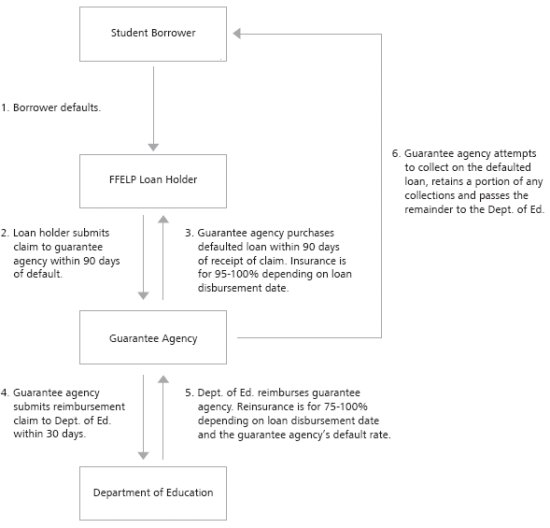

After a borrower defaults, the loan holder submits a claim to the guarantee agency for that loan within 90 days. Assuming the loan holder and the guarantee agency have followed applicable regulations and procedures, the guarantee agency will pay the loan holder a specified portion of the principal balance as well as accrued interest on the loan within 90 days of receipt of claim.15 This default guarantee percentage has changed over time due to legislation and is based on the loan's disbursement date as summarized in Exhibit 6 below.16

Exhibit 6. Guarantee Percentage Of Unpaid Principal Balance For Defaulted Loans

|

Loan Disbursement Date |

Guarantee Percentage |

|

Prior to 1 October 1993 |

100% |

|

1 October 1993 – 30 June 2006 |

98% |

|

1 July 2006 – 30 September 2012 |

97% |

|

On or after 1 October 2012 |

95% |

Sources: 34 C.F.R. § 682.401 (2008), 20 U.S.C. § 1078(b)(1)(G) (as amended by Pub. L. No. 110-84 § 303, 121 Stat. 797 (2007)).

After receiving payment for the defaulted loan from the guarantee agency, the loan holder's process is complete. The guarantee agency must then seek reimbursement from the Department of Education by submitting a claim within 30 days. Reinsurance from the federal government is for 75 to 100% for defaulted loans, based on the guarantee agency's fiscal year default rate and the loan disbursement date.17 Reinsurance rates decline as guarantee agency default rates increase; there are reinsurance "triggers" at 5% and 9% of loans in default. Exhibit 7 summarizes.

Exhibit 7. Guarantee Agency Reinsurance Rates

|

Loan Disbursement Date |

Maximum |

5% Trigger |

9% Trigger |

|

Prior to 1 October 1993 |

100% |

90% |

80% |

|

1 October 1993 – 30 September 1998 |

98% |

88% |

78% |

|

On or after 1 October 1998 |

95% |

85% |

75% |

Source: 34 C.F.R. § 682.404 (2008).

For example, since the California Student Aid Commission had a default rate of 10.6% in 2006, as shown in Exhibit 5 above, it would generally be eligible to receive reinsurance claims for 75% of loan balances for a defaulted loan disbursed on or after 1 October 1998. The South Carolina Student Loan Corporation would receive 95% of its reinsurance claims for similar loans because it had a 1.4% default rate.

In addition, the guarantee agency is obligated to attempt to collect on the loan, though the timing of this collection activity is not tied to that of reimbursement from the Department of Education. The guarantee agency retains a specified portion of any collections and submits the remainder to the Department of Education. As stated earlier, student loans are generally not dischargeable in bankruptcy. If a student defaults on a federal loan, lenders or collection agencies may garnish up to 15% of a borrower's disposable pay and intercept tax refunds or even Social Security payments.

This general description of the process following default on a FFELP loan is summarized in Exhibit 8, below.

Exhibit 8. Stylized Cash Flows Following Default On An FFELP Loan

Sources: 34 C.F.R. § 682.401; § 682.404; § 682.406; § 682.410 (2008), 20 U.S.C. § 1078(b)(1)(G) (as amended by Pub. L. No. 110-84 § 303, 121 Stat. 797 (2007)).

Special Allowance Payments

In 1969, four years after creating the FFEL Program, Congress established subsidies for FFELP loans called Special Allowance payments. These payments provide FFELP loan holders with revenues tied to prevailing market interest rates and are a participation incentive for lenders as they provide some protection against interest rate risk. When market interest rates rise, Special Allowance payments supplement the payments loan holders receive from borrowers, thus eliminating a potential concern over holding below-market rate loans.

The precise formulas used to determine these quarterly Special Allowance payments are complex and based on a number of factors, primarily the type of loan and the loan's disbursement date. In general, Special Allowance payments are based on the three-month financial commercial paper rate for loans made on or after 1 January 2000 and on the 91-day Treasury bill rate for prior loans.

For example, a Stafford Loan in repayment that was disbursed in November 2007 has a Special Allowance payment calculated as:

- the average, during the relevant three-month period, of the bond equivalent rates of three-month financial commercial paper rates,

- minus the applicable borrower interest rate,

- plus 1.79%,

- divided by four.18

If this calculated amount is negative, the Special Allowance payment is zero and for FFELP loans originated on or after 1 April 2006 loan holders must refund "excess interest" to the Education Department. Thus, from the perspective of the FFELP loan holder, FFELP loans provide either a variable market-based rate (for loans originated on or after 1 April 2006), or a minimum fixed payment from the student borrower plus a variable market-based rate (for loans originated prior to 1 April 2006).

Student Loan Asset-Backed Securities (SLABS)

Over the past two decades, securitization has emerged as a popular method of financing student loans, and proceeds from securitization are an important source of funding for both private and federal loan (i.e., FFELP) lenders. Securitization is a process in which loans made to many individual borrowers are pooled into securities backed by cash flows from these loans. Through this process, lenders may effectively sell loans to investors in student loan asset-backed securities (SLABS) and thus free up capital for additional lending. In March 2009 there were $237 billion in student loan asset-backed securities outstanding.19

Entities that issue SLABS may be divided into two broad categories: private companies, such as Sallie Mae, and state loan entities, such as the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, both described above. Through the process of securitization, a SLABS issuer can pool its own previously originated loans, loans it purchased from other originators, or a combination of the two. While most SLABS collateral consists of FFELP loans, perhaps due to the standardized nature of FFELP loans, the collateral could also be private loans or a mixture of the two. The newly issued bonds (the student loan asset-backed securities) are backed by the student borrowers' future principal and interest payments. Issuers can design structures with bonds of varying maturities, but the typical bond has a maturity from 20 to 40 years.

All types of student loan industry players have faced challenging credit market conditions over the last two years. While they continue to act as FFELP loan guarantors, as described below, at least five state loan entities have suspended FFELP lending activities since August 2007.20 The Michigan Higher Education Student Loan Authority suspended FFELP lending because "it ha[d] become effectively impossible to raise new capital," and the Massachusetts Educational Financing Authority said it had "been unable to secure funding."21 The Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency cited "recent failed securities auctions in the troubled bond market."22 Private loan lenders have pulled back as well. According to one industry observer, 45 lenders have suspended their private student loan businesses since August 2007 and after growing at a compound annual rate of 22% from 2000 to 2007, private loan origination decreased by 2% from 2007 to 2008.23 Both direct lending and securitization activity is down. Sallie Mae completed no asset-backed securities (ABS) transactions in the fourth quarter of 2008, compared with three transactions totaling $5 billion in the fourth quarter of 2007, and First Marblehead completed no securitization transactions from October 2007 to March 2009.24

In response to concerns about funding for federal student loans, on 7 May 2008 President Bush signed the Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loans Act (ECASLA) into law. The bill, which was extended for the 2009-2010 academic year, allows the Department of Education to directly purchase entire pools or participation interests in pools of FFELP loans. The Department of Education also established Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) Conduits that will be able to purchase FFELP Stafford and PLUS loans originated since 1 October 2003. If there is insufficient demand for commercial paper issued by the ABCP Conduits, the Department of Education will directly purchase FFELP loans. As of November 2008, ECASLA programs had provided almost half the financing for FFELP loans for the 2008-2009 academic year. Through this program and the Direct Loan program, the Department of Education is funding over 60% of federal loans for the 2008-2009 academic year.25

To encourage issuance of asset-backed securities, both those backed by student loans as well as other types of collateral, the Federal Reserve announced the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) on 25 November 2008. Under the TALF, US companies may obtain three-year loans if they own eligible ABS collateral. SLABS issued in 2009 are eligible as collateral for TALF loans if they have AAA credit ratings.26 While the first round of TALF loan requests did not include the student loan sector, May 2009 TALF loan requests included $2.3 billion backed by student loans.27

Example Structures

As we described earlier, SLABS issuers may be broadly categorized as either private companies or as state loan entities. We describe two example structures, one from each issuer type, and then discuss several types of common credit enhancements.

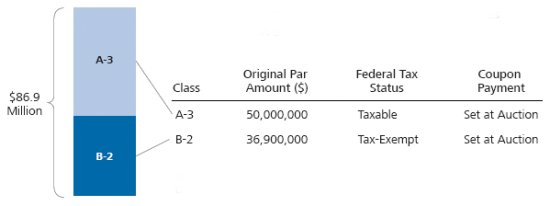

The first example structure was issued in December 2007 by the Connecticut Student Loan Foundation (CSLF), a state loan entity that primarily guarantees and originates FFELP loans.28 This deal's noteholders are entitled to a pro-rata share of the Foundation's payments made to bondholders of the same seniority (i.e., other senior notes or other subordinate notes). Thus, while this particular deal contains two bonds, other bonds issued by the foundation may affect the payments that these notes receive. Both of the CSLF bonds are auction-rate securities, but the A-3 CSLF bonds are federally taxable, while the B-2 bond is federally tax-exempt, as shown in Exhibit 9, below.29 Additionally, the B-2 notes have a conversion feature which allows the Foundation, at its discretion, to convert them from auction-rate notes to either fixed-rate or variable-rate notes.

Exhibit 9. Connecticut Student Loan Foundation Series 2007A-3 and 2007B-2

Source: Connecticut Student Loan Foundation, Student Loan Revenue Bonds, Official Statement, 5 December 2007.

The second example structure is a Sallie Mae deal issued in 2006. These bonds are backed by a pool of FFELP consolidation loans. The Sallie Mae structure contains both auction rate bonds and floating rate bonds that are tied to LIBOR. The senior bonds mature earlier than the junior bonds, which do not receive principal payments until the more senior bonds have been paid down. The three Class A-6 notes have the same priority of principal and interest payments, but the A-6A bond pays out a floating rate of three-month LIBOR plus a spread of 16 basis points, whereas the A-6B and A-6C bonds pay out rates that are set at auction. These auctions are held every 28 days, but on different days of the week for the A-6B and A-6C bonds. See Exhibit 10, below.

Exhibit 10. Sallie Mae Student Loan Trust 2006-7

Source: SLM Student Loan Trust 2006–7, Prospectus Supplement to Base Prospectus Dated 12 July 2006

Credit Enhancement Features

In addition to the direct claim that SLABS noteholders have on the student loan assets, SLABS typically have multiple credit enhancement features designed to limit the default risk on their notes. These credit enhancements are in addition to any federal or private guarantee which might be carried by the underlying loan collateral. Many other types of structured products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) feature various types of credit enhancement as well. We describe some of the most common SLABS credit enhancements.

- Overcollateralization

-

- Overcollateralization is the practice of issuing a dollar amount of securities with a lower expected payout than the expected payout from the loan portfolio backing those securities. If defaults or missed payments are greater than expected, overcollateralization prevents losses from impacting noteholders up to a certain point. For example, if a pool of student loans is expected to pay out $105 million over its life, the issuer might only sell $100 million of notes. After issuance, market participants often examine a structure's "parity ratio" to gauge how well-funded a SLABS deal is. The parity ratio is calculated as the outstanding principal and capitalized interest of the student loans divided by the amount outstanding of the notes, or assets divided by liabilities. A parity ratio greater than 1 indicates that value of the deal's assets exceeds the value of its liabilities.

- Excess Spread and Reserve Fund

-

- Excess spread is the positive difference between interest earned on student loan assets and interest paid on bond liabilities. Cash flows from the loan collateral that exceed those paid to noteholders may be deposited into a trust's reserve fund. Deals can be structured such that, at issuance, a reserve fund is equal to a certain percentage of assets or a certain dollar amount. Reserve funds may be drawn down in the case of a shortfall or replenished in the case of a surplus. If a structure's parity ratio falls below 1, excess spread may accumulate to build towards a parity ratio greater than 1.

- Tranching

-

- Subordination, or tranching, establishes a priority of payments for holders of different tranches of the deal and provides credit enhancement for more senior tranches. Generally, in cases where there is an interest shortfall during a payment period, senior notes are paid interest before subordinate notes. After interest is paid, remaining cash goes towards principal payments, which are also paid to the notes in order of seniority. This senior-subordinate relationship between tranches is often depicted visually with senior bonds shown above junior bonds, as in Exhibits 9 and 10, above.

- Bond Insurance

-

- Issuers can purchase bond insurance from financial guarantors like Ambac Financial Group and MBIA. This insurance guarantees principal and interest payments to noteholders if the issuer were to default. An insurance wrap typically allows a bond to obtain a higher credit rating than it otherwise would. Over the past several months, monoline insurers have experienced their own financial difficulties, for example, in 2008 both Ambac and MBIA lost their AAA designations from Standard and Poor's and Moody's.30 Following these events, market participants have generally viewed monoline insurance as less valuable and have analyzed issuer credit quality more closely to gauge default risk.

Student Loan Auction-Rate Securities (SLARS)

As shown by the example structures we describe above, student loan asset-backed securities may be fixed-rate or variable-rate, and some variable-rate SLABS are student loan auction-rate securities (SLARS). Interest rates for SLARS are determined through a periodic auction process. When current holders of auction-rate securities (ARS) wish to sell a greater amount than potential buyers wish to purchase, an auction fails, as described in detail in NERA's previous publication, "Auction-Rate Securities: Bidder's Remorse?" After auction failure, the interest rate is reset to a specified maximum rate that is defined in the security's offering documents.

In February 2008, the ARS market as a whole experienced a wave of auction failures. Many issuers responded by restructuring or refinancing their ARS; for example, of an estimated $165 billion of municipal ARS, about $100 billion have been restructured or refunded.31 For SLARS, the failures beginning in February 2008 have generally continued to the present, but the amount of student loan ARS outstanding remains at approximately the same level, about $85 billion. While some investors in securities experiencing failed auctions have continued to hold, other investors have traded municipal SLARS at or near par. Market observers have spoken of several factors leading to these failed auctions including concerns about the health of the monoline bond insurers, concerns about the liquidity of ARS, and the lack of broker-dealer auction participation in the form of supporting bids.

Maximum Auction Rates

While some ARS have simple maximum rates, such as a fixed rate of 12%, maximum rate formulas for student-loan backed ARS are generally more complex. They are typically a function of a fixed rate and one or more variable rates such as LIBOR, Treasury, or commercial paper rates. Formulas commonly use a multiple of a variable rate (e.g., 175% of the 91-day Treasury bill rate, capped at 14%) or a variable rate plus a spread (e.g., one-month LIBOR plus 50 basis points, capped at 18%). This multiple or spread may be based on the bond's credit rating with rating downgrades triggering higher multiples or spreads. The maximum rate definition sometimes also includes a feature limiting the average rate a security pays out over a period to the average of a benchmark rate (sometimes plus a spread) over a given period. For example, the maximum rate formula for a student loan ARS could be something like the minimum of (1) 150% of LIBOR if the bond is AAA-rated and 200% of LIBOR for a lower credit rating, (2) the average commercial paper rate over the last year, and (3) 12%.

Student loan ARS structures experiencing failed auctions pay ARS noteholders maximum auction rates and receive cash flows from student loan collateral. These cash flows include Special Allowance payments on FFELP loans tied to commercial paper and Treasury rates, as discussed above. When SLARS have maximum rates tied to other variable rates, such as LIBOR, noteholders may be harmed if the different rates diverge. In other words, the liabilities of the structures (the auction-rate bonds) may be tied to one interest rate while the assets of the structures (the student loan collateral) are tied to another rate. Thus, SLARS investors may be exposed to basis risk, the risk that the relationship between two interest rates will adversely change.

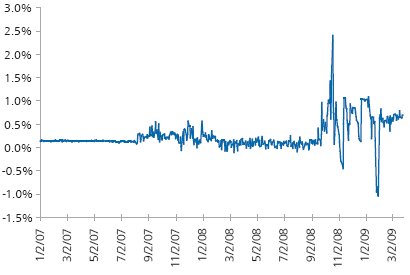

This basis risk is also present in non-auction-rate SLABS structures which own FFELP loans, as many of these structures issued bond liabilities with rates tied to LIBOR. In fact, since August 2007, the spread of LIBOR over commercial paper rates has experienced increased volatility, as seen below in Exhibit 11.32

Exhibit 11. Spread Between Three-Month USD LIBOR And 90-Day AA Financial Commercial Paper

Sources: Federal Reserve, British Bankers Association. When data are not published for a particular day, we rely on the most recent data available.

Fitch recently conducted a review of student loan ABS trusts focusing on basis risk exposure, after which it placed 132 subordinate tranches on rating watch negative. The rating agency said that while it had "included basis risk stresses in its analysis of the transactions at the time the initial rating was assigned, recent rate movements ha[d] far surpassed the historical volatility upon which the prior assumptions were based."33

Available Funds Caps

The interest paid on a student-loan backed auction rate security may also be subject to an available funds cap. In some instances, this feature may introduce default risk into a structure, even with no defaults on the underlying collateral. An available funds cap attempts to keep a structure solvent in the event of prolonged auction failure or other unforeseen financial stresses. Available funds caps may be either rate-based or dollar-based. Dollar-based caps limit the amount of interest that the SLARS can pay out based on the dollar amount of net interest from the underlying collateral. Rate-based caps similarly limit interest rates paid on SLARS to the net loan rate, i.e., the rate that loan holders receive less applicable fees, such as servicing costs.

Rate-based caps may introduce default risk into a structure as follows: If a structure's parity ratio is less than 1, this means the trust's liabilities (amount of outstanding notes) are greater than its assets (amount outstanding of student loans). In this case, when one applies the net loan rate to the liabilities, the dollar amount of interest owed on the liabilities will exceed that earned on the assets. There will be interest shortfalls because of this difference resulting from applying the same percentage to a larger base.

Rate-based available funds caps have affected some SLARS in this way. In 2009, Fitch conducted a review of SLABS with auction-rate exposure, after which it downgraded 84 bonds. Most of the downgrades occurred in undercollateralized trusts with an available funds cap: "In most cases, the imbalance between the assets and liabilities created a mismatch between the earnings received on the assets and the interest expense paid on the bonds."34

Conclusion

An appreciation of recent events in the primary and secondary markets for student loans requires understanding student loans, the structure and cash flows of student loan asset-backed securities, and the nature of these securities' risks to investors. The market for student loan asset-backed securities has been influenced by changes in short-term interest rates, credit market conditions, and higher education policy, among other factors. While some auction-rate securities have been refinanced by issuers, this has generally not been the case for ARS backed by student loans. In addition to pending litigation, claimants continue to file new lawsuits and arbitration claims involving auction-rate securities and asset-backed securities, including those backed by student loans.

Recent student loan legislation has provided primary and secondary market liquidity for student loans and will likely do so going forward. We will track these developments with interest in their impact on student loan asset-backed securities and the markets for these structured products.

Footnotes

* Stephanie Lee is a Senior Consultant and Max Egan is an Analyst with NERA Economic Consulting. We thank John Montgomery for extensive discussion and comments. We also thank Chi Mac, Chudozie Okongwu, Steven Olley, and Arun Sen for helpful comments, and Kara Hargadon and Nolan Scaperotti for excellent research assistance.

1. NERA's May 2008 publication, "Auction-Rate Securities: Bidder's Remorse?" explained the auction process in detail, discussed these auction failures, and described the auction-rate securities market.

2. The College Board, Trends in Student Aid, 2008.

3. ibid.

4. The Federal Health Education Assistance Loan Program (HEAL) operated from 1978 until 30 September 1998, when new HEAL loans were discontinued. Under this program, graduate students in medicine, dentistry, optometry, pharmacy, and other health fields could obtain federally guaranteed loans. Existing HEAL loans continue to be guaranteed by the Department of Health and Human Services.

5. Private lenders may charge borrowers less than the maximum rate allowed by law if they so wish. Many private lenders offer discounts and rebates to borrowers if borrowers meet certain criteria, such as making all payments on time for two years. The Department of Education also offers discounts on Direct Loans, for example, for borrowers who have payments auto-debited from their bank accounts.

6. The proportion of federal loans made under the FDLP program decreased over the 1998 – 2008 period, as shown in Exhibit 1. While this chart does not reflect the most recent data, we note that this trend reversed for the 2008-2009 year due to several factors including changing profitability of originating FFELP loans. SLM Corporation 2008 10-K, p. 7.

7. "Report on Marketing Practices in the Federal Family Education Loan Program," US Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, 14 June 2007.

8. Sam Dillon, "Drilling Down on the Budget – Student Loans," New York Times, 27 February 2009.

9. Under the Federal Perkins Loan Program, schools act as lenders using funds provided by the federal government.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs, GI Bill website, accessed at http://www.gibill.va.gov/.

11. "Secondary Market Activities of the Student Loan Marketing Association," US General Accounting Office, 18 May 1984.

12. Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, Quarterly Financial Report, 31 December 2008 and 31 December 2007.

13. First Marblehead 2008 10-K.

14. Interestingly, this year, the Department of Education released separate draft default rates for the FFEL Program and Direct Loan Program. For fiscal 2007, the FDLP had a default rate of 5.3% (4.7% for 2006 and 4.1% for 2005) while the FFELP had a 2007 default rate of 7.3% (5.3% for 2006 and 4.7% for 2005). Department of Education, "FY 2007 Draft Student Loan Cohort Default Rates," 26 March 2009.

15. While loan holders' default insurance is less than 100%, insurance is for 100% of principal and accrued interest in certain cases of loan discharge, such as borrower death or disability.

16. In the past, some loans had a higher guarantee percentage if their servicer had "exceptional performer" status, as defined by the US Department of Education. Exceptional performer status was eliminated in 2007. 20 U.S.C. § 1071 et seq. (as amended by Pub. L. No. 110-84 § 302, 121 Stat. 796 (2007)).

17. Reinsurance is 100% for discharged loans. A guarantee agency's default rate is the percentage of its loans' borrowers who enter repayment in a fiscal year and default or meet other specified conditions by the end of the next fiscal year.

18. Payment of special allowance on FFEL loans, 34 C.F.R. § 682.302 (2008).

19. SIFMA, US ABS Outstanding, available at http://www.sifma.org/uploadedFiles/Research/Statistics/SIFMA_USABSOutstanding.pdf.

20. FinAid, Lender Layoffs and Loan Program Suspensions, http://www.finaid.org/loans/lenderlayoffs.phtml accessed 11 May 2009.

21. State of Michigan, Department of Treasury Notice, 15 April 2008; Statement from MEFA's Executive Director, 28 July 2008.

22. Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, "PHEAA Temporarily Suspends its Student Lending Activity," 27 February 2008.

23. FinAid, Lender Layoffs and Loan Program Suspensions, http://www.finaid.org/loans/lenderlayoffs.phtml accessed 11 May 2009; the College Board, Trends in Student Aid, 2008.

24. SLM Corporation 2008 10-K, p. 89; SLM Corporation 2007 10-K, p. 93; First Marblehead 2008 10-K, p. 11; First Marblehead, "First Marblehead Announces Third Quarter Fiscal 2009 results."

25. US Department of Education, "US Department of Education Completes Work on Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Conduit and Announces Loan Purchase and Participation Programs for 2009-2010 Loans," 16 January 2009; US Department of Education, "US Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings Takes Steps to Ensure Students Continue to Have Uninterrupted Access to Federal Student Aid," 8 November 2008; "Education: Tuition Ammunition: a Happy Lesson on Lending," The Wall Street Journal, 6 January 2009; US Department of Education, "Fiscal Year 2010 Budget Summary," 7 May 2009.

26. To be eligible as TALF collateral, SLABS must be issued on 1 January 2009 or later, be rated AAA by two major rating agencies, and not be rated below the highest investment grade category by any major rating agency. SLABS with either federal or private loan collateral are eligible.

27. Federal Reserve press release, "Federal Reserve announces the creation of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF)," 25 November 2008; Federal Reserve Bank of New York, TALF Operation Announcements 19 March 2009 and 5 May 2009; Federal Reserve Bank of New York. "Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility: Frequently Asked Questions."

28. Connecticut Student Loan Foundation, website accessed at http://www.cslf.com/aboutus.htm.

29. These tranches are labeled A-3 and B-2 because the Connecticut Student Loan Foundation had previously issued A-1, A-2, and B tranches in 2007.

30. The term "monoline insurer" refers to an insurance company that writes financial guarantee contracts.

31. Jeffrey Rosenberg, et al, "Debt Research – Cross Product Research," Bank of America, 13 February 2008; Andrew Ackerman, Jack Herman, and Patrick Temple-West, "Beyond the ARS Collapse; Lawyers Eye Taxable Build America Bonds," The Bond Buyer, 4 March 2009.

32. Due to dislocations in the commercial paper market, the Department of Education adjusted its Special Allowance rates for the fourth quarter of 2008 to rely on rates posted by the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). The Federal Reserve established this Facility in October 2008 to enhance the liquidity of the commercial paper market. This Department of Education fourth quarter 2008 adjustment decreased the spread between commercial paper and LIBOR applicable to holders of FFELP loans, thus, eliminating some of the basis risk we discuss here. The Department of Education made no such adjustment for the first quarter of 2009.

33. Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Places 132 Subordinate U.S. FFELP Student Loan ABS Tranches on Rating Watch Negative," 5 May 2009.

34. Business Wire, "Correction - Fitch Announces U.S. Student Loan ABS Auction Rate Review Results," 30 April 2009.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.