Coffee is never far from my mind. Particularly at this time of year, when we are treated to seasonal delights such as the gingerbread latte, the peppermint mocha, and even the chestnut praline frappucino®. However, one coffee that I had five years ago proved particularly notable despite being a humble, not in any way festive, regular latte.

December 2015 is when I was first drawn in to the world of patents. That included reading a patent for the first time. On the train. On the way to an interview for my current job as a trainee patent attorney for Marks & Clerk LLP.

The train journey from Glasgow to Manchester for the interview included a change at Carlisle, which seemed the perfect time at which to get breakfast. As remains my go to choice even today, I picked up a latte and a blueberry muffin.

Time-wise, 2015 seems not so distant, but culturally it seems a long way off where we are now. For me, 2019 was the year of the on-the-go reusable cup, and there is no denying that 2020 has been the year of sipping coffee from your favourite mug at home. But 2015 was arguably the height of our frivolous use of disposable cups without thought to the environmental consequences. So, as was expected at the time, my latte at Carlisle train station came in a single use vessel.

On the train out of Carlisle I noticed that the lid of the disposable cup had a patent number stamped into the plastic. When presented with such a glaring opportunity to educate myself a little more on the profession I was considering entering, it seemed the prudent thing to do to look up the patent and have a read. And what a read it was! Baffling. Mystifying. Why was it so verbose? Why was it so repetitive? What had I let myself in for?

Thankfully (whether due to that coffee or not) I have now had five years working in the world of patents to learn the answers to those questions, and I hope to be able to shed some light on those questions in this brief guide to the anatomy of a patent.

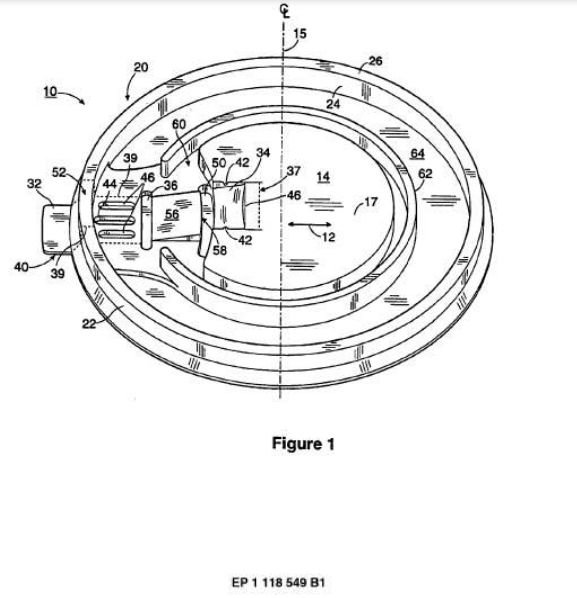

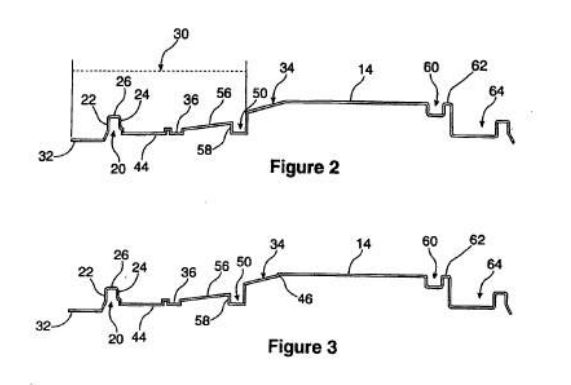

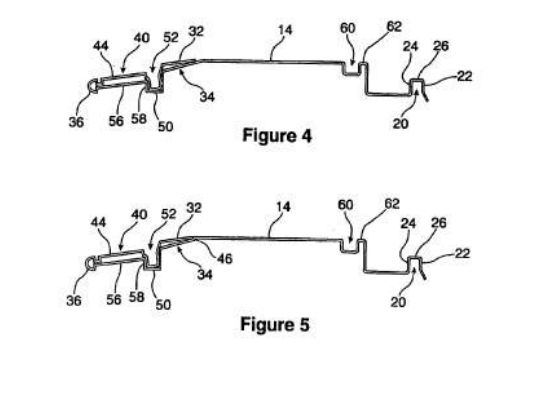

As any patent attorney will tell you, no good description of a thing is complete without accompanying figures to assist in the explanation, therefore in this case we will take European patent EP 1 118 549 B1 for a 'Disposable Cup Lid' as an example. I cannot say whether this is the same patent that I came across that day back in 2015, but it is sufficiently similar to provide a nice segue.

If you click on the patent number provided above, this will direct you to the 'espacenet' patent database where you can study the patent in more detail if you are so inclined. The 'espacenet' database is an invaluable resource where most published patents from around the world can be viewed.

Although this is a European patent that we are looking at here, patents from the majority of countries contain similar content presented in a similar way.

The front page of a published patent is where we find all of the bibliographic information relating to the patent including the patent number, the patent office that has issued the patent, the title of the patent, and the date of grant of the patent. It also states the proprietor of the patent and the inventor. The proprietor and the inventor are often not the same. In general the inventor has the right to a patent for their invention. However, the rights may instead belong to another party, either due to the inventor being an employee of the other party or the inventor having assigned their rights to the other party.

Moving past the front page and delving into the patent specification you will find a text portion and a portion made up of figures. In Europe the figures are presented at the back of the specification, with the text preceding. In other jurisdictions, notably the US, the figures are presented first with the text following. Either way, the figures and text are grouped and separated rather than having the figures interspersed throughout the text as you might find with a journal paper or an article.

Unconventionally, we will now jump to the end of the text portion of the patent specification. This is the claims, and is titled as such so that it can easily be identified. We have B-lined for this section of the patent specification because the claims are the most important part of any patent. It is the claims that legally define the monopoly right afforded to the proprietor by the patent. The claims state the invention in sufficient detail that all of the features essential to making the invention new and inventive over what has gone before are included, but in as broad terms as possible so as to maximize the protection provided by the patent. The format of the claims is a series of numbered statements that define features of the invention. Some of the statements refer to preceding statements. This is a form of short hand to include all of the features of the referred to statement in the subsequent statement. Statements that do not make any reference to other statements are known as independent claims, and are the broadest definition of the invention. Statements that do refer to other statements are known as dependent claims.

In Europe, all granted patents are published with the claims in English, German and French. This is a quirk of European patents. These are the three official languages of the European Patent Office, and it is only natural that the most important part of the specification be provided in all three official languages.

Now that the important part is out of the way, we can look to the rest of the text portion of the specification – the description. This is where things can appear to be verbose and repetitive. But not without reason.

Background: First of all there is provided background information on the invention. This includes information on the general area of technology, the current 'state of the art', and problems associated with the conventional technology. In a granted European patent such as our example, you would expect the background to also include some reference to other patents.

These are the documents that have been identified as most relevant to the invention during the patent application process.

Summary: Following the introduction, there is a summary of the patented invention. This section includes substantially the same text as the claims but written in sentences rather than numbered statements. These sentences, corresponding to the claims, are interspersed with other sentences describing preferred and optional features of the invention, and benefits provided by the features of the invention.

Brief Description of the Figures: Next is a brief description of the figures. This merely provides a brief introduction to what is shown in each of the figures.

Detailed Description: Finally, there is a detailed description that sets out specific examples of the invention with reference to the figures. In some jurisdictions this section of the specification may be referred to as a best mode of implementation or similar. The language used in the claims and in the summary section appears again in the detailed description, however it includes further specifics of the examples depicted in the figures. As can be gleamed from the name of this section, these examples are set out in great detail. Where there are multiple different examples of the invention, the same or similar language will be used to describe common features between each example.

As you may have gathered, there is much emphasis on using consistent language throughout the patent specification, and on describing as many possible options as can be envisaged in as much detail as is available. The reason for this comes down to the process that a patent application must go through before it is granted.

In the majority of cases, the claims of a patent application will require some reformulating in order to ensure that they describe an invention that is new and inventive before the patent is allowed to grant.

The amendments made to the claims during this reformulation must come from the information that is provided in the patent application at the time that it is filed. New features cannot be introduced, and new combinations of features cannot be cherry picked from the original examples provided. The use of consistent language and providing as much information as possible in a patent specification allows for greater flexibility when it comes to that process of amending the claims.

Although their seeming verbosity and repetitiveness may result in patent specifications not making the most enthralling read on a long train journey, these are imperative characteristics for a patent to have the best chance of providing the proprietor with useful protection for their invention.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.