This Essential Guide concentrates on the powers, duties and obligations placed upon a director of a private limited company in the UK.

Although there are hundreds of specific duties imposed by legislation in the UK on directors, it was only with the implementation of the relevant provisions of the UK Companies Act 2006 (the "Act"), all of which were in effect from 1 October 2008, that the general duties of directors were put on a statutory basis. Prior to that time, directors' general duties were built up by common law and were developed by the courts in a somewhat unsystematic way. This codification has not altered the scope or extent of directors' duties in any material way; it has, however, put them firmly in the spotlight.

The principal statutes covering directors' duties, in addition to the Act (summarised below), are the Insolvency Act 1986 and the Insolvency Act 2000. The legislation then ranges from those statutes which are generally applicable to almost every type of company—taxes, employment, health and safety—through to those which may apply as a result of a company's status or particular field of business activity. These statutes often impose personal liability (including criminal liability) on directors of companies found guilty of offences or non-compliance.

As a result, the codified duties in the Act do not cover all the duties that a director may owe to his/her company. Some of these other duties are set out elsewhere, while others remain uncodified (for example, the duty of confidentiality).

These duties are owed to the company; however, the Act has introduced into statute the common law concept of the derivative claim (a claim made by a shareholder in the name of, and for the benefit of, his company). The Act contains new provisions on derivative claims which may increase the number of such claims being brought.

Further specific areas of concern for directors relate to:

- Insolvency

- Confidentiality

- Listed Companies – companies whose shares are listed and traded on the London Stock Exchange (whether the Main Market or AIM) must adhere to rules imposed by various regulatory authorities such as the London Stock Exchange, the Takeover Panel and the Financial Services Authority.

DIRECTORS' POWERS

The basic premise is that the directors of a company act as a board. When they do so, the company will be bound by their acts, if they are within the scope of the directors' collective authority. Any limits on the board's powers are generally set out in the company's articles of association (see the "Essential guide ... to establishing a business in the United Kingdom" for details). It is important to note that the Act provides that, broadly, the power of the board to bind the company (or to authorise others to do so) is deemed to be free of any restrictions in the company's articles. Therefore, a party to a transaction with the company is not required to enquire whether the transaction is permitted by the company's articles or as to any limitation on the powers of the board of directors to bind the company.

DIRECTORS' DUTIES

Companies Act Duties

1. Duty to act within powers To act within powers, the director has a duty to comply with:

- the company's articles;

- decisions taken in accordance with the company's articles; and

- decisions taken by the shareholders where they are decisions of the company.

2. Duty to promote the success of the company When considering how to act in the way which would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, a director should have regard to the following factors as set out in the Act:

- the likely consequences of any decision in the long term;

- the interests of the company's employees;

- the need to foster the company's business relationships with suppliers, customers and others;

- the impact of the company's operations on the community and the environment;

- the desirability of the company maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct; and

- the need to act fairly as between members of the company.

Notwithstanding this list of factors (which is nonexhaustive), the director should remember that his key concern should not be to have satisfied each and every item, but rather to consider properly how best to execute his judgment as a director in good faith, assessing properly the wider implications any action he takes may have.

3. Duty to exercise independent judgment

Directors must exercise their judgment independently. This does not mean that the director cannot take and rely on advice, but he must exercise his own judgment in deciding whether to follow such advice. In addition, a director cannot do anything to fetter the future exercise of his discretion unless acting in accordance with an agreement duly entered into by the company, or in a way authorised by the company's articles.

4. Duty to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence

At a minimum, the director owes a duty to the company to exercise the same standard of care, skill and diligence that would be exercised by any reasonably diligent person who has the same knowledge, skill and experience that might reasonably be expected of someone carrying out the same functions as that director. This objective assessment is supplemented by a subjective level of assessment of conduct: if a director has specialist knowledge, that knowledge will also be attributed to the "reasonably diligent person". In addition, the duty of skill and care has the following aspects:

(i) Diligence and attention to the business. A director must diligently attend to the affairs of the company. Directors are not bound to do so continuously, but must be sufficiently in touch with events to ensure that any matter which may have a material impact on the financial state, business or assets of the company, will come to their attention promptly;

(ii) Reliance on others. A director can rely on the other officers of the company (provided he has made proper enquiry of them). A director can also delegate power to others where it is reasonable to do so (e.g. accountants). However, directors should keep themselves informed of the delegate's activities and are obliged to intervene in circumstances which would put an honest and reasonable man on enquiry as to potential wrongdoing;

(iii) Liability for the acts of the company. In the absence of a specific statutory duty a director is not personally liable for civil wrongs committed by the company, unless he ordered (or procured) that the acts were done.

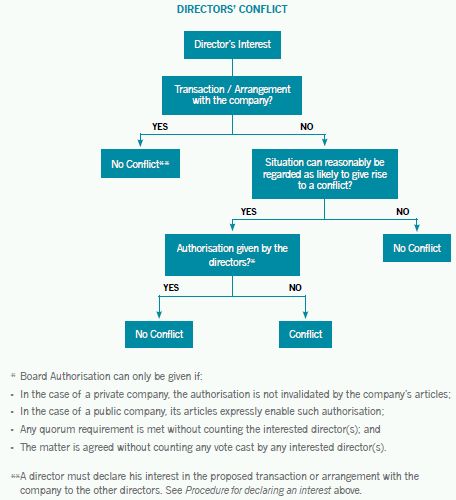

5. Duty to avoid conflicts of interest

Directors have a duty to avoid any situation in which they have, or can have, a direct or indirect personal interest that conflicts, or could conflict, with the interests of the company (other than those arising from a transaction or arrangement with the company). This applies regardless of whether or not the company could take advantage of it. More details on this issue are set out below.

6. Duty not to accept benefits from third parties

Directors cannot accept a benefit from a third party which is offered to them because they are a director, or in connection with doing (or not doing) anything as a director. Because this relates to third parties, any benefits from the company are excluded. It is possible under the company's articles to ensure that directors may legitimately receive third party benefits up to a certain value, provided that they do not breach the relevant provisions of the Bribery Act 2010 (see Dechert OnPoint – Update on UK Bribery Act 2010 for details). Board guidance on the circumstances in which acceptance of benefits cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict would be sensible.

7. Duty to declare interest in proposed transaction or arrangement with the company

Directors have a duty to declare to the board the nature and extent of any interest, direct and indirect, in any proposed transaction or arrangement with the company. It is important to note that the director need not be a party to the transaction for this duty to apply; if the director has an interest in someone else so transacting, he must notify the board.

However, no declaration is necessary if:

- the director is not aware of his interest or of the transaction (but this is subject to a reasonableness test);

- the interest cannot reasonably be seen as giving rise to a conflict of interest or if the other directors are already aware of it; or

- the director is the only director of the company.

The director owes his duties to the company, and only the company will be able to enforce them, but shareholders may be able to bring a derivative action on the company's behalf.

Procedure for declaring an interest

The declaration must be made before the company enters into the transaction or arrangement and may be made:

- at a meeting of the directors; or

- by notice in writing to the other directors.

If this declaration of interest proves to be, or becomes, inaccurate or incomplete, a further declaration must be made.

Duty of confidentiality

A director owes a duty of confidentiality. This duty overlaps with the duties to promote the success of the company and to avoid conflicts of interest.

Directors will clearly obtain a significant amount of company information. They are entitled to receive notice of and to attend board meetings and they can also inspect and take copies of the records of the company (including minutes of meetings). However, the extent to which a director has unrestricted access to company information of which he has no first-hand knowledge is not clear cut. A director has a common law right to examine the company's books of account in order to be able to discharge his duties, and he probably has a statutory right to examine the company's books of account for the purposes of complying with the Act.

The duty of confidentiality is such that, even where the director is appointed by a shareholder, he must not, without the authority of the company, disclose to that shareholder any confidential information relating to the company which has been gained by him as a director of that company. This duty of confidentiality owed by a director to a company is greater than any duty he owes to his appointing shareholder to report information to that shareholder. This also applies where there is a conflict between the interests of the company and those of the appointor. To avoid difficulties, it is good practice for the board of a company to agree in advance with any shareholder what categories of information can be passed to that shareholder by its nominated director. This is often provided for in a shareholders' agreement and it may be appropriate to require confidentiality undertakings to be obtained from recipients.

Duties in respect of conflicts

Arrangements with the company itself

Directors are not under a duty to avoid interests in transactions or arrangements with the company. However, he must disclose an interest in a transaction or arrangement that the company is proposing to enter into, or that it has already entered into (whether that interest is direct or indirect). Once that interest is declared, no authorisation is required. See "Procedure for Declaring an Interest" above. The director has a duty to keep the board updated of any changes in his interest.

Third party arrangements

In a case not involving a transaction or arrangement with the company, a director must (unless the board has given prior authorisation) avoid a situation in which he has, or can have, a direct or indirect interest or duty that conflicts or possibly may conflict with the interests of the company.

In the case of a public company, the articles must contain express permission before the board can authorise conflicts. Private companies incorporated before 1 October 2008 must have passed a shareholder resolution to allow the board to authorise conflicts. The directors of private companies incorporated on or after 1 October 2008 can authorise conflicts unless the articles prevent this.

It may also be necessary to consider the interests of those connected to the director (broadly, his spouse, partner, children and step-children) as this may constitute an indirect interest.

INSOLVENCY

When a company finds itself in financial difficulties (either approaching insolvency or actually insolvent), directors must, in certain circumstances, consider or act in the interests of creditors of the company. While this does not mean that the directors should ignore other considerations, the interests of creditors will assume prime importance. For example, directors cannot settle a claim against a third party without taking into account the interests of creditors.

Where a company is, or may be, in financial difficulties, a director (or, in some cases, a shadow director) may have additional concerns under the insolvency legislation. The three main areas of concern are wrongful trading, fraudulent trading and disqualification.

CONSEQUENCES

Statutory duties (save for the duty to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence) are enforceable in the same was as any other fiduciary duties: breach can give rise to a number of potential remedies, including paying damages/compensation to the company and accounting to the company for any profit made. The duty to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence is not a fiduciary duty and, as a result, the remedy for breach is damages.

Disqualification

Under the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986 a court may make a disqualification order, such that a person shall not, without leave of the court, be a director of a company or in any way, whether directly or indirectly, be concerned or take part in the promotion, formation or management of a company for a specified period beginning with the date of the order.

The minimum period of a disqualification order is two years and the maximum is 15 years.

Indemnities and insurance

The Act renders void any indemnity given by a company to a director (including any other UK company in the same group) against liability which he might incur in respect of his negligence, default, breach of duty, or breach of trust in relation to the company. This also applies to any arrangement exempting the director from such liability. However, this does not prevent the company from taking out (and paying the premiums for) insurance against such liability. Therefore it is common for companies to take out such insurance for the benefit of their directors.

There are certain exceptions to the prohibition on a company protecting its directors from liability under the Act:

- Companies are permitted to indemnify directors against certain liabilities owed to third parties.

- Companies are permitted to indemnify directors of a company that is a trustee of an occupational pension scheme against liability incurred in connection with the company's activities as trustee of the scheme.

- Companies can fund directors' legal costs incurred in defending claims against them at the time such costs are incurred (rather than waiting for the proceedings to conclude). However, in most cases, the director must repay the company if the proceedings are not ultimately concluded in his favour.

CONCLUSION

While some of the information set out in this Essential Guide may appear daunting to a prospective director, the key points for a director to bear in mind are to act with reasonable diligence, adopt the highest standards of propriety in conduct and where (and just as importantly when) appropriate, seek and act upon competent professional advice. Provided these tests are met, a director can feel reasonably confident about the role he is being asked to undertake.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.