Explore how private equity could unlock new growth potential and broaden your exposure to a changing economic spectrum.

Over the past few decades, structural forces have significantly reshaped the roles of public and private equity in the economy. The rise of the intangible economy has allowed many asset-light businesses to meet their capital needs through the rapidly expanding private equity industry, enabling them to stay private for much longer. As a result, the private equity opportunity set has grown substantially, while public equity has seen a sharp decline in the number of listed companies across major economies.

This shift has altered the nature of newly listed companies. Academic research reveals that today's IPOs involve companies that are, on average, significantly older and larger than those of 20 years ago. For public market investors, this means gaining access to companies much later in their growth journey—if at all.1

The implications for portfolio construction are clear. With fewer listed companies, the public markets no longer fully represent the economic spectrum required for diversification. The shift toward private equity has transformed the investment landscape, leaving public equity investors grappling with a narrower and less representative market.

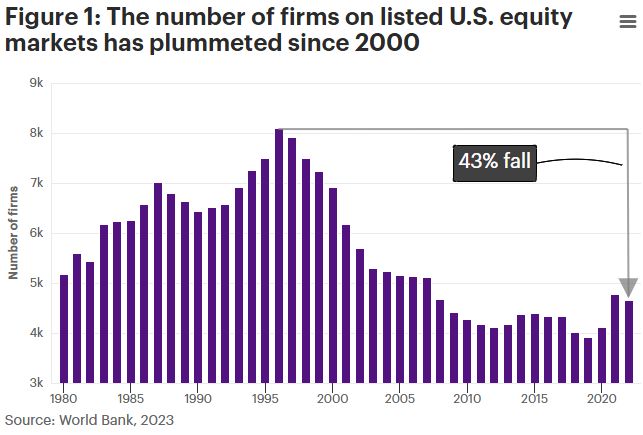

The number of public companies in the U.S. has plummeted from a peak of over 8,000 in the late 1990s to just above 4,000 in recent years (Figure 1). The pace of public listings has slowed to a crawl: between 1980 and 2000, an average of 310 companies went public annually in the U.S., whereas from 2001 to 2011, that number dropped to just 992.

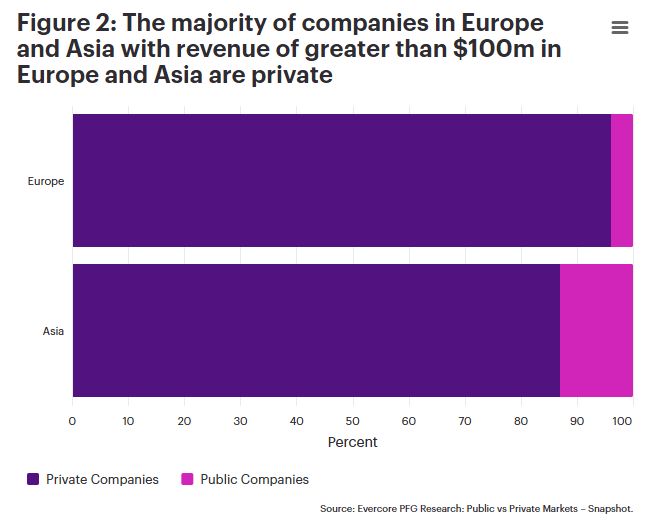

This isn't just a U.S. phenomenon. Similar declines have been observed in other major economies, with large companies in Europe and Asia now overwhelmingly dominated by those in the private space (Figure 2).

Why companies are avoiding public markets

A confluence of structural and economic factors has made public markets less attractive to many businesses. Today's knowledge-based business models are often asset-light, relying on outsourcing for manufacturing, computing, and administrative needs. This lowers the barriers to entry but also makes these companies vulnerable to competition and imitators—risks magnified by the transparency required in public markets.

At the same time, corporate investment has increasingly shifted toward intangible assets, such as R&D and intellectual property, which now outpaces tangible asset investment in economies like the U.S. and U.K.3 Accounting standards treat these expenditures as expenses, depressing earnings and making such companies less appealing to public market investors.

Adding to this the perception that public markets prioritize short-term results, the substantial costs of IPOs (roughly 5% in the U.S.4), and rising compliance burdens, it's therefore no surprise that some businesses are opting to stay private—or to reverse course by delisting.

Private equity: The rising alternative

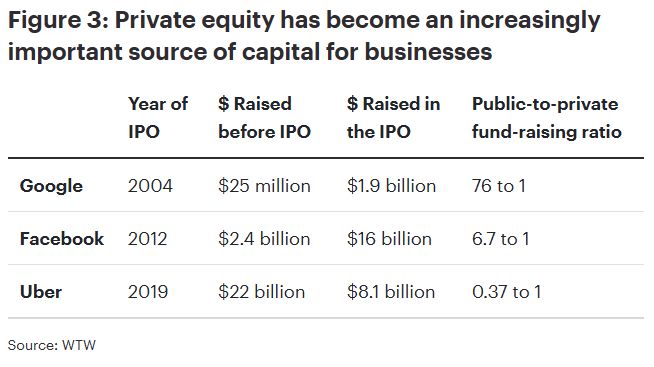

Even as public markets become less desirable, businesses still need capital. Increasingly, they're finding it in the private equity space, which has grown more than sixfold since the start of the 21st century to over $3 trillion5 by 2018 (Figure 3). This explosive growth has positioned private equity as a true rival to public markets in providing business funding.

It is important to note that private equity is a higher risk asset class and as such, investments can negatively perform resulting in loss of capital.

Investment implications: Missing out on growth

For public market investors, the shift has significant consequences. Academic research6 reveals that newly listed companies today are, on average, much larger and older than those of two decades ago. By the time these companies hit the public market, much of their high-growth phase is behind them—if they make it to public markets at all. Notably, private equity typically has longer holding periods (5-7+ years) and is far less liquid than public equities. Investors should be comfortable with this characteristic before seeking exposure.

Meanwhile, public markets are increasingly dominated by mature, cash-rich giants (think Big Tech) that generate substantial revenue but could soon face natural limits to growth. From a diversification perspective, the public equity market is becoming narrower, offering fewer opportunities to access the full business lifecycle.

Embracing private equity: The case for broadening equity exposure

As private equity continues to expand at the expense of public equity, investors reliant solely on public markets may find themselves missing out on a significant portion of the investment opportunity set. Including private equity in investment portfolios could offer access to otherwise unattainable companies with distinct risk profiles—providing diversification and exposure to earlier-stage growth.

If you have any questions or would like to know more, please contact us using the details below.

Footnotes

1. "Where have all the IPOs gone?," Xiaohui Gao, Jay R. Ritter and Zhongyan Zhu, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 2013. Return to article undo

2. "Where have all the IPOs gone?," Xiaohui Gao, Jay R. Ritter and Zhongyan Zhu, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 2013. Return to article undo

3. "Capitalism without capital – the rise of the intangible economy," Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake, 2018. Return to article undo

4. "Where have all the IPOs gone?," Xiaohui Gao, Jay R. Ritter and Zhongyan Zhu, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 2013. Return to article undo

5. "Capital formation: the evolving role of public and private markets," Sviatoslav Rosov, CFA Institute, 2018. Return to article undo

6. "Is the U.S. Public Corporation in trouble?," Kahle, Kathleen M., and René M. Stulz, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2017. Return to article undo

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.