- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

Competition authorities in Europe and the United Kingdom are

increasingly focusing in on labor markets in their enforcement

activities. This is part of a wider, global trend in enforcement.

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission moved to ban

employee non-competes (see our April 2024 Advisory). Even though the law

itself has not changed in Europe and the United Kingdom,

competition authorities have increased their enforcement focus on

employment practices. Moreover, the current UK government proposed

introducing legislation to limit non-competes to three months, and

we will see whether the new UK government will pick up this

proposal after the upcoming election.

Employers and human resources (HR) professionals should therefore

be aware of developments in the rapidly changing competition

enforcement landscape.

What Are the Agencies Interested In?

The idea that collusion on labor can amount to anticompetitive conduct is not new, but historic enforcement cases are sparse. This is changing. New guidance from the European Commission and the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) indicates the three most likely forms of conduct which will trigger their interest are:

1. No-poaching agreements: Where two or more firms agree not to approach or hire one another's employees, either absolutely or without consent.

2. Wage-fixing agreements: Where two or more firms aim to fix employees' pay or equivalent benefits.

3. Information sharing: Where competitors share

commercially sensitive information relevant to

employment, such as standard employment terms or wage levels,

either directly or indirectly. This could also extend to

benchmarking exercises where wage or

other confidential information is exchanged.

Importantly, you don't need a contract or formal

agreement to be caught: For competition law purposes,

an "agreement" does not need to be a written contract. It

can be a verbal exchange, a "gentlemen's agreement,"

or just an understanding. The concept captures very soft

understandings and that is a core area of potential exposure,

particularly in industries where HR professionals from competing

firms meet in special fora or trade bodies. With respect to

information exchanges, simply receiving and giving information can

be enough.

What Are the Key European Union and UK Enforcement Cases?

In January 2024, the CMA expanded the scope of its investigation

of the UK fragrances sector to include "unlawful

coordination ... involving reciprocal arrangements relating to the

hiring or recruitment of certain staff," likely a form of

no-poach agreement. Similarly, the CMA is also currently

considering employment-related issues in parallel investigations

into the sports and non-sports broadcasting sectors. Here, the

CMA's suspicions concern potential coordination regarding both

direct employees and freelance employees from whom services are

purchased, though precise details of the alleged breach have not

been made public.

At the same time, the European Commission conducted dawn raids in

November 2023 to expand the scope of their investigations into the

online food delivery sector to include

potentially (in their view) anticompetitive no-poaching agreements

between competitors.

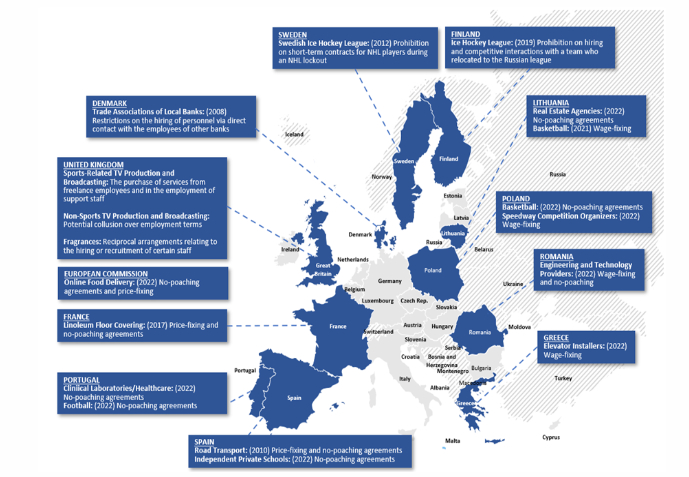

The following visual shows countries that have actively pursued such cases. This means that any company with a European footprint needs to have in place proper procedures to avoid creating antitrust risk.

Figure 1 - European competition cases relating to labor markets.

In parallel, the UK government released a policy paper

indicating plans to limit non-compete clauses in employment

contracts to a maximum term of three months. This will require a

change in legislation, and, given the UK general election, one

needs to see if the new government takes up this initiative. This

may fall by the wayside, given other pressing demands on the new

government's schedule, but if implemented, such a change may

well be the death knell of non-competes in the UK because it would

rarely be worth the time and expense of going to court to enforce a

restriction of only three months' duration.

The ongoing focus on non-competes and employment terms in the

context of competition was reemphasized in a detailed report on the

topic by the CMA's Microeconomics Unit in January 2024, and the

topic was flagged as an area of ongoing focus in the CMA's

2023-2024 Annual Plan.

Transparency, Benchmarking, and Trade Associations

Anticompetitive collusion between competitors is not limited to

actively agreeing to fix certain employment terms, such as wages or

notice periods. A simple exchange of competitively sensitive

information (e.g., sharing insufficiently aggregated salary data on

a one-time basis) could breach competition law. At the same time,

employers are also under increasing pressure to disclose employment

data, such as salaries, in pursuit of pay transparency. Fulfilling

all statutory duties, therefore, requires that employers walk a

tightrope, fulfilling employment law disclosure requirements

without breaching competition restrictions.

Past examples of competition authorities treating information

exchanges as anticompetitive even if they are not part of a wider

cartel include reciprocal (or unilateral) exchanges of information

without further agreements or understanding as to conduct. Hence,

there is a significant risk that competition authorities will apply

this more actively in the employment sphere.

Moreover, information exchange via independent third parties, such

as a trade association, does not necessarily shield an employer

from antitrust risk if the information is not sufficiently historic

or aggregated. For example, in the Polish basketball case listed

above (see Figure 1), members of the Polish Basketball League

agreed to each withhold pay from players on account of the season

ending early during the COVID-19 pandemic. A system of information

exchange between the teams via a third party, the league itself,

enabled this coordination. Similarly, this could occur via wage

benchmarking efforts through a trade association if data is

insufficiently historic, aggregated, or genericized.

What Does This Mean for Busy HR Professionals?

Protecting against anticompetitive behavior, and subsequent

enforcement actions, presents a complex challenge — all the

more so for HR teams already acting in a highly regulated field.

The risks will be even greater where a company is potentially

dominant in its field and attracts more scrutiny from competition

authorities. The first step in any compliance program is to conduct

up-to-date training and education of staff on competition

restrictions and use internal reporting tools to sensitize HR

professionals to the potential of antitrust risk and familiarize

them with the concepts of competition law. This should ideally be

backed up by internal policies or guidance given by employers to

relevant managers and HR professionals to demonstrate that the

employer is on top of this area and is not encouraging collusion or

unlawful information exchanges.

As an ongoing measure, particular care should be paid when

conducting disclosure or transparency initiatives, where a degree

of information release is required, and to industry initiatives,

such as through trade associations or other third parties. HR

professionals should proactively seek input from their internal or

external lawyers from an early stage when being presented with or

developing such initiatives.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.