January 2022 - The Turkish Board fined five major supermarket chains and one of their common suppliers for hub-and-spoke cartel.

Background

In the months following the emergence of Covid-19 in Turkey, excessive price increases were observed in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), which triggered the submission of complaints to the Turkish Competition Authority. In the context of the pandemic, the Competition Board also took the liberty of initiating investigations ex officio in order to elaborate whether undertakings in the FMCG sector restricted competition. The Board's recent landmark decision concerns an investigation against 29 undertakings and an association of undertakings for the examination of the pricing behaviour of chain markets, and undertakings operating at the manufacturer and wholesaler level that are suppliers to the FMCG sector. As a result of the investigation, the Board imposed a record fine on the supermarkets A101, BIM, Carrefoursa, Migros and Sok as well as their common supplier, Savola, a cooking oil producer, for violating competition law through a hub-and-spoke cartel.

Within the scope of the investigation, the Board conducted comprehensive analyses in which it requested certain information from the investigated parties, approximately 130 undertakings as well as third parties such as the research companies Nielsen and Ipsos, and official bodies. In addition, the Board took an interim measure obligating the parties to the investigation to disclose each week the price increases in food and cleaning products to the Board.

Subsequent to a series of written defences, additional information requests and an exhaustive oral hearing that started at 10:30 a.m. and finished at 2:30 a.m. the next day, the final decision1 was made that some of the undertakings subject to the investigation had indeed engaged in anticompetitive behaviour.

The decision is extremely significant as it provides a comprehensive understanding of the definition of hub-and-spoke cartels under Turkish competition law, as explained further below.

Board's assessments

Within the decision, the Board provided separate assessments related to the nature of the infringement conducted by and between the supermarkets; A101, BIM, Carrefoursa, Migros and Sok. Furthermore, the Board analysed the role of the common supplier Savola in the establishment of cartel between the supermarkets as the hub. Moreover, the Board also considered the supplier Savola's resale price maintenance practice within the scope of its investigation. In other words, the Board's assessment shed light on its approach regarding three different practices under the same decision: (i) anticompetitive information exchange, (ii) hub-and-spoke cartel, and (iii) resale price maintenance.

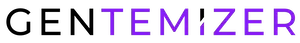

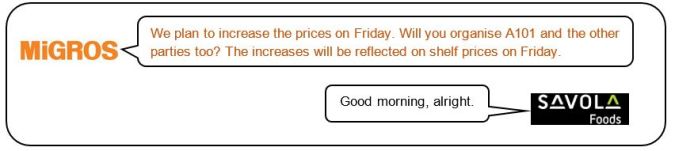

To better demonstrate the evidences that led to the hub-and-spoke cartel, we exemplify parts of the WhatsApp communications below:

In terms of the first prong of its assessment, the Board indicated that A101, BIM, Carrefoursa, Migros and Sok -through Savola- have coordinated prices and price switches (as they say, "organized the market"). The said supermarkets, again by using Savola, exchanged competitively sensitive information such as the future prices, price increase dates, periodic activities and campaigns. The Board also determined that the chain markets had interfered with each other's and other local chain markets' sales prices to increase prices to the same level through the agency of Savola. The Board further understood that the supermarkets even imposed sanctions such as dramatic regional price decreases that could not be met by the local chain markets or the issuance of return invoices to the suppliers in order to constantly seek compliance with the price collusion of competitors. Before reaching its conclusion, the Board evaluated not only evidence of contact/information exchange, but also price studies for the undertakings in the market which demonstrated coordinated and parallel sales prices. In this regard, the Board has defined this practice as "a price-fixing cartel that exhibits hub-and-spoke characteristics", and which is therefore a "hardcore violation".

In this regard, the Board's following assessments are significant to understand what to expect in future decisions:

- Intermediates that facilitate the implementation of a cartel should be held equally responsible for the violation.

- Anti-competitive information exchange through intermediaries (e.g. common suppliers) should be treated as equal to cases where the information is directly exchanged between competitors.

- Even though hub-and-spoke cartels exhibit seemingly vertical characteristics, they are essentially horizontal agreements in nature.

The Board further assessed that, in a normally functioning market, retailers are expected to avoid any direct or indirect contact that has the object or effect of disclosing their market behaviour to competitors. However, in light of the evidence examined during the investigation, the Board came to the conclusion that, the supermarkets, knowing the risk of disclosure of their pricing information to their competitors, deliberately shared the relevant information with Savola, using it as a hub. Correspondingly, Savola communicated to the competitors in the market with regard to the pricing strategy, enabling the cartel.

Moreover, the Board indicated that Savola indeed had interest in ensuring the coordination of the shelf prices, price transitions, and campaigns of the supermarkets and therefore, had the motivation to influence market conditions with the information that it obtained. Given that Savola directly benefitted from price increases in the market, it regularly organised price transitions in the market. Accordingly, the Board ruled that Savola acted consciously and willingly to ensure and maintain price collusion in the market and intensively provided the necessary information flow.

As a result, the Board treated Savola no differently from the supermarkets in terms of categorising its role and responsibility in the hub-and-spoke cartel.

The Board did not stop there while imposing sanctions on Savola. Due to Savola's role as a "supplier" and the evidence demonstrating interference with the resale prices of its resellers, the Board also imposed an administrative monetary fine on Savola based on its resale price maintenance actions.

Competition Board's previous approach towards hub-and-spoke practices

Under Turkish competition law there is no specific provision regulating hub-and-spoke arrangements. Before the case at hand, the Competition Board did not impose any penalties directly for hub-and-spoke arrangements, yet it explicitly evaluated hub-and-spoke cartels in its Tyre2 and Aral3 decisions. Accordingly, the Board's assessment sets a precedent and is key to analysing and determining hub-and-spoke arrangements. In a nutshell, information exchange between competitors though a common supplier or retailer is considered as a hub-and-spoke arrangement. There are two types of hub-and-spoke information exchange: (i) a common distributor will act as the hub and mediate information exchange between suppliers; and (ii) a common supplier will act as a hub to facilitate information exchange between retailers.

In its Aral decision, the Board assessed whether there was an agreement or a concerted practice by way of a hub-and-spoke arrangement with the intention of (vertical) price fixing. In this case, the retailers expressed their complaints regarding (low) prices offered by their competitors to Aral4 and requested Aral's interference to increase prices.

In its Tyre decision, the Board could not determine the effects of the information exchange through retailers, associations, and research companies. Consequently, indicating that (i) there is no written agreement or evidence to suggest that the object of the alleged conduct aimed to restrict competition, and (ii) distributors exchanged information indirectly and some information was disclosed outside of the control of competitors in the upstream market, the Board decided not to initiate a full-fledged investigation.

We believe that it would not be wrong to express that in the previous cases, the Board found it difficult to establish the causality between the vertical and horizontal components of hub-and-spoke cartels. Therefore, in practice, it interpreted some hub-and-spoke practices as resale price maintenance or as other vertical price-fixing agreements, due to the lack of necessary proof.5 However, through adequate evidence and a thorough analysis, the Board has rendered its first ever decision concluding the presence of a hub-and-spoke cartel.

What is new?

The decision carries weight in identifying the standard of proof for violations of competition using hub-and-spoke practices. The e-mail messages, WhatsApp correspondences and screenshots reveal that, through common suppliers, there was constant information exchange on future-oriented shelf prices and price switching dates, etc., between the market chains. Further, there are numerous communications that make no effort to hide collective price fixing. The Board did not rely solely on communication evidence and also analysed the actual daily tag prices. The analysis also confirms synchronised price movements among market participants. If one of the retailers deviated from the prices the players agreed upon, their immediate reaction (lowering prices again) suggests that there is also a monitoring mechanism as well as a kind of punishment mechanism, because it is understood that retailers issue supplementary sales invoices for rate differences. Accordingly, it can be concluded that the Board came to its decision using both the written and computational evidence as well as the continuous supervision and disciplining aspects that can be inferred from the correspondences.

In hub-and-spoke cartels, hubs and spokes are equally liable for the infringement. To that end, the Board's approach towards the practices of the oil producer Savola deserves particular focus. First and foremost, it can be reasonably expected that Savola also benefits from the retailers' price increases, as this would simply mean more money for Savola. Additionally, the evidence makes it clear that the chain markets (retailers, i.e. spokes) disclosed their future price strategies to Savola which indicated that the acquired price information will be shared with other retailers. Some also specifically requested Savola to disclose the information with other players with a view to affect their market behaviour. In response, Savola assured them that the other retailers will also mark-up prices. Hence, Savola played an essential role in the creation of the hub-and-spoke cartel and thus should be held equally liable as the retailers.

Conclusion

This decision marks the first decision in Turkey where the scope of hub-and-spoke arrangements and the standard of proof are set out with comprehensive examples. It is undeniable that this decision sheds light on future assessments in Turkey for hub-and-spoke cartels. Prior to this case, it could be said that the Board did not consider anticompetitive information exchange sufficient for the formation of a "cartel" in some cases. This was a hot topic for some time, as it was also a grey area in the legal framework and Turkish legislation did not provide a clear definition of what a "hub-and-spoke cartel" is in practice. In this decision, the Board defined the conduct of A101, BIM, Carrefoursa, Migros and Sok as constituting a cartel that demonstrates hub and spoke characteristics very clearly and defined the acts that led to this conclusion in detail. An important factor that led to the Board's rather strict approach in this case is the evidence of direct communication between the competitors and their common supplier, Savola. Evidence of such direct communication was lacking in previous cases, where the evidence was based on only indirect communication. Accordingly, an administrative monetary fine of approximately EUR 176 million in total was imposed on the aforementioned five undertakings as a result of their behaviour with respect to the coordination of prices.

As for Savola, as the common supplier and as the hub in this context-the Board found the company equally and jointly liable based on the grounds that it contributed to the coordination between the retailers even though it was fully aware that this information was or could be the fuel to restrict competition. The Board fined Savola approximately EUR 1.48 million for its cartel behaviour. Additionally, the Board imposed an administrative monetary fine of approx. EUR 740,000 on Savola based on the grounds that it violated Article 4 of Law No. 4054 by determining the resale prices of undertakings operating at the retail level. On a final note, no administrative monetary fine was imposed on the other parties to the investigation, given that there was no concrete evidence of a violation of Law No. 4054.

Footnotes

1. The

Board's Chain Markets decision, dated 28.10.2021 and numbered

21-53/747-360.

2. The Board's

Tyre decision, dated 16.12.2015 and numbered 15-44/731-266.

3. The Board's

Aral decision, dated 07.11.2016 and numbered 16-37/628-279.

4. Aral was an

Istanbul-based firm that had distribution rights for the leading

video game, console, and accessories companies.

5.

DAF/COMP/WD(2019)107, Hub-and-spoke arrangements - Note by

Turkey.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.