- within Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

- in European Union

- within Transport and Insurance topic(s)

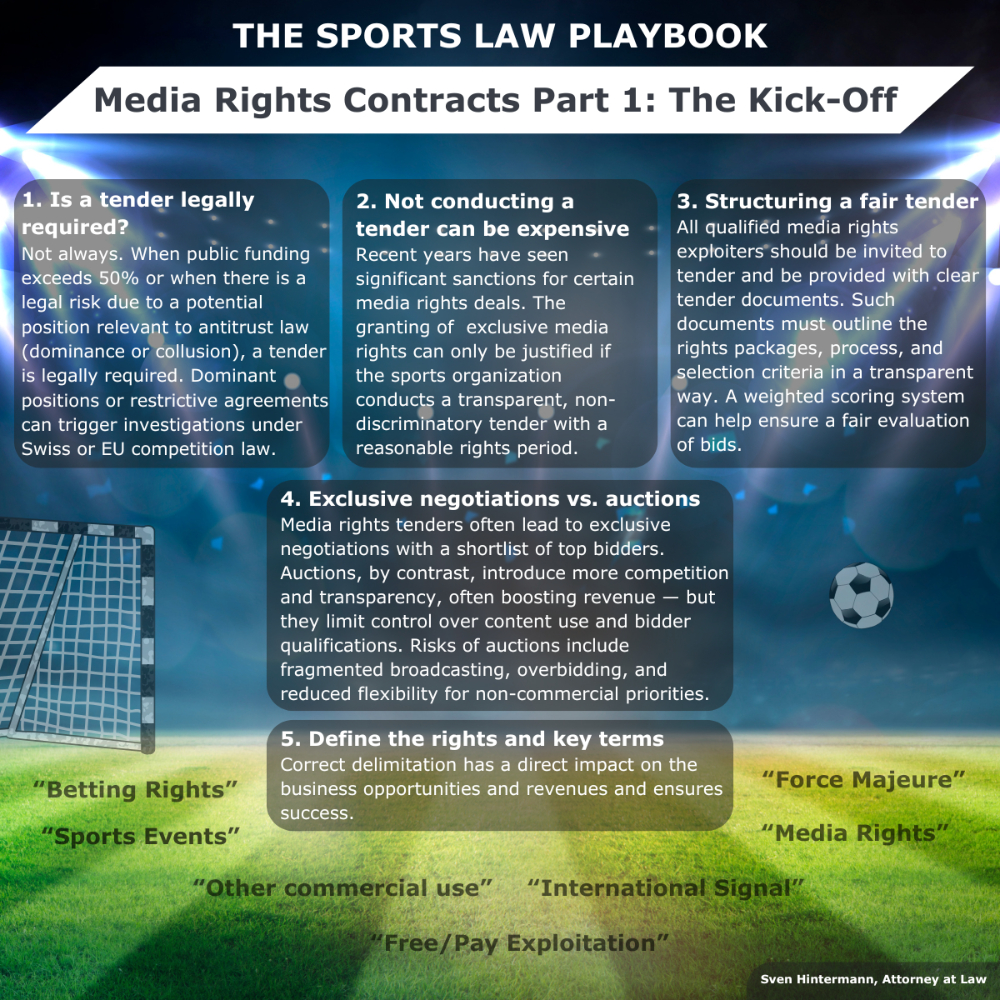

This mini-series, part of our sports law blog, looks at negotiating media rights contracts in the sports business. If a rights holder wants to market their media rights, they need to set the right course from the outset, even before they actually start contract negotiations with potential contractual partners. This not only promises ultimately successful marketing from an economic perspective, but also protects against legal risks that, if implemented incorrectly, can lead to years of investigations and disputes that ultimately harm the sport in multiple ways. Part 1 addresses the process of how media rights are awarded and offers practical tips on how to successfully enter into negotiations for media rights agreements.

Listen to this article:

Negotiating Media Rights Agreements in Sports Part

1: The Kick-Off - VISCHER | Podcast on Spotify

s a tender for media rights even legally necessary?

When it comes to the awarding of media rights, we repeatedly see sports organizations asking themselves whether they need to put the rights out to tender again for a new rights period. This is because there are often exclusive first negotiation clauses from the expiring contract period or established partnerships with media rights exploiters (e.g., as host broadcasters and/or marketers of a sporting event), which, from the perspective of the sports organization that owns the media rights, make it impossible or completely unreasonable or inefficient to award the rights to another party rather than to its long-standing media rights partner.

In the case of sports organizations as holders of media rights, we generally assume that they are clubs (or sports associations) within the meaning of Art. 60 ff. of the Swiss Civil Code. However, the requirements described here apply regardless of the legal form. This means that they may also apply, for example, to a stock corporation outsourced or commissioned by the sports association to market media rights.

At first glance, an obligation to put media rights out to tender may arise from two sources:

- Sports promotion and the staging of sporting events are often supported by public organizations. This raises the question of whether the awarding of media rights is subject to public procurement law. The short answer is that purely private organizations without dominant state funding or without sovereign tasks are not subject to procurement law in Switzerland. In other words, this means that if 1) a sports organization does not perform any sovereign tasks (which is hardly ever the case) and 2) the public sector finances a sports organization (or, for example, an individual sporting event) or provides comprehensive deficit guarantees, thereby subsidizing the sports organization (or sporting event) by less than 50 percent of the total costs (see Art. 4 para. 4(b) of the Intercantonal Agreement on Public Procurement [IVöB]), Swiss procurement law does not require a tender procedure for the award of media rights in connection with the sporting event.

- However, marketing activities by sports organizations are regularly subject to Swiss and, under certain circumstances, European antitrust law. On the one hand, sports organizations often have a dominant position (within the meaning of Art. 7 of the Swiss Cartel Act [KG] or Art. 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [TFEU]). On the other hand, a competition agreement may exist if an agreement restricts competition in the relevant market (see Art. 4 para. 1 KG or Art. 101 TFEU). In order to assess whether a relevant market dominance or a competition agreement relevant from an antitrust perspective exists, the legal relationships between the sports organization concerned and any third parties (e.g., participating clubs or subordinate associations) with regard to the media rights to be marketed must first be examined. Such legal relationships vary depending on the sport and level within the hierarchical structure of sport organizations (regional, national, international). In the case of competition agreements, it must then be examined whether they are permissible on the basis of sufficient justification. In the case of market dominance, it must be examined whether the sports organization is actually abusing its position (and thereby hindering competition or disadvantaging competitors) and what measures should be taken to prevent such abuse. It must also be noted that the assessment of when conduct constitutes a violation of antitrust law may differ between Swiss and European antitrust law. In particular, when sports organizations are internationally oriented, it is essential to take into account the practice under European antitrust law.

The above-mentioned principles do not automatically give rise to an obligation to tender media rights. The circumstances of each individual case must be examined. Taking into account the specific characteristics of a sport, the position of the sports organization in the ecosystem, and the rights and obligations of the various stakeholders and actors involved, there may be an obligation to tender. However, this is not always the case. Practice shows, however, that competition agreements and/or a dominant market position regularly exist, particularly when exclusive rights are granted (e.g., to individual buyers in individual territories). In most cases, the granting of such exclusive rights in the event of a possible competition agreement and/or a dominant market position can only be justified if the sports organization in question conducts a transparent and non-discriminatory award procedure and sets the rights period for a reasonable (and not too long) duration (usually two to three years). In case of doubt—i.e., if there are no legally valid reasons against an invitation to tender—we recommend conducting a tender procedure.

Not conducting tender process can be expensive

In recent years, competition authorities in Europe and Switzerland have imposed heavy fines on sports organizations for awarding media rights without an appropriate tender process. For example, the Italian competition authority imposed a total fine of around EUR 66 million on the Serie A soccer league and several media partners for dividing the TV rights for 2015–2018 among themselves in a "mutually agreed solution" instead of putting them out to tender fairly. The Competition Commission (WEKO) has also taken action in Switzerland: Swisscom and its pay television subsidiary Teleclub were fined CHF 71.8 million in 2016 for abusing their dominant position in the marketing of soccer and ice hockey games. Both the Swiss Federal Administrative Court and the Federal Supreme Court later upheld these fines. In 2020, a sanction of CHF 30 million was imposed on UPC (now Sunrise) because the cable network operator had refused to share its exclusive live broadcasts of the ice hockey league with competitors for many years (this sanction was also largely confirmed by the Swiss Federal Administrative Court).

Such cases show that it can be extremely expensive for sports organizers to award audiovisual media rights without a transparent tender process. However, as explained above, a tender is not required in all circumstances (e.g., when marketing non-exclusive rights, etc.).

What must a sports organization consider when inviting tenders for rights?

If a sports organization decides to issue a call for tenders, even if this was not strictly required by law, the following points must be observed when conducting the call for tenders:

- A general call for tenders can be made public via the sports organization's media (e.g., its website). However, since there is often no legal obligation to make a public tender, we recommend that the sports organization inform the public via a press release on its website that it will invite suitable media rights exploiters to participate in the tender from a specific date. This information should ideally be provided more than one month before the start of the tender process or the provision of the tender documents. As a rule, such a procedure is also reasonable because not all exploiters are in a position to exploit the relevant media rights (e.g., if they do not have the necessary capacity or expertise to market or produce certain sporting events). In this press release, however, a sports organization may also invite users who are not scheduled to be invited to contact the sports organization if they are interested in participating in the tender. Depending on the position of the sports organization and the addressees of the tender (if, for example, the European market is also affected), a more comprehensive public tender or an invitation procedure may be necessary.

- The sports organization should at least directly invite all suitable users to submit tenders by official letter and enclose the relevant tender documents or detailed information. Normally, the suitable users (which may be TV broadcasters as well as marketing and/or production agencies) are well known in the market. The (public) press release may also attract other users to the award procedure. The more likely an obligation to issue an invitation to tender exists, the more care a sports organization must take to invite all users participating in the market.

- For reasons of transparency, the tender documents should

provide information about the exact procedure of the award process

and the composition of the rights packages put out to tender. They

should also specify in detail the award criteria and any

documentation requirements for bidders (qualifications, technical

capabilities, creditworthiness, etc.) and refer to applicable

sports regulations. For the award criteria, the sports organization

may, for example, also provide for a scoring system that weights

various criteria on a percentage basis (e.g., 30% price, 30%

broadcast reach and guarantees, 30% production quality, and 10%

promotion).

Initiating exclusive individual contract negotiations and awarding contracts

Award procedures that begin with a call for tenders are often designed in such a way that a few of the best bids are selected from among all those submitted, and these potential contractual partners are then invited to exclusive individual contract negotiations on the same or different rights (depending on the composition of the rights packages). Because negotiations of media rights agreements can be lengthy and complex, a media rights holder is usually well advised to limit the detailed negotiations to packages of identical rights with a small number of potential contractual partners (per rights package). This procedure should also be specified in the tender documents (see above). The best offer (per rights package tendered) is then awarded the contract for a specific rights period.

Awarding rights through auctions instead of lengthy individual negotiations?

In addition to individual negotiations following tenders for media rights, sports organizations sometimes also award media rights through auctions. In this process, interested media companies can submit their bids for the respective packages (which contain minimum prices as well as other award criteria) in parallel or in rounds within a predefined period. Depending on the auction design, these can be sealed bids (all bidders submit their bids once without knowing the others) or open bidding rounds (all bidders see the current highest bids and can outbid each other). At the end, the highest bid usually wins the package.

An auction process ensures strong competition, drives up prices and thus revenues, and is considered more transparent – all bidders have equal opportunities, as the highest bid is determined openly. However, there is a risk of fragmentation of the broadcasts if different providers purchase individual packages – consumers would then often need multiple subscriptions to view different content from the same sport. In addition, bidding wars can lead to excessive bids: if a winner calculates too optimistically, financial problems and, in the worst case, a re-award may ensue. Last but not least, in such a process, sports organizations lose control over certain factors that may be important to them from a non economic perspective (e.g., the technical/editorial expertise of a media company for certain sports, the negotiation of reservation rights, broadcasting obligations via certain channels of the media company to promote the sport as widely as possible, the handling of archive rights, and so on), which they can only define to a limited extent in award criteria within the framework of an auction.

The awarding of media rights and the contractual relationship surrounding them is often complex and cannot always be integrated into a relatively rigid auction process, the implementation of which can involve a great deal of effort for many sports organizations using suitable technical systems. Subsequent changes or the introduction of additional requirements at extremely short notice within the framework of an auction process that is already very tight in terms of time can lead to lengthy legal disputes, which recently even led to a new auction in the case of the German Football League and the streaming platform DAZN.

Setting the decisive course: Essential definitions of rights and terms

In order to determine the scope of the rights granted in media law agreements, it is crucial to define the relevant terms. This is by no means simply a legal technicality, nor is it something that should only be drafted or reviewed by legal advisors. Correct delimitation has a direct impact on the business opportunities and revenues of a sports organization, which is why the definitions of essential terms should be established at the outset of contract negotiations. In practice, sports organizations pay particular attention to the following terms and sometimes consider the following points:

"Media Rights":

Depending on the user, it must first be considered whether the sports organization grants the rights exclusively (e.g., for a specific territory) and whether the user may sublicense them or otherwise transfer its rights, and this must be specified in the scope of rights. These are rights that may include the recording or production, transmission or broadcasting, recording, communication, and other audio/visual distribution of the sporting events covered by the contract. The sports organization usually grants these rights

- for the duration of the contract (whereby the use of images produced in-house is also agreed in some cases beyond the term of the contract),

- only in specific or all possible forms of use (such as live, delayed, in the form of complete broadcasts, for reporting or for compiling highlight clips), and

- for specific or all forms of media and transmission options (e.g., radio/TV, Internet, wireless/mobile communication systems and via terrestrial waves, cable, telephone, satellite, cable, and other digital or analog media known at the time of signing the contract or invented during the term of the contract).

With regard to the purpose of use, it must also be considered whether certain types of exploitation and purposes are to be excluded from the granting of rights. This applies, for example, to the following areas:

- In addition to all transmission offers (e.g., free/pay television), also making the content available at public or private events or other public/closed facilities (e.g., in airplanes, trains, hospitals, hotels, cinemas, military bases, or on ships).

- streaming rights in connection with sports betting,

- use for further commercial exploitation (e.g., licensing to advertisers),

- use for film purposes (e.g., for sequences in documentaries), or

- use for further sporting or technological exploitation (sports

organizations or their players are increasingly using the produced

(international) signal to collect and analyze data on sporting

performances — the sports organization then wants to

regularly prevent this right from also being granted to the

exploiter for further marketing within the scope of the rights

granted, but instead wants to market this itself or obtain the data

centrally).

"(International) Signal":

This is the image produced during a sporting event (usually by a host broadcaster) that is delivered to all users in the different territories for use. If the international signal already contains elements other than just images of the competition, such as statistics overlays and other graphics or commentary in one or more languages, this should also be specified in the description of the international signal (sports regulations may even impose additional requirements on the international signal, which the sports organization should also take into account when defining the international signal). In some cases, the parties also negotiate the possibility of producing an additional signal that allows the sports organization to integrate virtual advertising, augmented reality elements, or 360-degree feeds for a user within the legally permissible framework (or for certain territories).

"Sports Event":

Here, it is not only important to ensure that the parties describe the event or competition or competition series/league in such a way that there can be no doubt as to which sports events the user is granted media rights for, but it is also crucial to specify the exact time at which a sports event begins and ends (e.g., before or after the awards ceremony). Depending on this, there may be significantly more or fewer interesting images for a user, and depending on this, a sports organization may divide individual parts of a sporting event among suitable users. In addition, larger sporting events often feature many interesting side events that a sports organization may also be able and willing to market (separately).

"Streaming rights in connection with sports betting":

Foreign users and agencies regularly want to secure rights in connection with sports betting. This mainly concerns the rights to stream sporting events in sports betting shops or via mobile applications or websites, whereby a sports organization normally attempts to contractually grant such streaming rights only on condition that such streaming is in lower resolution, after a bet has been placed, and only for registered bettors. This exploitation of media rights may not be relevant in Switzerland due to the restrictive provisions of the Money Gaming Act, but Swiss sports organizations repeatedly grant such rights to foreign sports betting providers for their territories. However, because these streaming rights may interfere with the exclusive use of other exploiters in certain territories, a clear contractual distinction must be made in each case (and also be coordinated back-to-back with other exploiters).

"Further Commercial Use":

Because exploiters of media rights accumulate an archive of many images and highlights in their territories over time, they have another potential source of income by sublicensing excerpts to advertisers for integration into their advertising. From the perspective of the sports organization, it is advisable to consider whether it wishes to allow such further commercial use or not — and also whether this use should be possible beyond the end of the contract and, if so, until when. In any case, the parties should include this possibility of use in the definition of terms so that they can regulate it later in the contract as necessary and as negotiated.

"Free/Pay Exploitation":

In particular, if the sports organization wishes to oblige the exploiter to comply with certain broadcasting obligations on (advertising-financed) free-to-air television, it makes sense to distinguish between free exploitation and pay exploitation. Free exploitation is when users of a program can watch the sporting event without a subscription or other fee (where "free" does not, of course, mean the infrastructure, equipment, or reception via a telecommunications network in general), either on TV or via other free platforms, in order to increase the audience reach in the interest of the sport and its sponsors. In the case of pay exploitation, however, the operator of a platform regularly demands compensation for the reception of a specific channel or platform or, in some cases, for individual sporting events ("pay per view").

"Force Majeure":

In addition to the usual provisions on force majeure events in Swiss contracts, consideration must always be given to which events fall under force majeure and which do not – and for which events what consequences should be provided for (e.g., from what "threshold," such as the number of events or the duration of events, the exploiter is granted reduction or compensation rights – so that both parties can better plan for possible natural events). This is particularly important in the case of sporting events that take place outdoors (and not in a stadium). If, for example, the parties include "severe weather" as a blanket term in the force majeure clause and this automatically releases the performing parties from their contractual obligations, there is no meaningful mechanism for dealing with bad weather. In exposed sports, such a mechanism should rather be regulated in detail elsewhere in the contract and excluded from the term force majeure. We will come back to this later.

In the next blog post in this mini-series on the negotiation of media law contracts, we will discuss the granting and transfer of rights between the parties, as well as the rights and obligations relating to the production and supply of the international signal.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.