INTRODUCTION

In Vietnam's bustling investment environment, companies are scrambling for liquidity to ramp up their operations. However, successful businesses need deep pockets if they wish to scale in proportion to the rapidly growing domestic market. Eager to soak up capital to boost their commercial success, local companies have started reaching for foreign funding to augment their expansion plans. This cash can come in multiple forms. It could be provided by private equity investors, classic financial institutions, or modern credit facilities. In the context of a developing economy and propelled by the global economic crisis induced by the Covid-19 pandemic, an increasing share of funds also originates from venture capital.

What unites all these sources of new money invested into a business's growth - and, ultimately, its revenue - is the investors' desire to obtain the highest achievable security for their (re)payment claims against the borrower. Viable security can be obtained from third-party guarantors. However, collateral more commonly consists of mortgages, pledges, and other security instruments between borrower and lender. The parties typically document these through a security agreement. This may or may not form part of the underlying credit facility and sets out the conditions for foreclosure and exploitation of the security asset. It allows the lender to satisfy his claims for repayment through the liquidation of a provided collateral asset (such as real estate, shares, or other assets) against a defaulting debtor.

Therefore, the actual commercial value of the lender's secured payment claim against a borrower (or thirdparty guarantor) also depends on evaluating the collateral provided against the loan. This includes the asset's commercialized monetary value, its availability for monetarization, any related transactional costs for recovery, as well as the legal enforceability of the security agreement against the counterparty or any involved third parties.

It is equally important to predict the consequences of debtor bankruptcy and any existing formal, legal, or procedural hurdles for exploiting the collateral. The recovery of claims for repayment might have to be translated into an enforceable, local court judgment, which can be lengthy and expensive.

This document outlines the legal framework for taking out security in Vietnam. It examines the most used contractual structures, security assets, and typical enforceability issues when setting up a credit facility with a Vietnamese borrower. It also provides a highlevel summary of the security vehicles available under Vietnamese law and touches on the most important structures and prevalent legal issues when taking out security in Vietnam.

Any obligation under a contract can be subject to a security interest as long as it is legitimate and supported by a valid security agreement. In Vietnam, secured transactions are widely used in a variety of industries, such as financing activities involving debts or bonds, project partnerships where the performance is guaranteed with a contractual bond, or deposits into an escrow account, which provide security for payment agreed under a joint venture.

Secured obligations may be current obligations, future obligations, or conditional obligations. Future obligations can only be subject to security if they are formed during the term of the individual security, unless otherwise agreed. An obligation may be wholly or partly secured, as agreed or as provided by law. Where there is no such individual agreement or provision in law, the obligation - including the obligation to pay interest, fines, and compensation for any damages - shall be deemed to be wholly secured.

One asset can provide security for several obligations if, at the time the security transaction is established, the value of the property is greater than the total aggregate value of the secured obligations. In this case, the securing party must inform any othersecured parties that the asset is also employed as security for the performance of other obligations. The provision of security must be made in writing.

Conversely, a single obligation may be secured with severalsecurity assets. In case the debtor defaults and, in the absence of any other agreement between the parties about the succession of exploitation, the secured party will select the order of exploitation.

A single obligation may be secured with several security assets. The security agreement between the securing and secured parties sets out the scope and value of each provided security asset for the underlying obligation. Where there is no such agreement, the secured party may use any of the assets to exploit a mature claim at its discretion.

I. IDENTITY OF SECURITY GIVERS

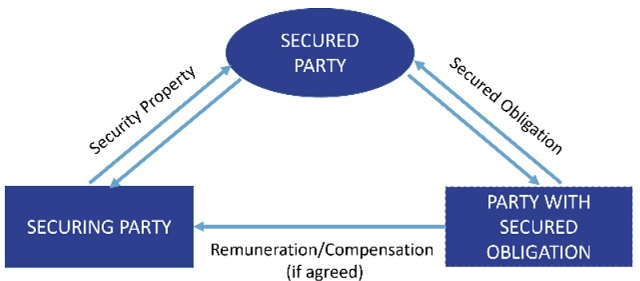

Another critical factor in securing an obligation or other transaction is identifying the security provider, i.e. the securing party. By law, under a security agreement, the securing party may be a pledger, mortgagor, or deliverer of a performance bond, security deposit, or escrow deposit. It can also be the purchaser in a purchase and sale agreement (PSA) in which the ownership right to a property is reserved (retention of title) or a guarantor.

The securing party may provide security for its own or a third party's obligations. However, in any event, the securing party must be the rightful owner of the security asset, except in the case of retention of title or the reservation of ownership rights. Where the property owner and the secured party agree to use the property to secure the obligations of third parties, the regulations on pledges or mortgages apply. The latter's structure can be twofold: Either the asset owner and the secured party enter into a security agreement, or both parties enter into an agreement with the beneficiary of the security agreement.

II. CHALLENGES OF THE SECURITY LAW

Vietnamese law has recognised secured transactions for decades. At the same time, the local legal system has continuously updated its regulations and guidance governing these transactions. As security transactions are generally associated with administrative procedures on statutory or contractual form and enforcement, legislators have focused on simplifying procedures and enforcement. Amongst these developments, Decree 21/2021/ND-CP (Decree 21) forms one of the most recent, that came into force on 15 May 2021. 1 This new regulation is a significant step towards bringing the legislation on security transactions to the next level of maturity.

Footnote

1 Read our update New Decree on Security for Performance of Obligations.

To read the full article click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.