On April 26th every year, we mark World Intellectual Property Day. There seems to be no question about the central role of intellectual property in the modern economy, and it being an important factor in the business strategy of enterprises of all sizes.

The historical origins of the patent system are complex. There is some obscurity concerning the first formal registration of an invention and when the term "patent" was first used in the context of an invention.

There is some evidence that there was something reminiscent of a patent system used by ancient Greek cities (around 500 BCE), but historians recognize that the first formal system of patents originated in Renaissance Italy in 1474, when the Venetian Patent Statute was published in Venice. The Venetian Patent Law, designed to promote technological development and protection for local artisans, is the oldest statutory patent system in Europe, and is considered the oldest patent system in the world. The Venetian Senate granted around 2,000 patents between 1474 and 1788.

One of the first patents to be documented (and some claim that it was in fact the first granted patent right) was the declaration granted in 1421, 600 years ago, by the city of Florence to Filippo Brunelleschi. He was a renowned artist and architect of Renaissance Italy whose main work was in Florence.

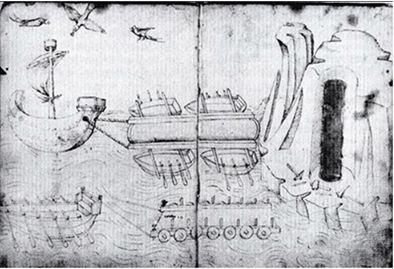

It is highly doubtful whether Brunelleschi intended to appear in the history books as the owner of the first patent. In 1421, Brunelleschi was at the height of the process of building the Florentine Duomo Chapel dedicated to Santa Maria del Fiore. Although he developed a new and ingenious construction method during the construction of the chapel dome that constituted technological innovation, the patent was granted to him for another invention. In fact, it was an invention that came to provide an easy and cheap method for transporting the heavy building materials (especially large marble slabs) that were needed for his construction project. The goods were transported up the Arno River, and the invention that is the subject of Brunelleschi's patent was a type of ship called "Il Badalona". The technical description of the ship does not appear in the text of the patent itself; however, there are several sketches from which one can learn what the ship looked like.

Brunelleschi's 'Il Badalone', taken from the book De

Ingenis by Taccola

Although the Notice by the Lords of Florence is not a "patent" having the structure as we know it today (description, claims, etc.), it contains all the basic principles on which the patent system is based.

The Notice is a decree given by the political and legal authorities of the city of Florence (parallel to the situation today where the patent is granted by the state) recognizing that Filippo Brunelleschi invented a type of ship (a "product" as we would define it today), with distinct uses and benefits: "By which he can easily, at any time, bring in any merchandise and load on the river Arno and on any other river or water, for less money than usual, and with several other benefits to merchants and others..." (Preger, 1946)

That is, the authorities recognized Brunelleschi as an "inventor". They acknowledged that a person's right to the fruit of their imagination and thoughts is not a trivial matter. However, the authorities based their decision on a rather prosaic reason: Brunelleschi was unwilling to make the machine available to the public because he did not want the fruits of his genius (inventive thinking) to be reaped by others without his consent! Luckily, he announced that if he received a suitable reward, he was willing to provide the public with what he had kept as a secret.

In this way, the public would be able to enjoy the benefits of the invention along with the inventor himself. Interestingly, even hundreds of years ago there was an understanding that granting a patent was a way to promote the public good and that it was worth it to pay the required price (namely, to provide a suitable reward to the inventor).

The decree itself prohibited any person "to have, hold or use in any matter" (Preger, 1946) any device intended to carry goods on the water. The prohibition did not only apply to the Arno River (the river crossing the city of Florence and the link between it and the sea) but included:

"any other river, stagnant water, swamp, or water running or existing in the territory of Florence." (Preger, 1946)

It did not refer solely to the transfer of building materials as Brunelleschi's original intention in the construction of the rig, but to the transfer of any kind of goods and products.

Hence, the decree was broad in its definitions and endeavored to capture the spirit of the invention and not limit it to the particular embodiment presented by Brunelleschi, just as it is done today when writing a patent application. There are those who would say that there are buds of greed in this statement, by which the patent owners are trying to expand its boundaries beyond what the inventor has indeed shown.

This broad and significant right that Brunelleschi received was limited in time (it was granted for only 3 years), not very different from the 20-year limit on the lifetime of a contemporary patent.

The decree also explicitly stated that the right to prevent others from producing and using the means of transport did not apply to a device of this type that was known and accepted (familiar and usual) before the date of the decree and was used for the same purposes. Hence, the decree was indeed broad and very comprehensive, but it excluded all those means of transport which were known before Brunelleschi's invention.

The strict decree also stipulated a penalty measure and specified that a vehicle that was found to infringe the patent - would be burned! Nevertheless, the decree explicitly stated that Brunelleschi himself could of course build and use such a vehicle and that he could also allow others to use and build it ("licensing" as it is commonly called today).

The above Italian story underscores the great importance of patents in driving the economy and human development from the beginning of the Renaissance to present day.

*Dr. Mirit Lotan is a patent attorney and a founding partner at Cohn, de-Vries, Stadler & Co.

*Ayelet Shwartz handles media and client relations at Cohn, de-Vries, Stadler & Co.

Prager, Frank D (1946). "Brunelleschi's Patent". Journal of the Patent Office Society. 28.2

Originally posted on LinkedIn (Posted as a post) 26.04.21 https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6792417253506732032

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.