This Article is the first of a series of articles concerning inland waterway transport (hereinafter "IWT") in the EU. This introductory article focuses on the importance of implementing and further developing inland waterways transport in the EU.

IWT, together with road and rail, is one of the three main modes of land transport.

In Europe there are more than 200 inland ports, with more than 37,000 kilometres of waterways1. Half of Europe's population lives close to the coast or to an inland waterway. An important number of European industrial centres can be reached by inland navigation. The Rhine-Danube network alone, with a length of 14 360 km, represents nearly half of the inland waterways of international importance.

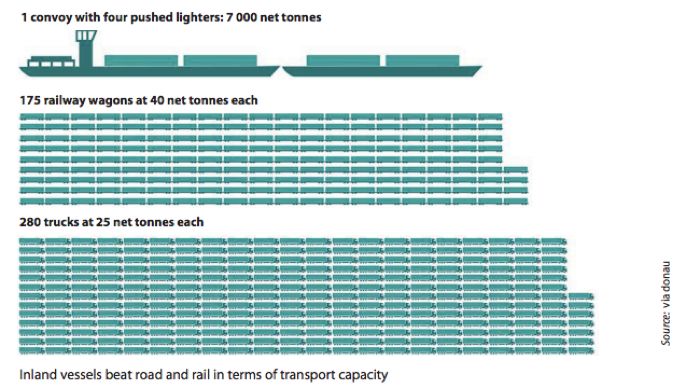

The advantages of inland waterway transport are numerous. IWT is a safe mode of transport with low costs, a lot of spare capacity, no congestion, low noise levels and low energy consumption and a low carbon footprint. Barges and pushed barges can transport more and heavier goods per distance unit (tkm) than any other type of land transport and has a significant role to play in reducing road and rail traffic.

Figure 1 – Source ECA Special Report – Inland Waterway Transport in Europe

The cost of water transport is competitive and the unit cost decreases over long distances. As inland waterway transport is slower than road transport, it is commonly used for goods that do not require fast delivery times, such as metal ores, agricultural products, coke and refined petroleum products, coal and crude petroleum. In the last few years there has also been an increase in container transport, especially in the Rhine basin.

One of the long-term objectives of EU policy is to shift traffic from roads to more environmentally friendly transport modes, such as inland waterway transport, with the idea of helping to reduce pollution and increase transport safety. IWT is, in fact, a sustainable alternative to road, with a smaller carbon footprint and a significant reduction in air pollution. Some of Europe's largest seaports already use inland waterways to tackle increasing congestion and the lack of rail capacity (e.g. Rotterdam, Antwerp and Hamburg).

The European Commission aims to create more favourable conditions for the further development of the IWT, so as to encourage more companies to use this transport mode. In 2006, the European Commission adopted the NAIADES programme. The implementation of NAIADES is supported by the implementation platform PLATINA.

In 2013, the NAIADES programme was updated with the adoption of NAIADES II2. This programme was aimed at promoting inland navigation through: (i) new infrastructure, including filling-in missing links, clearing important bottlenecks and port development; (ii) innovation, including the review of the River Information Services; (iii) market development; (iv) environmental quality, through the reduction of vessel emissions; (v) a skilled workforce and quality jobs; and (vi) integration of IWT into the multimodal logistic chain.

The NAIADES II programme runs until 2020 and is to be implemented by the European Commission, the Member States and the industry itself.

The NAIADES project is supported by the PLATINA project. The PLATINA project has received €8.5 million in funding from the European Commission. This project was implemented in order to provide technical and organizational assistance, by ensuring active participation of key industrial stakeholders, associations and Member States administrations. The PLATINA project is also working on further develop the River Information Services (RIS), which is a modern traffic management system enhancing electronic data transfer between water and shore through in-advance and real-time exchange of information.

The European Commission helps funding and financing IWT development through different programmes, such as the Connecting Europe Facility, Horizon 2020, the European Fund for Strategic Investments and the Cohesion policy.

The European Court of Auditors (hereinafter "ECA") has carried out an analysis of the work done so far by the EU. A Special Report3 shows that the EU tried to implement certain strategies, aimed at eliminating infrastructure bottlenecks that should have been key for the development of inland navigation in Europe. The Report also shows that the goal of shifting traffic from roads and rail to inland waterway transport and improving navigability is yet to be achieved. ECA noted that, between 2001 and 2012, the modal share of inland waterway transport did not increase substantially, remaining at around 6%.

In order to address the difficulties encountered by the Commission in implementing IWT policy, the ECA concluded that, the European Commission and Member States should agree on specific and achievable objectives and precise milestones that should be aimed at eliminating bottlenecks on corridors within the framework of the Connecting Europe Facility. The efforts of the Commission should also take into consideration the TEN-T4 objective of completing the core network by 2030, the availability of funds at EU and Member State levels and the political and environmental considerations in relation to building new (or upgrading existing) inland waterway infrastructures.

The ECA recommends that the Member States should prioritize IWT projects which are on the TEN-T corridors, rivers or river segments that provide the greatest and most immediate benefits for improving inland waterway transport.

However, none of the projects set quantitative targets to be achieved. Today it appears that the only document that has set quantitative targets for inland waterway transport is the "Danube strategy". The Danube Strategy, which obviously has a limited geographical scope, envisages increasing the cargo transport on the river by 20% in 2020 compared to 2010. This goal should be pursued by putting in place both national actions and cross-border co-ordination procedures, in order to respond to the challenges and re-establish optimal and safe navigation conditions.

The work carried until now and that must be carried out in the following years, by both the EU and the Member States is extremely important for an environmentally friendly development of the transport sector in Europe. All the stakeholders should be interested and partake in the development of this transport mode.

In this article we hope we have provided the framework for EU policy on inland waterway transport. In subsequent articles we will look at a number of the legal issues that arise, in particular, concerning the particularities of river transport contracts and the litigation of river transport contracts.

Footnotes

1 See https://www.inlandports.eu/

2 COM (2013) 623 final of 10 September 2013, "Towards quality inland waterway transport Naiades II"

3 European Court of Auditors, Special Report, Inland Waterway Transport in Europe: no significant improvements in modal share and navigability conditions since 2001, Luxembourg, 2015

4 The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) is a European Commission policy directed towards the implementation and development of a Europe-wide network of roads, railway lines, inland waterways, maritime shipping routes, ports, airports and rail-road terminals. The 2013 TEN-T Guidelines were adopted in the form of a Regulation and therefore are binding for the Member States. In order to prioritize waterways within the TEN-T network, the new Connecting Europe Facility and TEN-T guidelines of 2013 established a core and a comprehensive network, which Member States have a legal obligation to complete by 2030 and by 2050 respectively. However, for inland waterways there is no difference between the core and the comprehensive network, which does not help with prioritization within the waterways.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.