Vinay Vaish, Joint Managing Partner, Vaish Associates

Advocates

Email: vinay@vaishlaw.com

+919810200225

Governance Framework of India

"WE, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a SOVEREIGN SOCIALIST SECULAR DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC, and to secure to all its citizens..."

The Republic of India is governed by the Constitution of India, which was adopted by the Constituent Assembly on November 26, 1949 and came into force on January 26, 1950. The Constitution of India seeks to protect the fundamental, political and civil rights of the people. It also embodies the basic governance structure of the country.

The Constitution of India provides for a Parliamentary form of Government, which is federal in structure with certain unitary features.

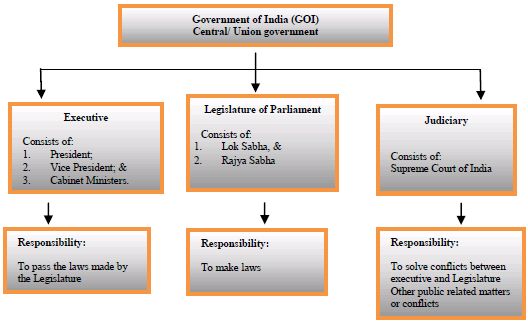

Broadly, the governance structure in India can be depicted as follows:

Transparency, accountability and adherence to the rule of law depends on a systemic arrangement and coherency between the three arms of the state, viz, the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary. The Constitution of India provides for a system of governance based on the above-mentioned three arms within a federal framework with greater powers in the hands of the Union Government or Government of India or the Central Government (also referred to as the "Centre"), which governs the Union of India as a whole.

Legislature

In India, the Parliament is the supreme legislative body. As per Art 79 of the Constitution of India, the Council of Parliament of the Union consists of the President and two Houses, which are known as the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) and the House of People (Lok Sabha). The President has the power to summon either House of the Parliament or to dissolve the Lok Sabha. Each House has to meet within six months of its previous sitting. A joint sitting of two Houses can be held in certain cases.

The cardinal functions of the Legislature include overseeing of administration, passing of budget, ventilation of public grievances and discussing various subjects like development plans, international relations and national policies. The Parliament is also vested with powers to impeach the President, remove judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts, the Chief Election Commissioner, and the Comptroller and Auditor General in accordance with the procedure laid down in the Constitution of India. All legislations require the consent of both the Houses of Parliament. The Parliament is also vested with the power to initiate amendments in the Constitution of India.

Executive

The President serves as the Executive Head of the State and the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. Article 74(1) of the Constitution of India provides that there shall be a Council of Ministers, with the Prime Minister as its head to aid and advise the President.

The President appoints the Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers, Governors of States and Union Territories, Judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts, Ambassadors and other diplomatic representatives. The President is also authorised to issue Ordinances with the force of the Act of Parliament, when Parliament is not in session.

The President must consult the Council of Ministers and the Prime Minister before taking any executive decision. It is important to note that the Council of Ministers (usually known as the "Cabinet" and constituted of the members of the ruling political party/ alliance) and the Prime Minister (usually the leader of the political party/ consensus candidate of the alliance; also heads the Cabinet) are members of Parliament and, therefore, by convention, in their hands rest the legislative and executive powers of the Centre.

The federal units, ie, the States, have their own set-up in terms of legislatures (normally referred to as the "State Legislature") and state administrative wings similar to that of the Centre. Here, the Governor is the head of the Executive, though the real power rests with the Chief Minister and his/her Council of Ministers. There are certain territories in India that are not States, but are known as Union Territories and these are governed directly by the Centre.

The Constitution of India prescribes the separation of legislative and administrative powers between the Union and the States. Areas such as, defence, railways, maritime, interstate trade, airways, banking, etc, are under the jurisdiction of the Centre (Union List) and areas such as public order, police, agriculture, etc, fall under the jurisdiction of the States (State list). There is a third category of list also which is termed as the Concurrent List. It covers areas such as criminal law and procedure, economic and social planning, trusts, bankruptcy, etc, over which both the Centre and the States have legislative and executive powers, though in case of conflict between the two, the Centre's position prevails.

Judiciary

The Indian Judiciary as of today is a continuation of the British legal system established by the English in the mid-19th century. Before the arrival of the Europeans in India, it was governed by laws based on the Arthashastra, dating from 400 BC, and the Manusmriti from 100 AD. These were the influential treatises in India, texts that were considered authoritative legal guidance, however, till today the legacy of the British system is manifested from the fact that India falls into the genre of common law system. The procedure and substantive laws of the country, the structure and organisation of courts, etc, emanate from the common law system.

The Judiciary of India is an independent body and is separate from the Executive and Legislative organs of the Indian Government. The Judiciary in India provides the people of the nation the necessary "auxiliary precaution" required to ensure that the Government functions in favour of the people, for their amelioration and for the betterment of society.

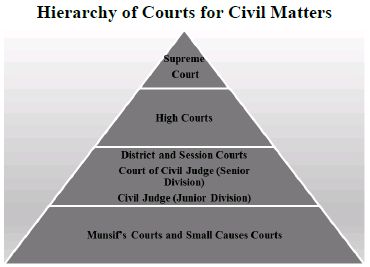

The judicial system of India is divided into four basic levels. At the apex level is the Supreme Court, situated in New Delhi, which, under the scheme of the Constitution of India is the guardian and interpreter of the Constitution of India, which is followed by High Courts at the State level, District Courts at the district level and Lok Adalats at the village and panchayat level. The Supreme Court and High Courts have the special constitutional responsibility of enforcing the "Fundamental Rights" of the citizen, as enshrined in Part III of the Constitution.

Below is a schematic representation of the hierarchy of courts in India:

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court has original, appellate and advisory jurisdiction. Its exclusive original jurisdiction includes any dispute between the Centre and State(s) or between States as well as matters concerning enforcement of fundamental rights of individuals. The appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court can be invoked by a certificate granted by the High Court concerned in respect of any judgment, decree, or final order of a High Court, in both civil and criminal cases, involving substantial questions of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution. Supreme Court decisions are binding on all Courts/ Tribunals in the country and act as precedence for lower courts. Under Art 141 of the Constitution, all courts in India are bound to follow the decision of the Supreme Court as the rule of law.

High Courts

High Courts have jurisdiction over the States in which they are located. There are at present, 23 High Courts in India.1 However, the following three High Courts have jurisdiction over more than one State: Bombay (Mumbai) High Court, Guwahati High Court, and Punjab and Haryana High Courts. For instance, the Bombay High Court is located at Mumbai, the capital city of the State of Maharashtra. However, its jurisdiction covers the States of Maharashtra and Goa, and the Union Territories of Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Predominantly, High Courts can exercise only writ and appellate jurisdiction, but a few High Courts have original jurisdiction and can try suits. High Court decisions are binding on all the lower courts of the State over which it has jurisdiction.

District Courts

District Courts in India take care of judicial matters at the District level. Headed by a judge, these courts are administratively and judicially controlled by the High Courts of the respective States to which the District belongs. The District Courts are subordinate to their respective High Courts. All appeals in civil matters from the District Courts lie to the High Court of the State. There are many secondary courts also at this level, which work under the District Courts. There is a court of the Civil Judge as well as a court of the Chief Judicial Magistrate. While the former takes care of the civil cases, the latter looks into criminal cases and offences.

Lower Courts

In some States, there are some lower courts (below the District Courts) called Munsif's Courts and Small Causes Courts. These courts only have original jurisdiction and can try suits up to a small amount. Thus, Presidency Small Causes Courts cannot entertain a suit in which the amount claimed exceeds Rs 2,000.2 However, in some States, civil courts have unlimited pecuniary jurisdiction. Judicial officers in these courts are appointed on the basis of their performance in competitive examinations held by the various States' Public Service Commissions.

Tribunals

Special courts or Tribunals also exist for the sake of providing effective and speedy justice (especially in administrative matters) as well as for specialised expertise relating to specific kind of disputes. These Tribunals have been set up in India to look into various matters of grave concern. The Tribunals that need a special mention are as follows:

- Income Tax Appellate Tribunal

- Central Administrative Tribunal

- Intellectual Property Appellate Tribunal, Chennai

- Railways Claims Tribunal

- Appellate Tribunal for Electricity

- Debts Recovery Tribunal

- Central Excise and Service Tax Appellate Tribunal

For instance, the Rent Controller decides rent cases, Family Courts try matrimonial and child custody cases, Consumer Tribunals try consumer issues, Industrial Tribunals and/or Courts decide labour disputes, Tax Tribunals try tax issues, etc.

It also needs special mention here that certain measures like setting up of the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) to streamline and effectuate the liquidation proceedings of companies, dispute resolution and compliance with certain provisions of the Companies Act, 20133 are also in the pipeline.

Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) in India

An interesting feature of the Indian legal system is the existence of voluntary agencies called Lok Adalats (Peoples' Courts). These forums resolve disputes through methods like Conciliation and Negotiations and are governed by the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. Every award of Lok Adalats shall be deemed to be a decree of a civil court and shall be binding on the parties to the dispute. The ADR mechanism has proven to be one of the most efficacious mechanisms to resolve commercial disputes of an international nature. In India, laws relating to resolution of disputes have been amended from time to time to facilitate speedy dispute resolution in sync with the changing times. The Judiciary has also encouraged out-of-court settlements to alleviate the increasing backlog of cases pending in the courts. To effectively implement the ADR mechanism, organisations like the Indian Council of Arbitration (ICA) and the International Centre for Alternate Dispute Resolution (ICADR) were established. The ICADR is an autonomous organisation, working under the aegis of the Ministry of Law & Justice, Government of India, with its headquarters at New Delhi, to promote and develop ADR facilities and techniques in India. ICA was established in 1965 and is the apex arbitral organisation at the national level. The main objective of the ICA is to promote amicable and quick settlement of industrial and trade disputes by arbitration. Moreover, the Arbitration Act, 1940 was also repealed and a new and effective arbitration system was introduced by the enactment of The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. This law is based on the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) model of the International Commercial Arbitration Council.

Likewise, to make the ADR mechanism more effective and in coherence with the demanding social scenario, the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 has also been amended from time to time to endorse the use of ADR methods. Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure, as amended in 2002, has introduced conciliation, mediation and pre-trial settlement methodologies for effective resolution of disputes. Mediation, conciliation, negotiation, mini trial, consumer forums, Lok Adalats and Banking Ombudsman have already been accepted and recognised as effective alternative dispute-resolution methodologies.

A brief description of few widely used ADR procedures is as follows:

- Negotiation: A non-binding procedure in which discussions between the parties are initiated without the intervention of any third party, with the object of arriving at a negotiated settlement of the dispute.

- Conciliation: In this case, parties submit to the advice of a conciliator, who talks to the each of them separately and tries to resolve their disputes. Conciliation is a non-binding procedure in which the conciliator assists the parties to a dispute to arrive at a mutually satisfactory and agreed settlement of the dispute.

- Mediation: A non-binding procedure in which an impartial third party known as a mediator tries to facilitate the resolution process but he cannot impose the resolution, and the parties are free to decide according to their convenience and terms.

- Arbitration: It is a method of resolution of disputes outside the court, wherein the parties refer the dispute to one or more persons appointed as an arbitrator(s) who reviews the case and imposes a decision that is legally binding on both parties. Usually, the arbitration clauses are mentioned in commercial agreements wherein the parties agree to resort to an arbitration process in case of disputes that may arise in future regarding the contract terms and conditions.

While the judicial process is largely considered fair, a large backlog of cases to be heard and frequent adjournments result in considerable delays before a case is decided. However, matters of priority and public interest are often dealt with expeditiously and interim relief is usually allowed in cases, on merits.

Footnotes

1. http://indiancourts.nic.in/index.html

2. Section 18 of The Presidency Small Cause Courts Act, 1882 http://indiankanoon.org/doc/997218/ and http://www.manupatrafast.in/ba/fulldisp.aspx?iactid=1496

3. The Companies Act, 1956 has now been replaced with Companies Act, 2013 which has come into effect from April 1, 2014.

© 2017, Vaish Associates Advocates,

All rights reserved

Advocates, 1st & 11th Floors, Mohan Dev Building 13, Tolstoy

Marg New Delhi-110001 (India).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist professional advice should be sought about your specific circumstances. The views expressed in this article are solely of the authors of this article.