- within Family and Matrimonial topic(s)

- in India

- within Family and Matrimonial topic(s)

- in India

- within Family and Matrimonial, Criminal Law and Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring topic(s)

- with readers working within the Healthcare, Retail & Leisure and Law Firm industries

The right to life, enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, guarantees every individual the right to live with dignity. Over time, this provision has been interpreted by the courts to extend beyond mere existence, encompassing the right to die with dignity as well. In a series of landmark rulings, the Supreme Court of India has acknowledged that the right to life includes the autonomy to make decisions regarding one's own body and medical treatment, even in end-of-life situations. This has brought the concept of a "Right to Die with dignity"1 as an intrinsic facet of Article 21.

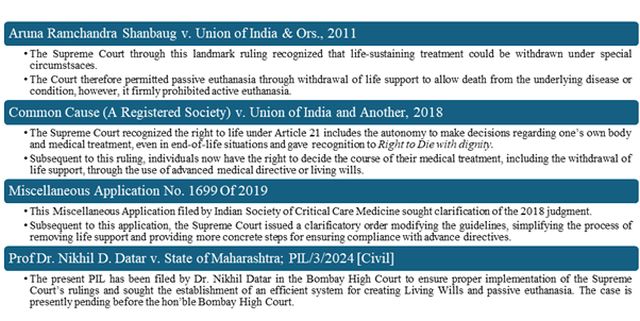

The recognition of the said right has laid the foundation for the legal validity of Living Wills, allowing individuals to decide in advance how they wish to be treated when they are no longer in a position to make decisions for themselves. Historically, the right to die was not recognized in India. However, through a series of landmark judgments, the Supreme Court acknowledged an individual's right to die with dignity, alongside their right to end prolonged suffering. This gradual recognition of such rights became apparent in the pivotal 2011 case of Aruna Shanbaug v. Union of India2 wherein the Supreme Court permitted passive euthanasia. Passive euthanasia refers to the withdrawal of life support to allow death from the underlying disease or condition, as opposed to active euthanasia, which involves administering lethal substances to cause death. The court, while permitting passive euthanasia, firmly prohibited active euthanasia. This case laid the foundation for subsequent discussions on end-of-life care and the legal recognition of Living Wills in India.

A Living Will, also known as an Advanced Medical Directive, is a legal document that allows an individual to express their wishes for medical treatment in the event they become incapacitated with minimal prospect of recovery. It outlines the person's desire to pass away naturally without being sustained by medical interventions. This directive not only guides healthcare professionals on the treatment the individual would prefer when unable to make decisions but also alleviates the emotional burden on family members and minimizes potential conflicts over the patient's care.

The legal validity of Living Wills in India was deliberated by the Supreme Court in Common Cause v. Union of India3, wherein the Court upheld the constitutionality of advance directives and set forth comprehensive guidelines for their implementation.

The court emphasized the significance of honoring valid advance directives, provided they clearly reflect the patient's wishes to refuse treatment. Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and liberty, was interpreted to include the right to dignity in both life and death. The court remarked that concerns of misuse, raised by the Law Commission of India vide Law Commission reports4, were insufficient to reject advance directives. Instead, safeguards were proposed to prevent exploitation.

The Supreme Court, thus, outlined these safeguards, specifying who can create an advance directive, its contents, recording and preservation procedures, and the course of action if medical treatment withdrawal is denied by a medical board.

It was clarified that an advance medical directive can be executed and will be legally binding when executed by an adult possessing full mental capacity, capable of comprehending the document's ramifications and purpose, and able to effectively communicate. Such execution must be voluntary, devoid of any form of coercion, inducement, or compulsion, and must be drafted with complete knowledge and should reflect the individual's understanding and willingness.

Subsequent to this ruling, individuals now have the right to decide the course of their medical treatment, including the withdrawal of life support, through an advance directive.

Figure 1: Chronological Overview of the Evolution of the Right to Die with Dignity

However, despite Supreme Court's ruling, the complexity of the procedure laid down and difficulties faced by a large number of doctors in implementing the directions laid down by the Supreme Court led to filing of a Miscellaneous Application by Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine5 seeking clarifications on the 2018 Supreme Court judgment.

In 2023, the Supreme Court issued a clarificatory order modifying the guidelines, simplifying the process of removing life support and providing more concrete steps for ensuring compliance with advance directives.

According to the 2023 order, the directive must specify in unambiguous terms the individual's decision to withhold or discontinue treatment. The document should also name a guardian authorized to make decisions and allow for its revocation. For patients without advance directives, terminally ill individuals suffering from incurable conditions can still opt for passive euthanasia, provided a structured medical review process is followed.

In 2024, Dr. Nikhil Datar, a prominent advocate for Living Wills, filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL)6 in the Bombay High Court to ensure proper implementation of the Supreme Court's rulings. Dr. Datar, along with two professors, sought the establishment of an efficient system for creating Living Wills and passive euthanasia. The state government in its response mentioned that over 400 officials had been appointed across local bodies to manage living wills.

However, Dr. Datar highlighted the challenges he faced when trying to submit his living will. One such challenge was that the certifying officer was unable to provide clear guidance on how the document could be retrieved after 20 years. It was further pointed that the secondary medical board which must be formed to verify the primary board's decision was not incorporated, without which the process remains incomplete.

The Bombay High Court has presently questioned why the state had not created a permanent secondary medical board, suggesting that each district's CMO could simply nominate a doctor for the role. The court has requested a detailed explanation from the state government and has allowed Dr. Datar to add the National Medical Commission (NMC) and the Union Health Ministry as parties to the case. The case is presently pending before the hon'ble Bombay High Court.

Key Takeaways

The following are the key takeaways pertaining to Living Will/ Advanced Medical Directive under the current legal framework –

- The executor of a Living Will must provide a copy of the advance directive to named Nominee(s) and the family physician, if applicable, and to a designated custodian (competent officer of the local Government or Municipal Corporation or the Municipality or Panchayat, as the case may be). They may also integrate it into digital health records, if any.

- When a treating physician is made aware of a terminally ill patient's advance directive, they must verify its authenticity from digital or custodial records.

- Upon confirmation, the physician has to inform the Nominee(s) about the illness, treatment options, and make sure the Nominee(s) understand the consequences of the directive.

- Once it has been confirmed that there is no other option, a Primary Medical Board, led by the treating physician and specialists, shall assess the directive's instructions and verify whether it is viable to proceed with the instructions of the directive.

- Subsequently, a Secondary Medical Board, including include a registered medical practitioner nominated by the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of the district and two experts with at least five years of experience, reviews the decision.

- If the Primary Board rejects the directive, the Nominee(s) can request a Secondary Board review.

- The Secondary Board also evaluates the executor's capacity to understand and communicate, seeking Nominee(s)' consent if necessary.

- The hospital must then inform a judicial magistrate of the decisions from medical boards and Nominee(s)' consent before withdrawing treatment being provided to the executor/ executrix.

- If the Secondary Board denies withdrawal, the treating doctor or hospital staff may file a petition with the jurisdictional high court.

This process ensures proper adherence to the advance directive's instructions and safeguards the executor's wishes regarding medical treatment.

Conclusion

A Living Will serves as a crucial legal instrument for individuals to express their medical treatment preferences in scenarios where they are incapacitated and unable to communicate their wishes. It primarily allows for passive euthanasia, where life-supporting treatments can be withdrawn, thus permitting natural death. The Supreme Court of India, through significant rulings like Common Cause v. Union of India, has legally recognized the right to create a Living Will, reinforcing an individual's right to die with dignity. However, the legal framework around Living Wills is still developing, with procedural complexities and practical challenges slowing down its widespread implementation. Key issues include the lack of awareness among the public and medical professionals, as well as delays in establishing essential mechanisms like medical review boards.

For individuals looking to create a Living Will, it is essential to identify at least two trusted individuals who can serve as surrogate decision-makers. These individuals, who may be family members, friends, or neighbours, will be empowered to make decisions on behalf of the person if they lose decision-making capacity. it is vital to ensure the document is drafted with informed consent, free from coercion, and witnessed by two independent individuals and subsequently attested before a notary or gazetted officer.

The directive should be deposited with designated custodians, and if possible, integrated into digital health records to guarantee easy access when needed. Additionally, it is important to understand the revocation process, which allows the directive to be modified or cancelled at any time. As the understanding and legal structure around Living Wills evolve, it will play a critical role in protecting patient autonomy and ensuring that end-of-life care aligns with personal wishes, providing dignity in the final stages of life.

The Supreme Court's guidelines on Living Wills have paved the way for individuals to exercise greater autonomy over their medical care, ensuring dignity in death. However, the framework's implementation has faced several challenges. The creation of Living Wills remains a developing concept in India, and there are ongoing legal and procedural obstacles that need resolution to ensure its effective use.

Living Wills differ fundamentally from Last Wills and Testaments. While the latter governs the distribution of a person's assets after death, a Living Will takes effect during the person's lifetime when they are incapacitated and unable to communicate their medical preferences.

Dr. Nikhil Datar's advocacy has been instrumental in raising awareness about the importance of Living Wills. His submission of the first legally compliant Living Will marks a significant milestone, yet his experience underscores the need for better mechanisms to implement these directives. As Living Wills gain acceptance, the legal landscape will continue to evolve, providing individuals with more clarity and support in exercising their rights to autonomy in healthcare.

Footnotes

1. Common Cause (A Registered Society) v. Union of India and Another, (2018) 5 SCC 1, Supreme Court (India), 9th March, 2018

2. Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union of India & Ors., 2011 (4) SCC 454, Supreme Court (India), 7th March 2011

3. Supra, Note 1

4. Law Commission of India, Medical Treatment to Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners), Report No. 196, March 2006 and Law Commission of India, Passive Euthanasia – A Relook, Report No.241, August 2012

5. Miscellaneous Application No. 1699 Of 2019 in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 215 Of 2005, filed by Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine seeking clarification of the judgment reported in Common Cause (A Registered Society) v. Union of India and Another (2018) 5 SCC 1

6. Prof Dr. Nikhil D. Datar v. State of Maharashtra, PIL/3/2024 [Civil]

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.