- within Employment and HR topic(s)

- in Ireland

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure and Law Firm industries

- within Employment and HR topic(s)

- in Ireland

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Intellectual Property, Energy and Natural Resources and Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

Probation in employment contracts refers to a temporary period during which an employer evaluates a newly hired employee's performance, suitability, and fit within the organization before confirming permanent employment. During this period, probationary employees do not receive statutory benefits typically available to regular employees, such as provident fund contributions, gratuity, insurance, etc. However, they are entitled to essential protections against discrimination and harassment. Recent case studies show that few employers tend to include unfair terms in probation clauses, potentially exploiting probationary employees who generally have less bargaining power than employers. Therefore, it is crucial to analyse this concept in India in terms of legal sanctity and enforceability, identify any gaps, and propose solutions to safeguard the rights and interests of probationary employees.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK:

India does not have a specific legislation governing probation and hence in practice, reliance is placed on the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act, 1946 read with the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Central Rules, 1946 ("IESO Rules"), which lays down guidelines for conditions of employment, including the process of probation and confirmation and applies to organizations or companies with at least 100 or more workers employed, or 50 or more workers in cases where the Central Government is the appropriate authority. The Model Standing Orders ("MSO") provided under the IESO Rules define a "probationer" to be a workman who is provisionally employed to fill a permanent vacancy in a post and has not completed three month's service therein. The MSO also provides for termination of employment of a probationer which can be done without notice. In practice, companies/establishments/employers incorporate the probation clause in employment agreements in accordance with the terms of the aforesaid provisions of the MSO. However, the probation tenure varies from employer to employer across private and public sectors. In this context, it is relevant to highlight that the Industrial Relations Code, 2020 ("Code"), enacted in 2020, has extended the applicability of Standing Orders to all industrial establishments intending to create uniformity in employment conditions across industries.

In practice, the employers typically include a probation clause in the employment contract that clearly outlines the duration, notice and termination terms. However, while incorporating such a probation clause, the employer must ensure that it is not unreasonable, ambiguous or exploitative in nature. Apart from contractual rights, a probationer's continuous service for a certain period may also entitle him/her to benefits under certain labour and employment laws. For instance, if a probationer completes 240 days of continuous service (even on probation), he/she will get covered under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 ("ID Act") and thus, if an employer then decides to terminate the probationer's services due to unsuitability, they must comply with Section 25-F of the ID Act, which requires providing at least one month's written notice with reasons for termination or paying the probationer in lieu of such notice and if no notice is given, the employer must compensate the probationer with fifteen days' average pay and notify the appropriate government or authority. Failure to adhere to this procedure can lead to industrial disputes or litigation under the ID Act. Additionally, reference can also be made to the Shops and Establishment laws of various states which grant benefits to employed persons upon completion of a specified period of service. For example, under the Delhi Shops and Establishments Act, 1954, an employed person who completes three months of continuous employment is entitled to receive at least one month's notice in writing or wages in lieu of such notice, before dispensation of his services except if the same is due to his/her misconduct in which case he/she has to be given an opportunity to explain the charge or charges alleged against him in writing.

JUDICIAL FRAMEWORK:

In addition to the above, the Indian judiciary has also played a crucial role in shaping the concept of probation by resolving ambiguities and ensuring the protection of probationers' rights. This includes clarifying the permissible duration and extension of probation period and recognizing the importance of fair procedures for dismissal or termination. However, while doing so the judiciary has also attempted to strike a balance between the rights of employer and employees as is evident from cases cited in the preceding paragraphs:

I. Maximum Period & Extension of Probation:

The IESO Rules prescribe three months as probationary period which may be further extended by employers to a limited extent depending on the job specifications but not beyond a reasonable time frame. Even if an employment contract provides for a comparatively longer probation period, the same cannot be unreasonably long (including extensions). In this context reference can be made to the case of Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Senior Secondary School vs J.A.J. Vasu Sena wherein the Hon'ble Supreme Court observed that prolonged periods of probation (like five years in this case), can overage the chances of the employee getting suitable future employment. Observing the situation, the Court directed the school to pay compensation to the aggrieved probationer.

II. Dismissal/ Termination:

According to the IESO Rules, a probationer can be terminated without notice during the probation period. Therefore, if an employer finds the performance of an employee on probation unsatisfactory or determines them to be unfit for the job, they have the right to terminate the employee before the probation period ends, without providing any notice. However, this is subject to specific legislations that may require notice for termination upon completion of stipulated period of continuous service in an organisation. Additionally, as per the recent judicial trends, if a termination/dismissal order is stigmatic in nature (including accusations of misconduct), the same must provide reasons. In this context, relevant cases include:

In Progressive Education Society v. Rajendra , the Supreme Court of India noted that it is well-established law that the appointing authority has the discretion to terminate a probationer's services if their performance is found unsatisfactory during the probation period. Unless the termination involves a stigma or the probationer is asked to explain any deficiencies that lead to termination, the employer is not required to provide any explanation or reason for the dismissal.

In the case of Pavanendra Narayan Verma v. Sanjay Gandhi PGI of Medical Sciences , the Apex Court observed that simple termination from probation is not punitive in nature and hence doesn't require any kind of notice before termination.

From the above, it is evident that subject to legislations applicable upon completion of continuous period of service, probationers have minimal to no rights regarding termination when it is based on dissatisfaction with their performance or unsuitability for the job. Employers are not required to justify such terminations to probationers. However, if the termination is punitive or stigmatic in nature, it is mandatory for the employer to conduct a disciplinary inquiry according to established procedures, providing the probationer with reasons and an opportunity to be heard. Without following these procedures, such termination or discharge based on accusations, would be deemed illegal/improper in which case, the employer may be required to compensate the dismissed probationer.

CONFIRMATION STATUS:

The confirmation status of an employee after completion of probationary period depends on the terms outlined in the employment contract. It may require a formal confirmation letter, or in the absence of such a provision, confirmation may be deemed to have occurred.

ENFORCEABILITY OF PROBATION CLAUSES:

The enforceability of probation clauses often depends on the clarity and precision of the terms stated in the employment contract. Courts generally uphold well-defined probation clauses that explicitly outline the duration, conditions, and expectations during the probationary period. However, if a probation clause is unreasonable or exploitative, such as allowing for an indefinite extension of the probation period, it will not be enforceable under the law.

Even though the legal framework including legislative and judicial developments address the issues of probation at length, it is pertinent to examine the standard probation terms that are generally incorporated in employment contracts of other countries, as discussed in the next segment.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS:

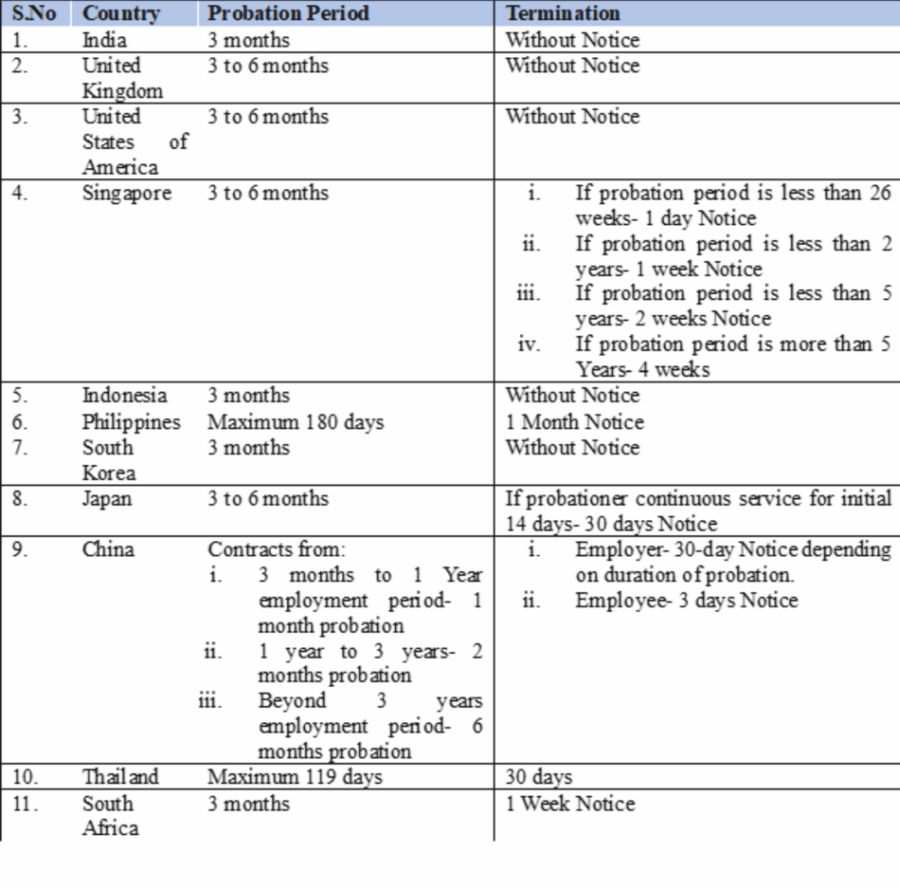

The concept of probation is recognized across various jurisdictions, however, the terms and legal implications of the same vary significantly. A comparative analysis of probation clauses specifying tenure and notice/termination terms in various countries is provided in the table below:

WAY FORWARD:

The author believes that employers should provide a termination notice to all employees, whether they are regular or on probation as such formal communication specifying the notice period, allows employees to explore new opportunities during that time frame and helps them mitigate sudden unemployment crisis. This also helps the employers maintain records and transparency. On analyzing the above table, it is evident that as compared to India, some countries have adopted a more lenient approach in terms of probation periods and notice requirements for terminating probationary employees. Adopting a similar approach in India could help protect the interests of probationers across various sectors.

The author is also of the view that although the judiciary has significantly contributed to the development of probation-related jurisprudence, there is significant disparity in probation terms especially in private sector employment contracts, highlighting the pressing need for standardized directions (in the form of clarifications) to govern probationary employees across sectors. Such directions should require employers to include a standard probation clause in employment contracts and cover aspects such as fixed probation duration, notice mandates, requisite notice period, termination and other relevant terms. Furthermore, such a change should be mandated at the central level and uniformly enforced across all states and sectors/industries, providing legal protection and removing ambiguities regarding the rights of probationary employees.

From a contractual standpoint, both employers and employees should be responsible for executing an unambiguous employment contract. This contract should outline the probation duration, potential extensions or criteria for confirmation, authorized leaves, salary details, notice, grounds for dismissal, and conditions for termination during the probation period. Such clarity ensures that both parties understand each other's expectations, rights and obligations during probation.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]