- within Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- in Asia

- in Asia

- within Transport topic(s)

The first 100 days of Donald Trump's US administration have already caused considerable uncertainty as to where the USA is heading. This also raises questions about the use of cloud services from US hyperscalers: Is the data still safe from the US authorities? And could the US administration weaponize cloud providers for their own purposes given Europe's dependence? We have expanded our standardised method for assessing the risk of foreign lawful access so that these questions can now also be assessed and documented.

Looking back: In 2019, I was commissioned by a large Swiss bank to answer the question of which technical and organisational measures are required when using a US cloud in order to reduce the residual risk of US lawful access to an acceptable minimum under Swiss banking secrecy based on laws such as the US CLOUD Act. I developed a statistical method with which the risk could be divided into 19 conditions and systematically addressed. In 2020, I published the method in the form of an Excel spreadsheet as open source (available here with an FAQ).

This approach became known in Switzerland as the "Rosenthal method" and is now considered the standard procedure for assessing the risk of access by foreign authorities in Switzerland and beyond. Banks and other professional secrecy holders use it, as do public authorities if they want to use foreign cloud providers but are subject to special confidentiality obligations. The method is no longer only used in relation to the USA, but also to assess other jurisdictions. With the right measures, the probability of foreign authority access from the USA and some other countries with a comparable legal system can be reduced to a (theoretical) value of generally less than 1.5 per cent for a five year period, as we have seen from numerous workshops. The issue therefore seemed to be more or less "under control" given that the risk-based approach is now generally accepted.

Current fears regarding the US cloud

However, developments in the USA since US President Trump took office have once again raised fears that the security and stability of US hyperscalers may no longer be as strong as in the past:

- It began with the news that Trump had reportedly asked three Democratic members of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) to resign or dismissed them. This raised the question of whether the board is still capable of acting (which it has apparently answered in the affirmative for the time being). Among other things, it monitors the activities of the US intelligence services and also performs certain tasks within the framework of the CH-US/EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF), namely as a body to be consulted when appointing the "DPF Court" and in assessing the effectiveness of the DPF (more on this here). Although the DPF is not legally dependent on the PCLOB, there have been rumours in some quarters that the existence of the DPF is now in jeopardy. So far, it has continued to exist unchanged and we do not currently see any efforts by the data protection authorities or the European Commission to overturn its recognition..

- Another fear is that the Trump administration could be tempted to access the data stored in the cloud by European organisations on pretextual grounds (allegedly serious criminal offences). Although there are a number of obstacles to this if it is done applying the right measures, some of these only protect customers if the US authorities comply with US law and the courts also enforce it if necessary. In view of the developments of recent months with regard to upholding the principle of the rule of law and separation of powers, however, some are beginning to doubt whether they would be compliant and whether the hyperscalers are willing to resist any such requests from the US government despite their contractual obligations. The spectrum of opinions here is broad. No cases of such attempted lawful access requests concerning legitimate European cloud customers or breach of related contractual obligations are known to date.

- Finally, there are fears that the US could impose requirements on US-based hyperscalers to enforce its interests that would ultimately no longer be acceptable to their customers in Europe but where these customers would have no alternative but to submit to them or fulfil the associated political demands due to their dependency. Such requirements could be the obligation to store or purchase services directly from the USA (instead of from Europe) or the penalisation of certain countries or organisations through export controls or sanctions that affect cloud services. Although the contracts with hyperscalers regularly include provisions against lawful access by foreign authorities, they also make their services subject to the proviso that they do not violate any applicable law. The contracts therefore offer a backdoor for such attacks by the US government. However, no such endeavours have been reported so far.

The reaction of the hyperscalers

The US hyperscalers seem to have been caught on the wrong foot by the current developments in the USA. We certainly got the impression that they too are at a loss as to how to deal with the new situation under the Trump administration. We know that they have already been confronted with many enquiries on the subject, even if it seems that most customers simply want to wait and see how things develop for the time being (see also below).

Last week, Microsoft was the first provider to take the plunge and attempted to shore up the confidence of its customers with a well-orchestrated announcement of initial measures. This essentially consisted of three elements: The message that Europe is important to Microsoft and it is therefore investing heavily in the expansion of infrastructure, that Microsoft will defend itself against all access attempts, including in court, and that partnerships have been formed to enable the operation of the European cloud to continue independently of the parent company in the event of an emergency. The first two points are nothing new. Microsoft already made it clear several years ago with an extensive "defend-your-data" clause that it would fight US authorities' access to European data up to the highest court if necessary. Such a clause is now the standard requirement for cloud contracts (see also our sample clause) and actually plays a central role in the risk assessment. In certain contracts in the public sector, Microsoft's contractual commitments go even further.

What was new was the announcement of the contingency plan in the event that Microsoft would be legally forced to discontinue its cloud services in Europe, whereby the operation of partners in Europe should be able to continue, with the source code of the cloud software being securely stored in Switzerland for this case (we assume that Switzerland was chosen for legal reasons, among other things, because it offers special legal provisions that provide special protection against access by foreign authorities). In future, this should also be stipulated in customer contracts.

This announcement is undoubtedly a skillful move, but it cannot hide the fact that there are more subtle threat scenarios and that even the emergency scenario would not be a long-term solution. Of course, we also don't know the details of the contingency plan. Microsoft and Google have already offered the option of "sovereign" cloud data centres that are operated by legally independent companies; Google even offers clients to run their own cloud based on the software from Google. However, independent operation is only the minor challenge. In addition, the operation of the cloud as a whole would not necessarily be prohibited in conceivable scenarios, but new restrictions could also lead to it no longer being acceptable for clients. For example, if certain features that protect against access by the US authorities were no longer available outside the US, or certain services would now have to be provided from the US.

The bigger challenge is the further development of the software stack on which the cloud is operated: For security reasons alone, this must be constantly maintained, which requires corresponding expertise. If this can only be found in the USA, the dependency remains. The same applies to activities accompanying the operation, such as analysing security threats. This raises the question of whether, depending on developments in the USA, hyperscalers could sooner or later be forced to relocate their expertise from the USA to other countries if their business in the rest of the world were otherwise jeopardised. In any case, it is rumoured that Microsoft's business outside the USA is already larger than its domestic USA business. We should also remember that, as a rule, large companies do not act ideologically, but purely opportunistically: Business comes first. This can affect all sides. The US government would therefore be well advised to treat hyperscalers with kid gloves. Of course, kid gloves have not been their strong point so far, which brings us back to the issue of uncertainty.

Further development of our assessment method

With this in mind, we have expanded the method in order to be able to map these uncertainties as part of risk assessments and thus enable proper assessment and documentation of the risks.

The method already covered the aspect of foreign lawful access. It is agnostic, i.e. not focussed on a specific legal system and also not dependent on how this legal system functions, i.e. whether the separation of powers is respected or the principle of the rule of law applies. In particular, it can also be used to assess the current situation in the USA, however it is assessed on these points. No adjustments were therefore necessary with regard to the method as such. Yet, it could only depict a single state or overall assessment for the entire assessment period, and this may be insufficient in terms of the volatility of the current situation or at least make an objective overall assessment more difficult. What the method also does not depict are risks in relation to safeguarding the continuation of business through foreign legal developments. To date, this has been a subordinate issue in the perception of most users, at least in relation to the USA.

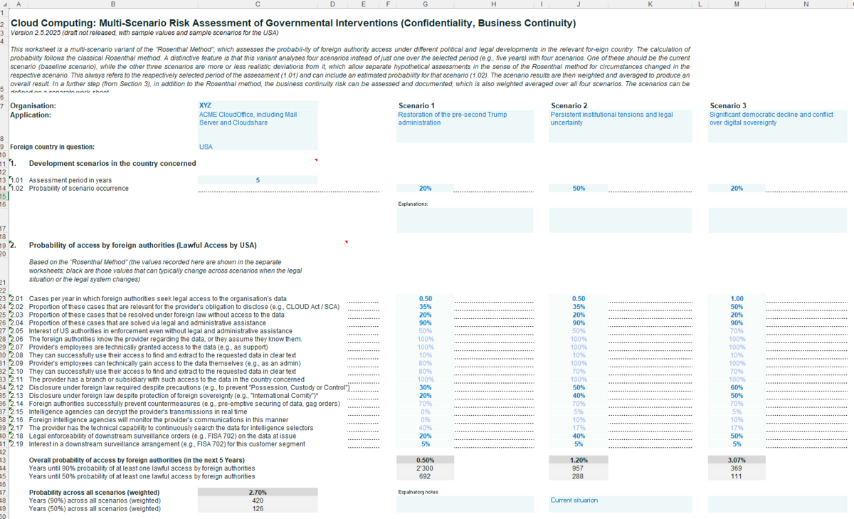

We have therefore expanded the method in two respects, namely by adding a scenario-based assessment and an assessment of going concern risks. The extended Excel can be downloaded from the previous address here and is available in English and German (see worksheet "Multi-Scenario ..."). The current version is a draft for public comment. The content in blue is only for illustration purposes how to fill out the worksheet (the scenarios contained therein do also not necessarily reflect our opinion or forecast); everyone using the method should include his or her own view of the situation.

New: Scenario-based assessment of foreign lawful access

risk

The method now works with four scenarios of how the situation in the USA (or any other country) could develop over the chosen period and assesses the probability based on these four scenarios. These are described in a worksheet (we have provided four sample scenarios for the USA 2025-2030, which can and should be adapted or adopted according to your own assessment).

- In a first step, the probability of occurrence of each scenario must be assessed (these should add up to 100 per cent).

- In a second step, the existing factors are then assessed for each of these scenarios using the existing method. For example, the current "pre-Trump" baseline scenario can be transferred from an existing assessment on the worksheet to the first scenario. It is then possible to assess and record how the assessment is likely to change in the relevant points for the other three scenarios. Naturally, only those factors that are dependent on the political and legal situation in the USA or the country in question will change. These are printed in bold. Note: For the value in section 2.13, the inverted percentage value is used to make it easier to understand, i.e. if the original method states 80%, 20% should be entered here. We have summarised the longer description from the original method; nothing has changed in terms of content.In a third step, this set of four assessments is then used to calculate an average weighted probability according to the probability of occurrence of each scenario, which ultimately serves as the final result. Also, the number of years is calculated until at least one case must be expected with a 50 or 90 % probability. The cantonal government of Zurich, for example, has set forth that a new risk decision by the cantonal government is only necessary for the 90% value if this value falls below 100 years, which corresponds to a probability of occurrence of around 10% over five years. Everyone has to set their own limits, though.

The previous Excel workbook is still used to calculate the specific values (the four worksheets used for this are hidden in Excel). So nothing changes in the method.

New: Assessment of business continuity risks

The method now also allows the business continuity risk to be assessed, i.e. the possibility that the cloud service under discussion may not be available or no longer available in the required manner due to developments in the USA and can therefore no longer be used. This risk is of course not new and we have regularly dealt with it in our cloud consulting for public and private organisations: Cloud services or important aspects (e.g. storage in Switzerland or specific functions) can be discontinued or changed abruptly if legally required, services can become the victim of technical failures or cyber attacks.

In the eyes of some, there is an increased risk that the US government will exploit Europe's dependence on US hyperscalers for political purposes or otherwise take measures that jeopardise the continued use of hyperscalers. Everyone must judge for themselves the likelihood of such developments. It is also conceivable that European governments will mount a defence. The same applies to precautions taken by the cloud providers themselves, such as those of Microsoft described above. These additional risks and countermeasures due to the political situation in the USA can now also be assessed:

- The first step is to indicate what the consequences would be if an organisation had to stop using the cloud in the short term, depending on whether it has a "plan B". Every organisation should have already made this assessment as part of its cloud risk management. However, we see in our advisory work that many projects are weak on this point. For example, when using M365, we recommend an emergency plan that provides for at least a bare minimum operation of corresponding functions outside the cloud and backups that are not stored in the cloud (see also below).

- In a second step, an assessment is made of what other possible, previously unassessed circumstances could occur that could prevent or hinder the continuation of the cloud solution, for example if the US government uses continued access as a means of exerting pressure to enforce political demands in another area. The probability of these circumstances occurring is assessed for all four scenarios when using our method.

- In a third step, possible countermeasures can be assessed, such as the EU forcing hyperscalers to organise their operations in Europe in such a way that they are independent of the US or the hyperscalers, on their own initiative, decoupling their European business from the US. For all four scenarios, it is also possible to assess how likely it is that such a measure will be taken that is actually effective. This probability is then offset against the probabilities from the second step.

- Finally, the results from all three steps are used to calculate an overall risk per scenario, from which a weighted average risk is determined and reported. In contrast to the assessment of access by the authorities, where only the probability of occurrence is assessed (because the assessment is based on the principle that each access represents the maximum severity), the risk (severity x probability of occurrence) is calculated in the case of business continuity, based on a risk matrix of 4 x 4.

Here, too, we have entered sample values. Each organisation must make its own assessment of the probabilities. The sample values are for illustrative purposes.

How the market assesses the current situation

We have already received various enquiries about how organisations should deal with the political uncertainties and developments in the USA in relation to their cloud projects with US hyperscalers. It turns out that the private sector seems to be much less concerned than the public sector. This is not surprising: when the state goes into the cloud, issues such as "digital sovereignty" and the US CLOUD Act play a greater role in the minds of commentators, politicians and data protection authorities than when it is a bank, industrial company or retailer. The fact that developments in the USA increase the risk of cloud use is barely disputed. However, opinions differ as to whether this increase is sufficiently material to alter things. In many cases, the public debate is also polemical and emotional. This is not surprising; even the earlier debate about the risk of access under the US CLOUD Act was largely not objective and based on false assumptions about the legal situation. This is unfortunate because the current situation in the US does indeed raise relevant questions that we should consider:

- It is (still) not true that the US CLOUD Act gives US authorities free access to data stored in the cloud. However, it is true that protection against such access is based, among other things, on applicable US law and is dependent on the authorities and courts complying with it – or at least the courts doing so. Protection therefore requires at least a functioning separation of powers. Against this backdrop, the Trump administration's efforts to undermine this are relevant for the risk assessment. We do not know how the situation in the USA will develop, but anyone who wants to carry out a conscientious risk assessment today must take these uncertainties into account. This can be done using either the existing or the extended method; in the latter case, particular consideration can be given to how the situation in the USA might change in the next few years, as this is of particular concern to many observers, rather than the situation today. In the new scenarios, not only can the reliability of the legal arguments against lawful access be assessed, but also the question of whether the US government has an increased interest in actual access to European cloud data or even an expansion of foreign mass surveillance. In our opinion, doubts are justified on both counts, even if Donald Trump is said to not be particularly reticent about taking action against others. It should be borne in mind, though, that US law provides him with much more convenient and effective means of putting pressure on Europe in the area of the cloud, for example, should he wish to do so (see below). We do not see any motives or indications for an expansion of signal intelligence abroad, for example. Nor do we see why the government under Trump should have an increased interest in using legal means via a cloud provider to access data on the mail server of a local Swiss government, a social security authority or the federal government, just to give some examples. This does not fit his profile.

- European companies usually conclude cloud contracts with Microsoft, AWS and Google with the European subsidiaries of the three hyperscalers. It seems unlikely to us and most of the customers we talk to that they will stop or restrict the services they provide to European companies due to political developments in the USA. However, it has become conceivable that the Trump administration could, for some reason, conclude that Europe's dependence on cloud services could be weaponized to enforce unrelated claims against individual countries or industries. But here, too, a sober view is required: if a country's cloud users were actually taken "hostage" by the Trump administration, for example for the purposes of a trade war, what would that mean for individual users? Should they avoid the cloud as a precaution due to such a risk? Or should the opportunistic calculation be completely different? If an estimated half to three quarters of all mail servers are already running on Microsoft software today and will then also be in the cloud, Microsoft is "too big to fail" in this respect. If access to this resource were actually threatened, wouldn't customers take the view that it was up to their government to protect them – on the principle of "the hostage never pays the ransom"? Of course, this way of thinking can be described as irresponsible. Yet, our impression is that this is what it actually boils down to. The individual, average customer who decides in favour of M365 like "everyone else" can hardly be blamed because many will consider this the easiest way to fulfil their need. This may also explain why hardly any customers think about the scenario of a world without Exchange Online – to take one example. The path of the herd is chosen and, from a purely opportunistic point of view, relying on herd protection is not entirely wrong for many private and public organisations. For this reason, our method allows us to reflect this reality, which in our experience also exists – just as everyone wants to do for their own case. Another question is whether the state, for its part, sees a need for regulation, as it does elsewhere, for example, where there are "too big to fail" risks. The argument that there is competition between the three major cloud providers does not solve all the problems, given the fact that they are all US-based. However, we do not have the impression that the pressure to act is currently high enough that the state sees a need to intervene.

- Open source alternatives to the offerings of the major cloud providers are repeatedly mentioned in public; for public administration, the example of Schleswig-Holstein is regularly cited, but in Switzerland the Federal Court should also be mentioned. However, we have the impression that customers have so far shown little or no interest in withdrawing from the cloud, particularly from M365. Behind closed doors, even various self-confessed open source supporters we have talked to, did not believe that public authorities with M365 or plans to introduce this solution will leave the cloud again in the short or medium term. The situation in the USA has not changed this so far and is unlikely to change it any time soon, unless there are more dramatic developments. There are two consequences of the situation in the US, though: Firstly, there is a growing need to assess the uncertainties created by the developments in the USA objectively, not emotionally. This has already been one of the main reasons for using our method. Secondly, more and more public authorities are realising that, in addition to the issue of lawful access from abroad, ensuring business continuity management is just as, if not more, important. Especially among some data protection authorities, this aspect has been overlooked due to the sometimes-blind focus on access by foreign authorities – we have repeatedly pointed this out. In practical terms, this means that both public and private organisations should not move to the cloud without a "plan B" or even a "plan C". On the one hand, this must include a backup of all data outside the cloud and, on the other hand, a way of being able to offer the basic functions of M365, for example, even if the cloud is no longer available as required in the medium or long term for whatever reason (which might not necessarily have anything to do with Trump). It should be possible to realise this with reasonable effort, especially for mail and file server applications, even if such emergency solutions will not come close to the convenience of today's solutions. The crux of such emergency solutions is not the software, but the provision of the necessary computer capacities and the creation of a plan for emergency migration; in Switzerland, the Confederation's plan for a Swiss Government Cloud (which should also be available to cantons and municipalities) and data centres of Swiss providers, which certainly exist, are particularly suitable for public authorities. Of course, maintaining computing and storage capacities does have a cos. In our method, such business continuity measures can be mapped in the first block, where the organisation-specific business continuity risks are assessed and documented. We have had this topic regularly assessed in our Cloud Compliance and Risk Assessment "CCRA" in the cloud projects in which we have advised and continue to advise (see box). In practice, we saw a much greater need for action here than with the risk of access by foreign authorities.

To summarise, we recommend that public administrations in particular consider the potential impact of political developments in the USA when using US cloud offerings, evaluate these and document them accordingly. In most cases, this will at least at the moment not result in any changes to the procedure, at least if there is a "plan B", but then homework has already been done. The effort is ultimately limited. As before, n practice workshops in which the various internal stakeholders work out a joint assessment of the questions that arise and record their findings are suitable for thispurpose. The decision as to whether a US company's cloud services should be used for the first time or continue to be used lies solely with the respective organisation. In particular, it should not be made by the data protection authorities, who will naturally always issue warnings. Public bodies that have done their homework properly and consider the risks to be bearable and accept them in good faith should not be intimidated by this and should have the courage to implement their plans accordingly.

|

FLARA Light - quicker assessment of standard cases Most people are familiar with the classic method of assessing the probability of a foreign authority access, which is typically carried out jointly in a workshop. For some projects, however, this is overkill. For these cases, we have developed a "light" version that can be carried out in just five minutes by answering eight questions. These eight questions define the typical drivers for calculating the probability of occurrence and are therefore intended for standard situations. The FLARA Light can be licensed from us. It is also part of the CCRA FI Light (see below). |

|

CCRA - for a diligent examination of cloud projects Originally developed for Swiss banks, the Excel-based "Cloud Compliance and Risk Assessment" (CCRA) tool is used to systematically assess and document larger or more significant cloud projects in terms of their legal compliance and overall risks. The "CCRA-FI" version for regulated financial institutions covers the requirements of the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), while the "CCRA-PS" version for public institutions and hospitals covers the requirements for public institutions in Switzerland. We offer CCRA-FI under licence; there is also a light version for less sensitive projects, which can be completed much more quickly and still allows a serious compliance and risk assessment. The tool is now being used successfully by numerous Swiss banks, as audits also show. More and more providers are also using it to demonstrate their cloud compliance. CCRA-PS is in turn freely available as open source for the public sector including hospitals (here). This, too, has been and is being used by public authorities in over a dozen cantons and by the federal authorities to diligently review and document cloud projects. The Federal Data Protection and Information Commissioner (FDPIC) stated in December 2024: "The FDPIC considers https://vischerlnk.com/ccra-ps to be suitable for documenting and analysing risks when examining cloud and other projects." We are happy to provide support in the assessment of cloud projects. |

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.