This decision concerns the simulation of weldments. However, the simulation was considered non-technical by the EPO, specifically in light of the decision G1/19 of the Enlared Board of Appeal. Here are the practical takeaways from the decision T 2594/ 17 () of May 20, 2021 of Technical Board of Appeal 3.4.03:

Key takeaways

This is one of the first decisions referring to the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19 regarding computer-implemented simulations.

For the purposes of assessing inventive step of a computer-implemented simulation, it is not a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, in whole or in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process.

The invention

The subject-matter of the European patent application underlying the present decision was summarized by the Board in charge as follows:

2. The claimed invention

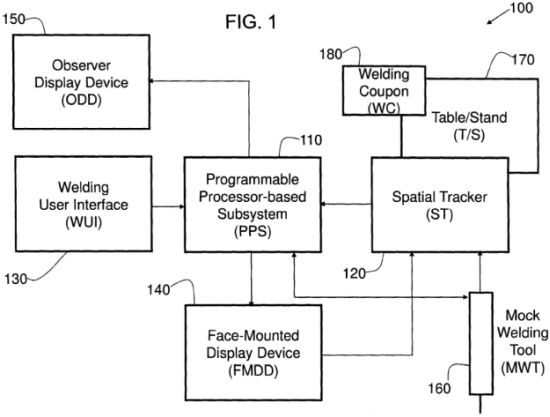

The claimed invention relates to a system and a method for carrying out virtual (computer-simulated) testing and inspection of virtual (computer-simulated) weldments.

The claimed system renders 3D images of virtual weldments. The virtual weldments are generated using a virtual reality arc welding system, which is described in detail in the application.

The system carries out a series of computer-simulated tests on the rendered virtual weldments. These computer simulated tests correspond to tests carried out in "real-life" weldments in order to assess their quality and identify possible defects. The system renders animations of such tests and displays the virtual weldment after the test. The user can then inspect the tested virtual weldment by moving the image around in a display.

The system is conceived for a training context in which trainees generate virtual weldments, which are then tested and the result of the test can be used as criterion for passing or failing an examination.

Fig. 2 of WO 2012/137060 A1

Here is how the invention was defined in claim 1:

Claim 1 (main request)

A system (100) for the virtual testing and inspecting of a virtual weldment, said system (100) comprising:

a programmable processor-based subsystem (110) operable to execute coded instructions, said coded instructions including:

a rendering engine configured to render at least one of a three-dimensional (3D) virtual weldment (2200) before simulated testing, a 3D animation of a virtual weldment (2200) under simulated testing, and a 3D virtual weldment (2200) after simulated testing, and

an analysis engine configured to perform simulated testing of a 3D virtual weldment (2200), and further configured to perform inspection of at least one of a 3D virtual weldment (2200) before simulated testing, a 3D animation of a virtual weldment (2200) under simulated testing, and a 3D virtual weldment (2200) after simulated testing for at least one of pass/fail conditions and defect/discontinuity characteristics;

at least one display device (140, 150) operatively connected to said programmable processor-based subsystem (110) for displaying at least one of a 3D virtual weldment (2200) before simulated testing, a 3D animation of a virtual weldment (2200) under simulated testing, and a 3D virtual weldment (2200) after simulated testing; and

a user interface (130) operatively connected to said programmable processor-based subsystem (110) and configured for at least manipulating an orientation of at least one of a 3D virtual weldment (2200) before simulated testing, a 3D animation of a virtual weldment (2200) under simulated testing, and a 3D virtual weldment (2200) after simulated testing on said at least one display device (140, 150),

wherein said simulated testing includes at least one of simulated destructive testing and simulated non-destructive testing of the virtual weldment.

Is it patentable?

The Board in charge considered the claimed system to be a general purpose personal computer configured to execute virtual testing and inspection of virtual weldments. Hence, a common computer was considered as a suitable starting point for the assessment of inventive step:

3.1.3 The board concludes from the above that the claimed system is a general purpose personal computer configured to execute virtual testing and inspection of virtual weldments.

3.1.4 The board considers thus a notoriously well-known, general purpose, personal computer to be a suitable starting point for the skilled person.

On the differences over the closest prior art and on the underlying technical problem, the Board commented as follows:

3.2 Differences and technical problem

3.2.1 Compared to such a notoriously well-known personal computer, the claimed system differs in that it can ("is operable to") execute coded instructions including a rendering engine configured to render a 3D virtual weldment and an analysis engine configured to perform simulated testing and inspection of the 3D virtual weldment for pass/fail conditions and/or defect/discontinuity characteristics. In addition, the display device can display the 3D images of the weldment and the user interface allows the user to move the displayed images around ("manipulating an orientation").

In essence, the claimed system renders a 3D image, which can also be an animated 3D image (of a virtual weldment) and processes this image by simulating testing and inspection of the virtual 3D weldment. It then displays the processed image and allows the user to move it around.

Importantly, the Board in charge stated that the claimed subject-matter (as well as the application as a whole) only refers to the testing of virtual weldments and not to "real life" weldments:

3.2.2 As a first point the board notes that the claimed system carries out computer-simulated testing and inspection of a virtual weldment, i.e. of a computer-simulated weldment and not of a physical, i.e. "real life", weldment.

3.2.3 Moreover, the claimed system does not simulate such tests carried out on a "real life" weldment. In other words, there is no particular "real life" weldment that needs to be tested (and inspected) and instead of carrying out "real life" tests on it, computer-simulated tests are carried out on a computer-simulated virtual representation of that particular "real life" weldment. As the application describes, only a virtual weldment is generated, mainly for training purposes, and without any link to a particular "real life" weldment.

As such, the the claimed system would only refer to image processing which is a non-technical task as conformed by a plurality of decisions of the EPO's Boards of Appeal:

3.2.5 In the board's opinion, therefore, the claimed system carries out image processing. Images of weldments are rendered, manipulated and displayed. That the images represent weldments or that the manipulations represent testing and/or inspection of those weldments is, in the general manner claimed and described in the application, the result of the cognitive content (information) of the displayed images. It is the user who perceives the images as weldments and the manipulation of those images as testing and/or inspection. Such cognitive information ("what" is displayed) is not related to any technical problem or technical constraints. This applies also to the type of tests (e.g. destructive or non-destructive) the system is able to simulate.

It is established case law that the cognitive content of a displayed image ("what" is displayed) is in principle not a technical feature (Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the EPO, 9th Edition, July 2019, I.A.2.6).

Against these finding, the appellant argued inter alia as follows:

Making reference to paragraph [0043] of the application, the appellant pointed out that simulated weldments generated using the VRAW system could be used beyond training. Such a simulated weldment could be integrated in a simulated bridge and the testing could involve simulations of the bridge over time in order to estimate whether the quality of the weldment would influence the life time of the bridge. In analogy to the reasoning of the decision T 625/11, where the deciding board had concluded that a simulation of a nuclear reactor was technical, the features relating to the simulation of the testing of the weldment were also to be seen as technical.

However, according to the Board in charge, the appellant's arguments would not be in line with the decision G1/19 of the Enlarged Board of Appeal:

3.2.10 Secondly, regarding the technical character of the simulation, the board notes that the decision referred to by the appellant was cited in decision G1/19 of the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBoA)(see point 109 of the reasons), which relates to computer-implemented simulations. In G1/19 the EBoA concluded that, for the purposes of assessing inventive step of a computer-implemented simulation, it is not a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, in whole or in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process (see e.g. points 1 and 2 of the Headnote).

Hence, even if the computer-simulated testing of the virtual weldment were to be carried out within a computer-simulated simulation of a bridge (the bridge having incontestably sufficient technical character), this would not have any influence on the board's assessment of inventive step of the features of the claimed invention. Moreover, the board points out that in the system of claim 1 of the Main Request there is no mention of nor any suggestion to such a type of testing at all but only of testing used for training purposes, as the reference to the determination of a pass/fail condition indicates.

Hence, the Board considered the distinguishing features as not technical:

3.2.11 Summarising, the claimed system differs from a notoriously well-known general purpose computer in that it is configured to display images of virtual weldments, of virtual testing of those virtual weldments, and of the results of the virtual testing on those virtual weldments. It can also determine a pass/fail condition based on those results.

These differences relate only to the cognitive content of the images and the board does not consider them to be technical features (see point 3.2.5 above).

As a result, the Board ignored the distinguishing features for assessing inventive step and thus considered the claimed subject-matter to be rendered-obvious. Hence, the appeal was dismissed.

More information

You can read the whole decision here: T 2594/ 17 () of May 20, 2021

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.