- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

- in United States

- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

The Local Division of Düsseldorf is the first UPC panel to set out the prerequisites and establish essential factors for assessing infringement of second medical use claims in the UPC system. Its approach builds on the criteria developed by national (German) courts.

1.Background and facts of the case

Sanofi and Regeneron assert EP3536712(hereinafter, "patent-in-suit") against Amgen.

Claim1 of the patent-in-suit concerns a pharmaceutical composition comprising an antibody (briefly referred to as "PCSK9 inhibitor", hereinbelow) for reducing lipoprotein(a) (briefly, "Lp(a)").

Lipoproteins ("lipo" is ancient Greek for fat) transport fats in the blood. The human body's own lipoproteins include, among many others, LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and Lp(a). Both lipid blood parameters, LDL-C and Lp(a), were known to be independent risk factors for atherosclerosis and related cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke and myocardial infarction.

Claim1 of the patent-in-suit is in the format of a second medical use claim, namely administering PCSK9 inhibitors for use in reducing Lp(a). The first medical use is administering PCSK9 inhibitor to treat or prevent hypercholesterolemia or an atherosclerotic disease related to elevated LDL-C. In other words, it was known in the prior art that PCSK9 inhibitors were useful for reducing LDL-C and reducing the risk of CVD caused by elevated LDL-C.

Sanofi and Regeneron sued Amgen for the alleged infringement of the patent-in-suit by Amgen's medicinal product distributed under the name Repatha® (evolocumab). Repatha® is an antibody directed against PCSK9 ("PCSK9 inhibitor") that is authorized for the treatment of, inter alia, so-called hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia, i.e., the reduction of cardiovascular risk in patients with elevated LDL-C. Neither Repatha® nor Praluent® (alirocumab), Sanofi and Regeneron's PCSK9 inhibitor drug, is authorized for lowering Lp(a) levels or for lowering cardiovascular risk by lowering Lp(a) levels.

Sanofi and Regeneron alleged that Amgen infringed said second medical use claims because the SmPC of Repatha® in section5.1, concerning pharmacodynamic properties, contains clinical trial data on the effects of Repatha® on, inter alia and in particular, Lp(a), which, in turn, allegedly induces doctors to prescribe Repatha® for lowering Lp(a) in accordance with the patent, even when they target LDL-C. Amgen responded by, inter alia, showing that the mere mention of the clinical trial data concerning Lp(a) lowering in section 5.1 of the SmPC did not induce doctors to prescribe Repatha® for the claimed second medical use.

Amgen filed a counterclaim for revocation against the patent-in-suit and attacked the validity of the patent-in-suit based on, inter alia,the argument that PCSK9 inhibitors always lower Lp(a), which effect was already known to the person skilled in the art at the priority date of the patent-in-suit.

Sanofi and Regeneron defended the validity of the patent-in-suit against Amgen's counterclaim for revocation by arguing, inter alia, that the subject-matter of the patent-in-suit was novel as the lowering of Lp(a) levels was a new clinically relevant therapeutic effect of PCSK9 inhibitors that defined a new clinical situation.

2. The ruling of the UPC Local Division of Düsseldorf

The UPC Local Division of Düsseldorf ruled that Amgen does not infringe the patent-in-suit and for the first time in the history of the UPC system ruled on the requirements for the finding of infringement of second medical use claims.

The Court held that for a finding of infringement of second medical use claims, the claimant must show that the attacked embodiment is offered or placed on the market in such a way that it is used or may be used according to the patent, and that the alleged infringer knows or should have known of such use.

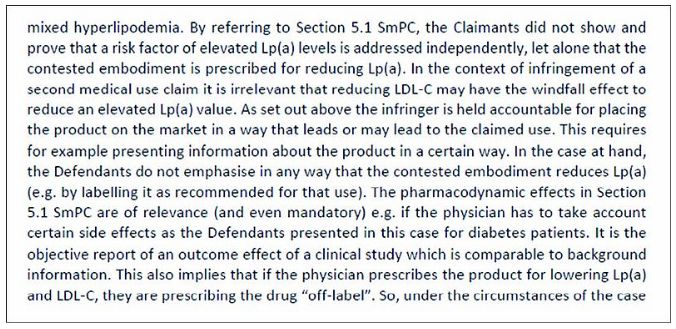

In the present case, the Court found that the information on pharmacodynamic effects provided in section5.1 of the SmPC for Repatha® is not suitable for showing that Amgen places the product on the market in an infringement-relevant manner (see mn. 191 of the decision).

(mn. 191 of the decision)

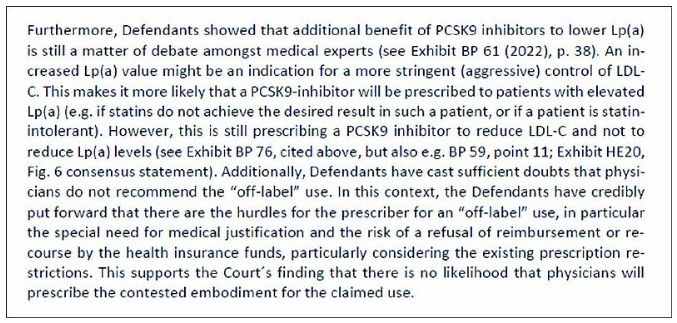

Furthermore, Sanofi and Regeneron failed to demonstrate that prescriptions of Repatha® for the claimed use have already been made or that there is a substantial likelihood that such ("off-label") prescriptions will be made (see mn. 192 et seqq. of the decision).

(mn. 198 of the decision)

Finally, Sanofi and Regeneron were not able to show that Amgen was aware or at least should have been aware that Repatha® was used to lower Lp(a) levels. (see mn. 199 of the decision).

3.Comments and remarks

The present decision of the Local Division of Düsseldorf is a landmark decision setting forth, for the first time, requirements and factors for the assessment of infringement of second medical use claims. This is all the more helpful, as case law in the member states is scarce.

a. National German practice

Art. 54 (5) EPC and, in Germany, Sec. 3 (4) German Patent Act provide that a patent can be granted for a medical use of a substance, even if the substance was already known in the prior art, provided that the invention teaches a new and inventive specific application over the previously known use of said substance.

According to German case law, in case of second medical use patents, the protective effect of the patent extends to acts preceding the actually infringing use, namely acts with which the product is prepared for the protected use. Accordingly, second medical use patents also prohibit offering, distributing, using etc. the protected product for the patented purpose, i.e., the second medical use (see Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf, GRUR 2017, 1107 – Östrogenblocker, one of the German landmark decisions on infringement of second medical use claims).

German case law distinguishes between two liability concepts: (i) liability based on so-called manifest preparation ("sinnfällige Herrichtung" in German), and (ii) liability without manifest preparation ("herrichtungsfreie Haftung" in German).

(i) Liability based on manifest preparation presupposes that the product is meaningfully prepared for the specific patented use prior to its distribution, so that the protected therapeutic use is foreseeable.

(ii) Liability without manifest preparation requires that the product is suitable for the patented purpose and is actually used, not merely sporadically but to a relevant extent, in accordance with the patent, and that the distributor knows or at least should know of such use practices and takes advantage thereof (i.e., by not taking suitable measures to prevent such use).

In practice, these liability concepts are often applied in cases of certain off- label uses. These are characterized by the fact that a drug (e.g., a generic drug) is only marketed for a patent-free indication but is actually used to a significant extent for the patent-protected indication of the reference drug.

b.UPC examination approach

According to the Düsseldorf Local Division, the claimant must show and prove (i) as an objective element, that there is either a prescription for use according to the patent or at least additional circumstances showing that such use may be expected to occur, and (ii) as a subjective element, that the infringer knows or reasonably should have known of such use (see mn. 182 of the decision).

Relevant aspects that may be considered when assessing (the expectation of) a patented use and the alleged infringer knowing thereof include (see mn. 183 of the decision):

- The extent or significance of the allegedly infringing use;

- The relevant market, including what is customary on that market;

- The market shares of the claimed use compared to other uses;

- What actions the alleged infringer has taken to influence the respective market, either positively de facto encouraging the patented use or negatively by taking measures to prevent the product from being used for the patented use.

c.Conclusions

The Düsseldorf Local Division, which was comprised of two renowned and experienced German judges – Mr Thomas and Dr Thom – joined by two foreign judges – Mr Kupecz and Mr Dorland-Galliot, does not simply transfer known and established German – or other countries' – examination standards but develops its own approach for assessing infringement of a second medical use claim.

Unlike in German case law, the UPC's approach does not expressly distinguish between liability based on manifest preparation and liability without manifest preparation but applies a multi-factor analysis, which nevertheless seems to be inspired by the German approach.

In the present case, Claimants failed to show (i) that the information provided in section 5.1 of the SmPC of Repatha® induced physicians to prescribe the product ("off-label") in an infringing manner and (ii) that ("off-label") prescriptions, i.e., a prescription practice, of Repatha® have already been made or are at least foreseeable and (iii) that Amgen was aware or reasonably should have been aware of such use.

Under the present set of circumstances, liability would also have to be denied under the German principles as there would neither be a manifest preparation nor an established prescription practice.

What claimants can take away from the present decision is that

in view of the frontloaded character of UPC proceedings, sufficient

evidence must be submitted for the relevant existing or imminent

use, i.e., prescription practice of the attacked product

in accordance with the patented second medical use claim early in

the proceedings (see mn. 200 et seq. of the decision). Therefore,

the thorough preparation of the complaint is even more important

when claiming infringement of a second medical use claim.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.