Quick Take

- Financial services firms and markets generally will be sensitive to potential coalition partners and their policy stance on investment and debt both domestically but also at the EU level.

- A number of possible coalitions could be formed. Doing so will take and at present the grand coalition of SPD (clear winner in the 2021 election) and the CDU/CSU is unlikely to survive.

- The FDP (yellow) may be courted by the SPD (red) and the Greens to join a so-called "Traffic Light" coalition which could yield a controlling majority (416 seats of the 386 needed). Equally, a coalition amongst CDU/CSU (Black), Greens and FDP would provide 406 seats. FDP's Lindner has set his claim to the German Federal Finance Ministry as a precondition to joining any coalition.

- The Greens manifesto foresees an additional spending of EUR 50 bn per year for this decade for public infrastructure investments. The CDU/CSU and FDP however argue that the EU's NextGeneration EU fund (the EU's main COVID-19 recovery vehicle) as well as the EU's issuance of common debt should be a one-off effort.

- Brexit remains an issued for the interim or new German government as the UK is waiting for the EU to respond to its "Command Paper" from July 2021 in which it sets a long list of demands to renegotiate the Northern Ireland Protocol.

- Closer to home, the German government is expected to provide political steer to iron out reforms to the EU's Stability and Growth Pact i.e., the fiscal rulebook, which is set to come back into force in 2023, as well as how to settle the rule of law disputes with Hungary and Poland.

For now, all eyes are tilted to Berlin to see how the coalition construction challenge will play out and what makes it into any coalition agreement. Attention will also turn towards who will take the Chancellery and key ministries and thus who will continue to provide the focus and agency that Germany under Merkel has brought to Europe. The Bundestag is set to head back to work on or around 20 October 2021 and key announcements are likely to be made in a successive fashion from then to the end of the year. Chief amongst them will be the caretaker government preparing the 2022 budget with a likelihood of no fiscal tightening beyond the termination of pandemic support measures.

Background

Germany has voted... now the challenge looms as to who will be able to form a coalition and more importantly with whom as parties try to seize the Chancellorship. The Bundestag elects the Chancellor and since 1949 these have always been either from the CDU or SPD. The threshold to control stands at 368 Bundestag seats (i.e., 50%) and any party can try (any number of times) to form a coalition and indeed the Bundestag has a history of running on two party coalitions (of a big and a smaller party). Under Merkel, the grand coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD became the new normal. Once a coalition is in place, work goes into a coalition agreement codifying the most important goals and objectives of the cabinet. Largely this involves a skillful balancing of various party's election manifestos.

The CDU/CSU plus SPD "grand coalition" is unlikely to succeed and any Chancellor will have to step in some large shoes left by the outgoing administration's legacy of domestic, European and global leadership under a record four terms of a German government taking a global lead in challenging controversy, crisis and COVID. After 16 years at the helm, Chancellor Merkel, while standing down on her own terms, may remain in charge as caretaker for the next weeks if not months as protracted coalition talks progress. What Merkel might do next is not clear, with many suggesting she might at some point go to Brussels if the relaxation offered by retirement provides to be too monotonous for "Mutti" (literally a short form for mother but used as a term of endearment for Chancellor Merkel).

The results in detail and the coalitions that could follow

The 2021 federal election for the Deutscher Bundestag marks the first election of the post-Merkel era and the worst electoral result for the CDU/CSU (blame may be more to the candidate than Merkel) with historical gains for the Greens, especially amongst younger voters who also moved away from Germany's traditional parties to the FDP. The SPD won just 14% and the CDU/CSU just 11% from the under 25s. Many of those voters may be too young to remember politics before Merkel.

Due to COVID-19 postal voting increased considerably and voter turnout in total, according to the provisional official results) amounted to 76.6%. The 2021 election also marks Germany's largest ever Bundestag, with 735 seats up from 702 in the previous cycle distributed as follows:

- 206 seats to the pro-European social democratic center-left Socialist Party of Germany (the SPD) led by Chancellor Candidate Olaf Scholz – Germany's incumbent Finance Minister while being the candidate for continuity, has been in the spotlight for a number of shortcomings at supervisory authorities reporting to him. Nevertheless, it is expected that Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the current German Federal President since March 2017, member of the SPD and former Foreign Minister (2005 to 2009 and 2013 to 2017) and Vice-Chancellor (2007 to 2009) will ask Scholz to take the first attempt at forming a coalition.

- 196 seats to the pro-European liberal conservative center to center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party, the center right Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), led by Armin Laschet, current Minister President of North Rhine Westphalia, Germany's most populated Federal State. Armin Laschet, Merkel's chosen successor seemed to stumble at every turn, even when casting his own vote at the ballot, and it was too late to switch to Markus Söder, the more accomplished CSU leader, however he is more rooted in the Free State of Bavaria then in the rest of the Federal Republic and may choose to run in 2025. A grand coalition between CDU/CSU and SPD in the 2021 elections would have 402 seats and thus a controlling majority. However, neither the SPD nor the CDU/CSU currently support a bid for a grand coalition and it is conceivable that the CDU/CSU will go into the opposition and a new leadership contest to replace Armin Laschet may follow. Lastly, while there is some precedence in recent German electoral history for the number two party (i.e., the CDU/CSU) to form the government the loss of votes and Laschet's low ratings in the polls show little prospect of that happening.

- 118 seats to the center left Alliance90/Greens (the Greens) led by Annalena Baerbock, having won 14.8% of the vote. During the Summer of 2021 they were projected to win in excess of 20%. Gaffes followed and numbers have dropped. The Greens however do hold seats in fourteen of sixteen State Legislatures and 21 MEPs in the European Parliament as well as its position as the founding and largest member of the European Green Party and the Greens-European Free Alliance Group in the European Parliament. In addition to their green, environmental and anti-nuclear politics, the party is strongly proEuropean advocating European federalism The Greens have successfully formed a coalition in the Bundestag in 1998 and 2002 as a junior partner to the SPD. In 2021 such a renewed Red-Green coalition would only secure 324 seats and thus fall short of the 368 seats needed. Given the Greens' number of won seats, it is very conceivable that they will be represented in the next coalition government regardless of who they partner with.

- 92 seats to the center to center right liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) led by Christian Lindner, who has led the FDP as an opposition party since the 2013 federal elections in which the FDP failed to clear the 5% hurdle to enter the Bundestag for the first time since 1949. Lindner is known as a fiscal hawk, having publicly criticized outgoing Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble for not being tough enough on Greece and not cutting income taxes for middle-class workers. The FDP may be courted by the SPD and the Greens to form a coalition which could yield 416 seats of 386 needed. Equally, a so-called "Jamaica coalition" (given the colors of the parties) amongst CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP would provide 406 seats. Lindner has set his claim to the German Federal Finance Ministry as a precondition to joining any coalition. Linder in 2017 due to differences in fiscal policy walked out of talks when Merkel last attempted to form a Jamaica coalition with her party settling on a grand coalition with the SPD. An attempt to form a "Deutschland coalition" given the colors of CDU/CSU (black), SPD (red) and FDP (yellow) would secure 494 seats but would bring deadlock due to long-standing ideological differences between the parties.

- 83 seats to the German nationalist right-wing Eurosceptic populist party the Alternative for Germany (AfD). In the 2017 Bundestag election the AfD entered the parliament for the first time, winning 94 seats and becoming Germany's third-largest party and the single largest opposition to the coalition government. While the AfD has lost support overall it remains the second-strongest party in the eastern states.

- 39 seats to the democratic socialist Left Party (Linke), which was formed out of a merger of the three left parties, including the PDS, the direct descendent of the ruling party of East Germany, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). The Linke is represented in ten of Germany's sixteen state legislatures including all five of the eastern states and will likely in this current legislative cycle of the Bundestag form an opposition party. While Scholz had previously not ruled out an SPD, Linke and Greens coalition, numerically and to the relief of business this scenario falls five short of a 368 majority.

- 1 seat to the centrist South Schleswig Voters' Association (SWW) a regional party in the northern Federal State of Schleswig-Holstein representing Danish and Frisian minorities of the State that has returned to the Bundestag for the first time since 1961. Traditionally, the SWW aligns itself with the SPD.

At the Federal State level, it is important to note that two regional elections in Berlin and MecklenburgVorpommern saw the SPD retain its leading position and the AFD lose ground. The heads of the 16 Federal States, who wield significant power in German politics, therefore remain evenly split, seven from the SPD, seven from the CDU/CSU, one from the Greens and one from the Linke.

Next steps for a coalition – balancing the electoral manifestos

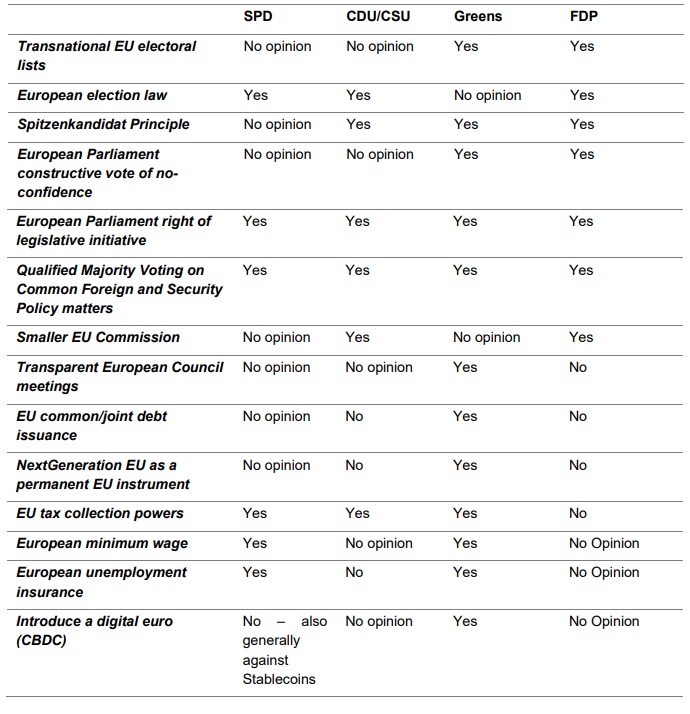

The parties in the Bundestag have in addition to domestic policy proposals a number of differing stances on key EU policy issues. The current CDU/CSU and SPD grand coalition in 2017 had a rather ambitious EU chapter in their coalition agreement yet few concrete proposals have been implemented. The 2021 election manifestos lacked a clear view and path on future EU integration. In contrast the EU and the FDP both have a strongly pro-integration and federalist vision for the EU's future. The Greens want to use the forthcoming Conference on the Future of Europe as a path to a Federal European Republic and the FDP's proposal is for a decentralized federal European state as a desired goal. Unsurprisingly, the Linke and AfD are explicit in their criticism of the EU with the AfD advocating Germany ceasing to be a member altogether, abandoning the euro and so on. In summary this can be visualized as follows:

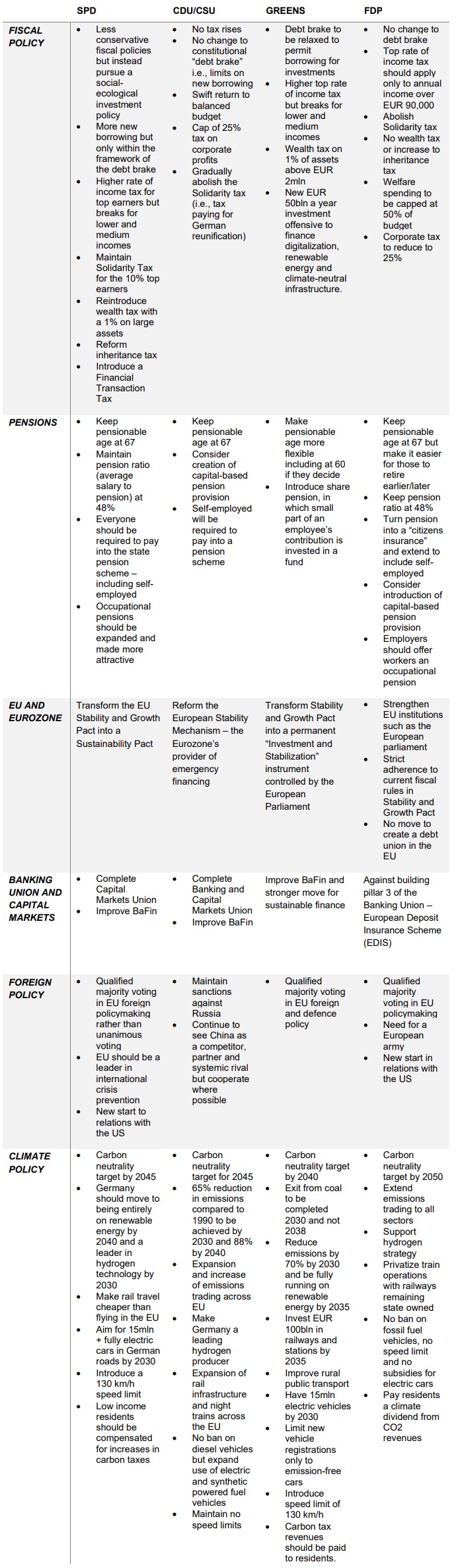

Turning back to domestic policies, the real problem in building a coalition will be how to align the positions of the Greens and the FDP in respect of Germany. The FDP wants to cut red tape and used market-based efforts to combat climate change while the Greens are fundamentally opposed. On tax, all parties disagree. The FDP wants to cut taxes and the Greens and the SPD want to raise them.

At a high level here are some of the positions from the leading parties with a shot at building a coalition.

Implications for financial services firms

The overall policy stance of the next coalition government will be more left leaning and put a clear emphasis on the environment when compared to the Merkel Cabinets. The FDP has laid claim to the Finance Ministry and the Greens have set their sights on the Environment Ministry, possibly Foreign Ministry and equally the office of Vice Chancellor. The new coalition government will remain staunchly pro-European and support the European Commission's efforts on sustainability and digital transformation as well as President Ursula von der Leyen's more social democratic policies.

The incoming government inherits a high structural deficit and the scope for investments and spending, without tax increases, will be limited. In a post-COVID-19 environment tax increases are expected to remain moderate although the SPD have pushed for higher rate income tax to increase. It is also conceivable that the new government will leverage public funding in the form of guarantees to attract supplementary private investors.

While the FDP is unlikely to shift policy on the EU's reform of the Stability and Growth Pact, the SPD has been very supportive of financial services and promoting Frankfurt as a financial center. Regulatory and institutional reforms in Germany are likely to continue both in a bid to strengthen BaFin but also to clean up and modernize markets and business practices.

All parties are also looking at how to reset relationships with the U.S. and its new administration. The EU's push for a US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC), which meets for the first time in Pittsburgh on 29 September, provides a good avenue to do just that. The TTC will have 10 working groups focusing on technology standards, green technology, supply-chain security, data governance, export controls, investment screening and global trade issues amongst other matters that are of interest to EU and indeed German business.

One thing that is however certain is that whatever coalition does succeed, the German financial services regulator, the BaFin will continue to see support for institutional reform. The same is also likely to be the case for Germany continuing to push both Banking Union and Capital Markets Union as well as supporting the EU's Green Deal, all of which are catalysts for deepening the EU's Single Market and embedding sustainability across the EU.

The German elections and the impact on the EU presidency and other elections

What is certain though is that the longer the coalition talks take in Germany, the greater the headache for France and its assuming the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU in early 2022 for six months. France is heading into its own elections in April 2022 and Emmanuel Macron has only a has a small window to shape EU policies and the direction of European integration while preparing for a difficult domestic election campaign. In the worst case both Germany and France might be political lame ducks at the start of 2022. Looking more broadly at the 2022 and 2023 electoral calendar, a host of EU Member States will be going to the polls in regional, national and presidential elections.

It remains to be seen whether Germany's new government can build on the best of Merkelism deepen the trust built across national capitals in the EU and further afield at a time when the EU faces internal challenges such as a weaking of the rule of law through to external challenges of needing to pursue strategic autonomy.

Originally Published September 2021

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.