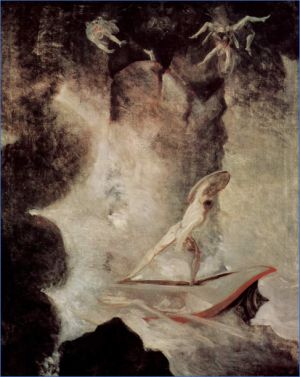

Attribution: Odysseus, Scylla - Johann Heinrich Füssli

(1794-96)

In Homer's Odyssey, the wayward hero Odysseus is travelling by ship when beset by two threats within an arrow's distance from one another: on one side is Scylla, a beast with many heads, and on the other side is Charybdis, a deadly whirlpool.1

This is an apt metaphor for what faces litigants trying to navigate the choppy waters of transnational discovery; nowhere is this more true than with managing jurisdictional discovery under both US and Chinese legal systems.

Foreign Defendants and Personal Jurisdiction

Since the US Supreme Court's decision in International Shoe Co. v. Washington,2 Courts have come to recognize two types of personal jurisdiction: "general" jurisdiction and "specific" jurisdiction.3 This distinction can be attributed to Professors Arthur T. von Mehren and Donald T. Trautman, who authored a paper on the subject in 1966.4

With general jurisdiction, Courts rely on the "essentially at home" test. In other words the defendant's contacts with the forum must be "so continuous and systematic as to render them essentially at home in the forum state."5 As it relates to foreign defendants, general jurisdiction was limited by the US Supreme Court ruling in Daimler and today plays a reduced role.6

Chinese defendants without a domicile in the US will typically be haled into US Courts through the use of "specific" jurisdiction. Unfortunately, this most often involves the infamous minimum contacts test. A minimum contacts enquiry involves two prongs. First, the "purposeful availment" prong, which asks whether the litigant intentionally directed their activities in the forum state.7 Second, the "relatedness" prong, which asks whether the lawsuit results from injuries that are related to (or arise out of) activities in the forum state.8 Nevertheless, defendants may defeat a finding of specific jurisdiction, even after meeting the minimum contacts test, if doing so is considered unreasonable in that it contradicts notions of "fair play" and "substantial justice".9

The minimum contacts test is notorious because its elements (especially relatedness) have been described, by some, as nebulous at best:10

There is little in the way of clear standards for what makes a contact with the forum 'related to' the litigation or qualifies a dispute as 'arising out of the defendant's contacts with the forum.'

Indeed, there is more agreement among the Courts about what specific jurisdiction is not rather than what it is. While guidance from the US Supreme Court does suggest that specific jurisdiction is distinctive, in that it is "case-linked", it stops short of clarifying thornier issues involved with the concept.11

The Role of Personal Jurisdiction - Taishan Drywall

In some cases, disagreements over personal jurisdiction can lead to a decade of litigation.

In the past, Chinese defendants in the US market could "have the best of both worlds." It was common practice to access the US market while avoiding liability for breaching local laws. In the words of Peking University Professor Ray Campbell:12

Historically, with U.S. judgments not recognized in China, many Chinese defendants had the best of both worlds-they were free to sell into the U.S. market, but protected from after-the-fact regulation [in the form of litigation] should the products prove defective.

This changed drastically with a seminal class action involving a Chinese defendant. ("Taishan Drywall").13 A Chinese company, Taishan Gypsum Co., was not only held in default for failing to appear in a Louisiana Court to defend a claim (liability for defective drywall), but was further barred from the US market by presiding Judge Fallon. This was especially significant considering that the next most significant case fought over personal jurisdiction against a Chinese defendant at the time, Gucci Am., Inc v Weixing Li ("Gucci I" from Gucci "I", "II", and "III", the "Gucci Trio"), resulted in contempt for failure to comply with an asset freeze,14 not denial of market access.

Challenging this default judgment, Taishan argued that it must be void on the grounds that this and other US Courts lacked personal jurisdiction.

And so began, in October 2010, a jurisdictional discovery battle between Taishan and the plaintiffs. The former were required to prove that Taishan had sufficient "minimum contacts" with forum states to allow US Courts to exercise personal jurisdiction.

As a result of this battle, Taishan had to submit to the US plaintiffs' discovery requests. These included three depositions in Hong Kong which degenerated into "chaos and old night" (as described by Judge Fallon), and which were ultimately in vain after being found ineffectual (due to disagreements among interpreters, counsel, and witnesses, among other issues). It also included production of both written and electronic documents, and a second, more "hands-on" deposition in Hong Kong where the Court appointed a Federal Rule of Evidence 706 expert to operate as the sole interpreter at the depositions. The Court also decided to travel to Hong Kong itself to preside over the depositions, allowing it to rule immediately on objections and avoiding many problems present during the first deposition.

Upon conclusion of this lengthy transnational process, the Louisiana Court found in favour of the plaintiffs. The Court held that Taishan, indeed, had the minimum contacts necessary to exercise personal jurisdiction. In 2014, the 5th Circuit upheld this ruling in two judgments.15 Adding another wrinkle to the case, following the U.S. Supreme Court case of Bristol-Myers Squibb v. Superior Court of California,16 Taishan again challenged the Court's personal jurisdiction and filed a motion to dismiss in 2017.17 This challenge, too, was in vain.

Finally, after a decade of litigation, the parties reached a settlement agreement. Under this agreement, finally approved on January 10, 2020, Taishan agreed to pay $248 million to settle the claims of most plaintiffs.18 In US Courts, as evidenced by this hard-fought and lengthy litigation process, personal jurisdiction is a critical factor in determining whether or not a plaintiff will succeed in claiming against a foreign entity.

Jurisdictional Discovery: Hague Convention or FRCP

In conducting jurisdictional discovery to establish personal jurisdiction against a foreign defendant, an important consideration is whether the plaintiff should follow the procedures set out in the Convention on Taking Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters ("Hague Evidence Convention") or the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ("FRCP").

Despite being signatories, many countries imposed reservations at the time of their accession to the Hague Evidence Convention. China's reservations are extensive,19 making the Hague Evidence Convention a method that is tardy and inapplicable to most discoveries.20 It is not a popular option. According to correspondence between Professor Campbell and the Chinese Ministry of Justice ("MOJ"), only about 40 requests are received - cumulatively from countries around the world - by the MOJ each year.21 Nevertheless, the Hague Evidence Convention was designed not as a ceiling, but as a floor (Art. 27), and many Courts prefer to forego its processes in favour of other methods.

Much more popular is the FRCP, granting US plaintiffs speedier timelines and more familiar processes. Generally US Courts are willing to allow discovery under the FRCP, though further to the decision in Aerospatiale these must be case-by-case determinations.22 Accordingly, Courts must balance the importance of the information sought, sovereign interests, and the likelihood that the Hague Evidence Convention will be effective in determining whether to grant discovery under the FRCP. While not automatic, the chances are that the FRCP will apply for obtaining foreign evidence against Chinese litigants. The District Court in Gucci v Weixing ruled that the "Hague Convention is of limited utility in China in large part because its implementation remains uncertain and unpredictable."23 Of course, one condition of relying on the FRCP is that the Court have personal jurisdiction over the defendant, or reason to conduct discovery into personal jurisdiction. When personal jurisdiction has yet to be established, as is the case with jurisdictional discovery attempts, failure to satisfy the latter condition (reason to conduct discovery into personal jurisdiction) can lead to a catch-22.24

It is noteworthy that Chinese defendants are increasingly choosing to avail themselves of their rights before US Courts. Large default cases like Taishan Drywall are now rare, and Chinese companies today are much savvier than before in navigating the US legal system.

A Rock and a Hard Place: Narrowing US Jurisdictional Discovery Requests

Invoking conflict with Chinese laws is a common way for Chinese defendants to seek to narrow the scope of US jurisdictional discovery requests. These include, most commonly, Articles 2 and 32 of the Law of the People's Republic of China on Guarding State Secrets, under which state secrets are broadly defined to include trade secrets.25 Divulging state secrets to a foreign entity in violation of this law can result in criminal consequences under Article 111 of the Criminal Code of China, and as such can sometimes narrow an overbroad discovery request when invoked before a US Court. An emerging trend is to also invoke conflict with Chinese data privacy laws, engaging numerous data control and privacy concerns. The latest such blocking statute, the Data Security Law which came into effect September 1st, 2021, imposes fines for unauthorized compliance with overseas judicial orders.26 This is significant because in a digital word, discovery increasingly means ediscovery.

In seeking to limit US discovery requests though, it is important to set realistic expectations, because overreaching risks reducing the defendant's chances of success. US Courts have repeatedly ordered foreign banks to produce documents in violation of their home country laws. They are generally unwilling to consider fear of punishment under foreign laws when deciding whether to subject offshore documents to US discovery. The reason? To do so would encourage parties to hold such documents offshore and risk undermining US discovery. In a canonical US Supreme Court ruling on the subject, Société Internationale Pour Participations Industrielles et Commerciales v. Rogers, the Court stated:27

[T]o hold broadly that petitioner's failure to produce [...] records because of fear of punishment under the laws of its sovereign precludes a court from finding that petitioner had "control" over them, and thereby from ordering their production, would undermine congressional policies [...] and invite efforts to place ownership of American assets in persons or firms whose sovereign assures secrecy of records.

In light of this ruling it is no surprise then that US Courts are often unwilling to surrender sovereignty over the judicial process, even to the point of imposing "directly conflicting obligations" on a foreign party.28 This was notably the case with the Bank of China ("BOC") in the Gucci Trio of cases.29 In this matter involving an action under the Lanham Act, a US Court ordered the BOC to freeze the assets of Chinese defendants suspected of counterfeiting (Gucci I). On remand from the Court of Appeal's decision ("Gucci II"), District Judge Sullivan asserted personal jurisdiction over the BOC and granted Gucci's motion even though this would force BOC to violate Chinese law ("Gucci III"):30

Although BOC asks the Court to consider the fact that granting Gucci's motion would force BOC to violate Chinese law, BOC cites to no other courts that have considered such arguments in the context of assessing the reasonableness of an exercise of personal jurisdiction, as opposed to a separate and subsequent comity analysis, and the Court declines to be the first.

In another ruling, Wultz v Bank of China, the US Court compelled production of foreign electronically stored data despite the knowledge that doing so was illegal under Chinese state secret laws.31 Rather than have the best of both worlds, the BOC was caught in a battle for judicial sovereignty between two of the world's superpower legal systems.

Nevertheless, when performed as an analysis that is separate from a personal jurisdiction enquiry, the doctrine of international comity may in some cases successfully limit jurisdictional discovery and asset freeze orders from US judges. This was certainly a signal from the Second Circuit in Gucci II:32

[E]ven where personal jurisdiction over a foreign non-domiciliary is established, a court should not uphold an international subpoena in possible contravention of foreign law, without first performing a comity analysis pursuant to Section 442 of the Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law.

This ruling in Gucci II was more conciliatory than that of the Court in Gucci I & III. The former considered an order issued against BOC from the Beijing Second Intermediate People's Court that conflicted with Gucci I,33 evidence from a Chinese law expert attesting to the direct conflict of law, Chinese official concerns on the order's effects on China-US relations, and an amicus brief from the US government (then under the Obama administration) arguing for vacatur.34In at least one case similar to Gucci, Tiffany (NJ) LLC v. Qi Andrew,35 the Court was also persuaded by the BOC and the Industrial Bank of China, and accommodated their request not to disclose customer records for fear of exposing them to Chinese civil and criminal liability.

The holdings from these two conflicting strings of New York cases left the law on jurisdictional discovery unclear and unpredictable. In fact, the parties to a similar string of cases involving the Lanham Act, the Nike cases (Nikes "I", "II", "III", "IV", and "V", together the "Nike Quintet"), expressly agreed to hold off on further litigation until resolution of the Tiffany case and the Gucci Trio.36 36] In the Nike Quintet, Next (successor-in-interest for Nike) had succeeded in obtaining jurisdictional discovery, production, and asset freeze orders against the BOC and other Chinese banks in 2013.37

However, eight years later in Nike V, Next failed to convince the Second Circuit Court that the defendants should be sanctioned for failing to extend these orders to their banks located in China.38 The reason? Ironically, because even after Tiffany and the Gucci Trio, the law remains somewhat unclear on the subject. The legal circumstances of this case set the burden on Next to show why these orders apply abroad, and the Court in Nike V was persuaded that Next had failed to do so because (without ruling, like the Nike IV district Court that it affirms did, on the correctness of BOC's arguments) BOC raised reasonable arguments (specifically, a "fair ground of doubt") that, due to both comity concerns and New York's separate entity rule, the orders do not clearly apply to banks in China.39 Next's delay in bringing the action also frustrated the Court,40 making it unclear whether acting earlier against BOC to enforce the orders in Nike I would have made a difference. Nike V also affirms important parts of Nike III (itself affirming Nike II),41 most notably how they allow the Nike I discovery order to accommodate Chinese banking laws (allowing China's MOJ to select and forward permitted documents to the US). Despite this, it is made clear in Nike II that the US' interest in enforcing Lanham Act judgments against counterfeiters outweighs China's interest in enforcing bank secrecy laws.42

The easiest conclusion to draw from these cases involving the BOC is that while the Second Circuit encourages a fulsome comity analysis when considering discovery requests, results from Second Circuit cases like Gucci II, Tiffany and Nike V remain difficult to replicate because narrowing such requests remains a case-by-case determination. On this point, Gucci II and the Nike Quintet support reliance on a comity analysis based on Section 442 of the Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law. Under this approach, the Court must select and weigh five factors (like in Gucci II), or seven if the Court is considering a contempt motion (as in Nikes II and III),43 in a balancing test to determine whether to limit foreign discovery against a foreign litigant: (1) the documents or information's importance to the litigation, (2) the degree of specificity of the request, (3) whether the information originated in the United States, (4) the availability of alternative means of securing the information, and (5) the extent to which noncompliance with the request would undermine important interests of the United States or compliance with the request would undermine important interests of the state where the information is located.44 These factors vary even among similar cases and leave considerable room for discretionary analysis.

From a policy perspective, serious contempt orders from Chinese courts might help dissuade US Courts from placing Chinese litigants between Scylla and Charybdis. One practitioner's insight on why US Courts force Chinese defendants to violate Chinese laws in order to comply with US laws is revealing: "U.S. courts are no longer convinced that there is a credible threat of punishment for violating the PRC bank secrecy laws [...] While foreign laws purport to prohibit disclosure, governments generally do not impose penalties on their banks for complying with U.S. court orders."45 This analysis is consistent with the results in Nike I, Wultz, and Gucci III, where in the latter case the Court imposed a USD $50,000 contempt order for every day the BOC failed to comply with the Court's production order. While it is harder to square with the more recent Nikes II through V, that line also affirmed that China's bank secrecy laws are not a "get out of jail free" card,46 and that banks cannot "hide behind Chinese bank secrecy laws as a shield,"47 suggesting that the Nike Quintet is not intended to afford significantly more leniency towards litigants trying to use foreign legal restrictions to check US discovery requests.

Of course, different facts or circumstances may lead to narrower jurisdictional discovery orders. A US Court may be more amenable to narrowing jurisdictional discovery against a Chinese litigant if the underlying claim is not grounded in the Lanham Act. Moreover, requiring a Chinese bank to disclose information on a state-owned enterprise or government official, rather than a counterfeiter, could involve a more persuasive sovereign-immunity defense.48 Under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, jurisdictional discovery is generally allowed only to confirm specific facts that are crucial to the immunity determination.49

Finally, to further narrow discovery, retaining US-licensed counsel allows Chinese litigants to benefit from the same rules of legal privilege enjoyed by US litigants. There are risks to having no US counsel at all, because US Courts do not recognize any Chinese analogy to legal privilege. This was at issue in the aforementioned case Wultz v Bank of China, where the Court compelled the production of documents governed by Chinese law, on the grounds that a Chinese lawyer's duty of confidentiality falls short of US-style attorney-client privilege:50

Because attorney-client and work-product communications and documents could be subject to discovery under Chinese law, applying Chinese privilege law does not "violate principles of comity" or "offend the public policy of this forum."

[...]

Because Chinese law does not recognize the attorney-client privilege or the work-product doctrine, Bank of China must produce those items listed on its privilege log which are governed by Chinese privilege law.

Does this mean US-licensed attorneys can, merely by laying eyes on the communications records of foreign counsel, earn the right to affix upon said documents "attorney-client privileged" in bold letters? While having US-licensed counsel certainly helps establish privilege abroad, US law on this point is far more nuanced. US Courts adopt the "touch-base" approach to applying privilege to foreign documents. In the words of the Court in another case (also involving Gucci), Gucci America, Inc. v Guess?, Inc.:51

"[C]ommunications relating to legal proceedings in the United States, or that reflect the provision of advice regarding American law, 'touch base' with the United States and, therefore, are governed by American law, even though the communication may involve foreign attorneys or a foreign proceeding.

[...]

[such communications should] have a 'more than incidental' connection to the United States."

Therefore to benefit from US-style privilege against US proceedings involving Chinese evidence, it is not enough to simply have an American lawyer in the room. The document must be relating to or in anticipation of legal proceedings in the US, or otherwise provide advice involving the US, and that advice's connection to the US must be more than incidental. It is certainly not enough to simply stamp "attorney-client privileged" on every page if the "touch-base" requirement is not satisfied.

Conclusion

Discovery into personal jurisdiction is intended to be narrower than ordinary discovery. That said, it is stubbornly difficult to narrow any further. US Courts tend to favour domestic interests even at the expense of international comity, whether by applying the FRCP over the Hague Evidence Convention or by requiring foreign banks to violate home country laws to comply with discovery orders. This is especially the case with Lanham Act claims.

Invoking a violation with home country laws did, in some cases (Tiffany, Gucci II, Nikes II & III) successfully narrow discovery. However this is not the rule and is instead a case-by-case determination following the five-factor comity analysis endorsed by Gucci II. US Courts are generally not persuaded that complying with their discovery orders will lead to at-home sanctions, and until such sanctions begin to appear, it is unlikely that the policy fundamentals on this point will change. Courts are aware that litigants in such cases caught between Scylla and Charybdis will, like Odysseus, steer their compliance efforts down the path that harms them the least.

Footnotes

1. Homer, Iliad, The Odyssey, 12.235 ("For on one side lay Scylla and on the other divine Charybdis terribly sucked down the salt water of the sea").

2. (1945) 326 U.S. 310.

3. See comment in Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California (2017) 137 S. Ct 1773 at 1780; 198 L. Ed. 2d 395 ("Since our seminal decision in International Shoe, our decisions have recognized two types of personal jurisdiction: 'general' (sometimes called 'all-purpose') jurisdiction and 'specific' (sometimes called 'case-linked') jurisdiction."); see also Xin Xu, "Show Me the Money: Evaluating Personal Jurisdiction over Foreign Nonparty Banks in Light of the Gucci Case" Cornell Intl L J, Vol 49, Issue 3 (Fall 2016) at 749, which posits another line of thinking that this distinction only emerged after International Shoe in Helicopteros Nacionales de Colombia, S. A. v. Hall, 466 U.S. 408, 414 (1984).

4. Arthur T. von Mehren & Donald T. Trautman, "Jurisdiction to Adjudicate: A Suggested Analysis" (1966) 79 Harv L. Rev. 1121, 1136.

5. Goodyear Dunlop Tires Operations, S.A. v. Brown, 131 S. Ct. 2846 (2011).

6. Daimler AG v. Bauman, 134 S. Ct. 746 (2014), which found that Courts may exercise general jurisdiction only when the corporation is "essentially at home" in the forum state, replacing the previous "continuous and systematic general business contacts" test, which was "unacceptably grasping."

7. Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, 253 (1958) (discussing purposeful availment);

8. Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462, 472 (1985) (Burger King), applying the concept of relatedness created in International Shoe v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316- 18 (1945).

9. Burger King, 471 U.S. at 477-78.

10. Lea Brilmayer, A General Look at Specific Jurisdiction, 42 Yale J. Int'l L. Online 1, 5 (2017).

11. Howard M. Erichson, John C. P. Goldberg & Benjamin C. Zipursky, Case-Linked Jurisdiction and Busybody States, 105 Minn. L. Rev. Headnotes 54 (2020) at 55 (n 6: "For example, [Courts] do not like specific jurisdiction premised solely on the plaintiffs contact with the forum state. See Walden v. Fiore, 571 U.S. 277, 284 (2014). Nor do they like a sliding scale approach that merges general jurisdiction with specific jurisdiction. See Bristol-Myers Squibb, 137 S. Ct. at 1781.").

12. Ray Worthy Campbell & Ellen Claar Campbell, Clash of Systems: Discovery in U.S. Litigation Involving Chinese Defendants, 4 PEKING U. Transnat'l L. REV. 129 (2016) at 156.

13. Ibid at 157, describing Germano v. Taishan Gypsum Co. (In re Chinese Manufactured Drywall Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2047, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 183686 (E.D. La. July 17, 2014). See also ibid, n 88 citing Gucci Am., Inc. v. Huoqing, No. C-o9-o5969 JCS, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 783, at 63 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 3, 2011), where Huoqing was forbidden from doing further business in the USA following a series of counterfeiting and trademark violations against the plaintiff.

14. Gucci Am., Inc. v. Weixing Li, No. 10 Civ. 4974 (RJS), 135 F. Supp. 3d 87 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 29, 2015) (Gucci III), reaffirming on remand from Gucci Am., Inc. v. Bank of China, No. 11-3934-cv (2d Cir. Sep. 17, 2014) (Gucci II) the asset freeze and document production request in Gucci Am., Inc. v. Weixing Li, No. 10 Civ. 4974 (RJS), 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 97814 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 23, 2011) (Gucci I, vacated on other grounds, together the "Gucci Trio"). For a detailed discussion of this trio of rulings, see Xin Xu, "Show Me the Money: Evaluating Personal Jurisdiction over Foreign Nonparty Banks in Light of the Gucci Case" Cornell Intl L J, Vol 49, Issue 3 (Fall 2016).

15. In re Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Prods. Liab. Litig., 753 F.3d 521 (5th Cir. 2014); In re Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Prods. Liab. Litig., 742 F.3d 576 (5th Cir. 2014).

16. 137 S. Ct.

17. In re Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Prods. Liab. Litig., Doc. 22460, MDL NO. 2047 [Jan 10, 2020], online: (www.laed.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/drywall/09-2047%20%28Drywall%29%20-%20Final%20Approval.pdf)

18. Ibid at 12.

19. Hague Evidence Convention PRC, Hong Kong & Macau Reservations, HCCH, online: (www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/statustable/notifications/?csid=493&disp=resdn) (last visited Aug. 16, 2021).

20. Ray Worthy Campbell & Ellen Claar Campbell, Clash of Systems: Discovery in U.S. Litigation Involving Chinese Defendants, 4 Peking U. Transnat'l L. Rev. 129 (2016) at 153.

21. Ibid.

22. Societe Nationale Industrielle Aerospatiale v. U.S. Dist. Court for S. Dist. of Iowa, 482 U.S. 522 (1987).

23. Gucci I at *27 (upheld in part, vacated on other grounds).

24. Ray Worthy Campbell & Ellen Claar Campbell, Clash of Systems: Discovery in U.S. Litigation Involving Chinese Defendants, 4 Peking U. Transnat'l L. Rev. 129 (2016) at 154.

25. Ray Worthy Campbell & Ellen Claar Campbell, Clash of Systems: Discovery in U.S. Litigation Involving Chinese Defendants, 4 Peking U. Transnat'l L. Rev. 129 (2016) at 163 (Article 2 requires Chinese Citizens to guard against revealing "state secrets", and Article 30 requires State pre-approval before furnishing some of them to others).

26. Data Security Law of the People's Republic of China, National People's Congress, 13th sess., Standing Committee, 29th sess., enacted June 10, 2021, arts 36, 48, online (unofficial English translation): (www.cov.com/-/media/files/corporate/publications/file_repository/data-security-law-bilingual.pdf) (art 48 reads: "Where entities violate requirements under Article 36 of this Law and provide data to overseas judicial or law enforcement organs without obtaining approval from competent authorities, departments performing data security duties shall issue warnings [sic] impose a fine ...").

27. 357 U.S. 197, 205 (1958) at 204.

28. Gucci II, Dkt. 346, 09/17/2015.

29. 15 U.S.C. § 1051.

30. Gucci III, at 99; see also ibid quoting Licci, 732 F.3d at 171 (the banks' "in-forum conduct is deliberate and recurring, not 'random, isolated, or fortuitous. ... the selection and repeated use of New York's banking system ... constitutes 'purposeful availment of the privilege of doing business in New York.").

31. Wultz v. Bank of China Ltd., 942 F. Supp. 2d 452, 466, 473 (S.D.N.Y. 2013); see also Societe Nationale Industrielle Aerospatiale v. U.S. Dist. Court for S. Dist. of Iowa, 482 U.S. 522, 546 (1987).

32. Gucci II, at 141; per Linde v. Arab Bank, PLC, 706 F.3d 92, 111 (2d Cir. 2013) (quoting Societe Nationale Industrielle Aerospatiale, 482 U.S. at 543-44, 107 S.Ct. 2542) this analysis must weigh "all of the relevant interests of all of the nations affected by the court's decision." See also Nike II, infra, which quotes this reasoning.

33. Gucci II, Dkt. 346, 09/17/2015.

34. Ray Worthy Campbell & Ellen Claar Campbell, Clash of Systems: Discovery in U.S. Litigation Involving Chinese Defendants, 4 Peking U. Transnat'l L. Rev. 129 (2016) at 170.

35. 276 F.R.D. 143 (S.D.N.Y. 2011). Interestingly, this and another Tiffany case, Tiffany (NJ) LLC v. Forbse, No. 11cv4976 (NRB), 2012 WL 1918866 (S.D.N.Y. May 23, 2012), are among the few Chinese precedents where evidence was produced through the Hague Evidence Convention. The result was deemed unsatisfactory by the Court (in both cases, the Chinese Ministry of Justice only "partly executed" the Hague Convention requests that the Ministry "deem[ed to] conform to the provisions of the [Hague] Convention," QI Andrew, 2015 WL 3701602, at *1 n.1). This was raised again in Nike II, infra.

36. Nike, Inc. v Wu (S.D.N.Y. 2020) WL 257475 at 3 ("Nike IV") ("the two sides agreed to put their dispute on hold until the Second Circuit ruled on two pending appeals in the Tiffany and Gucci cases, two other trademark infringement suits in which certain of the Chinese Banks were challenging the enforceability of discovery orders and prejudgment asset freezes overseas").

37. Ibid.

38. Next Investments, LLC v. Bank of China, No. 11-3934-cv (2d Cir. Aug. 30, 2021) ("Nike V").

39. Nike V at lines 11-2 ("there is a fair ground of doubt as to whether, in light of New York's separate entity rule and principles of international comity, the orders could reach assets held at foreign bank branches").

40. See ibid at 22 (Next's delay in bringing an action was not well regarded by the Second Circuit Court, noting that the district Court "refused to reward Next's "'gotcha' tactics" and other 16 efforts "to delay resolution" of key legal issues").

41. 349 F. Supp. 3d 310, 318 (S.D.N.Y. 2018) ("Nike II"), interestingly, Nike II like Gucci II allowed evidence from a Chinese law professor, Banks Mem., at 14-5, citing Guo Decl. ¶ 15-21.

42. Nike II at *339.

43. Per Linde v Arab Bank, PLC, 706 F.3d 9284 Fed.R.Serv.3d 961 at 110, a Second Circuit decision, when deciding whether to impose sanctions, a district court should also examine the [6] hardship of the party facing conflicting legal obligations and [7] whether that party has demonstrated good faith in addressing its discovery obligations. Note that for an asset freeze, the comity enquiry is different and relies instead on s. 403 of the Restatement (Limitations on Jurisdiction to Proscribe), Nike V, at 25 ("we eschew any categorical rule and instead draw on the eight-factor framework found in Section 403 of the 15 Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law.")

44. Societe Nationale Industrielle Aerospatiale v. U.S. Dist. Court for S. Dist. of Iowa, 482 U.S. 522, 546 (1987).

45. Meg Utterback, "Lessons from the GUCCI case: Chinese banks increasingly subject to U.S. jurisdiction", Lexology (Aug 29 2016), online: (www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=88f05267-e346-4e0d-8f6c-3a393e579ad3).

46. Nike III at *364.

47. Nike II, citing Gucci I at *10.

48. Ibid.

49. Laura G. Ferguson & Charles F. B. Mcaleer Jr, "Playing the Sovereign Card: Defending Foreign Sovereigns in US Courts", Litigation, Vol 43, No., 2, Winter 2017.

50. Wultz v. Bank of China Ltd., 979 F. Supp. 2d 479 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

51. U.S. Dist. Court 271 F.R.D. 58 (S.D.N.Y 2010).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.