In its World Energy Special Report, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions 2, the International Energy Agency (IEA or Agency) mentions that "Canada holds some of the world's most substantial reserves of many minerals, including some 15 million tonnes of rare earth oxides (NRCAN, 2020)." 3

As the Executive Director of the Agency, Dr. Faith Birol, says in her foreword to the Report: "Today, the global energy system is in the midst of a transition to clean energy. The efforts of an ever-expanding number of countries and companies are trying to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to net zero, and these efforts will call for a massive deployment of a wide range of clean energy technologies, many of which will in turn rely on critical minerals such as copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements." 4

For example, a typical electric car requires six times the mineral input of a conventional car; battery electric vehicles need lithium, cobalt, manganese and graphite, which are crucial to the performance, longevity and energy density of its battery. The Agency estimates that "a concerted effort to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement (climate stabilisation at 'well below 2° C global temperature rise,' as in the IEA Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS)) would mean a quadrupling of mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040. An even faster transition, to hit net-zero globally by 2050, would require six times more mineral inputs in 2040 than today." 5 The Agency writes that "[t]he prospect of a rapid increase in demand for critical minerals—well above anything seen previously in most cases—raises huge questions about the availability and reliability of supply." 6

What are the clean energy technologies?

- Solar photovoltaic, utility-scale and distributed

- Wind, onshore and offshore

- Concentrating solar power (parabolic troughs and central tower)

- Hydropower

- Geothermal

- Bioenergy for power

- Nuclear power

- Electricity networks (transmission, distribution, and transformation)

- Electric vehicles (battery, electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles)

- Battery storage (utility scale and residential)

- Hydrogen (electrolysers and fuel cells)

The IEA predicts that there will be 140 million electric vehicles in operation in the world in 2030 as opposed to 6.8 million in use globally in 2020. 7

The IEA is not the only organization that has drawn the attention of the public and policy-makers to the role of critical minerals in the energy transition. The World Bank, in its June 2017 report The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future 8, describes the problem as follows in the first sentence of the executive summary: "Climate and greenhouse gas (GHG) scenarios have typically paid scant attention to the metal implications necessary to realize a low/zero carbon future." 9

In the chapter devoted to the implication for developing countries, the Bank mentions Canada's place in the critical minerals space: "With respect to Asia, the most notable finding is the global dominance China enjoys on the metals—both base and rare earth—required to supply technologies in a carbon-constrained future. Both production and reserve levels, even when compared with resource-rich developed countries (such as Canada and the United States, and to a lesser extent Australia) often dwarf that of others." 10 The Bank adds that Canada is a producer of aluminium, cadmium, cobalt, iron one, indium, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, silver, titanium and zinc.

And in their conclusions, the authors say:

It is clear that meeting the Paris climate target of not exceeding two degrees Celsius (2° C) (and making best efforts to reach 1.5°C) global warming over this century will require a radical (that is, to the root) restructuring of energy supply and transmission systems globally.

[...]

Key base metals including copper, silver, aluminium (bauxite), nickel, zinc, and possibly platinum, among others, are expected to benefit from a low carbon energy shift over the century. Key rare earth metals (at least for the three technologies analyzed in depth in this study) are neodymium and indium, among others. 11

The Agency states that it takes an average of 16 years to move mining projects from discovery to production. These long lead times may raise questions about the ability of suppliers to increase their output if, as is widely assumed, demand were to pick up.

Will we have enough of the critical minerals in time for all the electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels that are the backbone of the energy transition? This is the challenge that governments will face as they look to adhere to the goal of the Paris Agreement.

And this is the question Fasken modestly attempts to answer in this series, from a Canadian perspective – a country with a relatively small population, but vast regions with enormous mineral resources.

In this series we review what the Canadian government and provincial and territorial governments have done and plan to do to ensure that Canada can produce enough of these critical minerals to help power the energy transition. What is clear is that as a country we do a lot to encourage the demand for electric vehicles, but there is far less clarity when it comes to the government policies necessary to spur the supply of the critical minerals that are necessary to power those electric vehicles.

And, being lawyers, we will pay special attention to the issue of regulatory certainty: can mining companies expect an expeditious permitting process, or will there be opposition to the development of lithium, cobalt or manganese mines similar to other mining projects? Will public authorities greenlight these projects quickly to support the energy transition or will we witness a business as usual approach?

In this instalment, the first of seven, Fasken lawyers with experience in mining, energy, environmental, Indigenous, climate change, tax, and national security law examine the initiatives that the Canadian federal government has taken so far to encourage the exploration and mining of critical and strategic minerals.

Future instalments will examine what the governments of Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, the Prairies provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba), the Atlantic provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia), and the territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut) have done or propose to do.

Canadian Federal Initiatives

In 2019, the Canadian government released the Canadian

Minerals and Metals Plan (the Plan), 12 which sets a

policy to establish Canada as a leading mining country for

sustainable and responsible critical minerals.

National Resources Canada has developed the following list of Canadian Critical Minerals:

|

|

|

|

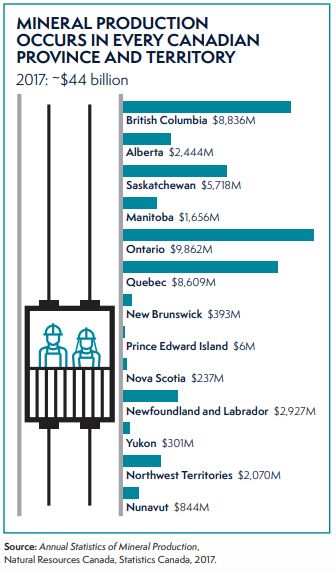

The Plan's opening sentence states boldly that "Canada is a global mining powerhouse," 13 with Ontario, British Columbia and Québec highlighted as being the most active mining provinces.

The Plan clearly recognizes the link between critical minerals and the transition to clean energies:

Mining delivers the inputs that power our digital age. Canada ranks third in the global production of aluminium, fourth in cobalt, and fifth in nickel. It is primed to meet increasing demand for graphite, lithium and rare earth elements. Canada is a key producer of copper, an important metal for items that plug in—electric vehicles, medical equipment, smart phones and appliances, to name a few. All of these products are key for clean technologies, such as wind turbines, solar panels, batteries and energy storage units, transmission lines, wiring for electric vehicles, and other low carbon applications. 14

The Plan is optimistic about the upward trajectory of demand for minerals and metals, stating that: "Demand for minerals and metals should be driven by emerging markets as the middle classes of China and India continue to grow, buy products and services, and adopt clean technologies such as wind and solar power and electric vehicles that rely on mining products." 15

Throughout the Plan, there are several pages devoted to the role of the Indigenous peoples of Canada; the perspectives of Indigenous peoples are in fact meant to be represented throughout the Plan. 16 In Canada the provinces and territories, not the federal government, have jurisdiction over property, land and natural resources (including mineral resources). Often, mineral resources are located within the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples who assert Aboriginal rights and title. The Plan emphasizes the role that the federal, provincial and territorial governments have in respect of Indigenous peoples, in particular their unique role as set out in Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, which states that the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are "recognized and affirmed." As a result of this constitutional protection, in appropriate circumstances, the Crown has a duty to consult with Aboriginal peoples and, potentially, to seek workable accommodation of their interests before making decisions that may affect their ability to exercise their constitutionally-protected rights. The type of decision that may require consultation and possibly accommodation often relates to resource development or land access activities, such as oil and gas, forestry, energy, mining, land development or fisheries. These decisions may be at the "operational" level, such as granting approvals for cutting permits, seismic work, access roads, well sites, pipelines and other facilities, or they may be at a "strategic" level, such as approving land sales, the transfer of assets and large project approvals.

Ultimately, the Crown must manage natural resources, including mineral resources, by weighing and balancing its responsibility to Indigenous peoples with other stakeholders' interests. In this regard, the Crown relies on the cooperation of Indigenous peoples and industry in providing it with the information to make the correct determinations of law, to institute a process of consultation that fits the circumstances, and to ensure the appropriate form of accommodation is implemented. Regulatory certainty can be advanced by following good practices that facilitate engagement with Indigenous peoples and stakeholders as early as possible to provide opportunities for communities to participate in all stages of the development of a project with a view to allowing Indigenous businesses to mature in lockstep with projects through capacity-building, procurement and other opportunities.

The March 2020 preliminary version of the Action Plan devotes a detailed section to "Advancing the Participation of Indigenous peoples" and the September 2020 Update to Action Plan 2020 lists current initiatives by federal, provincial and territorial governments and associations such as the following: 17

- $1.58 million to support early reclamation work at the Tulsequah Chief Mine site in collaboration with the Taku River Tlingit First Nation (B.C., Indigenous peoples);

- Passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples Act (B.C.);

- Funding for emissions-reduction such as electrification and fuel switching at mining operations under the CleanBC Industry Fund (B.C.);

- Developing a First Nations procurement policy (Y.T.);

- Sharing fiscal benefits from resource revenues with Indigenous Governments that are signatories to the Northwest Territories Lands and Resources Devolution Agreement (N.W.T.);

- Indigenous governments releasing or developing regional mineral development strategies (Indigenous peoples, N.W.T.);

- New Mineral Resources Act contains provisions for Indigenous governments and organizations, communities and residents to realize benefits from mineral development (N.W.T.);

- Established La Grande Alliance for a 30-year infrastructure program to facilitate transportation and increase the value of natural resources (Que., Cree Nation).

One of the areas for action identified in the Plan relates to tax and financial incentives. It is suggested that the federal, provincial and territorial governments review Canada's tax position and adjust tax policies and other fiscal instruments to support cost competitiveness and attract investment.

Canada's tax policy in the mining sector recognized early that the sector required specially targeted measures to take in to account the capital-intensive needs of the sector, as well as its unique revenue cycle.

In this context, Canada's tax competitiveness is currently achieved through several measures that include one of the lowest effective tax rates among international mining jurisdictions, and tax incentive measures that help the industry raise much needed funding, such as its Flow-Through Shares mechanism (in effect for more than 35 years), harmonized with the Mineral Exploration Tax Credit and some provincial measures. Provinces have adopted separate measures, which apply in addition to the federal measures, such as additional deductions for investors in Flow-Through Shares that help fund the mineral exploration activities, and income tax credits.

These measures have helped junior mining companies raise funds to finance mineral exploration through equity markets, as they do not have internally generated revenue and thus cannot make use of the deduction of exploration expenses incurred by them. As briefly described herein, the use of Flow-Through Shares to fund mineral exploration enables the mining company to pass on to subscribers of Flow-Through Shares, the deduction in computing income for the exploration expenses it incurs.

The Plan aims to increase the importance of the mineral sector in Canada's national economy and articulates six strategic directions:

1) Economic Development and Competitiveness: Canada's business and innovation environment for the minerals sector is the world's most competitive and most attractive for investment

2) Advancing the Participation of Indigenous peoples: Increased economic opportunities for Indigenous peoples and supporting the process of reconciliation

3) The Environment: The protection of Canada's natural environment underpins a responsible, competitive industry. Canada is a leader in building public trust, developing tomorrow's low-footprint mines and managing the legacy of past activities

4) Science, Technology and Innovation: A modern and innovative industry supported by world-leading science and technology across all phases of the mineral development cycle

5) Communities: Communities welcome sustainable mineral development activities for the benefits they deliver.

6) Global Leadership: A sharpened competitive edge and increased global leadership for Canada

Interestingly, the Plan addresses the issue of climate adaptation:

Adaptation to climate change is an emerging issue for industrial sectors. For mining, it brings factors such as additional maintenance and repairs to infrastructure, the potential for environmental impacts from the failure of storage facilities, and impacts from extreme weather events such as floods, droughts and wildfires. For workers and communities, it can mean potential work shutdowns, impacts on hunting, trapping and fishing, and impacts on housing and social infrastructure.

In the North, warmer temperatures and melting permafrost bring additional challenges, including for transportation systems that rely on winter roads.

Environmental assessments of projects in the North require analysis to ensure that current and future permafrost conditions have been properly considered in mine plans.

The majority of existing Canadian mines were designed to operate within particular climatic parameters, and to manage the risk of weather events occurring at specific intervals (e.g. one- and 50-year storms). Abandoned mines represent a higher level of risk, particularly where infrastructure and technologies may not have been designed for the full range of future climatic conditions. Increased climate-related risks must be considered in planning, and additional measures may be required to ensure the stability of waste rock and tailings impoundments. 18

The Plan also addresses the issue of regulatory certainty but, perhaps not surprisingly, does not discuss criticisms that are sometimes made about Canada's permitting process and lack of regulatory certainty, especially with respect to environmental assessment. That said, the Plan, under the title "Economic Development and Competitiveness" 19, describes the following goals:

And, the Plan adds that by 2020, there should be "Gains in the stability, predictability and effectiveness of regulatory regimes for the minerals industry and Canadians." 20

The Plan does not address the issue of regulatory uncertainty which has plagued big projects; quite the opposite, the plan shifts the onus of regulatory compliance to promoters of projects:

Regulations must safeguard the interests of Canadians. Regulatory systems that are strong, agile, transparent, and predictable are a competitive advantage, as they protect the environment, facilitate sound project planning and provide investors with a clear path to timely project approvals.

[...]

Many mining projects are subject to both federal and provincial environmental assessments and other legislation. There is a separate environmental assessment process for Canada's three territories, which satisfies federal and territorial jurisdictions.

The time it takes to complete environmental assessments and obtain a project decision is an important factor in the economic attractiveness of a mining project. Decisions should be based on evidence including science and local knowledge, and be delivered within defined timelines.

This instils investor confidence and

can reduce the time between mineral discovery, or the acquisition

of a mineral deposit, and production.

Regional assessments could offer opportunities to identify,

analyze, and manage potential cumulative environmental, economic,

social and cultural effects at a local or regional scale. This

approach could have the potential to streamline approvals at the

project level, provide greater clarity on a region's capacity

for activity, and support regional development. 21

Current Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) concerns among investors and bankers should help Canadian producers. Canada scores very high on the transparency index. The country is known for being committed to a strong regulatory regime. Such a reputation ensures investors that their investment is protected by high environmental and social standards.

In 2020, Canada and the United States signed a Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration. 22

The joint action plan, which was signed on January 9, 2020, by Prime Minister Trudeau and President Trump, delivers on their commitment to "improve critical mineral security and ensure the future competitiveness of Canadian and US minerals industries."

The areas of collaboration between the two countries include:

- industry engagement;

- securing supply chains for strategic industries and defence; and

- data exchange multilateral cooperation.

In the next few paragraphs, when we will look at the report of the US Department of Energy we will examine the US list of critical minerals but for the moment it is worth stressing that Canada is described as a secure supplier for 13 of the US critical minerals: cesium, rubidium, potash, tellurium, uranium, indium, vanadium, niobium, titanium, magnesium, tungsten and graphite. Recall that previous versions of Canada's Critical Mineral list indicated minerals critical not to Canada but rather, to its allies. In the most recent version, Canada has adopted a more specifically self-interested accounting of its minerals needs.

A comparison of the Canadian and American approaches to critical minerals is beyond the scope of this article, but there are some interesting items to note in the report of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Critical Minerals and Materials 23 states that: "The US-Canada Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration signed in early 2020 has the potential to be highly productive in view of the vast mineral resources of Canada, its historical strengths in mining and metallurgy, and the common interests between these nations." 24

The first paragraph of the executive summary of this report reads as follows:

Critical minerals and materials are used in many products important to the United States economy and national security. Thus, the assured supply of critical minerals and materials and the resiliency of their supply chains are essential to the economic prosperity and national defence of the United States. Of the 35 mineral commodities identified as critical in the list published in the Federal Register by the Secretary of the Interior, the United States lacks domestic production of 14 and is more than 50 per cent import-reliant for 31. This import dependence puts industrial supply chains, United States companies, and material users at significant risk. 25

The 35 minerals commodities that are of critical importance to the economy and defence of the United States are: Aluminium (bauxite), antimony, arsenic, barite, beryllium, bismuth, cesium, chromium, cobalt, fluorspar, gallium, germanium, graphite (natural), hafnium, helium, indium, lithium, magnesium, manganese, niobium, platinum group metals, potash, the rare earth elements group, rhenium, rubidium, scandium, strontium, tantalum, tellurium, tin, titanium, tungsten, uranium, vanadium, and zirconium. The underlined minerals are also found in the list of Canadian Critical Minerals.

Canada, it should be said, is not without a sense of its strategic positioning in the global order. Nor is it unaware of its potential as a key supplier of critical minerals. Indeed, as refenced above, until the most recent edition of its critical minerals list, Canada defined criticality by reference to elements it possessed and others needed – not those minerals it needed, per se. What Canada has sometimes failed to do is draw the straight line between critical minerals and its essential security interests. The U.S. has no such reluctance, stating clearly in Executive Order 13953 of September 30, 2020 that undue reliance on Chinese sourced rare earth elements had threatened allied industrial and defence sectors and disrupted rare earth element prices worldwide. The closest Canada has come to such statements is in its revised (2021) Guidelines on the National Security Review of Investments in which the potential impact of a foreign investment on critical minerals and critical mineral supply chains is referenced but not elaborated. 26

Also, in 2020, Canada joined the US-led Energy Resource Global Initiative as one of its founding members, alongside the United States, Australia, Peru and Botswana, to promote a sound mining sector governance and resilient global supply chains for critical minerals. These five countries aim to disseminate best mining practices around the world, from the discovery of mineral resources to the closure and reclamation of mines.

In Canada, both the federal and the provincial governments levy income taxes, and both levels of government have provided for incentives relating to exploration activities and expenses in Canada.

The incentives for the exploration corporations take the form of deductions of exploration expense and expenses in development in computing income, the issuance of Flow-Through Shares and the availability of certain tax credits.

For investors, the incentives take the form of the availability of deducting an amount in respect of the exploration expenses incurred by the exploration corporation from the proceeds of issuance of Flow-Through Shares, and additional tax credits and, in certain cases, such as in Québec, an exemption from the gain on the sale of the shares.

The Flow-Through Share mechanism is unique to the resource sector in Canada, and provides that a corporation can renounce exploration expenses in favour of holders of Flow-Through Shares.

As a result of this renunciation, subscribers are entitled to a 100% deduction of the exploration expenses renounced. In other words, a corporation incurring Canadian Exploration Expense can choose to effectively transfer its right to a deduction in respect of exploration expenses, and consequently, forego any such deduction.

This is particularly important to Canadian exploration corporations, as many may not be in a position of having income to make use of the deductions for exploration expenses they incur.

A particularly salient aspect of the Flow-Through Share mechanism is known as the "look back rule", which allows a corporation to not only renounce expense in the current and subsequent year, enabling to investors to deduct in the current year expenses incurred by the issuer in the current year, and investors may also deduct in the current year expenses to be incurred in the following year by the issuing corporation.

The federal incentives also include the possibility for investors to claim an investment tax credit (currently at 15%) with respect to current expenses or expenses to be incurred in the next year by the corporation. Some provinces also provide a tax credit available to the investors.

Finally, Québec has also provided for two noteworthy incentives: (i) additional deductions for investors in respect of the exploration expenses renounced by the exploration corporation, thus providing for up to 120% deductions in computing income; (ii) a mechanism to exempt from income tax on the gain on the sale of shares of certain exploration corporations; and (iii) and the possibility for exploration corporation to claim an income tax credit on exploration expense not renounced by the corporation.

In the next instalment of this series, we will examine what Québec has done to promote the exploration and mining of critical minerals. Québec is the only province or territory in Canada that has completed a plan dedicated specifically to that issue.

Footnotes

1 The Authors wish to thank Claude Jodoin (Tax), Janet Howard (Electricity), Allison Sears (Hydrogen), Andrew House (National Security), and Emilie Bundock (Indigenous law) for their contributions.

2 Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/24d5dfbb-a77a-4647-abcc-667867207f74/TheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitions.pdf [The Report]

3 The Report, page 164

4 The Report, page 1

5 The Report, page 8

6 The Report, page 11

7 Source: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/af46e012-18c2-44d6-becd-bad21fa844fd/Global_EV_Outlook_2020.pdf

8 Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/207371500386458722/pdf/117581-WP-P159838-PUBLIC-ClimateSmartMiningJuly.pdf [The Growing Role Report]

9 The Growing Role Report, page xii

10 The Growing Role Report, page 27

11 The Growing Role Report, page 58

12 Available online: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/CMMP/CMMP_The_Plan-EN.pdf [The Plan]

13 The Plan, page 1

14 The Plan, page 2

15 The Plan, page 9

16 The Plan, page 15; Preliminary Version of Action Plan 2020, page 9.

17 Action Plan 2020 Update, page 8.

18 The Plan, page 26

19 The Plan, page 7

20 The Plan, page 7

21 The Plan, pages 10-11

22 The Joint Action Plan itself is not

available online.

In the meantime, the Saskatchewan Mining Association published a

PowerPoint Presentation of Natural Resources Canada presenting the

Joint Action Plan of the 54th Annual General Meeting: Saskatchewan

Mining Association: http://saskmining.ca/ckfinder/userfiles/files/Plenary%20Session%201%20Update%20on%20Canada-US%20Action%20Plan%20(Hilary%20Morgan).pdf

Also the government of Canada released an unsigned version of a

Memorandum of understanding in August 2020: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/resources/international-energy-cooperation/memorandum-understanding/23749

23 Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2021/01/f82/DOE%20Critical%20Minerals%20and%20Materials%20Strategy_0.pdf The US Report

24 The US Report, page 23

25 The US Report, page i

26 https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/ica-lic.nsf/eng/lk81190.html

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.