Drafting of liquidated damages clauses

Given the role liquidated damages play in ensuring EPC contracts are bankable, and the consequences detailed above of the regime not being effective, it is vital to ensure they are properly drafted to ensure contractors cannot avoid their liquidated damages liability on a legal technicality.

Therefore, it is important, from a legal perspective, to ensure DLDs and PLDs are dealt with separately. If a combined liquidated damages amount is levied for late completion of the works, it risks being struck out as a penalty because it will overcompensate the project company. However, a combined liquidated damages amount levied for underperformance may under compensate the project company.

Our experience shows that there is a greater likelihood of delayed completion than there is of permanent underperformance. One of the reasons why projects are not completed on time is contractors are often faced with remedying performance problems. This means, from a legal perspective, if there is a combination of DLDs and PLDs, the liquidated damages rate should include more of the characteristics of DLDs to protect against the risk of the liquidated damages being found to be a penalty.

If a combined liquidated damages amount includes a NPV or performance element, the contractor will be able to argue that the liquidated damages are not a genuine preestimate of loss when liquidated damages are levied for late completion only. However, if the combined liquidated damages calculation takes on more of the characteristics of DLDs the project company will not be properly compensated if there is permanent underperformance.

It is also important to differentiate between the different types of PLDs to protect the project company against arguments by the contractor that the PLDs constitute a penalty. For example, if a single PLDs rate is only focused on availability and not efficiency, problems and uncertainties will arise if the availability guarantee is met but one or more of the efficiency guarantees are not. In these circumstances, the contractor will argue that the PLDs constitute a penalty because the loss the project company suffers if the efficiency guarantees are not met are usually smaller than if the availability guarantees are not met.

Drafting of the performance guarantee regime

Now that it is clear that DLDs and PLDs must be dealt with separately, it is worth considering, in more detail, how the performance guarantee regime should operate. A properly drafted performance testing and guarantee regime is important because the success or failure of the project depends, all other things being equal, on the performance of the wind farm.

The major elements of the performance regime are:

- Testing

- Guarantees

- Liquidated damages.

Liquidated damages were discussed above. Testing and guarantees are discussed below.

Testing

Performance tests may cover a range of areas. Three of the most common are:

Functional tests – these test the functionality of certain parts of the wind turbine generators. For example, Scada systems, power collection systems and meteorological masts, etc. They are usually discrete tests which do not test the wind farm as a whole. Liquidated damages do not normally attach to these tests. Instead, they are absolute obligations that must be complied with. If not, the wind farm will not reach the next stage of completion (for example, mechanical completion or provisional acceptance).

Guarantee tests – these test the ability of the wind farm to meet the performance criteria specified in the contract. For instance, a requirement to meet a specified power curve or an availability guarantee to meet the minimum quantity of electricity required under the PPA. The consequence of failure to meet these performance guarantees is normally the payment of PLDs. Satisfaction of the minimum performance guarantees is normally an absolute obligation. The performance guarantees should be set at a level of performance at which it is economic to accept the wind farm. Lender?s input will be vital in determining what this level is. However, it must be remembered that lenders have different interests to the sponsors. Lenders will, generally speaking, be prepared to accept a wind farm that provides sufficient income to service the debt. However, in addition to covering the debt service obligations, sponsors will also want to receive a return on their equity investment. If that will not be provided via the sale of electricity because the contractor has not met the performance guarantees, the sponsors will have to rely on the PLDs to earn their return. In some projects, the guarantee tests occur after hand over of the wind farm to the project company. This means the contractor no longer has any liability for DLDs during performance testing.

In our view, it is preferable, especially in project financed projects, for handover to occur after completion of performance testing. This means the contractor continues to be liable for DLDs until either the wind farm achieves the guaranteed level or the contractor pays PLDs where the wind farm does not operate at the guaranteed level. Obviously, DLDs will be capped (usually at 20% of the contract price), therefore the EPC contract should give the project company the right to call for the payment of the PLDs and accept the wind farm. If the project company does not have this right the problem mentioned above will arise, namely, the project company will not have received its wind farm and will not be receiving any DLDs as compensation.

It is often the case in wind farm projects that the contractor or operator of a wind farm will not accept liability for availability PLDs beyond a limited period. In a power plant, the PLDs are calculated to enable the owner to recover the amount it will lose over the life of the power plant in the event the heat rate, rated output or availability guarantees are not satisfied. The PLDs on a power plant are usually calculated using the net present value of the owner?s loss based on the life of the plant. On wind farm projects, the contractor will pay power curve PLDs but will often not accept responsibility for availability PLDs beyond the warranty period or in the case of the operator, the term of the operating and maintenance agreement. The contractor or operator, as the case may be, will simply pay the yearly availability PLDs for failing to meet the stipulated availability guarantee over the warranty period specified in the contract or for the period during which the operator has control over the operation and maintenance of the wind farm.

It is common for the contractor to be given an opportunity to modify the wind farm if it does not meet the performance guarantees on the first attempt. This is because the PLD amounts are normally very large and most contractors would prefer to spend the time and the money necessary to remedy performance instead of paying PLDs. Not giving contractors this opportunity will likely lead to an increased contract price both because contractors will build a contingency for paying PLDs into the contract price. The second reason is because in most circumstances the project company will prefer to receive a wind farm that achieves the required performance guarantees. The right to modify and retest is another reason why DLDs should be payable up to the time the performance guarantees are satisfied.

If the contractor is to be given an opportunity to modify and retest, the EPC contract must deal with who bears the costs required to undertake the retesting. The cost of the performance of a power curve test in particular can be significant and should, in normal circumstances, be to the contractor?s account because the retesting only occurs if the performance guarantees are not met at the first attempt.

Technical issues

Ideally, the technical testing procedures should be set out in the EPC contract. However, for a number of reasons, including the fact that it is often not possible to fully scope the testing program until the detailed design is complete, the testing procedures are usually left to be agreed during construction by the contractor, the project company?s representative or engineer and, if relevant, the lenders? engineer. However, a properly drafted EPC contract should include the guidelines for testing.

The complete testing procedures must, as a minimum, set out details of:

- Testing methodology – reference is often made to standard methodologies, for example, the IEC 61-400 methodology33.

- Testing equipment – who is to provide it, where it is to be located, how sensitive must it be.

- Tolerances – what is the margin of error. For instance excluding wind conditions in excess of specified speeds.

- Ambient conditions – what atmospheric conditions are assumed to be the base case (testing results will need to be adjusted to take into account any variance from these ambient conditions).

In addition, for wind farms with multiple wind turbine generators, the testing procedures must state those tests to be carried out on a per turbine basis and those on an average basis.

An example of the way a performance testing and liquidated damages regime can operate is best illustrated diagrammatically. Refer to the flowchart in Appendix 2 to see how the various parts of the performance testing regime should interface.

KEY GENERAL CLAUSES IN EPC CONTRACTS

Delay and Extensions of Time

(a) The Prevention Principle

As noted previously, one of the advantages of an EPC contract is that it provides the project company with a fixed completion date. If the contractor fails to complete the works by the required date they are liable for DLDs. However, in some circumstances the contractor is entitled to an extension of the date for completion. Failure to grant an extension for a project company caused delay can void the liquidated damages regime and "set time at large". This means the contractor is only obliged to complete the works within a reasonable time.

This is the situation under common law governed contracts due to the prevention principle. The prevention principle was developed by the courts to prevent employers ie project companies from delaying contractors and then claiming DLDs.

The legal basis of the prevention principle is unclear and it is uncertain whether you can contract out of the prevention principle. Logically, given most commentators believe the prevention principle is an equitable principle, explicit words in a contract should be able to override the principle. However, the courts have tended to apply the prevention principle even in circumstances where it would not, on the face of it, appear to apply. Therefore, there is a certain amount of risk involved in trying to contract out of the prevention principle. The more prudent and common approach is to accept the existence of the prevention principle and provide for it the EPC contract.

The contractor?s entitlement to an extension of time is not absolute. It is possible to limit the contractor?s rights and impose pre-conditions on the ability of the contractor to claim an extension of time. A relatively standard Extension of Time (EOT) clause would entitle the contractor to an EOT for:

- An act, omission, breach or default of the project company

- Suspension of the works by the project company (except where the suspension is due to an act or omission of the contractor)

- A variation (except where the variation is due to an act or omission of the contractor)

- Force majeure

Which cause a delay on the critical path 34 and about which the contractor has given notice within the period specified in the contract. It is permissible (and advisable) from the project company?s perspective to make both the necessity for the delay to impact the critical path and the obligation to give notice of a claim for an extension of time conditions precedent to the contractor?s entitlement to receive an EOT. In addition, it is usually good practice to include a general right for the project company to grant an EOT at any time. However, this type of provision must be carefully drafted because some judges have held (especially when the project company?s representative is an independent third party) the inclusion of this clause imposes a mandatory obligation on the project company to grant an extension of time whenever it is fair and reasonable to do so, regardless of the strict contractual requirements. Accordingly, from the project company?s perspective it must be made clear that the project company has complete and absolute discretion to grant an EOT, and that it is not required to exercise its discretion for the benefit of the contractor.

Similarly, following some recent common law decisions, the contractor should warrant that it will comply with the notice provisions that are conditions precedent to its right to be granted an EOT.

We recommend using the clause in Part II of Appendix 1.

(b) Concurrent Delay

You will note that in the suggested EOT clause, one of the subclauses refers to concurrent delays. This is relatively unusual because most EPC contracts are silent on this issue. For the reasons explained below we do not agree with that approach.

A concurrent delay occurs when two or more causes of delay overlap. It is important to note that it is the overlapping of the causes of the delays not the overlapping of the delays themselves. In our experience, this distinction is often not made. This leads to confusion and sometimes disputes. More problematic is when the contract is silent on the issue of concurrent delay and the parties assume the silence operates to their benefit. As a result of conflicting case law it is difficult to determine who, in a particular fact scenario, is correct. This can also lead to protracted disputes and outcomes contrary to the intention of the parties.

There are a number of different causes of delay which may overlap with delay caused by the contractor. The most obvious causes are the acts or omissions of a project company.

A project company often has obligations to provide certain materials or infrastructure to enable the contractor to complete the works. The timing for the provision of that material or infrastructure (and the consequences for failing to provide it) can be affected by a concurrent delay.

For example, the project company is usually obliged, as between the project company and the contractor, to provide a transmission line to connect to the wind farm by the time the contractor is ready to commission the wind farm. Given the construction of the transmission line can be expensive, the project company is likely to want to incur that expense as close as possible to the date commissioning is due to commence. For this reason, if the contractor is in delay the project company is likely to further delay incurring the expense of building the transmission line. In the absence of a concurrent delay clause, this action by the project company, in response to the contractor?s delay, could entitle the contractor to an extension of time.

Concurrent delay is dealt with differently in the various international standard forms of contract. Accordingly, it is not possible to argue that one approach is definitely right and one is definitely wrong. In fact, the right? approach will depend on which side of the table you are sitting.

In general, there are three main approaches for dealing with the issue of concurrent delay. These are:

- Option One – the contractor has no entitlement to an extension of time if a concurrent delay occurs.

- Option Two – the contractor has an entitlement to an extension of time if a concurrent delay occurs.

- Option Three – the causes of delay are apportioned between the parties and the contractor receives an extension of time equal to the apportionment. For example, if the causes of a 10-day-delay are apportioned 60:40 project company : contractor, the contractor would receive a six-day extension of time.

Each of these approaches is discussed in more detail below.

(i) Option One: Contractor not entitled to an extension of time for concurrent delays.

A common, project company friendly, concurrent delay clause for this option one is:

"If more than one event causes concurrent delays and the cause of at least one of those events, but not all of them, is a cause of delay which would not entitle the Contractor to an extension of time under [EOT Clause], then to the extent of the concurrency, the Contractor will not be entitled to an extension of time."

The most relevant words are bolded.

Nothing in the clause prevents the contractor from claiming an extension of time under the general extension of time clause. What the clause does do is to remove the contractor?s entitlement to an extension of time when there are two or more causes of delay and at least one of those causes would not entitle the contractor to an extension of time under the general extension of time clause.

For example, if the contractor?s personnel were on strike and during that strike the project company failed to approve drawings, in accordance with the contractual procedures, the contractor would not be entitled to an extension of time for the delay caused by the project company?s failure to approve the drawings.

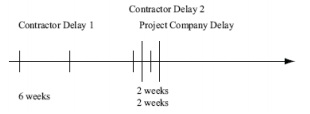

The operation of this clause is best illustrated diagrammatically.

Example 1: Contractor not entitled to an extension of time for project company caused delay

In this example, the contractor would not be entitled to any extension of time because the Contractor Delay 2 overlap entirely the Project Company Delay. Therefore, using the example clause above, the contractor is not entitled to an extension of time to the extent of the concurrency. As a result, at the end of the Contractor Delay 2 the contractor would be in eightweek delay (assuming the contractor has not, at its own cost and expense accelerated the works).

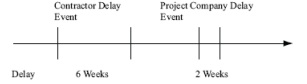

Example 2: Contractor entitled to an extension of time for project company-caused delay

In this example, there is no overlap between the contractor and project company delay events and the contractor would be entitled to a two-week extension of time for the project company delay. Therefore, at the end of the project company delay the contractor will remain in six weeks delay, assuming no acceleration.

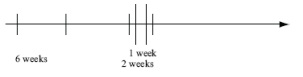

Example 3: Contractor entitled to an extension of time for a portion of the project company caused delay

In this example, the contractor would be entitled to a one week extension of time because the delays overlap for one week. Therefore, the contractor is entitled to an extension of time for the period when they do not overlap, ie when the extent of the concurrency is zero. As a result, after receiving the one-week extension of time, the contractor would be in seven weeks delay, assuming no acceleration.

From a project company?s perspective, we believe, this option is both logical and fair. For example, if, in example 2 the project company delay was a delay in the approval of drawings and the contractor delay was the entire workforce being on strike, what logic is there in the contractor receiving an extension of time? The delay in approving drawings does not actually delay the works because the contractor could not have used the drawings given its workforce was on strike. In this example, the contractor would suffer no detriment from not receiving an extension of time. However, if the contractor did receive an extension of time it would effectively receive a windfall gain.

The greater number of obligations the project company has the more reluctant the contractor will likely be to accept option one. Therefore, it may not be appropriate for all projects.

(ii) Option Two: Contractor entitled to an extension of time for concurrent delays

Option two is the opposite of option one and is the position in many of the contractor friendly standard forms of contract. These contracts also commonly include extension of time provisions to the effect that the contractor is entitled to an extension of time for any cause beyond its reasonable control which, in effect, means there is no need for a concurrent delay clause.

The suitability of this option will obviously depend on which side of the table you are sitting. This option is less common than option one but is nonetheless sometimes adopted. It is especially common when the contractor has a superior bargaining position.

(iii) Option Three: Responsibility for concurrent delays is apportioned between the parties

Option three is a middle ground position that has been adopted in some of the standard form contracts. For example, the Australian Standards construction contract AS4000 adopts the apportionment approach. The AS4000 clause states:

"34.4 Assessment

When both non qualifying and qualifying causes of delay overlap, the Superintendent shall apportion the resulting delay to WUC according to the respective causes' contribution.

In assessing each EOT the Superintendent shall disregard questions of whether:

- WUC can nevertheless reach practical completion without an EOT; or

- the Contractor can accelerate, but shall have regard to what prevention and mitigation of the delay has not been effected by the Contractor."

We appreciate the intention behind the clause and the desire for both parties to share responsibility for the delays they cause. However, we have some concerns about this clause and the practicality of the apportionment approach in general. It is easiest to demonstrate our concerns with an extreme example. For example, what if the qualifying cause of delay was the project company?s inability to provide access to the site and the nonqualifying cause of delay was the contractor?s inability to commence the works because it had been black banned by the unions. How should the causes be apportioned? In this example, the two causes are both 100% responsible for the delay.

In our view, an example like the above where both parties are at fault has two possible outcomes. Either:

- The delay is split down the middle and the contractor receives 50% of the delay as an extension of time; or

- The delay is apportioned 100% to the project company and therefore the contractor receives 100% of the time claimed. The delay is unlikely to be apportioned 100% to the contractor because a judge or arbitrator will likely feel that that is "unfair", especially if there is a potential for significant liquidated damages liability. We appreciate the above is not particularly rigorous legal reasoning, however, the clause does not lend itself to rigorous analysis.

In addition, option three is only likely to be suitable if the party undertaking the apportionment is independent from both the project company and the contractor.

Exclusive remedies and fail safe clauses

It is common for contractors to request the inclusion of an exclusive remedies clause in an EPC contract. However, from the perspective of a project company, the danger of an exclusive remedies clause is that it prevents the project company from recovering any type of damages not specifically provided for in the EPC contract.

An EPC contract is conclusive evidence of the agreement between the parties to that contract. If a party clearly and unambiguously agrees that their only remedies are those within the EPC contract, they will be bound by those terms. However, the courts have been reluctant to come to this conclusion without clear evidence of an intention of the parties to the EPC contract to contract out of their legal rights. This means if the common law right to sue for breach of EPC contract is to be contractually removed, it must be done by very clear words.

© DLA Piper

This publication is intended as a general overview and discussion of the subjects dealt with. It is not intended to be, and should not used as, a substitute for taking legal advice in any specific situation. DLA Piper Australia will accept no responsibility for any actions taken or not taken on the basis of this publication.

DLA Piper Australia is part of DLA Piper, a global law firm, operating through various separate and distinct legal entities. For further information, please refer to www.dlapiper.com