INTRODUCTION

Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) contracts are the most common form of contract used to undertake construction works by the private sector on large-scale and complex infrastructure projects 1 . Under an EPC contract, a contractor is obliged to deliver a complete facility to a developer who need only "turn a key" to start operating the facility, hence EPC contracts are sometimes called turnkey construction contracts. In addition to delivering a complete facility, the contractor must deliver that facility for a guaranteed price by a guaranteed date and it must perform to the specified level. Failure to comply with any requirements will usually result in the contractor incurring monetary liabilities.

It is timely to examine EPC contracts and their use on infrastructure projects given the bad publicity they have received, particularly in contracting circles. A number of contractors have suffered heavy losses and, as a result, a number of contractors now refuse to enter into EPC contracts in certain jurisdictions. This problem has been exacerbated by a substantial tightening in the insurance market. Construction insurance has become more expensive due to significant losses suffered on many projects.

However, because of their flexibility, the value and the certainty sponsors and lenders derive from EPC contracts, and the growing popularity of Public Private Partnership (PPP) 2 projects, the authors believe EPC contracts will continue to be the predominant form of construction contract used on large-scale infrastructure projects in most jurisdictions 3 .

This paper will only focus on the use of EPC contracts in the wind power sector. However, the majority of the issues raised are applicable to EPC contracts used in all sectors.

Prior to examining renewable energy power project EPC contracts in detail, it is useful explore the basic features of a wind farm project.

OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT STATE OF RENEWABLE ENERGY IN AUSTRALIA

Current uptake

Renewable energy projects range from solar, wind, hydro, wave, tidal, geothermal and nuclear production. Wind energy is currently one of the most economically feasible forms of renewable energy in many countries.

Renewable energy sources contributed 9.6% of the total electricity produced in Australia in the year to September 2011, up from 8.7% in 2010 4 . Of this amount, approximately two-thirds (67.2%) was generated by hydro-electricity. Wind energy was the next largest source, contributing 21.9%, followed by bioenergy (8.5%) and solar PV (2.3%).

Renewable energy policy and legislative framework - federal

The federal regulatory framework governing the renewable sector is set out in the Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000 (Cth) (Act), which came into effect in April 2001. This Act boosted the wind energy industry in Australia by introducing the Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET), which set a target for renewable energy generation from eligible renewable energy power stations in Australia of 9,500 GWh by 2010. The aim of the MRET was both to encourage additional generation of electricity from existing renewable energy power stations and to encourage new renewable energy projects.

In August 2009, the Federal Government implemented the Renewable Energy Target (RET) scheme. The expanded RET increased the previous MRET by more than four times, with a new renewable energy generation target of 45,000 GWh by 2020, representing a target of 20% of Australia's electricity being supplied by renewable sources by 2020 and to be maintained at this level until 2030 5 . At the end of 2010, the generating capacity of renewable power stations was approximately 12,200 GWh of eligible renewable energy per year 6 .

The MRET and RET created a guaranteed market for additional renewable energy deployment using a mechanism of tradable Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs). RECs are market-based instruments that are generated by accredited renewable energy power stations and can then be traded and sold. Demand for RECs is created by a legal obligation that is placed on parties who buy wholesale electricity (retailers and large users of electricity) to purchase and surrender a certain amount of RECs each year.

During the early years of the expanded RET scheme in 2009 and 2010, strong demand for small-scale renewable technologies including solar hot water panels and heat pumps meant that an increasingly large number of RECs were entering the market from small-scale technologies. This lead to some volatility in the market and depressing of REC prices, which caused investment uncertainties and potential delays for large-scale renewable energy projects 7 .

In June 2010, Federal Parliament passed legislation 8 to split the RET into two parts - the Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET) with Large-Scale Generation Certificates (LGCs) and the Small-Scale Renewable Energy Scheme (SRES) with Small-Scale Technology Certificates (STCs). The LRET covers large scale renewable energy projects including wind farms, commercial solar and geothermal, whereas the SRES covers small-scale technologies such as solar panels and solar hot water systems.

It is intended that the majority of the RET will be delivered by

large-scale renewable energy projects under the LRET. The LRET

includes legislative annual targets, starting at 10,000 GWh in 2011

and increasing to 41,000 GWh in 2020 and remaining at that level

until 2030 9 .

There are no annual targets for the SRES.

Under the LRET, accredited renewable energy power stations may be entitled to create one LGC for each MWh of electricity generated 10 , which can then be sold and transferred to liable entities using the REC Registry. Power stations using at least one of the more than 15 types of "eligible renewable energy sources" (listed in s.17(1) of the Act), which includes wind energy, can become accredited. LGCs can only be created for renewable energy source that is new or additional to the "baseline" amount of renewable source energy generated by that power station before the Act came into effect. Each accredited power station must submit an annual Electricity Generation Return to the Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator (ORER).

Under the SRES, owners of small-scale technology will receive one STC for each MWh generated by the smallscale system or displaced by the installation of a solar hot water heater or heat pump.

Under the amended RET, liable entities will be required to purchase and surrender an amount of both LGCs and STCs. The amount of LGCs and STCs to be purchased is determined by the Renewable Power Percentage (RPP) and Small-Scale Technology Percentage (STP), respectively. Liable entities are required to purchase LGCs and STCs and surrender them to the ORER on an annual basis (for LGCs) and a quarterly basis (for STCs). Liable entitles may purchase LGCs directly from renewable energy power stations or from agents dealing in LGCs. The market price of LGCs is dependent on supply and demand and has varied between $10 and $60 in the past 11 . Liable entities may purchase their STCs through an agent who deals with STCs or through the STC Clearing House. There is a government-guaranteed price of $40/STC using the STC clearing house, although the price may be less than $40 in the market. If a liable entity does not meet its requirements, it must pay a "shortfall charge", currently set at $65 per LGC or STC not surrendered.

The aim of the reforms is to allow the market to set a REC price for large-scale renewables that will provide incentives for those projects. As the increasing obligation of liable entities to purchase LRECs to 2020 increases demand, LREC prices are expected to increase, which is in turn expected to support the investment and expansion of large-scale renewable generation.

Other federal legislative and policy frameworks that impact on renewable energy development are environmental regulations under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth); and the carbon price mechanism under the Clean Energy Act 2011 (Cth) (CE Act) and associated policies under the Clean Energy Plan 2011 (Clean Energy Plan) 12 , which are discussed in further detail below.

Renewable energy policy and legislative framework - state

State-based planning systems and associated guidelines will also impact upon aspects of renewable energy development such as the siting of wind farms and their design.

For example, in Victoria, the Policy and Planning Guidelines for Development of Wind Energy Facilities in Victoria (August 2011) 13 (guidelines) set out guidance relating to where a wind energy facility can be constructed in accordance with the state planning framework and the matters that local governments must take into account in assessing wind energy facility proposals. Under the guidelines, wind turbines are excluded from (among other places) listed geographical areas (including the Yarra Valley, Dandenong Ranges, Bellarine and Mornington Peninsulas) and will not be permitted to be built within two kilometres of an existing dwelling without the written consent of the owner of the dwelling.

Carbon price mechanism and the Clean Energy Plan

The CE Act and the 21 bills of the Clean Energy Future Legislative Package were passed by the Federal Government in 2011 and are scheduled to commence in April 2012. The key feature of the CE Act is the introduction of a Carbon Price Mechanism (CPM) from 1 July 2012. Under the CPM, liable businesses will be required to purchase and surrender to the Federal Government a permit for every tonne of covered greenhouse gas emissions produced. The price of permits will be fixed for the first three years and then, from 1 July 2015 onwards, the price of permits will be set by the market and the number of permits issued by the Federal Government will be capped. We have a paper that sets out the details of the CPM in greater detail - please let us know if you would like a copy.

Although the renewable energy industry will not be directly impacted by the CPM, the effect of putting a price on carbon will provide an economic driver to incentivise investment in renewable energy technologies. Modelling undertaken by the Australian Treasury indicates that under moderate carbon price scenarios, carbon pricing is unlikely to quickly force out many existing generators, although it may speed the planned retirements of marginal units. However, the Australian Treasury has indicated that the impact of a carbon price would be more likely to influence the choice of new capacity and to transform the Australian electricity sector as growth in energy demand brings on new clean energy capacity 14 . The Federal Government has also indicated that, in the future, it anticipates that the CPM will be the principal clean energy deployment incentive mechanism, with the RET acting as transitional support in the interim 15 .

In addition to the CPM, other policy measures in the Clean Energy Plan announced by the Federal Government in July 2011 to facilitate the development of renewable energy include:

- The creation of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), a new body to facilitate and coordinate up to $10 billion of investment in the areas of renewable energy, enabling technologies, energy efficiency and lowemissions technologies. The aim of the CEFC is to unlock significant new private sector investment by providing equity investments, commercial loans and loan guarantees, with equity to be reinvested in the CEFC.

- The creation of the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, an independent statutory body responsible for managing $3.2 billion in funds that have or will be allocated to existing government grants programmes that support the development of renewable energy technologies.

BASIC FEATURES OF A WIND FARM PROJECT

Wind farm projects

A wind farm typically comprises a series of wind turbines, a substation, cabling (to connect the wind turbines and substation to the electricity grid), wind monitoring equipment and temporary and permanent access tracks. The wind turbines used in commercial wind farms are generally large slowly rotating, three bladed machines that typically produce between 1MW and 2MW of output. Each wind turbine is comprised of a rotor, nacelle, tower and footings. The height of a tower varies with the size of the generator but can be as high as 100m. The number of turbines depends on the location and capacity of turbines.

The amount of power a wind generator can produce is dependent on the availability and the speed of the wind. The term "capacity factor" is used to describe the actual output of a wind energy facility as the percentage of time it would be operating at maximum power output. For every megawatt hour (MWh) of renewable energy generated, the emission of approximately 1.3 tonnes of carbon dioxide through coal-fired electricity generation is displaced 16 .

Wind farms need to be located on sites that have strong, steady winds throughout the year, good road access and proximity to the electricity grid. Australia has one of the world?s best wind resources, especially along the southeast coast of the continent and in Tasmania.

According to the Clean Energy Council, the average prices of turbine supply contracts fell by up to 20% during 2011 17 . The Clean Energy Council's 18 estimated indicative direct costs of the various components of a wind farm, in terms of their percentage contribution to the overall capital cost of the project, are:

- Turbine works - 60-75%

- Civil and electrical works to the point of connection - 10-25%

- Grid connection - 5-15%

- Development and consulting work, including wind speed monitoring - 5-15%.

THE CONTRACTUAL STRUCTURE

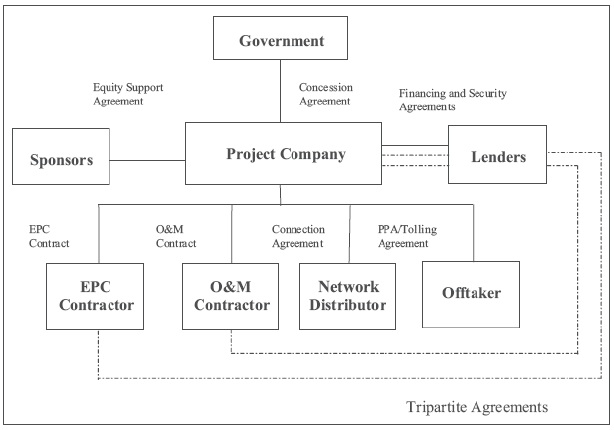

The diagram below illustrates the basic contractual structure of a project financed wind farm project using an EPC contract.

The detailed contractual structure will vary from project to project. However, for the purpose of this paper we have examined a project with the basic structure illustrated above. We do note that some wind farm projects split the EPC into a Wind Turbine Generator (WTG) supply contract and a Balance of Plant (BOP) contract, where the performance guarantee element is dealt with in a Warranty Operating and Maintenance Agreement (WOM). The principles are essentially the same as set out below and we will discuss specific components later in this paper. The WOM is the subject of a separate paper - please let us know if you would like a copy of this paper.

As can be seen from the diagram, the project company 19 will usually enter into agreements that cover the following elements:

- An agreement that gives the project company the right to construct and operate the wind farm and sell electricity generated by the wind farm. Traditionally this was a concession agreement (or project agreement) with a relevant government entity granting the project company a concession to build and operate the wind farm for a fixed period of time (usually between 15 and 25 years), after which it was handed back to the government. This is why these projects are sometimes referred to as Build Operate Transfer or Build Own Operate Transfer projects20.

-

However, following the deregulation of electricity industries in many countries, merchant wind farms are now being constructed. A merchant power project is a project that sells electricity into an electricity market and takes the market price for that electricity. Merchant power projects do not normally require an agreement between the project company and a government entity to be constructed. Instead, they need simply obtain the necessary planning, environmental and building approvals. The nature and extent of these approvals will vary from place to place. In addition, the project company will need to obtain the necessary approvals and licences to sell electricity into the market.

- In traditional project financed power projects (as opposed to merchant power projects) there is a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between the project company and the local government authority, where the local government authority undertakes to pay for a set amount of electricity every year of the concession, subject to availability, regardless of whether it actually takes that amount of electricity (referred to as a "take or pay" obligation). In turn, the project company will undertake to produce a minimum quantity of electricity and LGCs. Sometimes a tolling agreement is used instead of a PPA. A tolling agreement is an agreement under which the power purchaser directs how the plant is to be operated and despatched. In addition, the power purchaser is responsible for the provision of fuel. This eliminates one risk variable (for the project company) but also limits its operational flexibility.

-

In the absence of a PPA, project companies developing a merchant power plant, and lenders, do not have the same certainty of cash flow as they would if there was a PPA. Therefore, merchant power projects are generally considered higher risk than non-merchant projects 21 . This risk can be mitigated by entering into hedge agreements. Project companies developing merchant power projects often enter into synthetic PPAs or hedge agreements to provide some certainty of revenue. These agreements are financial hedges as opposed to physical sales contracts. Their impact on the EPC contract is discussed in more detail below.

- A connection agreement for connection of the wind farm generation equipment into the relevant electricity distribution network (network) between the project company and the owner of the network, which is either a transmission company, a distribution company, an electrical utility or a small grid owner/operator. The connection agreement will broadly cover the construction and installation of connection facilities by the owner of the network and the terms and conditions by which electricity is to be delivered to the generation equipment at the wind farm from the network (import electricity) and delivered into the network once generated by the wind farm (export electricity).

- A construction contract governing various elements of the construction of the wind farm from manufacture of the blades and towers and assembly of the nacelles and hubs and construction of the balance of the plant comprising civil and electrical works. There are a number of contractual approaches that can be taken to construct a wind farm. An EPC contract is one approach. Another option is to have a supply contract for the wind turbines, a design agreement and construction contract with or without a project management agreement. The choice of contracting approach will depend on a number of factors including the time available, the lender requirements and the identity of the contractor(s). The major advantage of the EPC contract over the other possible approaches is that it provides for a single point of responsibility. This is discussed in more detail below.

-

Interestingly, on large project financed projects the contractor is increasingly becoming one of the sponsors, ie an equity participant in the project company. Contractors will ordinarily sell down their interest after financial close because, generally speaking, contractors will not wish to tie up their capital in operating projects. In addition, once construction is complete the rationale for having the contractor included in the ownership consortium no longer exists. Similarly, once construction is complete a project will normally be reviewed as lower risk than a project in construction, therefore, all other things being equal, the contractor should achieve a good return on its investments.

In our experience most projects and almost all large private sector wind farms use an EPC contract.

- An agreement governing the operation and maintenance of the wind farm. This is usually a longterm Operating and Maintenance Agreement (O&M agreement) with an operator for the operation and maintenance of the wind farm. The term of the O&M agreement will vary from project to project. The operator will usually be a sponsor especially if one of the sponsors is an Independent Power Producer (IPP)or utility company whose main business is operating wind farms. Therefore, the term of the O&M agreement will likely match the term of the concession agreement or the PPA. In some financing structures the lenders will require the project company itself to operate the facility. In those circumstances the O&M contract will be replaced with a technical services agreement, under which the project company is supplied with the know-how necessary for its own employees to operate the facility. In other circumstances the project company will enter into a fixed short-term O&M agreement with the manufacturer and supplier of the major equipment supplied, for example, in the case of a wind farm, the wind turbine generators, during which the appointed operator will train the staff of the project company. The project company will take over operation of the wind farm on expiry of the O&M agreement and will perform all functions of the operator save for some support functions being retained by the manufacturer.

- Financing and security agreements with the lenders to finance the development of the project.

Accordingly, the construction contract is only one of a suite of documents on a wind farm project. Importantly, the project company operates the project and earns revenues under contracts other than the construction contract. Therefore, the construction contract must, where practical, be tailored so as to be consistent with the requirements of the other project documents. This is even more relevant when the EPC structure is split into WTG supply, BOP and WOM elements.

As a result, it is vital to properly manage the interfaces between the various types of agreements. These interface issues are discussed in more detail later.

Footnotes

1 By this we mean industry sectors including

power, oil and gas, transport, water and telecommunications.

2 The terms Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) and

Public Private Partnerships (PPP) are used interchangeably. Sectors

which undertake PFI projects include prisons, schools, hospitals,

universities and defence.

3 Some jurisdictions, such as the USA, use alternative

structures which separate the work into various components.

Governments in Asia have traditionally used other forms of

contracts to undertake large scale infrastructure projects. For

example, the Hong Kong Government routinely uses Bills of

Quantities as opposed to D&C or EPC contracts.

4 Clean Energy Council, Clean Energy Australia Report

2011

http://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/cec/resourcecentre/reports/cleane

nergyaustralia ; Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism, Draft

Australian Energy White Paper 2011

http://www.ret.gov.au/energy/facts/white_paper/draft-ewp-

2011/Pages/Draft-Energy-White-Paper-2011.aspx .

5 Explanatory Memorandum to the Renewable Energy

(Electricity) Amendment Bill 2010 (Cth), p4.

6 Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator, Increasing

Australia's renewable electricity generation,

www.orer.gov.au

7 Media Release by Senator Penny Wong, Enhanced

Renewable Energy Target Scheme, 26 February 2010

http://www.climatechange.gov.au/minister/previous/wong/2010/mediareleases/February/mr20100226.aspx.

8 Legislative package including the Renewable Energy

(Electricity) Amendment Bill 2010 (Cth).

9 Under section 40(1) of the Act.

10 Under s. 18 of the Act, a LGC may be created by a

nominated person in respect of an accredited power station for each

whole MWh of electricity generated by the power station during a

year that is in excess of the power station's 1997 eligible

renewable power baseline. A nominated person for an accredited

power station is the person who made the application for

accreditation or a person who has been granted an approval under

section 30B of the Act in relation to the power station. Under

section 30B a registered person who is a stakeholder in relation to

an accredited power station may apply to the Regulator for approval

to become the nominated person for the power station. A stakeholder

is defined under the Act as a person who operates the power station

or who owns all or a part of the power station (whether alone or

together with one or more other persons). An application for

changing the nominated person in accordance with section 30B must

(among other things) be accompanied by a statement in writing from

each other stakeholder in relation to the power station indicating

that the other stakeholder agrees to the making of the application

(section 30B(2)(e)). In addition to the legislative framework, it

is prudent to set out in any operating and maintenance agreement a

provision that clearly states that owner is entitled to all energy,

revenues and other entitlements including LGCs under the Act that

is generated by the wind farm during the term of the

agreement.

11 Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator, Increasing

Australia's renewable electricity generation,

www.orer.gov.au

12 The Clean Energy Future Package is available at:

(http://www.cleanenergyfuture.gov.au/clean-energy-future/our-plan/

13 Available online at:

http://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/77851/Policyand-planning-guidelines-for-development-of-wind-energy-facilities-inVictoria.pdf

14 Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism, Draft

Australian Energy White Paper 2011,

http://www.ret.gov.au/energy/facts/white_paper/draft-ewp-

2011/Pages/Draft-Energy-White-Paper-2011.aspx p.41

15 Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism, Draft

Australian Energy White Paper 2011,

http://www.ret.gov.au/energy/facts/white_paper/draft-ewp-

2011/Pages/Draft-Energy-White-Paper-2011.aspx, pp215-216)

16 McLennan Magasanik Associates Pty Ltd , Report to

sustainability Victoria - Assessment of greenhouse gas abatement

from wind farms in Victoria (June 2006)

http://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/resources/documents/Greenhouse_a

batement_from_wind_report.pdf

17 (Clean Energy Australia Report 2011, p.54)

18 (Clean Energy Australia Report 2011, p.54)

19 Given this paper focuses on project financed

infrastructure projects we refer to the employer as the project

company. Whilst project companies are usually limited liability

companies incorporated in the same jurisdiction as the project is

being developed in the actual structure of the project company will

vary from project to project and jurisdiction to

jurisdiction.

20 Power projects undertaken by the private sector, and

more particularly, by non-utility companies are also referred to as

IPPs, Independent Power Projects. They are undertaken by IPPs -

Independent Power Producers.

21 However, because merchant power projects are

generally undertaken in more sophisticated and mature markets there

is usually a lower level of country or political risk. Conversely,

given the move towards privatisation of electricity markets in

various Asian countries, this may no longer be the

case.

© DLA Piper

This publication is intended as a general overview and discussion of the subjects dealt with. It is not intended to be, and should not used as, a substitute for taking legal advice in any specific situation. DLA Piper Australia will accept no responsibility for any actions taken or not taken on the basis of this publication.

DLA Piper Australia is part of DLA Piper, a global law firm, operating through various separate and distinct legal entities. For further information, please refer to www.dlapiper.com