WIPO's annual "World IP Day" is 26 April 2021. This year's theme is "IP & SMEs: Taking your ideas to market". Now, in most developed countries, one could develop a compelling narrative around this. But it's slightly more complicated here in Australia, because the two don't mesh quite as they should. By this, I mean that it's SMEs that had a whole second tier patent system developed around them (Australia's "innovation patent"), it's SMEs that (allegedly) failed to make use of the system, and that it's (apparently) SMEs that are responsible for its abolition later this year. However, a quick peek under the bonnet suggests that much of this is political rhetoric and that despite the Government clearly thinking otherwise, SMEs are as IP-dependent here in Australia as they are anywhere in the world.

Innovation patents 101

From its introduction in 2001, the "innovation patent" has been held up as a symbol of the Australian Government's commitment to encouraging innovation amongst Australian SMEs.

The innovation patent is Australia's second-tier patent system. Novelty, written description and industrial applicability criteria are the same as for the first-tier "standard" patent system. However, in exchange for offering the public only an "innovative step" (a pseudo-novelty test requiring differences amounting to a "substantial contribution to the working of the invention"), a patentee is afforded only an 8-year term as opposed to the standard 20 years.

Proponents of the innovation patent system note that not all inventions are of the "Eureka" quantum leap variety befitting a standard patent. Rather, many are iterative – making slow but steady advances on what came before it. Others are in short lifecycle technologies such as televisions, smartphones and the like. The argument is that such iterative advances may be "obvious" for the purposes of a standard patent, but still invite substantial RD&E expenditure on a patentee's part – and so why shouldn't the patentee be compensated with some measure of monopoly right? To my mind, this seems fair – a patent system designed around Australia's iconic "backyard" or "garage" inventors.

Innovation patents are "granted" shortly upon filing (a potential problem in itself), but are not enforceable at law until such time as they have been "certified" (i.e., examined). However, once certified, the enforcement remedies available to a patentee are the same as those for a standard patent. For this reason, innovation patents – particularly innovation patents divided out from standard patent parents, can be effective "litigation weapons" because the low innovative step threshold makes them somewhat difficult to revoke in a counter-claim for invalidity (and suing against a divisional innovation patent will not expose the parent standard patent to a revocation cross-claim). Thus, innovation patents provide a legitimate strategic tool for those looking to enforce their Australian patent rights.

The innovation patent system is "dead man walking"

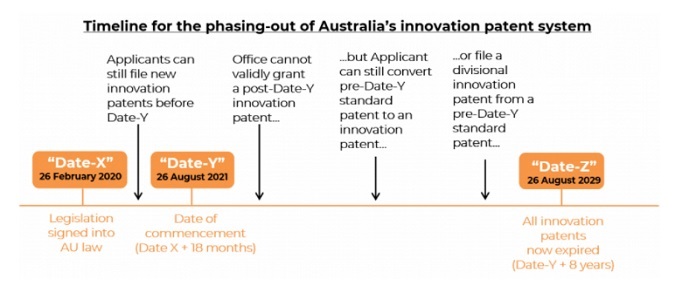

Following a lengthy review, the Australian Government has opted to phase out the innovation patent system from 26 August 2021. The transitional provisions are summarised below, but there are three principal dates of which applicants should be aware:

- The legislation was passed into law (i.e., received the required Royal Assent) on 26 February 2020. For the purposes of filing new innovation patents, the legislation takes effect from 26 August 2021, which is 18 months from the date of Royal Assent.

- At any time prior to 26 August 2021, new innovation patent applications can be filed. In other words, nothing changes until the legislation takes effect.

- As of 26 August 2021, no new innovation patent applications can be validly granted. However, an existing and pending standard patent application (i.e., having a filing date prior to 26 August 2021) can still be converted into an innovation patent, or can have a divisional innovation patent filed from it.

Why is the innovation patent being phased out?

The perceived "problem" with the innovation patent was three-fold.

- Firstly, there has been a perception that the threshold test for innovative step (essentially a pseudo-novelty test, as noted above) was too low and that this, in turn, may give rise to a proliferation of difficult-to-revoke certified innovation patents that were enforceable at law. However, this could be easily remedied by raising the threshold for an innovative step. That's strictly outside the scope of this article, so we might leave it for another day.

- Secondly, that the "granted upon filing" status rendered the system susceptible to abuses such as foreign applicants potentially being able to claim Government subsidies in their country of origin for obtaining a "granted" patent. Again, this has little to do with SMEs, but surely, seeing as pending standard patents have the status of "filed", perhaps non-certified innovation patents could be "pending", "pre-certification", awaiting examination", etc., – in short, anything other than the present misrepresentation of "granted".

- Thirdly – and most significantly in respect of this article – there had been a perception that local SMEs were not making use of the innovation patent system (and even if they were, they were not deriving tangible benefits from it).

Ultimately, it is the third perceived problem that has been considered terminal, and this is the reason why IP and SMEs are somewhat strange bedfellows in Australia at present.

Local SMEs were (allegedly) not making use of the system...

This appears to be the primary justification for abolishing the innovation patent system. A 2014 review conducted by ACIP (the Advisory Council on Intellectual Property) had recommended – somewhat surprisingly at the time, that the innovation patent system be abolished. Following a protracted review process stretching back to 2011, ACIP eventually concluded by way of economic modelling that the innovation patent system was not meeting its stated objectives. Such objectives, of course, were to stimulate innovation in Australian SMEs by providing easier, quicker and cheaper patent rights as well as an avenue to protect their lower level inventions.

Objectively, it appears that the data presented in the economic report may have been open to a number of interpretations, and that disproportionate weight may have been attributed to certain factors. For example, the fact that there are a relatively high proportion of self-filed innovation patent applications cloud the data relating to the calculated total regulatory cost of the system and the assessment of commercial success of innovation patent filing entities. This obviously has an effect on the concluded net economic impact, which appears to have been a major factor influencing the stand taken by ACIP. Notwithstanding, the Productivity Commission and the Australian Government have subsequently backed this position, which effectively meant the writing was on the wall for the innovation patent system.

...which meant that the innovation patent system was not meeting its stated objectives

In recommending the innovation patent system be abolished (and then acting on its own recommendation), the Government merely assumed the position of both the Productivity Commission and ACIP before it. Both had opined that the innovation patent system (as it stood) was unlikely to provide net benefits to the Australian community or to the SMEs who are the intended beneficiaries of the system. The Productivity Commission found that the majority of SMEs who use the innovation patent system do not obtain value from it and that the system imposes significant costs on third parties looking to navigate around thickets of low-level patents.

The Government noted that the innovation patent system was established with the express objective of stimulating innovation amongst Australian SMEs. Rather than "fix" the innovation patent system, the Government was of the opinion that more targeted assistance may better assist SMEs, while avoiding the broader costs imposed by the innovation patent system.

So, what's the Government doing to support SMEs protect their IP?

Along with initiatives to support SMEs introduced through the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA) and existing programs such as the R&D Tax incentive, the Government noted that it had already implemented a number of measures to support SMEs such as the IP Toolkit for Collaboration, Source IP, the Patent Analytics Hub and grants and advisory services for businesses in certain industry sectors looking to leverage their IP. Moreover, IP Australia has established an IP Counsellor to China, is trialling patent analytics services and is raising education and awareness of IP issues with local start-ups.

More recently, IP Australia has introduced its Portal for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which comprises sections aimed at helping SMEs navigate the maze that is IP.

What are we doing to assist SMEs?

Your innovation patent can still be filed up until 26 August 2021 and will run for the full eight-year term. Any SMEs thinking this path might be right for them should get in touch with their patent attorney as soon as possible.

Alternatively, or in combination with the Government resources mentioned above, many patent attorneys (such as us) are happy to point SMEs in the right direction, at no cost and with no obligation – after all, Mr Gates, Mr Musk and their mates all had to start somewhere...

Happy World IP Day, everyone.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.