- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- with readers working within the Advertising & Public Relations and Healthcare industries

1. What legislation applies to arbitration in your country? Are there any mandatory laws?

The legislation governing arbitration in the British Virgin Islands (the "BVI") is the Arbitration Act 2013 (the "Arbitration Act" or the "Act"). The Act came into force on 1 October 2014 and repealed the Arbitration Act 1976. The Arbitration Act established the BVI International Arbitration Centre (the "BVI IAC") which opened in 2016. The BVI IAC has issued its own rules, the BVI IAC Arbitration Rules (the "Rules") (see Question 6 below) which were updated last in 2021.

Part XI of the Act sets out the mandatory and nonmandatory provisions.

2. Is your country a signatory to the New York Convention? Are there any reservations to the general obligations of the Convention?

Yes, the United Kingdom extended the New York Convention to the BVI on 24 February 2014 which took effect on 25 May 2014. It appears that the United Kingdom did not extend the reciprocity reservation to the BVI.

3. What other arbitration-related treaties and conventions is your country a party to?

The United Kingdom extended the Arbitration (International Investment Disputes) Act 1966 to the BVI through the UK Arbitration (International Investment Disputes) Act (Application to Colonies, etc.) Order 1967 (SI 1967/159). This legislation governs the registration of awards under the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States, which established the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

On May 3, 2018, ICSID entered into an Agreement on General Arrangements with the BVI International Arbitration Centre ("BVI IAC"). The Agreement also encourages knowledge sharing between ICSID and BVI IAC and exchange of information and publications in the field of arbitration, conciliation, and other alternative methods of dispute resolution.

Other cooperation agreements include1:

- The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

- The Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC),

- ArbitralWomen;

- The Chartered Institute of Arbitrators.

4. Is the law governing international arbitration in your country based on the UNCITRAL Model Law? Are there significant differences between the two?

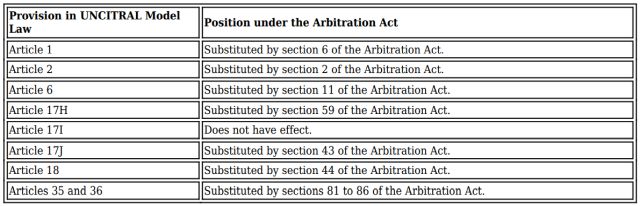

The Arbitration Act is based on the UNCITRAL Model Law subject to certain modifications and supplements expressly provided for in the Act as set out in the table below:

5. Are there any impending plans to reform the arbitration laws in your country?

There are no impending plans to reform the arbitration laws in the BVI at present. The Arbitration Act was last amended by the Arbitration (Amendment) Act 2020. Updated Arbitration Rules came into force on 16 November 2021.

6. What arbitral institutions (if any) exist in your country? When were their rules last amended? Are any amendments being considered?

The BVI IAC is the arbitral institution in the BVI. The Rules were originally issued in 2016 but have been comprehensively updated, with the most recent version, known as the Rules, coming into force on 16 November 2021. The Rules include new provisions for emergency arbitrator proceedings, expedited procedures, tribunal secretaries, joinder and consolidation, provisions for the use of remote hearing platforms and the electronic filing of submissions.

7. Is there a specialist arbitration court in your country?

There is no specialist arbitration court in the BVI. However, the BVI Commercial Court, a division of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, includes a dedicated bench for complex commercial disputes, including those involving arbitration.

8. What are the validity requirements for an arbitration agreement under the laws of your country?

Section 17 of the Arbitration Act requires that arbitration agreements be in writing, reflecting Article 7 of the UNCITRAL Model Law. This section defines an arbitration agreement as an agreement to submit all or specific disputes arising from a legal relationship to arbitration. The agreement can be part of a contract or a separate document. It will still be considered "in writing" if it is recorded in a document, even if unsigned or orally made but later documented. Arbitration agreements remain enforceable unless deemed null, inoperable, or incapable of performance, and termination of the underlying contract does not invalidate the arbitration clause.

9. Are arbitration clauses considered separable from the main contract?

Arbitration clauses within a contract are regarded as independent from the other contractual terms, following the separability principle (under section 32 of the Act, based on Article 16 of the Model Law). Practically, this means that if an arbitral tribunal finds the main contract null and void, the arbitration clause itself remains legally valid.

10. Do the courts of your country apply a validation principle under which an arbitration agreement should be considered valid and enforceable if it would be so considered under at least one of the national laws potentially applicable to it?

While BVI courts do not explicitly adopt a formal "validation principle"—the notion that an arbitration agreement should be deemed valid if enforceable under at least one applicable national law—the BVI's arbitration framework is arbitration-friendly.

Section 7 of the Act broadly defines "in writing," signalling a tendency to uphold arbitration agreements whenever feasible. Section 18, which mirrors article 8 of the Model Law, mandates that courts refer parties to arbitration unless the agreement is "null and void, inoperative, or incapable of being performed," establishing a high threshold for invalidating such agreements. Additionally, the New York Convention, which the BVI follows, reinforces this by permitting non-enforcement of arbitration agreements only under limited circumstances. The cumulative effect of these provisions, alongside international conventions, suggests that BVI courts favour enforcement of arbitration agreements, often applying an approach similar to the validation principle to ensure agreements are upheld when possible.

11. Is there anything particular to note in your jurisdiction with regard to multi-party or multicontract arbitration?

Paragraph 2 of Schedule 2 of the Act is an opt-in provision allowing the court, on the application of any party, to consolidate two or more arbitral proceedings if: (i) there is a common question of law or fact; (ii) the claims arise from the same transaction(s); or (iii) consolidation is desirable for other reasons. The court can order consolidation on just terms, direct hearings to occur simultaneously or consecutively, and stay proceedings if necessary. It can also issue directions on costs and appoint arbitrators if parties agree, or if they cannot agree, the court will appoint one. Article 33 of the Rules outlines the consolidation process.

12. In what instances can third parties or nonsignatories be bound by an arbitration agreement? Are there any recent court decisions on these issues?

Arbitration is inherently consensual, i.e., only those who have agreed to an arbitration agreement are bound by it. Consequently, an arbitral tribunal's jurisdiction is limited to disputes between the parties to that agreement and only to the extent outlined within it. In general, an arbitration agreement and any resulting award are enforceable only against the parties involved, unless third parties expressly agree to be bound. However, English case law, which holds persuasive authority in the BVI, suggests that in certain cases, an award might support a claim for indemnity against a third party.

Article 32 of the Rules allows for the joinder of additional parties to the arbitration upon request by any party, either before or after the tribunal is formed. The Arbitration Committee, after hearing all involved parties and considering relevant factors under article 32, may permit additional parties to join the proceedings.

13. Are any types of dispute considered nonarbitrable? Has there been any evolution in this regard in recent years?

The BVI Arbitration Act and Rules do not specify which matters are arbitrable, so common law principles govern arbitrability. BVI courts have examined whether specific proceedings—such as applications to appoint liquidators or claims of unfairly prejudicial conduct by minority shareholders—fall under the BVI courts' exclusive jurisdiction or are capable of arbitration. In Sian Participation Corp (in liquidation) v Halimeda International Ltd [2024] UKPC 16, the Privy Council clarified that arbitration agreements generally require disputes to be referred to arbitration. However, liquidation applications do not trigger the mandatory stay provisions under section 18 of the BVI Arbitration Act 2013, as they are not aimed at resolving claims about debt existence or amount.

Liquidation proceedings are distinct from typical dispute resolution because they do not aim to resolve specific claims; rather, they address the company's insolvency. Thus, presenting a liquidation application does not breach any arbitration agreement. The Privy Council upheld BVI's pro-arbitration stance, stating that arbitration remains the preferred route for dispute resolution if there is a genuine dispute over debt, which should be resolved through arbitration or a court judgment before liquidation proceedings are pursued. This decision supports arbitration, as it reassures parties that arbitration clauses do not hinder liquidation proceedings where no genuine debt dispute exists.

14. Are there any recent court decisions in your country concerning the choice of law applicable to an arbitration agreement where no such law has been specified by the Parties?

Article 40 of the Rules allows the arbitral tribunal to apply the rules of law designated by the parties, in line with respecting their agreement to arbitrate. However, if no law is specified, the tribunal is tasked with determining the appropriate law. In doing so, it would likely follow the guidance from the UK Supreme Court in Enka Insaat Ve Sanayi AS v OOO Insurance Company Chubb [2020] EWCA Civ 574, which outlined a framework for determining the applicable law in arbitration agreements:

- If the parties have specified the law governing the main contract, this law applies to the arbitration agreement, rather than the law of the arbitration's seat (if different).

- If the contract is silent on the applicable law, the law of the arbitration's seat governs the agreement.

A grey area arises if no law governs the main contract, and the law of the seat differs from the law where the contract is performed. Rule 40.3 suggests the tribunal should consider relevant trade usages, but this is not binding, and the parties may argue for a different law (e.g., if the chosen seat was selected due to an unstable legal system where the contract was performed).

15. How is the law applicable to the substance determined? Is there a specific set of choice of law rules in your country?

The arbitral tribunal will resolve the dispute by either (a) applying the law selected by the parties that is relevant to the substance of the dispute or (b) if agreed upon by the parties, using any other considerations they specify or that the tribunal determines. When parties select a law, it pertains to the substantive laws of a jurisdiction rather than its conflict of law principles. In the absence of such an agreement, there are no mandatory choice of law rules that the tribunal must follow; instead, it will apply the law as dictated by the relevant conflict of laws rules (section 62 of the Act).

16. In your country, are there any restrictions in the appointment of arbitrators?

Section 22 of the Act reflects Article 11 of the Model Law concerning the appointment of arbitrators. It does not stipulate any specific conditions regarding the qualifications or characteristics of arbitrators. There are no nationality restrictions unless the parties agree otherwise. Additionally, the parties have the autonomy to determine both the number of arbitrators and the process for their selection.

17. Are there any default requirements as to the selection of a tribunal?

Section 22 of the Act default provisions for the appointment of arbitrators which apply in the absence of agreement between the parties, including time limits. If there is no agreement for three arbitrators, each party appoints one, and those two select a third; failing this within 30 days, the BVI IAC will appoint the third arbitrator (s. 22). For a sole arbitrator, the BVI IAC will make the appointment if the parties cannot agree (s. 22). Article 8 of the Rules establishes that if the number of arbitrators is not specified, the default is one unless the BVI IAC determines that three are more appropriate. Article 9 states the CEO of the BVI IAC will appoint a sole arbitrator if parties fail to agree within 30 days, while Article 10 outlines the role of the CEO in appointing arbitrators for a panel of three when multiple claimants or respondents cannot agree. Article 11 allows the CEO to constitute the arbitral panel upon request, ensuring timely resolution of arbitration proceedings.

18. Can the local courts intervene in the selection of arbitrators? If so, how?

Local courts can intervene in the selection of arbitrators under certain circumstances as outlined in section 22 of the Act. While the parties are generally free to agree on the procedure for appointing arbitrators, the Act provides mechanisms for court intervention if there is a failure to reach an agreement. Specifically, in an arbitration involving three arbitrators, each party appoints one, and those two appoint a third. If a party does not appoint their arbitrator within thirty days of a request, or if the two appointed arbitrators cannot agree on a third within thirty days, the court or designated authority may be called upon to make the appointment (s. 22(1)(a)). Similarly, for a sole arbitrator, if the parties are unable to agree, the court will appoint the arbitrator upon request (s. 22(1)(b)). Additionally, if there are issues with the appointment procedure agreed upon by the parties—such as a party's failure to act, a lack of agreement between the parties or arbitrators, or a third party's failure to fulfil their role—any party may request the court or designated authority to take necessary measures unless the agreed procedure provides alternative means for securing the appointment (s. 22(4)).

19. Can the appointment of an arbitrator be challenged? What are the grounds for such challenge? What is the procedure for such challenge?

The appointment of an arbitrator can be challenged under section 23 of the Act. Challenges can be made on specific grounds: (a) doubts regarding the arbitrator's impartiality or independence, and (b) doubts concerning the arbitrator's qualifications. Notably, if the challenging party is the one that appointed the arbitrator, the basis for the challenge must arise after the appointment to prevent misuse, such as challenging the arbitrator for adverse rulings on preliminary issues. Section 23 is further supported by articles 12 and 13 of the Rules, which emphasise the arbitrator's ongoing duty to disclose any circumstances affecting their impartiality and confirm their availability to dedicate adequate time to the arbitration. The procedure for challenging an arbitrator is detailed in section 24 of the Act and is supplemented by Article 14 of the Rules.

20. Have there been any recent developments concerning the duty of independence and impartiality of the arbitrators, including the duty of disclosure?

No recent developments. See question 30 below.

21. What happens in the case of a truncated tribunal? Is the tribunal able to continue with the proceedings?

In the event of a truncated tribunal, the proceedings can continue. If an arbitrator's mandate ends, a substitute arbitrator will be appointed following the same rules used for the original appointment (section 26 of the Act). The Rules further clarify this process: Article 15 grants the CEO of the BVI IAC the authority to modify the original appointment procedure if necessary, or, if the hearings are completed, to allow the remaining arbitrators to issue a decision or award. Article 16 stipulates that if an arbitrator is replaced, the hearings will resume from the point where the previous arbitrator left off, unless the other arbitrators decide, after consulting the parties, to rehear any or all issues. Additionally, if an equal number of arbitrators is appointed for any reason, Sections 28 and 29 of the Act provide the procedure for selecting an umpire, who may serve as a sole arbitrator to resolve specific issues.

22. Are arbitrators immune from liability?

Section 101 of the Arbitration Act stipulates that arbitrators cannot be held liable for any act or omission carried out in the course of their duties, except in cases where bad faith can be proven. Additionally, Article 17 of the Rules further reinforces this immunity by stating that parties waive any claims against arbitrators for acts or omissions related to the arbitration that do not involve intentional wrongdoing.

23. Is the principle of competence-competence recognised in your country?

Section 32 of the Arbitration Act enshrines the principle of competence-competence in BVI law. The arbitral tribunal may rule on its own jurisdiction, including any objections with respect to the existence or validity of the arbitration agreement or whether it has exceeded its authority during the course of the arbitration.

24. What is the approach of local courts towards a party commencing litigation in apparent breach of an arbitration agreement?

According to section 18 of the Act, the BVI Court will enforce arbitration agreements if a party requests a stay of proceedings to refer the matter to arbitration at or before the submission of their first substantive statement. The only exception to this mandatory stay occurs when the court deems the arbitration agreement to be null and void, inoperative, or incapable of being performed (see Question 13). Notably, even in such circumstances, the commencement or continuation of arbitral proceedings is permissible while the court considers the stay issue. The courts are also empowered to issue anti-suit injunctions where a party has commenced court proceedings in another jurisdiction (see Question 28).

25. What happens when a respondent fails to participate in the arbitration? Can the local courts compel participation?

The Arbitration Act and accompanying Rules provide robust measures to address a respondent's failure to participate in arbitration. Section 51 of the Act, which mirrors Article 25 of the UNCITRAL Model Law, establishes that if a respondent does not communicate their statement of defence, the arbitral tribunal may continue proceedings without considering the failure as an admission of the claimant's allegations (section 51(1)(b)). Furthermore, if a party fails to appear at a hearing or present evidence, the tribunal can proceed and make an award based on available evidence (section 51(1)(c)). If a party neglects to comply with the tribunal's orders without sufficient cause, the tribunal may issue a peremptory order, and subsequent non-compliance could lead to various consequences, including adverse inferences drawn against the non-compliant party (section 51(3)-(4)). Additionally, Section 53(2) empowers the court to compel participation by requiring a party to attend hearings or provide evidence, with similar powers conferred on the arbitral tribunal under section 54. If necessary, the tribunal can order interim measures to preserve assets and maintain the status quo (section 33), while the court retains the authority to intervene similarly under section 43. Furthermore, Article 1 of the Rules enables a party to seek an emergency arbitrator for urgent interim remedies, thereby safeguarding the integrity of the arbitration process against uncooperative respondents.

26. Can third parties voluntarily join arbitration proceedings? If all parties agree to the intervention, is the tribunal bound by this agreement? If all parties do not agree to the intervention, can the tribunal allow for it?

Third parties can join arbitration proceedings if the Arbitration Committee permits it based on a Request for Joinder (article 32).

If all parties, including the third party, agree to the joinder, the Arbitration Committee must grant the request (article 32.7), but the tribunal's final jurisdiction over the third party remains subject to its determination (article 32.11).

If all parties do not agree, the Committee can still allow the joinder, provided it is satisfied the third party may be bound by the arbitration agreement (article 32.8).

27. What interim measures are available? Will local courts issue interim measures pending the constitution of the tribunal?

Tribunals can grant interim measures, including asset preservation orders, injunctions, evidence preservation orders, and orders to maintain the status quo (section 33). Rule 27 mirrors this and allows the tribunal to require security for potential damages. The Rules also provide for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator for urgent relief before the tribunal is constituted (Appendix 1).

BVI courts can issue interim measures before or during arbitration, even if the tribunal hasn't been formed (sections 19 and 43). Court orders are not appealable, and parties can seek relief from the court without tribunal or party consent, though the court may defer to the tribunal if appropriate.

28. Are anti-suit and/or anti-arbitration injunctions available and enforceable in your country?

The BVI courts can issue anti-suit injunctions under section 24 of the West Indies Associated States Supreme Court (Virgin Islands) Act to protect arbitration agreements. In International Trading Holding Co Ltd & Anor v Med Trading Ltd (BVIHCMAP2020/0002), the court emphasised its role in enforcing arbitration clauses and preventing litigation in breach of such clauses, approving the approach in Enka Insaat Sanayi A.S. v OOO "Insurance Company Chubb" [2020] EWCA 574. The key considerations include whether foreign proceedings are vexatious, oppressive, interfere with the court's process, or are otherwise unconscionable (Emmerson International Corp v Viktor Vekselberg (BVIHCMAP2020/011)).

BVI courts also have jurisdiction to grant anti-arbitration injunctions. The guiding principle of non-intervention under the Arbitration Act does not override the court's inherent jurisdiction to issue injunctions under section 24 of the Supreme Court Act (Sonera Holding B.V. v Cukurova Holding AS (BVIHCMAP2015/0005)).

29. Are there particular rules governing evidentiary matters in arbitration? Will the local courts in your jurisdiction play any role in the obtaining of evidence? Can local courts compel witnesses to participate in arbitration proceedings?

Tribunals have broad discretion with respect to evidentiary matters. In the absence of parties establishing the evidentiary procedure, tribunals can conduct the arbitration as it deems fit, including determining the admissibility, relevance, and weight of evidence (sections 45 and 50). The Rules similarly allow tribunals to manage evidence, request documents, and determine how witness testimony is handled (articles 28(2), 28(3), and 28(4)), and subject to party agreement, determine the dispute solely on the papers (article 4(5)).

Tribunals or parties can request BVI court assistance to obtain evidence, including compelling witness testimony or document production (section 53).

BVI courts can compel witnesses, but only those within the court's jurisdiction. Non-compliance may lead to contempt of court proceedings.

30. What ethical codes and other professional standards, if any, apply to counsel and arbitrators conducting proceedings in your country?

The Rules do not specify ethical standards for counsel, but lawyers practicing in the BVI must follow the Legal Profession Act, which mandates integrity, competence, and avoiding conflicts of interest. The IBA Guidelines on Party Representation in International Arbitration are also often referred to in arbitration proceedings to provide clarity on ethical standards for counsel.

Arbitrators must be impartial and independent (article 12). They must disclose any potential conflicts throughout the proceedings and can be challenged if impartiality is questioned (article 13). The Rules also require the arbitrator to provide an affirmative statement that she is impartial, independent, available to devote the necessary time and conduct the arbitration diligently (Appendix C). International standards including the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration, UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, and CIArb Code of Conduct also guide arbitrators.

31. In your country, are there any rules with respect to the confidentiality of arbitration proceedings?

BVI law does not automatically impose confidentiality in arbitration, however confidentiality is an implied obligation unless the parties agree otherwise and with exceptions for public interest or legal requirements. Proceedings under the Act are to be heard in chambers (section 14) and all hearings related to arbitration are private unless ordered otherwise (section 16). The Act allows limited publication of judgments with party consent, with parties having the liberty to apply for redactions (section 15).

The Rules impose strict confidentiality on all parties, participants, and documents unless agreed otherwise or required by law (articles 18.6, 18.7, 39.9).

32. How are the costs of arbitration proceedings estimated and allocated? Can pre- and postaward interest be included on the principal claim and costs incurred?

Both pre- and post-award interest can be included on the principal claim and costs. Tribunals can award interest on any sum for the period up to the final award, unless the parties agree otherwise (section 77). Tribunals can also award interest from the date of the award until payment (section 78). The Rules also support awarding such interest, with the tribunal determining the rate, unless otherwise agreed (article 39.4).

33. What legal requirements are there in your country for the recognition and enforcement of an award? Is there a requirement that the award be reasoned, i.e. substantiated and motivated?

Convention awards can be enforced by either filing an Originating Application (ex parte) with the High Court, supported by the original or certified copy of the award and arbitration agreement, and certified translations if they are not in English (section 84). The court order must be served on the party against whom enforcement is sought before the award can be enforced.

For non-Convention awards, the enforcing party cannot commence an action in the BVI High Court and must apply for leave under section 82, filing the same documents required for Convention awards. An affidavit must support an enforcement application (CPR 43.10). The affidavit must exhibit the award, provide an address for service on the respondent, and certify the amount due. Once registered, the award is recognised as a court order.

The award must be reasoned unless the parties agree otherwise (section 65), or the award is based on settlement terms (section 64).

34. What is the estimated timeframe for the recognition and enforcement of an award? May a party bring a motion for the recognition and enforcement of an award on an ex parte basis?

The estimated timeframe varies based on factors such as court availability and case complexity. Generally, uncontested awards are quickly enforced, taking a few weeks to a few months. However, if the award is contested, the process may extend to several months due to court hearings and additional submissions.

Ex parte applications for recognition and enforcement are based on court practice rather than explicit statutory language and CPR Part 11, which governs ex parte applications.

35. Does the arbitration law of your country provide a different standard of review for recognition and enforcement of a foreign award compared with a domestic award?

The same standards of review apply to both domestic and foreign arbitration awards generally. However, there are distinctions between Convention awards and nonConvention awards. While procedural requirements are largely similar, the court can decline enforcement of a non-Convention award for any reason it deems just (section 83(2)), which is not a ground for refusing a Convention award. Additionally, enforcement of a nonConvention award requires leave of the court (section 81(1)), whereas a Convention award can be enforced either by leave or by instituting an action (section 84(1)). Furthermore, Convention awards are treated as binding for all purposes and can be relied upon in legal proceedings in the BVI (section 84(2)).

36. Does the law impose limits on the available remedies? Are some remedies not enforceable by the local courts?

There is no explicit limit on available remedies. A tribunal may award any remedy permitted by the arbitration agreement or any remedy that a court could order in civil proceedings, including specific performance unless otherwise agreed by the parties (section 68). These remedies are generally enforceable by local courts unless they violate BVI public policy or fall under statutory grounds for setting aside or refusing enforcement of an award.

37. Can arbitration awards be appealed or challenged in local courts? What are the grounds and procedure?

There is no general right of appeal on the merits of an arbitral award, but a party may appeal on a question of law following the procedures in Schedule 2, paragraph 5 of the Act. Awards can be challenged based on specific grounds outlined in the Act, including lack of jurisdiction, procedural unfairness, excess of authority, irregular tribunal composition, public policy violations, nonarbitrability, or if the award has already been set aside by the courts at the seat of arbitration (section 83).

For Convention awards, enforcement cannot be refused except on specified grounds (section 86), and the court cannot refuse enforcement for any other reason. If a party believes the tribunal lacks jurisdiction, they may raise this issue with the tribunal (section 32 of the Act and article 24 of the rules).

To challenge an award, an application for setting aside must be made within three months of receiving the award (section 79). The applicant must provide evidence supporting their challenge based on the grounds listed above.

38. Can the parties waive any rights of appeal or challenge to an award by agreement before the dispute arises (such as in the arbitration clause)?

Parties can agree to waive or limit certain rights of appeal, including appeals on points of law and serious irregularities (sections 91 and Schedule 2, paragraphs 3 and 4 of the Act) and some procedural objections (section 9). However, they cannot waive their rights to appeal or challenge an award before a dispute arises, as the legislation aims to preserve basic procedural rights until the specific circumstances of a dispute are clear.

39. In what instances can third parties or nonsignatories be bound by an award? To what extent might a third party challenge the recognition of an award?

Third parties or non-signatories can be bound by an arbitration award as awards are final and binding on both parties and any person claiming through them (section 71(1)). Third parties may be bound by an award in cases of assignment of contractual rights, novation of parties, or consent to join the arbitration (article 32 of the Rules).

While third parties typically have limited standing to challenge recognition of an award, they may do so if they believe they are improperly bound, or their rights are affected. Grounds for challenge include lack of jurisdiction over the third party, improper joinder, or that the award resulted from fraud or illegality.

40. Have there been any recent court decisions in your jurisdiction considering third party funding in connection with arbitration proceedings?

Recent decisions in the BVI have acknowledged the evolving landscape of third-party funding in arbitration and litigation. Crumpler v Exential Investments Inc (BVIHC(COM)2020/0081) marked the first endorsement of third-party funding for legal and liquidator costs

Leremeieva v Estera Corporate Services (BVIHCOM2017/0118) confirmed that third-party funding is allowed as long as it does not give excessive control to funders or lead to unreasonable returns. However, the boundaries of these doctrines remain unclear due to limited case law and legislative intervention.

41. Is emergency arbitrator relief available in your country? Are decisions made by emergency arbitrators readily enforceable?

Appendix 1 of the Rules governs emergency arbitrator relief. While decisions made by emergency arbitrators are generally binding, their enforceability may face judicial scrutiny based on the validity of the arbitration agreement and due process principles. Additionally, the arbitral tribunal has the authority to revoke, modify, or terminate the emergency arbitrator's decisions, including those regarding costs.

42. Are there arbitral laws or arbitration institutional rules in your country providing for simplified or expedited procedures for claims under a certain value? Are they often used?

The Rules allow for an expedited procedure for claims up to USD 4,000,000, applicable if the parties agree or if a party requests it before the tribunal is constituted, and the Arbitration Committee finds the case exceptionally urgent (Article 2, Appendix 2). However, the expedited procedure is not available for agreements made before its implementation on November 16, 2021, if parties opt out, or if the Arbitration Committee determines it's inappropriate (Article 3, Appendix 2). Its usage frequency is not specified.

43. Is diversity in the choice of arbitrators and counsel (e.g. gender, age, origin) actively promoted in your country? If so, how?

The BVI actively promotes diversity among arbitrators and counsel – section 22(1) of the Act allows individuals of any nationality to serve as arbitrators unless agreed otherwise. The BVI IAC emphasises diversity in its roster of arbitrators from over 40 countries, encouraging appointments based on gender, origin, experience, and age.

44. Have there been any recent court decisions in your country considering the setting aside of an award that has been enforced in another jurisdiction or vice versa?

In January 2023, in AB Limited et al v GH Limited (BVIHCOM2021/0192), the Commercial Court addressed the setting aside of an order enforcing arbitration awards from Singapore. The case focused on public policy, particularly the enforcement of compound interest deemed illegal under Thai law, which governed the underlying contract. While recognising the proenforcement approach typical under the New York Convention, the court ruled that it would not enforce an award that contravened public policy, citing concerns about comity, illegality, and the integrity of judicial processes. Consequently, the BVI court refused to enforce the compound interest portion of the award.

45. Have there been any recent court decisions in your country considering the issue of corruption? What standard do local courts apply for proving of corruption? Which party bears the burden of proving corruption?

Recent BVI court decisions have not specifically addressed corruption in arbitration contexts, but broader corruption issues within public institutions have emerged after the 2022 BVI Commission of Inquiry. There are ongoing reforms aiming to enhance governance and transparency, which may indirectly affect arbitration.

In legal proceedings concerning corruption, the burden of proof lies with the party alleging corruption. BVI courts apply the civil standard of proof—balance of probabilities.

46. What measures, if any, have arbitral institutions in your country taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The BVI IAC adopted measures to ensure arbitration continuity while prioritising health and safety. Key actions included implementing virtual hearings and CMCs, allowing proceedings to continue via secure online platforms, as provided for in the Rules (article 29(1)). Additionally, the IAC enhanced electronic filing and document sharing systems, enables efficient handling of submissions and minimises physical contact.

47. Have arbitral institutions in your country implemented reforms towards greater use of technology and a more cost-effective conduct of arbitrations? Have there been any recent developments regarding virtual hearings?

Virtual hearings at the BVI IAC are standard, with tribunals empowered to conduct them remotely (article 19 of the Rules). The Centre's case management platform facilitates electronic filings and real-time communication, thereby streamlining processes and reducing costs. The Centre offers support for virtual hearings and development protocols to ensure security and comfort during video conferences. Furthermore, as an institutional supporter of the Campaign for Greener Arbitrations, the IAC promotes environmentally sustainable practices in arbitration, reflecting its commitment to modernising the arbitration process while prioritising sustainability.

48. Have there been any recent developments in your jurisdiction with regard to disputes on climate change and/or human rights?

While specific disputes on climate change and human rights are not widely reported in the BVI, the Territory recognises the importance of these topical issues. The BVI Climate Change Programme, overseen by the Ministry of Environment, aims to address challenges through public education and adaptation strategies. The BVI Government recently sought public feedback on the Human Rights Commission Bill, 2024, which aims to establish a commission to investigate human rights complaints and promote public awareness of human rights issues.

49. Do the courts in your jurisdiction consider international economic sanctions as part of their international public policy? Have there been any recent decisions in your country considering the impact of sanctions on international arbitration proceedings?

BVI courts have not explicitly ruled on international economic sanctions as part of their public policy regarding arbitration. However, in JSC VTB Bank v Sergey Taruta (BVIHCOM2014/0062), the court addressed sanctions in the context of legal representation, emphasising that lawyers could not abandon a sanctioned client without court permission. Additionally, sanctions may impact the enforcement of arbitral awards under the Convention, where courts can refuse enforcement if it violates public policy, potentially including international sanctions from bodies including the UN or EU.

50. Has your country implemented any rules or regulations regarding the use of artificial intelligence, generative artificial intelligence or large language models in the context of international arbitration?

The BVI has not implemented any such rules or regulations.

Originally published by Legal500.

Footnote

1. https://bviiac.org/cooperation-agreements/

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.