- within Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit industries

Vietnam's investment landscape

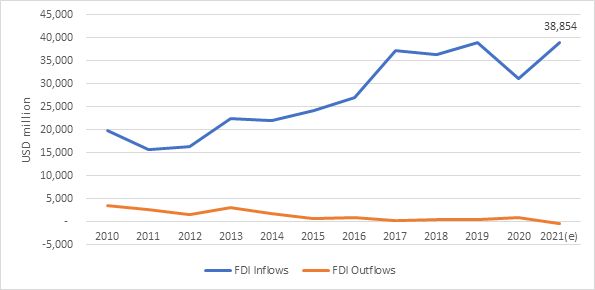

Vietnam has consistently been an attractive destination for foreign investment. Following the financial crisis of 2008-9, FDI inflows regained growth momentum at an average rate of 6.3% annually from 2010 to 2021. Among the top FDI investors in Vietnam are the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, and The Netherland. Key sectors attracting FDI inflow are manufacturing, real estate, and energy. Specifically, manufacturing accounted for around 58% of FDI inflow in 2021, confirming the position of Vietnam as an emerging manufacturing base. FDI outflows, on the other hand, have declined since 2008. Vietnam's outbound investment is concentrated primarily in the neighbouring region of Lao PDR and Cambodia.

Figure 1 FDI Inflows into and Outlfow from Vietnam, 2010-2021

Source: GSO

Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS)

Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) is a popular investor protection mechanism under the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) which proliferated in the Asia-Pacific in the 1990s and 2000s. Backlash against ISDS however arose due to the claims brought against the countries that allegedly might have caused 'regulatory chill', especially in areas affecting people welfare and environmental protection.1

| Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) is a mechanism, typically contained in a free trade agreement (FTA) or investment treaty, that provides foreign investors with the right to access an international tribunal against the government in the country where the investors have invested to resolve investment disputes. |

Frictions between the investors and government on specific aspect of carrying out investment projects is unavoidable, thus the need for mechanisms for investors to redress their concerns. These might include domestic courts, administrative tribunals, or arbitration tribunals which are provided for under the several bilateral investment treaties (BIT) or Investment chapter of free trade agreements (FTA). According to data by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), there are 1,229 known treaty based ISDS cases as of 2022, 852 of which have been concluded.

Vietnam has signed 67 BITs, 50 of which are currently in force. Additionally, Vietnam also signed 27 regional trade agreements, framework agreements or other agreements with investment provisions. Many of these contains a mechanism for resolving dispute between investor and States following the traditional ISDS approach, which will be explored below under the CPTPP framework. Since 2004, Vietnam has recorded nine known ISDS cases, including three pending cases with investors from the United Kingdom, the Republic of Korea, and the United States.

Figure 2 Countries with which Vietnam has an FTA and which contain an ISDS chapter, as of February 2023

Note: ISDS provisions and process differ by FTA. Coloured countries

are those with an FTA containing an ISDS provision with Vietnam.

Source: Authors

ISDS under the CPTPP

ISDS is provided under Section 9B of Chapter 9 of the CPTPP, featuring a two-tiered dispute resolution mechanism. The rules however enable investors to commence arbitration without any prior recourse to domestic proceedings or remedies.

Investors are entitled to bring a claim based on the breaches of obligations regarding a "covered investment" under Section 9A of the Agreement. Where the respondent Party is Chile, Mexico, Peru, or Vietnam, the CPTPP precludes investors from bringing arbitration claims which have already been pursued before domestic courts or administrative tribunals (so called fork-in the-road clause) (Annex 9-J). Where disputes arise concerning similar rights or obligations under multiple trade agreements, the investor may select the forum in which to settle the dispute. Once the complainant requested the establishment of the tribunal under one agreement, the forum selected shall be used to the exclusion of other fora (Article 28.4).

The CPTPP excludes natural person (i.e., individual) investor to submit a claim to arbitration against a Party to which that natural person investor holds nationality.2 For example, a Vietnamese who is also a permanent resident of Canada may not submit a claim to arbitration against Vietnam. For juridical person (i.e., organisation) investor, the claimant may submit a claim for arbitration on its own behalf or on behalf of an enterprise that the claimant owns or controls directly or indirectly.

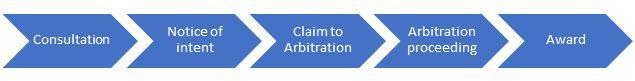

Before commencing arbitration, the claimant is required to deliver "a written request for consultations setting out a brief description of facts regarding the measure or measures at issue" (Article 9.18.2). If the dispute is not resolved within six months of the receipt by the respondent of such written request for consultations, the claimant may submit to arbitration a claim that that the respondent has breached an obligation under the Agreement's investment chapter, and any loss or damage that has incurred by reason of, or arising out of, that breach.

The claimant is also required to deliver to the respondent a written notice of intent to submit a claim to arbitration containing specified details on the claim 90 days before submitting such claim to arbitration (Article 9.19.3). The said written notice must also be accompanied by a written waiver "of any right to initiate or continue before any court or administrative tribunal under the law of a Party, or any other dispute settlement procedures, any proceeding with respect to any measure alleged to constitute a breach referred to in Article 9.19" (Article 9.21.2(b)).

The CPTPP provides a time limitation to initiate an investment arbitration. This period is three years and six months, counting from the date the investor first acquired, or should have first acquired, knowledge of the breach (Article 9.21.1). Arbitration may be initiated in accordance with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) Convention and the ICSID Rules of Procedure for Arbitration Proceedings; the ICSID Additional Facility Rules; the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules; or any other arbitral institution or arbitration rules that the claimant and respondent agree on (Article 9.19.4).

Unless the disputing parties agree otherwise, the arbitral tribunal shall comprise three arbitrators, with one arbitrator appointed by each of the disputing parties and the presiding arbitrator appointed by agreement of the disputing parties. If a tribunal has not been established within 75 days of the submission of the arbitration claim, the Secretary-General of ICSID shall appoint the arbitrators not yet appointed at the request of a disputing party.

Arbitral tribunals constituted via the ISDS mechanism in the CPTPP may only award (separately or in combination): (a) monetary damages and interest thereon; and (b) restitution of property (in which case the award shall provide that the respondent may pay monetary damages and any applicable interest in lieu of restitution).

Carve-outs

The CPTPP contains a number of carve-outs that limit the application of the ISDS under the Agreement. Compared to the text of the TPP-12 (which the US pulled out from), the CPTPP suspends the references to, and thus application of ISDS to, claims arising out of investment authorisations and investment agreements.3

Vietnam signed a side letter with New Zealand to exclude the direct application of ISDS provisions. Accordingly, any dispute between an investor and the respondent State that would otherwise be subject to ISDS under the Investment Chapter must comply with a procedure similar to the first tier of the dispute resolution (i.e., consultation and negotiations) for six months. For the second tier (commencement of arbitration) to operate, the respondent State must provide specific consent to the application of arbitration under the Investment Chapter to the dispute.

Furthermore, the CPTPP includes a 'tobacco carve-out' that preserves the States' public policy space in adopting tobacco control measures. Article 29.5 (Tobacco Control Measures) of Chapter 29 (Exceptions and General Provisions) states that a Party may elect to deny the benefits of Section B of Chapter 9 (i.e., the application of the ISDS mechanism) concerning claims challenging a tobacco control measure of that Party. The denial of benefit can be made at the time of the submission of such a claim to arbitration or during the proceedings.

Other approaches to the ISDS mechanism

The ISDS mechanism has been subject to criticism. Opponents raised several concerns over the ISDS system, including the unpredictability; the lack of transparency of arbitral proceedings; the lack of independence and impartiality of arbitrators; and the lack of right of appeal.4 Hence, it is inevitable that many governments have tried to address these handicaps.

For example, the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA) allows for the tribunal to request the Member States to provide a joint interpretation of any provisions of the ACIA. The Member States will then have 60 days of the delivery of the request to submit the joint interpretation, failing which the tribunal would be entitled to decide the issue on its own account.

In an effort to reform the existing ISDS mechanism, the EU supports the creation of a multilateral investment court for disputes arising from bilateral EU investment agreements. This mechanism is featured in, for example, the European Union-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CEPA), the European Union–Singapore Investment Protection Agreement (EUSIPA) and the European Union–Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement (EUVIPA). It comprises of both a permanent investment tribunal and a permanent appeal tribunal. In the case of the EUVIPA, the permanent investment tribunal comprises nine members, with three from the European Union, three from Vietnam, and three from third countries. The Members of the Tribunal will be appointed for a four-year term, renewable once. Among these nine tribunal members appointed immediately after the entry into force of the Agreement, five tribunal members, to be determined by lot, shall have their terms extend to six years. This mechanism is supposed to ensure the continuity of the tribunal. The Tribunal will hear cases in divisions consisting of three Members, one from each of the above three cohorts, and will be chaired by the Member from a third country.

The Appeal Tribunal shall be composed of six Members, two from the European Union, two from Viet Nam, and two from third countries. Similar to the Tribunal Members, the Appeal Tribunal Members shall be appointed for a four-year term, renewable once. Among these appointed immediately after the entry into force of the Agreement, three will have an extended term of six years. The permanent appeal tribunal would hear appeals from the awards issued by the permanent investment tribunal.

The RCEP, another mega-deal that Vietnam is a member of, does not currently contain ISDS provisions in its investment chapter. The ISDS mechanism was said to have been carved out during the negotiations to avoid delays in its conclusion. Furthermore, the RCEP also explicitly prohibits applying its MFN clause to access the ISDS mechanisms or procedures contained in other agreements (Article 10.4(3)). Instead, the RCEP Member States agreed to start negotiations on ISDS provisions within two years of the RCEP coming into force, and for these negotiations to be concluded within three years (Article 10.18). RCEP entered into force on 1 January 2022 when ten countries first ratified the Agreement,5 therefore the deadline for ISDS provision negotiations is approaching. It would be interesting to see which approach the RCEP members would choose to adopt for its ISDS system.

What should businesses be mindful of?

The ISDS mechanism in investment treaties has traditionally been considered a means of attracting inbound FDI. But as Vietnam's outbound FDI increases, this mechanism can also be used as a means of protecting the overseas investments of Vietnamese investors. Rather than completely abandoning ISDS, states are working on different approaches to reform the system. While the ISDS system under the CPTPP has taken effect, the new system under the EUVIPA is still pending ratification of the agreement. For the RCEP, which lacks an ISDS mechanism, investment-related dispute can be solved either under the state-to-state dispute settlement mechanisms or under another FTA with ISDS provision between Vietnam and the investment hosting country, for example the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand free trade agreement (AANZFTA). Therefore, Vietnamese investors should be mindful of the measures available for them to protect their legitimate interest in different host countries where their investment interests are.

Footnotes

1. Kyla Tienhaara (2017). Regulatory Chill in a Warming World: The Threat to Climate Policy Posed by Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Transnational Environmental Law, Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2018, pp. 229-250. Cambridge University Press.

2. CPTPP, Article 9.1 (Definition), paragraph 2.

3. The TPP-11 define investment agreement as "written agreement that is concluded and takes effect after the date of entry into force of this Agreement between an authority at the central level of government of a Party and a covered investment or an investor of another Party and that creates an exchange of rights and obligations, binding on both parties under the law applicable [...]".

4. Alvarez et al. (2016) 'A Response to the Criticism against ISDS by EFILA', Journal of International Arbitration, Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2016, Volume 33 Issue 1) pp. 1-3

5. These are: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Japan, Laos, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. RCEP entered into force for the Republic of Korea on 1 February 2022, for Malaysia on 18 March 2022, and for Indonesia on 2 January 2023. The Philippines ratified the deal on 21 February 2023. The RCEP will therefore enter into force for the Philippines 60 days after the deposition of its instrument of ratification with the Depositary.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.