When corporate buyers are looking at acquiring another company, the executive team often wonders what rate of return they should be seeking on their invested capital. Using a low rate of return could cause the buyer to overpay, and not provide adequate compensation for the risk that the acquired company’s financial results will fall short of expectations following the transaction. A high rate of return could mean that the buyer’s offer isn’t competitive, and the seller chooses another suitor.

Rates of return are highly subjective, and there is no “right” answer per se. However, buyers should consider the following factors when developing rates of return for the purpose of corporate acquisitions: (i) prevailing risk-free rates; (ii) an equity risk premium; (iii) liquidity risk; (iv) company-specific risk; and (v) debt capacity.

PREVAILING RISK-FREE RATES

Appropriate rates of return are a function of alternative investments that can be made with available capital. Since corporate acquisitions represent long-term investment decisions, the starting point in the rate of return analysis should be the yield on long-term Government bonds, which represents a “risk-free” investment alternative. As of May 2014, the yield on long-term Government of Canada bonds is approximately 3%.

EQUITY RISK PREMIUM

Since corporate acquisitions represent equity investments, the next element to consider is the premium that a buyer could expect to generate by investing in the stock market in general, as opposed to risk-free government bonds. While equity returns fluctuate each year, over the long-term the equity risk premium (which reflects capital appreciation and dividend income for stocks listed on major indices such as the TSX or S&P 500) has been about 5%.

LIQUIDITY RISK

Adding the yield to maturity on long-term government bonds (3%) and the equity risk premium (5%) suggests that an equity investment should generate a return of about 8% per annum, over the long-term. But it’s important to recognize that this represents the return on a very liquid and highly diversified stock portfolio such as the TSX or S&P 500. Both of these elements are missing when a buyer acquires a private company. Therefore, the rate of return has to be adjusted accordingly.

With respect to liquidity, an investor could sell most publicly traded shares in minutes if they no longer wanted to be invested. However, the divestiture of a private company normally takes between six to 12 months to complete, during which time the owners are exposed to the risk of adverse developments which could erode the company’s value. Furthermore, unlike publicly traded stocks where the price is readily known, there’s uncertainty regarding the price that might be obtained for a private company when it’s sold in the open market.

Liquidity risk is difficult to quantify, but a benchmark that’s sometimes used is based on the observed discounts in restricted stock studies. That is, shares of public companies that are not freely tradable for a period of about six months to 24 months are worth less than comparable shares that can be readily liquidated. There have been numerous studies conducted on this topic and the results differ in each case. However, the median discount for restricted stock has been around 20% (i.e. restricted shares are worth about 20% less than comparable shares without restrictions). Converting this discount into rates of return for private company acquisitions suggests that target rates of return should be increased by about 2% to compensate for liquidity risk.

COMPANY-SPECIFIC RISK

As previously discussed, the equity risk premium is based on a stock portfolio that enjoys the benefits of liquidity and diversification. Liquidity risk was addressed above. In the absence of diversification, buyers need to consider company-specific risk inherent in the acquisition target. This can be highly subjective. As a very general guideline, company-specific risk can range from about 2% for larger, well-established companies with a strong competitive advantage, to 10% (or more) for smaller companies that are dependent on a handful of customers or certain employees (e.g. the business owner). While not an exhaustive list, some of the factors that buyers should consider when quantifying company-specific risk for an acquisition target include:

- whether its product and service offerings have a differential advantage or, alternatively, whether the company must compete primarily on the basis of price;

- the degree of customer concentration and repeat business;

- the breadth, depth and commitment of the management team;

- whether historical operating results have been relatively stable or volatile; and

- industry-specific risk factors such as the competitive landscape, regulations, and major trends.

Combining the risk-free rate with the equity risk premium, liquidity risk premium and company-specific risk premium suggests that a return on equity for a corporate acquisition should be in the range of about 12% to 20%, with the major variable being company-specific risk. Note that this assumes the acquisition target is an established company, as opposed to an early-stage business or venture capital type investment, for which rates of return can be significantly higher.

DEBT CAPACITY

A buyer’s ability to use debt in lieu of equity in order to finance an acquisition helps to reduce the required rate of return. This is because the interest rate on debt financing is lower than the required return on equity financing, particularly given that interest expense is tax-deductible.

Whether or not a buyer intends to use debt as a source of financing, rates of return for corporate acquisitions should be based on the target company’s ability to accommodate senior debt in its capital structure. Debt financing ratios are subjective but they are mainly driven by lenders looking for the following two factors:

- the level and stability of cash flows, which are required to service interest and principal repayments; and

- the quantum and nature of assets that can be used as security.

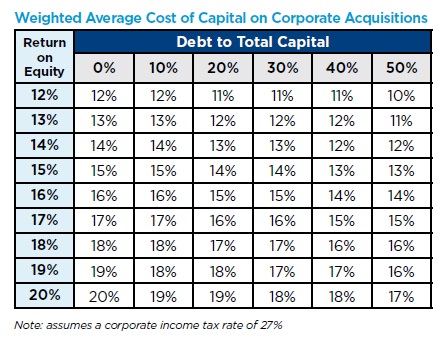

It’s important to note that while debt is attractive due to its low cost, the use of debt introduces financial risk, which increases the required return on equity. This is because debt financing ranks ahead of equity financing in its claim against the cash flows and assets of the acquired company. While there are formulas for calculating the impact of debt financing and financial risk, the following table can be used to provide an indication of the resultant “weighted average cost of capital,” i.e. the required rate of return for an acquisition target, given the estimated return on equity and debt utilization.

These represent after-tax rates of return on total capital. Therefore, they should be applied to forecast discretionary cash flow for the target company, calculated as cash flow after capital expenditure requirements and corporate income taxes, but before debt servicing costs.

SUMMARY

In the end, rates of return are subjective. Therefore, buyers should prepare economic models that allow for sensitivity analysis. Rates of return may also be adjusted where an acquisition target is considered highly strategic. In addition, buyers (and sellers) should remember that the terms of the deal (i.e. how and when the purchase price is paid) are just as important as the purchase price itself. However, buyers can make a more informed decision about the rate of return to apply when assessing corporate acquisition opportunities by considering the various components that comprise rates of return. Remember, they include: (i) prevailing risk-free rates; (ii) the equity risk premium; (iii) liquidity risk; (iv) company-specific risk and (v) debt capacity.