State aid and public procurement are legal subjects deriving from the law of the European Union ("EU"). Both regimes have a significant impact on large development projects. Projects containing elements of State aid and/or public procurement can, however, be managed in such a way as to avoid problems arising as a result. Careful consideration of the relevant issues, especially during a project's early stages, helps identify any potential difficulties and, in turn, prevent any such unwelcome results further down the line.

The risks are clear-cut:

- If State aid is not granted legally, it may lead to investigation and condemnation by the European Commission. This in turn can lead to a project being terminated or a public body being required to reco

- If public procurement rules are not appropriately observed, decisions taken by a contracting authority may be set aside or the contracting authority may face claims for damages from any aggrieved potential contractors who, as a result of the rules being breached, have lost the opportunity of winning the contract.

It is the obvious interests of all parties involved in regeneration projects to avoid either of the above.

State Aid

Identifying a State aid

State aid is the technical term for a subsidy granted by a national government or any extension thereof. To qualify as State aid, the following four elements must be present in a funding plan or package:

- A form of financial benefit received (i.e. revenue granted). Financial benefits may take several forms, such as: direct grants to establish a new production facility; writing-off debt; special tax concession or preferential loans or guarantees which are unavailable from private banks. It might even be the national administration of EU structural funds. In a development project, the benefit might typically be the sale, lease or purchase of land by public bodies to or from private parties at non-market prices or building infrastructure, which will only benefit private business and not the public. In all such cases private enterprises gain financial benefits they would not otherwise receive.

- Granted from "state resources". The financial benefit identified must come from the state or an extension of the state. Local authorities and councils and regional development authorities all qualify as extensions of the state in this sense and as such are regulated. For example, for local authorities, State aid often arises when grants are offered to attract overseas investment into particular regions.

- Granted to a specific beneficiary. Thirdly, the provision of benefits must involve selective financial assistance to particular firms or sectors. Grants or tax breaks which benefit all companies in a given region or industry will not qualify.

- Must cause an actual or potential distortion of competition, which may affect trade between Member States. Local authorities often fail to have sufficient regard to the effect of aid outside their localities and on trade generally. The European Commission and the European Courts, however, have always taken the restrictive view that, unless very special circumstances exist, one should assume the aid causes an actual or potential distortion of competition which may affect trade between Member States.

Managing State aid – when is it compatible?

If, by applying the above, a project is found to contain State aid, the project must be managed. Either the project must be restructured to eliminate those elements of aid, or the aid must be made lawful. State aid can only become lawful if authorised by the European Commission, through either of the two following routes:

- The aid package may be notified to the European Commission for individual approval; or

- It may receive deemed approval without notification on the basis that it fits within an already notified and approved general aid scheme, or a so-called "block exemption" Regulation (in which the Commission has outlined the conditions under which a State aid can be granted lawfully).

Whether or not aid ever becomes capable of being approved depends on its compatibility with the Common Market. This is determined by reference to a number of different criteria, which depend on the level or "intensity" of the aid (i.e., how much public aid is granted vis-à-vis private funding), its purpose, the beneficiary and the beneficiary's sector and the region in which the beneficiary is situated. A detailed framework of rules and guidelines exist to help with this process, which is particularly useful when dealing with sensitive sectors such as steel, textiles, automotive, air transport and shipbuilding, and for certain particular types of aid, for example for research and development.

Aid to disadvantaged regions receives preferential treatment provided it does not exceed certain intensity level thresholds, as reflected by "objective areas" defined on the basis of GDP per capita and by which the official EU map is divided. Whilst most of the UK is not eligible for "regional aid", certain areas do qualify at differing levels.

In effect, the process of granting state aid can be relatively straightforward if given careful consideration at a stage sufficiently early. The aim is to allow for measures to be put in place in order to ensure compatibility with the Common Market.

Public Procurement

Similarly to State aid, EU public procurement obligations usually arise in instances where public money is being spent. By the same tone, if disregarded or misinterpreted, the effects on any given project can be very severe.

What are the public procurement rules?

Public procurement rules are so-called "single market" measures emanating from the EU. They take the form of two EU Directives, which have been implemented in national law. The Directives require that contracts for works, supplies and services over a certain value let by the public sector (and "utilities" operating in the water, energy, transport and postal sectors), be advertised on an EU-wide basis. The purpose of this is to allow potential contractors from all 27 EU Member States opportunity to bid for the contract following a fair and equitable contest, which achieves the best value for money.

Three general features may be identified:

- The OJEU (Official Journal of EU) notice. This sets out in standard format the subject of the contract, the contracting authority, the award procedures etc.;

- The banning of discriminatory technical standards which prejudice against non-local suppliers; and

- Contracts may only be awarded following objective and transparent criteria for selection.

Why worry?

Breaching the public procurement regime may go unnoticed or unpunished. However, there is a risk assessment to be made and companies who ignore the rules are running the risk of being fined, award damages, or having to set aside decisions taken unlawfully. In Harmon vs. House of Commons for example, damages of over £5m were awarded to a contractor denied the opportunity to win a contract for lack of observance of the rules.

Breach of the rules bears real risk. Furthermore, many public authorities have their own internal procurement rules, which apply irrespective of EU obligations, and need to be followed. These are mainly concerned with achieving best value for money.

In addition to the possibilities of injunction at national court level, plus awards for damages and the award decisions being set-aside, further procedures exist for aggrieved contractors to complain to the European Commission. If satisfied that a breach has occurred, the Commission may complain to the Member State concerned, which may result in litigation before the European Court of Justice. In December 2007 a new Remedies Directive seeking to improve the right of rejected bidders was published. The Directive is designed to allow disappointed bidders enough time to initiate a review procedure before the contract is concluded and it seeks to combat illegal direct awards of public contracts, by rendering such contracts ineffective under certain circumstances. Member States have 24 months to transpose the Directive into national law.

Who is caught by the rules, and when?

The public procurement rules only apply when the following three conditions are met:

- The contract is awarded by a "contracting authority". The State, regional or local authorities, bodies governed by public law, or associations of such authorities are "contracting authorities". In Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs), often a private entity procuring contracts on behalf of a public body and using public money will also be caught. If private entities procure contracts for themselves using funds, the majority of which are supplied by a public authority, they too will be caught. The other group of contracting entities is the utilities – which includes all bodies defined as a "contracting authority" including wholly private undertakings operating under special or exclusive rights in the water, energy, transport or postal sector.

- The contract is in writing, for monetary value and for services, supplies or works. If nothing is being purchased, the rules do not apply. The purchase must be of works, services or supplies, so purchases of land are not caught. The contracts must be for monetary value, but this need not mean direct cash – it could be a return by way of investment, or a discount from a land purchase, for example.

- Various financial thresholds are exceeded. The Directives set out a number of thresholds, which are updated periodically. Below these thresholds relating to contracts for works, services and supplies, the rules do not apply, but public contracting authorities should still provide some form of competition for contracts where possible. The thresholds are complex depending on the nature of the contract and whether the utilities sector applies. In terms of the public sector, the "rule of thumb" thresholds are currently €206,000/£139,893 for services and supplies contracts (€133,000/£90,319 for contracts let by certain listed central government bodies) and €5,150,000/£3,497,313 for works contracts. For the utilities sector, the thresholds are €412,000/£279,785 for services and supplies contracts and again €5,150,000/£3.497,313 for works contracts (figures applicable as from 1 January 2008). Note however that contracts may not be artificially split to avoid the thresholds. If one job really is one job, then it is one contract and may not be split to avoid the rules. It should be noted that the EC Treaty applies to all contracts, and therefore, even where the above thresholds are not exceeded, contracting authorities must always adhere to the key Treaty principles of transparency and non-discrimination. The Commission proposes that authorities conduct a self-assessment of their schemes in order to decide on the degree of advertisement required for each specific contract.

Concluding remarks

Public procurement issues may arise whenever a public authority procures any works, services or supplies in the context of a development project either on its own behalf or in tandem with the private sector. This could be the appointment of a developer, a project designer or manager, or a remediation contractor. Likewise, the same needs could arise if the body doing the appointing is a PPP.

As with State aid, however, just because a contract award process is covered by the public procurement rules this need not be a problem. The contract award process does take time, but need not take more time than would be spent anyway, provided a project is carefully planned. Furthermore, the small costs incurred in observing the OJEU process may be more than recovered by savings achieved as a result.

Suffice to say, there are many possibilities when drawing up plans for regeneration projects and if public procurement issues arise they may sometimes be avoided by restructuring the deal or may be factored in so that they create no problems. The alternative horror story is that if ignored, an aggrieved contractor could at a later stage make life very difficult. This can and does happen but may be easily avoided if proper thought is applied in the early stages.

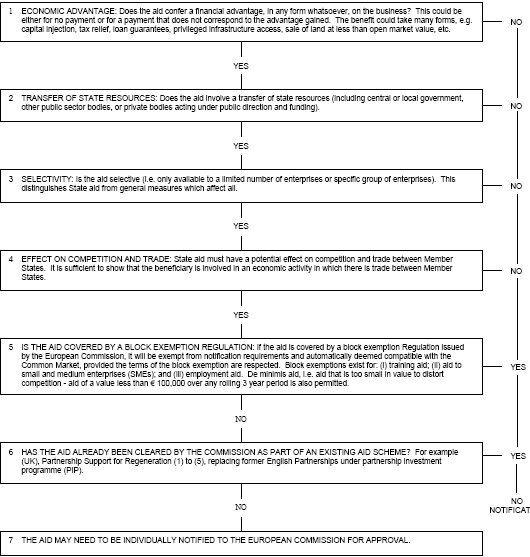

How to spot a state aid

Identifying State aid is not always straightforward. Companies receiving aid without prior approval risk having to repay it with interest. The brief flow chart below addresses the questions, which must be asked, when first assessing a potential State aid scenario. It is not a substitute for legal advice, which must be applied subjectively to each individual circumstance.

Other points to remember:

- Where a block exemption applies, the aid must comply with every condition.

- Even though aid requires individual notification, it may have every chance of obtaining the Commission's approval.

- Where notification applies, relevant Government offices must complete the notification (forms prescribed at Member State level).

- Special rules apply in "sensitive sectors", for which extra guidelines exist, notably: motor vehicles, steel, coal, agriculture, fisheries, synthetic fibres, shipbuilding, and transport.

- In all cases public funding, including any European structural funds allocation, must not exceed the relevant aid ceiling for a given geographical area.

- Very large awards for initial investment must still be notified even if the national aid scheme concerned has already been notified in general terms and approved.

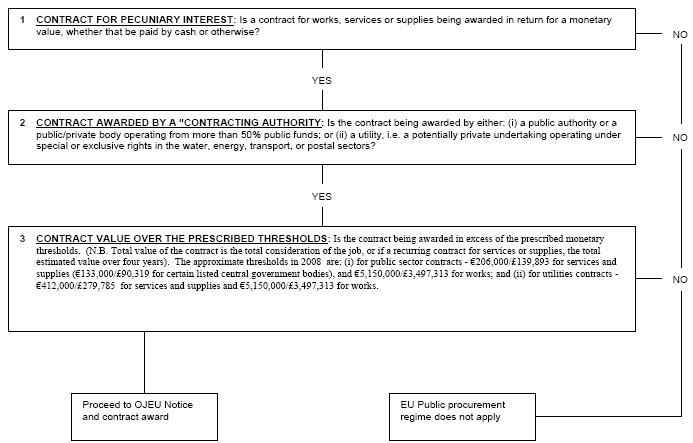

How to spot a contract subject to public procurement

"Public procurement" is the purchase of works, goods and services by public bodies. Public authorities and utilities in the energy, water, transport and postal sectors are required to advertise contracts over certain monetary thresholds in the Official Journal of the European Union ("OJEU") and to follow specific award procedures. The purpose of the EU procurement rules is to open up national procurement markets to cross-border competition.

Set out below is a brief chart identifying the situations in which contracts awarded are likely to be caught by the EU public procurement rules for competitive tendering by OJEU Notice. This is not in any way a substitute for legal advice, which must be applied subjectively to each individual circumstance.

Other points to remember:

- Contracts should not be artificially divided to avoid the thresholds.

- Contracts for the sale and purchase of land are not subject to the public procurement regime.

- Contracts awarded in breach of the rules may be set aside, lead to awards of damages in national courts and/or investigation by the European Commission.

- Contracts do not require OJEU tendering if they are performed by the Awarding Authority itself.

- Just because a contract awarded by a public authority is not subject to the EU public procurement regime, it will still be likely to be subject to governmental rules on best practice and value for money.

- The EU public procurement regime derives from EU Directives, but is specifically implemented in national law in all of the 27 EU Member States.

- Compliance with the EU procurement rules involves the following procedural steps: (i) sending a notice in the appropriate form for publication in the OJEU; (ii) conducting pre-selection of contractors to be invited to submit tenders or to negotiate; (iii) evaluating the tenders on the basis of the "lowest price" or the "most economically advantageous tender"; and (iv) sending a notice in the appropriate form once the contract has been awarded.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.