Last month, RBS announced it is to increase its provisions by over GBP 3 billion in relation to investigations and litigation centred on the US residential mortgage-backed securities it underwrote.1 At the same time, the US DoJ has levied further fines exceeding USD 12bn on two European banks to settle claims of abuse within the RMBS market.2 On this backdrop, and prior to the 2016 reporting season, we thought it a suitable time to reflect on the level of provisions within European banking institutions and to explore whether the tide of regulatory penalties is starting to turn.

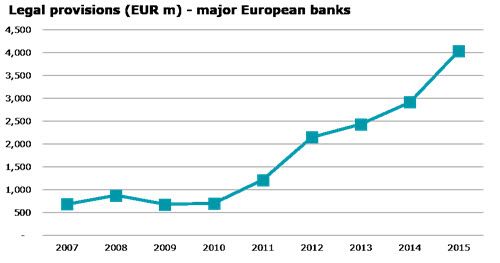

The graph below shows an increasing trend in the normalised average level of provisioning taken by ten3 of the largest European banks (by balance sheet size) in the wake of the financial crisis:

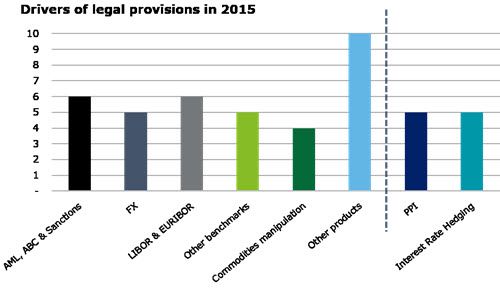

As the regulatory environment tightens, banks continue to increase the amounts put aside for regulatory penalties and legal disputes which may arise through allegedly inappropriate treatment of both retail and wholesale customers. By its nature, a provision is "a liability of uncertain amount or timing" and so management's judgement is required in assessing the likely future impact of the penalty/dispute. However, regardless of the size of the provision made, there are a number of recurring themes requiring provisioning across the European banks shown in the chart below:

While mis-selling (PPI and interest rate hedging) is an issue which affects the retail customer base, the other topics in the chart above predominantly concern banking behaviour when dealing with wholesale customers. These can potentially have a secondary waterfall effect on retail customers where losses resulting from manipulative or fraudulent acts lead to litigious actions being pursued against the banks, either by individuals or at a class action level. Consider, for example, the customer who believes his LIBOR-referenced loan payments were too high as a result of benchmark manipulation, or, say, a group of customers who feel aggrieved at having received poor rates when changing currency which they attribute to collusion over spot rate fixing.

Much of the provisioning which has occurred in recent years can be directly traced back to the financial crisis – being uncovered as a result of the change to the interest rate yield curve (e.g. interest rate hedging product mis-selling) or a tightening of available credit and a change in risk appetite (e.g. the collapse of the Madoff hedge fund) – or arose as a direct result of the requirements for banks to raise capital during the crisis (e.g. litigation by shareholders against RBS over the £12bn capital raising in 2008).

PPI is separate from this – a predominantly British phenomenon which has cost the banks in excess of £25bn since 2006 and which remains a key contributor to the posted provisions of home banks in the 2015 accounts.

One issue with analysing provisions is that any review naturally requires a backward glance at the past; however, to many the interest lies not in what provisions currently sit in a bank's accounts, but how they have adjusted their present work practices to avoid the danger of future reductions to the income statement. Regulators continue to try to close loopholes and to tighten the environment to discourage poor behaviour to prevent future misdemeanours – the introduction during 2016 of the Senior Managers and Certification regime being just one example. This is a further step on the road towards tighter regulation through greater individual responsibility and accountability – although few individuals remain to have been held to account for either their own actions or those of people for whom they were responsible.

Our predictions for the 2016 reporting season? Product mis-selling will remain on UK banks' agendas; and although the interest rate derivative mis-selling review should be complete from a basic redress point of view, we would expect the consequential loss claims to run on for some time yet. PPI will also remain a mainstay of UK provisioning, at least until the claim procedure is set to end in 2019.

Individual litigious disputes – new and legacy – will continue to pepper balances sheets both in the UK and in wider Europe, where we also wonder if (maybe not in the 2016 financial statements, but perhaps beyond) certain mis-selling provisions seen in the UK will spill over. The Dutch regulator in 2016 launched a review into the sale of interest rate derivatives to SME clients along the lines of the UK review...a sign of things to come across the rest of the continent?

It is over eight years since the height of the financial crisis; it should not be beyond the realm of credibility to imagine that related provisioning would have begun to have fallen off, however the expected further RMBS related penalties sparking RBS' recent provision increases might suggest that we are not out of the woods yet. Looking further ahead, an uncertain political landscape (Brexit, the inauguration of President Trump, and upcoming elections in France, the Netherlands and Germany) may be the source of future bank provisioning in ways which we cannot yet predict.

Footnotes

1 http://www.investors.rbs.com/~/media/Files/R/RBS-IR/results-center/20170126-rns.pdf

3 Based on the rankings provided by http://www.hitc.com/en-gb/2016/04/26/sp-global-market-intelligence-ranks-europes-50-largest-banks-by/. A bank in the top 10 has been replaced with another (11th largest) due to the data relating to legal provisions in the Bank's annual report not being comparable with the other banks in the population.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.