On March 22, 2019, CMS published a long-awaited letter to State Medicaid Directors and a new guidance document regarding the Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waiver program. The letter revises previous guidance that CMS had provided to states on "Settings that have the effect of isolating individuals receiving HCBS from the broader community" for purposes of receiving Federal funding for services provided under a HCBS waiver. The updated guidance follows years of intensive advocacy work by disability care providers, including advocates of lifesharing models and farmstead communities, that previous guidance had singled out as potentially problematic. Foley Hoag attorneys are proud of the work we did in helping to advance this cause and achieve success for our clients (you can read more about them here).

Background

The HCBS waiver program first became available in 1981 when Congress added section 1915(c) to the Social Security Act as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1981, giving States the option to receive a waiver of Medicaid rules governing institutional care. Prior to 1981, comprehensive long-term care services through Medicaid were available only in institutional settings. In enacting 1915(c), Congress anticipated that long-term care costs could be better contained if services were provided in less expensive home and community-based settings than in institutions.

The HCBS waiver program has gone through a number of changes since first enacted, broadening and expanding state flexibility in operating HCBS programs. As part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, HCBS became a formal Medicaid state plan option, allowing states to offer HCBS under a Medicaid state plan, rather than seeking a waiver.

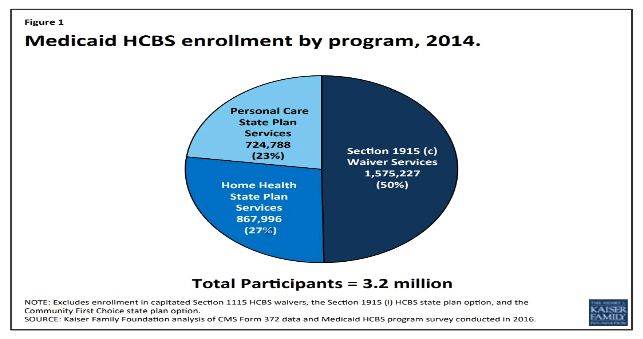

Today, HCBS services are available to states under a variety of mechanisms depending on the treatment population, including: 1915(c) [HCBS Waiver], 1915(i) [State Plan Home and Community based Services], and 1915(k) [State Plan Community First Choice Option]. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, nearly 3.2 million people received services through the three main Medicaid HCBS programs in 2014.

2014 Final Rule

On January 10, 2014, the Obama Administration published in final rulemaking a significant update to the requirements for the qualities of settings eligible for reimbursement for Medicaid HCBS provided under sections 1915(c), 1915(i) and 1915(k) of the Medicaid statute. The rulemaking emerged in partial response to a 1999 Supreme Court Decision (Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581) in which the Supreme Court affirmed a state's obligations to provide covered program services to eligible individuals with disabilities in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs. As a result of the 2014 Final Rule, CMS adopted new minimum standards that all HCBS setting must meet, including that the setting:

- The setting is integrated in and supports full access to the greater community;

- Is selected by the individual from among setting options;

- Ensures individual rights of privacy, dignity and respect, and freedom from coercion and restraint;

- Optimizes autonomy and independence in making life choices; and

- Facilitates choice regarding services and who provides them.

While explicitly excluding certain settings as permissible for HCBS services (for example, nursing facilities and institutions for mental disease), the final rule also identified other settings that are presumed to have "institutional qualities," and thus do not meet the threshold for Medicaid HCBS (for example, those that have the effect of isolating individuals from the broader community of individuals not receiving Medicaid-funded HCBS). In regulation, CMS noted that services would be subject to a "heightened scrutiny" process should states wish to offer them:

Any setting that is located in a building that is also a publicly or privately operated facility that provides inpatient institutional treatment, or in a building on the grounds of, or immediately adjacent to, a public institution, or any other setting that has the effect of isolating individuals receiving Medicaid HCBS from the broader community of individuals not receiving Medicaid HCBS will be presumed to be a setting that has the qualities of an institution unless the Secretary determines through heightened scrutiny, based on information presented by the State or other parties, that the setting does not have the qualities of an institution and that the setting does have the qualities of home and community-based settings. 79 Fed. Reg. 2948, 3034 (January 16, 2014).

Following publication of the final rule, CMS issued a guidance document entitled, "Guidance on Settings that have the Effect of Isolation Individuals Receiving HCBS from the Broader Community," to advise states on the heightened scrutiny process. It is this Guidance document that is the subject of today's blog post.

2014 Guidance on Settings that have the Effect of Isolation Individuals Receiving HCBS from the Broader Community

Following publication of the 2014 Final Rule, and in response to state questions regarding the scope of settings that have the effect of isolating individuals from receiving HCBS from the broader community (and thus subject to "heightened scrutiny" standard), CMS published a guidance document which took a broad view of such settings. First, CMS provided two overarching characteristics of settings that isolate (noting that having one of these characteristics, alone, may cause the setting to meet the isolation standard):

- The setting is designed specifically for people with disabilities, and often even for people with a certain type of disability.

- The individuals in the setting are primarily or exclusively people with disabilities and on-site staff provides many services to them.

Next, CMS listed three additional characteristics of settings that may isolate people receiving HCBS from the broader community:

- The setting is designed to provide people with disabilities multiple types of services and activities on-site, including housing, day services, medical, behavioral and therapeutic services, and/or social and recreational activities.

- People in the setting have limited, if any, interaction with the broader community.

- Settings that use/authorize interventions/restrictions that are used in institutional settings or are deemed unacceptable in Medicaid institutional settings (e.g. seclusion)

Finally, based on these characteristics, CMS identified a non-exhaustive list of examples of residential settings that typically have the effect of isolating people receiving HCBS from the broader community:

- Farmstead or disability-specific farm community

- Gated/secured "community" for people with disabilities

- Residential schools

- Multiple settings co-located and operationally related that congregate a large number of people with disabilities together and provide for significant shared programming and staff

As a result of this guidance document, communities relying on any of the above settings were immediately concerned about the future of their Federal funding. In particular, rural, farmstead communities relying on a "lifesharing" model of care were particularly concerned about their future Federal funding given the scrutiny applied to such communities. In its Guidance, CMS wrote of these communities:

Farmstead or disability-specific farm community: These settings are often in rural areas on large parcels of land, with little ability to access the broader community outside the farm. Individuals who live at the farm typically interact primarily with people with disabilities and staff who work with those individuals. Individuals typically live in homes only with other people with disabilities and/or staff. Their neighbors are other individuals with disabilities or staff who work with those individuals. Daily activities are typically designed to take place on-site so that an individual generally does not leave the farm to access HCB services or participate in community activities. [...]. While sometimes people from the broader community may come on-site, people from the farm do not go out into the broader community as part of their daily life. Thus, the setting does not facilitate individuals integrating into the greater community and has characteristics that isolate individuals receiving Medicaid HCBS from individuals not receiving Medicaid HCBS."

In response, advocates of lifesharing models began to mobilize at CMS, on Capitol Hill, and at the White House advocating for the importance of choice for individuals living with disabilities. During this effort, Tom Barker and I had the fortunate experience of getting to know one of these communities — Camphill Village in Copake, NY.

At Camphill, on 615 acres of wooded hills, gardens, and pastures in rural upstate New York, adults with special needs and long- and short-term service volunteers strive to live and work together in extended families in homes throughout the Village. We had the opportunity to visit Camphill, to meet their residents and staff, and even to assist and advise in their advocacy efforts at CMS, on Capitol Hill, and at the White House. During these advocacy efforts, we explained the problematic impact of the 2014 Guidance Document and the threat it posed to Camphill and other communities relying on a lifesharing model.

2019 Updated Heightened Scrutiny Guidance

In response to these advocacy efforts, and in line with CMS Administrator Seema Verma's letter to Governors on March 14, 2017, on March 22, 2019 CMS issued an updated guidance and set of FAQs revising and replacing, in large part, its previous guidance on the heightened scrutiny standard and settings that have the effect of isolating individuals from the broader community. Overall, the guidance takes a much more holistic view at such communities, providing states with greater flexibility to promote choice and identify the setting that is right for the individual. Of note, CMS re-wrote the list of factors/characteristics which the agency will take into account in determining whether a setting may have the effect of isolating individuals receiving HCBS from the broader community:

| Previous Guidance

|

New Guidance

|

| The setting is designed specifically for people with disabilities, and often even for people with a certain type of disability. | Due to the design or model of service provision in the setting, individuals have limited, if any, opportunities for interaction in and with the broader community, including with individuals not receiving Medicaid-funded HCBS. |

| The individuals in the setting are primarily or exclusively people with disabilities and on-site staff provides many services to them. |

The setting restricts beneficiary choice to receive services or to engage in activities outside of the setting. |

| Settings that isolate people receiving HCBS from the broader community may have any of the following characteristics:

|

The setting is physically located separate and apart from the broader community and does not facilitate beneficiary opportunity to access the broader community and participate in community services, consistent with a beneficiary's person-centered service plan. |

Of particular note, not only did CMS completely modify the criteria of isolating settings, it also removed the examples of settings that may have isolating effects (in other words, rural or farmstead communities are no longer, per se, subject to heightened scrutiny.)

In addition, CMS added a new FAQ addressing HCBS settings in rural communities, opening up the possibility that such settings need not be subject to a heightened scrutiny process:

Settings located in rural areas are not automatically presumed to have qualities of an institution, and more specifically, are not considered by CMS as automatically isolating to HCBS beneficiaries. CMS also instructs States that they should only submit a specific setting for a heightened scrutiny review if the setting has been identified as presumed to have qualities of an institution, and if the state believes that the setting has overcome the presumption. With respect to determining whether a rural setting may be isolating to HCBS beneficiaries, states should compare the access that individuals living in the same geographical area (but who are not receiving Medicaid HCBS) have to engage in the community.

While the result of much of this guidance will still depend on state negotiations with these communities, CMS has now freed states to determine how best to service HCBS populations. For many individuals, a rural, lifesharing model may be the best model for their personal needs. CMS has now removed barriers that could have prevented this type of setting from remaining available to individuals living with disabilities.

To view Foley Hoag's Medicaid and the Law blog please click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.