This article was previously published in Les Nouvelles: The Journal of Licensing Executives Society.

I. INTRODUCTION

This paper describes the increasing importance of economic and financial analysis in determining the value of intellectual property—and of patents in particular—in the U.S. courts. We observe that patent damage awards by the courts are now commonly based on careful economic and financial analysis. As a result, patent owners today are better able to satisfy the courts' requirements for demonstrating damages in a non-speculative manner than in the past. Patent owners have been able, either by winning in court or more commonly through favorable settlement of litigation, to obtain compensation from infringers and protect the value of their patents. This contrasts with previous eras when patent owners were often limited in claiming damages to testimony based on anecdotal evidence or questionable rules of thumb. We discuss implications of this trend, both in the courtroom and in general perceptions of the value of intellectual property.

Until the situation was changed beginning in the 1980s, primarily as a result of the decisions of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the "Federal Circuit"), successful patent owners in U.S. Courts were restricted in their ability to obtain adequate damage awards for losses suffered as a result of patent infringement. Precedent limited the range of admissible evidence about damages, especially those resulting from lost profits. However, during the past two decades, a series of court decisions changed the situation. Now, patent owners have the ability to present well-supported evidence about their losses when damages are to be considered. Accused infringers too can and do use reasoned analysis to protect themselves from excessive claims. Economic and financial experts are now used in almost all patent matters by both sides. Evidence is offered to (and sometimes solicited by) the courts, on the structure of markets in which the patented products are used, the actual and expected profitability of the parties and others in the industry, and on related matters of price elasticity, barriers to entry and the derived demand for the products involved.1

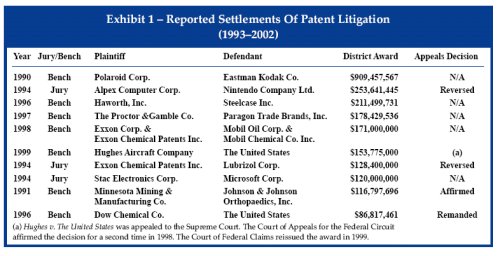

It is commonly believed that these developments favored patent owners and that they led to an increase in the size and number of patent damage awards in the 1980s and 1990s. The often-cited example of this trend is Polaroid's $900 plus million award in 1990 against Kodak for patents related to instant photography products.

Critics of this trend voiced fears that this perceived pro-plaintiff bias would have a chilling effect on innovation in the economy, as potential innovators would tend to shy away from introduction of new products and technology fearing protracted and expensive litigation that could wipe out the value of such investments. However, since 1990 there have been no new awards approaching the size of Polaroid's and the evidence presented in this paper indicates that there has not been a trend toward higher awards for plaintiffs. This trend appears to be explained by two factors. There has been an increase in the already extensive use of settlements rather than litigating to the death as a way of ending patent disputes. In addition, with the permission and support of the courts, defendants have answered plaintiffs, by incorporating economic and financial arguments into their defenses at least in part, offsetting any tendency toward excessive awards.

II. PATENT LITIGATION AND DAMAGE AWARDS

Exhibit 1 lists the ten largest patent damage awards received by patent-owners in U.S. district courts since 1990. Prior to 1990 there had been only one patent damage award in history larger than $100 million.2 Since 1990 there have been nine. In addition, several jury verdicts later overturned by trial judges reached triple digits. One such verdict broke the billion dollar barrier—a $1.2 billion verdict in 1995 for Litton Industries against Honeywell. In recent years, the number of jury verdicts overturned by district court judges appears to be on the increase. In 2002, three such actions overturned verdicts of $140 million, $271 million and $324 million.3

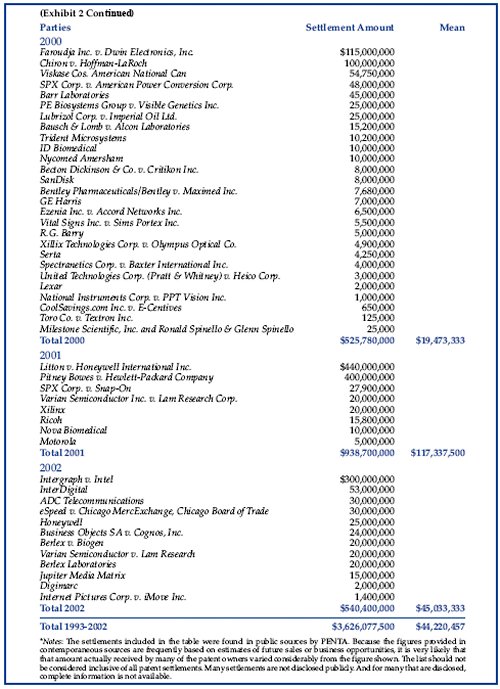

A number of other patent owners gained significant payments from claimed infringers as a result of settlements of patent litigation. Our analysis of data from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts showed that since 1993, 63% of patent cases were disposed of by settlement prior to a district court decision.4 By comparison, only 35% of all civil cases were settled. A number of the patent settlements have reached amounts that would rank with the largest damage awards. Since 1993, we found eleven settlements of patent disputes in which plaintiffs were reported to have received at least $100 million.5 (See Exhibit 2.)

These large awards, verdicts and settlements make headlines and, perhaps because of them, there has been a boom in patent litigation. The number of patent cases filed annually more than doubled between 1991 and 2001, rising from 1,178 to 2,520.6 The number of patent cases terminated in a given year has also increased but at a lower rate. Thus, the backlog or the number of patent cases pending went up from 1,715 in 1991 to 2,923 in 2000.7 (See Exhibits 3 and 4.)

The number of patent cases pending has risen at a much faster pace than the number of non-patent cases pending. The number of patent cases pending grew by about 70% over the years 1991-2001. The number of non-patent civil cases pending grew by only 5% over the same period (from 238,884 in 1991 to 250,012 in 2001).8

There have been many reasons suggested for the increased size of awards and the related growth in patent litigation. Two in particular are persuasive. On the legal side, the creation in the early 1980s of the Federal Circuit was thought by many to have aided patent owners. Formation of the Federal Circuit ensured that specialized judges, most with technical training, would hear all appeals in patent cases. Previously, patent cases were treated in the federal courts the same as any other type of litigation and appeals were heard by circuit courts around the country. Presumably the expert jurists on the Federal Circuit would not be as put off as many circuit court judges were thought to be by the inherent complexities of highly technical patent matters, or by the often daunting task of considering damages in situations where the but-for world, absent the infringer's actions, was far different than the actual world. In addition, judges with backgrounds in patent law may have been less likely than other jurists to see a contradiction between the monopoly rights granted to an owner of intellectual property and the traditional legal abhorrence of monopoly in the antitrust law tradition.

Changes in the economy are also likely to have contributed to the increasing importance of patent rights. The development in recent decades of entirely new information-based industries and the transformation of older ones—biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, personal computers, the Internet and wireless communications— has certainly increased the importance of ideas relative to that of physical assets. So, it should not be surprising to see an increase in the number of ownership disputes and claims of trespassing on these valuable property rights.

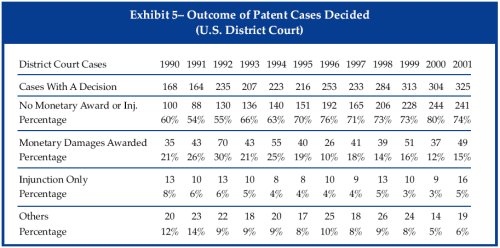

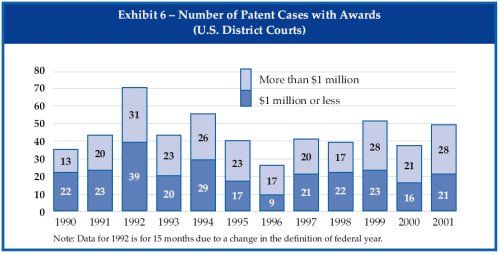

We analyzed data from the ICPSR showing the trend in the number of damage awards and the frequency of large awards from 1990 through 2001.9 The data shows that the number of patent cases with a damage award has stayed relatively steady for the period 1990 through 2001. However, in percentage terms it has declined significantly. Over the first three years (1990-92), 26.1% of the decisions had monetary awards. In the most recent three years the percentage fell to 14.7%. Further, the number and percentage of small damage awards (defined as $1 million or less) has increased over the period. Awards of $1 million or less were only 37% of all damage awards in 1990, and only 43% of all awards from 1990 through 1992. However, since 1999, 56% of all awards were for $1 million or less. (See Exhibit 5.)10

In the following sections, we discuss changes in the acceptance of economic and financial theory and analysis by the courts as evidence when evaluating patent damages. In the context of other changes in the law and the economy, the increased willingness of the courts to hear such evidence, and not to reject it out of hand as too speculative, has played an important role in the increase in the value of intellectual property to injured patent owners. Such acceptance has, however, also allowed accused infringers to present reasonable defense against extravagant damage claims.

III. INCREASING USE OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS AND FINANCE IN CONSIDERING PATENT DAMAGES

In litigation, patent owners generally seek monetary damages as compensation for the economic harm done by an infringer.11 The Patent Act describes the basis of an award for compensatory damages as follows:

Upon finding for the claimant the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement, but in no event less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer, together with interest and costs as fixed by the court.12

A. Lost Profits

The most common type of damages claimed by patent owners who are actively engaged in business using the patent involve profits lost when an infringer unfairly competes with the patent owner causing lost sales and price erosion. Despite the explicit wording of the law, historically patent holders were limited in their ability to obtain lost profit damages. The courts applied very restrictive rules to avoid what were considered to be excessively speculative claims that the patent owner would have made the infringer's historical sales had the infringer not been competing with an infringing product. As a result, by far the most common type of award was the default "reasonable royalty" specified in the law.13

The classic statement of the factors considered by the courts in deciding whether to allow lost profits appeared in the Panduit decision in 1978 (Panduit Corporation v. Stahlin Brothers Fibre Works, 575 F.2d 1152, 197 USPQ 726, 6th Cir. 1978). Courts still frequently consider the four factors stated in Panduit when determining the appropriateness of a lost profits damage claim. Under the four Panduit factors, proof of lost profits involved demonstration of:

- the existence of demand for the patented technology;

- the absence of non-infringing substitutes;

- the patent owner having adequate production, marketing and distribution capacity to make the additional sales; and,

- the claimant's ability to estimate the amount of lost profits in a reasonable or non-speculative manner.

The second Panduit factor (absence of non-infringing substitute) turned out to be the most limiting factor in granting of lost profits. It was frequently held that existence of any non-infringing substitute for a patented product was the basis to dismiss the lost profits claim of the patent–holder. That is, it was considered that the existence of a non-infringing substitute was enough to prevent the patentee from proving in a non-speculative way the amount of any lost profits caused by the infringement.

Such restrictions were clearly too limiting. As a result, patent owners were being denied adequate recovery. In the early 1980s, with the leadership of the new Federal Circuit, the courts began to change by incorporating economic analysis in their deliberations.

TWM was an important early case. It involved decisions on damages by both the Federal Circuit and the district court. In the end, the patent owner received damages of both types—reasonable royalties on a portion of the infringer's sales and lost profits on others (TWM Mfg. Co., Inc. v. Dura Corp., 231 USPQ 525 (D.C. E.D. Mich. 1985), and TWM Mfg. Co., Inc. v. Dura Corp., 789 F. 2d 895, 229 USPQ 525 (Fed. Cir. 1986)). These decisions made use of a number of important methodologies in estimating damages. Notably for the present discussion, the decisions allowed plaintiff to receive some lost profits even in the face of claims that non-infringing substitutes were present in the market. The TWM Court noted evidence of the existence of alternatives to the patented product. However, the Court allowed lost profit damages, recognizing evidence that the alternatives were not perfect substitutes for the patented products.

The position of the patent owner was improved again with the Mor- Flo decision in 1989. In that case, a method of analysis was explicitly approved to determine the amount of a lost profits award even in the presence of acceptable non-infringing substitutes (State Industries, Inc. v. Mor-Flo Ind. Inc., 883 F. 2d 1573, 1577-78 (Fed. Cir. 1989)).

In this case, the Federal Circuit allowed an award of lost profits damages based on the market share of the patentee, an approach that explicitly recognized the presence of non-infringing substitutes. The following example illustrates how the Mor-Flo market share analysis is implemented, and how a patent owner can be awarded lost profits even in the presence of non-infringing substitutes.

Illustration

The market in which the patented invention is used is assumed to have annual sales of 100,000 units.

In the damages period there were four suppliers in the market.

Manufacturer 1 is the patent owner and sells 35,000 units annually.

Manufacturer 2 and Manufacturer 3 produce acceptable non-infringing alternatives and sell 25,000 units each.

Manufacturer 4 is the infringer and sold 15,000 units.

The historical market shares are:

|

Manufacturer 1: |

35,000 |

(35%) |

|

Manufacturer 2: |

25,000 |

(25%) |

|

Manufacturer 3: |

25,000 |

(25%) |

|

Manufacturer 4: |

15,000 |

(15%) |

|

Total |

100,000 |

(100%) |

The market shares in the "but for" situation are:

|

Manufacturer 1: |

35,000 |

(41.18%) |

|

Manufacturer 2: |

25,000 |

(29%) |

|

Manufacturer 3: |

25,000 |

(29%) |

That is, based on Mor-Flo market share analysis, the patent owner would claim lost profits on approximately 41% of the sales of the infringer. The patent owner would generally be able to claim reasonable royalties on the remaining 59% of the infringer's sales.

TWM and Mor-Flo established the principle that a claim for lost profits would not necessarily be precluded by the presence of the non-infringing alternatives. As a result, patent owners today often regard the market share based on Mor-Flo as a floor in determining lost profit damages. Although, depending upon the market conditions, (for example, the degrees of substitution between patent owner's product, infringer's product, and other non-infringing products), the patent owner can sometimes claim more than the share based on Mor-Flo analysis.

However, defendants have responded successfully to such claims by plaintiffs and are often able to prevent damage awards from being based on a mechanical application of the Mor-Flo approach. Defendants regularly use fact and expert testimony to show that the market shares put forward by plaintiff may not be indicative of what sales plaintiffs would have had in a but-for world. In many cases the most important factor in determining the size of a prospective award is the outcome of a complex analysis of market conditions and the factors affecting elasticity of demand for the patented product.

B. Reasonable Royalty

In instances where lost profit damages are not present or are deemed not provable on some or all of their infringing sales, the law is explicit that the patent holder is, at a minimum, entitled to a reasonable royalty when infringement is found. Even in today's environment, which is more permissive with respect to lost profits claims than had been the case previously, more than half of all damage awards include only reasonable royalties.14

The most common method for estimating the amount of a reasonable royalty is to assess the result of a hypothetical negotiation between the parties, prior to the infringement. The hypothetical negotiation is analyzed based on the expectations and knowledge that the parties would likely have had at the time. This assessment calls for the analysis of a wide range of economic and financial conditions and market and cost accounting data. In what has come to be a widely cited checklist of factors that might be considered in determining a reasonable royalty, the district court in Georgia- Pacific listed the following 15 factors.15

The Georgia-Pacific Factors:

- The royalties received by the patentee for the licensing of the patents in suit, proving or tending to prove an established royalty

- The rates paid by the licensee for the use of other patents comparable to the patents in suit

- The nature and scope of the license, as exclusive or non-exclusive; or as restricted or non-restricted in terms of territory or with respect to whom the manufactured product may be sold

- The licensor's established policy and marketing program to maintain its patent monopoly by not licensing others to use the invention or by granting licenses under special conditions designed to preserve that monopoly

- The commercial relationship with the licensor and the licensee, such as, whether they are competitors in the same territory or in the same line of business, or whether they are inventor and promoter

- The effect of selling the patented specialty in promoting sales of other products of the licensee; the existing value of the invention to the licensor as a generator of sales of its non-patented items; and the extent of such derivative or convoyed sales

- The duration of the patent and the term of the license

- The established profitability of the product made under the patent; its commercial success; and its current popularity

- The utility and advantages of the patent property over the old modes or devices, if any, that had been used for working out similar results

- The nature of the patented invention; the character of the commercial embodiment of it as owned and produced by the licensor; and the benefits to those who have used the invention

- The extent to which the infringer has made use of the invention; and any evidence probative of the value of that use

- The portion of the profit or of the selling price that may be customary in the particular business or in comparable businesses to allow for the use of the invention or analogous inventions

- The portion of the realizable profit that should be credited to the invention as distinguished from non-patented elements, the manufacturing process, business risks, or significant features or improvements added by the infringer

- The opinion testimony of qualified experts

- The royalty that a licensor (such as the patentee) and a licensee (such as the infringer) would have agreed upon at the time the infringement began if both had been reasonably and voluntarily trying to reach an agreement; that is, the amount which a prudent licensee—who desired, as a business proposition, to obtain a license to manufacture and sell a particular article embodying the patented invention—would have been willing to pay and the amount that would have been acceptable to a prudent patentee who was willing to grant a license.

As the list indicates, the Court invited an explicit analysis of economic and financial evidence in order to determine the amount of the reasonable royalty. However, for many years, in practice, establishment of a reasonable royalty was based less on such analysis than on war stories and rules of thumb. In a typical case, each side had an old industry hand or licensing expert who would testify that, based on personal experience, the appropriate royalty would be a certain percentage of sales or profits. Often, the testimony would refer to general rules of thumb—such as the well known "25% rule"—which often appear to have no factual basis other than the continued citations to them.16

One prominent observer criticized the practice of setting royalty rates by listening to the unverifiable testimony of old hand experts as the being part of "...those good old days of yesteryear when out of the dust rode 'expert opinions' based on illogical speculation and the hypothetical negotiations degenerated into conjuring up 'Ghosts of Christmas' past.17 The spectral reference is to the appeals court decision in Panduit. In that decision the court adopted a version of what later came to be referred to as the analytical method for establishing a royalty and referred to the, then common, practice—the 'Ghosts' method—as a 'legal fiction.' "18

With the use of sound analytical techniques, the courts began to recognize the need for more concrete analysis of the factors that would have influenced reasonable parties when negotiating the hypothetical license. There have been a number of variants of the analytical approach applied since Panduit and TWM. However, the approaches have in common an evaluation of the positions of the hypothetical licensor and licensee. The analysis involves calculating the prospective returns to the patent owner/licensor from allowing a licensee to use the patent, and the comparison of those returns with the owner's other opportunities for exploiting the patent. For the licensee/infringer, determination is made of the profits reasonably anticipated from using the patent compared with those available from relevant alternatives.

An analytical approach allows determination of a range of royalties that would be acceptable to a reasonable licensor and a reasonable license. The range is typically narrowed to a single amount by adjusting the range to account for factors specific to the case and the parties. Adjustments might involve an analysis of the relative bargaining power of the parties, their past experiences with licensing- in or licensing-out, their financial and technical capacities and the strategic opportunities or challenges they might face in the relevant market and any markets that are related. More generally, using a proper approach to estimating a reasonable royalty in the current environment involves considering the condition and expectations of the parties at the time of infringement.19

IV. CONCLUSION

Our analysis of the patent lawsuits decided in the U.S. district courts and by the Federal Circuit shows that application of economic and financial analysis in determining the proper amount of damage awards in patent litigation has been increasing, over the last two decades. We have also observed a significant increase in the amount of patent litigation, although not necessarily in the number or size of damage awards. As the trend toward increasing use of analytical evidence has continued, we believe that it has contributed to creation of a better framework for establishing the economic value of patents. Patent owners have a more reasonable chance of obtaining adequate relief in the face of infringement, while defendants have been able to prevent unreasonable awards by presenting objective evidence based on economic and financial analysis.

Up-to-date information on this subject is available from Dr. Prakash-Canjels at ARPC.

Footnotes

1. Federal Circuit Judge Randall Rader provided an indication of the importance the Courts now place on proper economic and financial analysis when he suggested that district court judges should "...demand from your experts...testimony as to the sensitivity of quantity to price factors in the market place." He further suggested, perhaps exaggerating, that district court judges should "...exclude from your damage trials any expert who tries to base his damage calculation on anything other than a downward sloping demand curve." (Speech to the Annual Meeting of the Licensing Executives Society, Miami, 1998.)

2. Smith International, Inc. v. Hughes Tool Co., 229 USPQ 81 (C. D. California, 1986).

3. "Should You Settle After the Jury's Done?", Riley, Michele M. and Jackson, Donald L., The Patent Journal, November 2002.

4. The data created for Administrative Office of the Courts is reported in Study #8429 produced by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research ("ICPSR"). It includes information on all cases filed and terminated in federal district courts. Citations herein to ICPSR represent data extracted from Study #8429 and #3415 by the authors. The most recent data available from the ICPSR includes 2001 for cases filed and through 2000 on cases terminated.

5. The data in Exhibit 2 is taken from a database of patent damage awards and settlements maintained by PENTA Advisory Services. The reported amounts are taken from public sources. Often the reported amounts contain contingencies that could result in final payments quite different from those reported.

6. ICPSR Study #8429.

7. The data compiled by ICPSR also lists patent cases that are pending each year. Note that the number of cases pending (or terminated) in any year includes cases filed in prior years.

8. ICPSR Study #8429 and #3415.

9. The data for 2001 is the most recent available from ICPSR.

10. ICPSR Study #8429 and #3415.

11. In many patent cases damages do not become an issue. Instead, a patent owner might be in a position to stop a potential infringer before significant damage is done by obtaining an injunction. Injunctions are also commonly sought in cases involving damages.

12. 35 USCA§ 284.

13. Reasonable royalty awards are still more common than lost profits awards. The PENTA database shows that since 1990, 53.9% of all district court patent damage awards were reasonable royalties, 28.6% were based entirely on lost profits and 17.5% combined both elements of damages. In situations where the owner and the infringer are not competitors, lost profits claims are not usually made.

14. Data collected by PENTA on reported patent damage awards from 1990 through 1999 show that 54.4% of all awards contained only reasonable royalties.

15. Georgia-Pacific v. United States Plywood Corp., 318 F. Supp. 1116. (I.S.D.N.Y. 1970).

16. Of course, after continued citations to them such rules begin to have relevance even if originally there was none.

17. Myers, Geoffrey R., "Damages" at B.35, in Patent Infringement Remedies, Patent Resources Group, Charlottesville, VA, 2000.

18. Panduit Corp. v. Stahlin Bros. Fibre Works, 575 F.2d 1152, USPQ 726 (6th Cir. 1978).

19. The courts have long directed that the hypothetical negotiations for determining a reasonable royalty should be deemed to have taken place just prior to the date of first infringement. Although, in some situations when evaluating the royalty amounts the parties may be permitted to use information that would not have been known at the time of the hypothetical negotiations. See, for example Fromson v. Western Litho, 853 F. 2d 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.