This post describes a quantitative analysis of the use of consumer perception surveys to interpret implied advertising claims in the past five years of cases before the National Advertising Division of the Council of Better Business Bureaus (NAD), which I presented at the NAD Survey Conference in New York on December 7.

How Many Surveys Does NAD Receive – and Accept?

NAD is America's leading industry self-regulatory forum for resolving competitor disputes over false advertising. As I noted in my post on the past year's NAD cases, NAD adjudicates about 90 cases per year, most of them brought by national brands accusing their competitors of false or unsubstantiated advertising claims. Many of the challenged marketing claims are not literally stated in the advertisements, but allegedly are implied. Either party to a NAD proceeding may introduce survey evidence that the alleged claim either is or is not implied by the contested advertising.

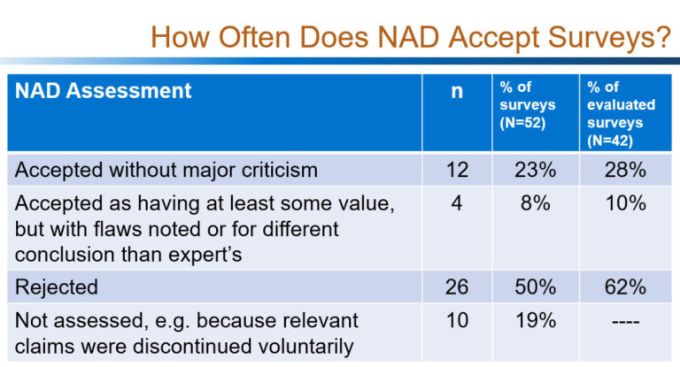

At the NAD Survey Conference I reviewed the 52 surveys submitted in 36 NAD cases (out of a total of 480 reported cases) in the past five years. I first wanted to know how often NAD accepts these surveys as valid, versus how often it finds too many methodological flaws for the survey to be useful. As you can see in the table above, I found that NAD is about twice as likely to reject a survey outright as it is to accept the survey as evidence of the existence of an implied claim. This isn't surprising to experienced NAD practitioners, but it is still remarkable. The experts who conduct surveys for NAD participants are experienced, highly regarded professionals. It isn't clear whether these experts are doing uncharacteristically bad survey work in NAD cases, or whether NAD is an especially tough – or idiosyncratic – grader of surveys.

Do Surveys Affect NAD's Decision?

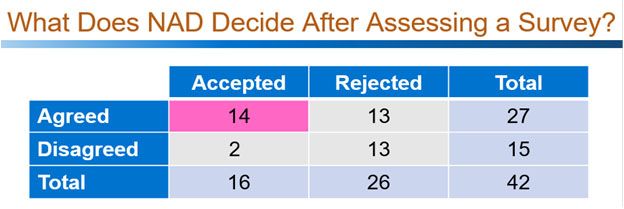

I next wanted to find out whether surveys seem to affect how NAD decides on the issue of whether the challenged claim really is implied by the advertising. Because most surveys evaluated by NAD are rejected, I also was interested in the relationship between NAD's evaluation of surveys and whether NAD nonetheless agreed with their conclusions.

When I coded the cases and ran the numbers, I found out that when NAD rejects a survey as invalid, it is still about equally likely to agree with the survey as to disagree, based on its independent review of the advertising. On the other hand, in cases where NAD accepts a survey as valid, it almost always agrees with the survey's conclusion about the implied claim.

So there is a correlation at NAD between accepting a survey as evidence and agreeing with its conclusion, but what does this mean? Is a valid survey so powerfully convincing to NAD that NAD hardly ever disagrees with its conclusion, or is NAD more likely to accept a survey when NAD has already made up its mind, adding additional support to a conclusion it would have reached anyway? To get some insight into this question, I had to switch from quantitative analysis to a close reading of the cases, to see if NAD spells out its thought process.

What I learned did not furnish much evidence that surveys change NAD's mind about implied advertising claims. In 9 of the 14 cases where NAD accepted a survey and also agreed with its conclusion about the implied claim, NAD wrote something to the effect that it conducted an independent analysis of the advertising anyway, and the survey merely supported its own judgment. Sometimes, when the survey faced strong criticism from the opposing party, NAD averred that even if it were to discard the survey as fatally flawed, it would still reach the same conclusion about the advertising. The other five cases were ambiguous. There was no case where NAD wrote, for example, that while it initially disagreed with the survey's conclusion about implied claims, the survey changed its mind; or even that NAD was initially uncertain whether there was an implied claim, but a survey submitted by one of the parties pushed it over the line. Of course, these things could have happened, and NAD just might not have mentioned it. At the end of my presentation, I urged NAD to give surveys due credit if they are ever a decisive factor in NAD's decision, just so the parties know when they are worth the investment. I didn't exactly get a reply, so I'll be reading future NAD decisions closely to see if they acknowledge the importance of a survey in reaching a decision.

Implications for NAD Case Participants

The ultimate goal of my analysis, and of the whole conference, was to provide some guidance for parties to NAD proceedings about whether and how to submit surveys in NAD cases. Various panelists covered this topic from many angles, and the takeaways from my presentation aren't the complete answer. I did offer two principles.

First, if you submit a survey to NAD, make it a good one, and keep as closely as possible to the style of survey NAD prefers, to boost your survey's low odds of being accepted.

Second, integrate your survey with your legal and rhetorical argument, because surveys may do better at NAD when they coincide with NAD's own judgment. Don't expect a survey to turn NAD around when your theory of an implied claim is very counterintuitive and unlikely to be accepted in the absence of a survey. A survey is only part of what NAD looks at in evaluating whether an implied claim is made, and a survey is unlikely to carry that burden on its own.

Thanks to NAD and the participants for an informative and entertaining conference on December 7. I look forward to future NAD events that drill down into key issues like this that occur regularly in NAD cases.

This has been the first installment of an occasional series on this blog, "What I Said At ..." In this series, our blog authors will discuss highlights of recent talks we have given at conferences and other events.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.