The European Commission's leniency programme is vital to the detection, investigation and prosecution of cartels, and therefore to the Commission's effectiveness as a competition authority. Any threats to the success of the programme are to be taken seriously.

One such threat is the rise of private antitrust litigation in Europe. It has created a new normal in which infringement decisions almost always result in follow-on private litigation. This has had a material impact on the way cartel members assess whether or not to apply for leniency. Therefore, an apparent fall in the number of immunity applications to the Commission has prompted discussion as to whether private litigation is to blame,1 and if so whether the Commission should be concerned.

A link between the rise of private litigation in Europe and fewer immunity applications is open to debate. Nevertheless, the Commission has taken prudent steps to maintain detection rates and incentives for immunity applicants. The more likely consequence of the rise of private litigation is that other cartel members, which have missed out on immunity, will feel less inclined to apply for leniency given the uncertain value of a percentage reduction in fine. If so, the bigger concern for the Commission could be the need to accept a greater investigative burden, and greater reliance on investigative tools such as large-scale document reviews.

The Commission's leniency programme

The Commission's leniency programme is the jewel in the crown of EU antitrust enforcement, because it achieves dual aims of detecting cartel conduct, and successfully investigating and prosecuting that conduct:

- A vital tool for detecting cartels – leniency incentivises the self-reporting of cartel conduct with the prospect of immunity from fines.2 As cartel fines increased following the introduction of the Commission's 1998 and 2006 fining guidelines, so too did the incentive. Today, fines regularly run into hundreds of millions of euros. As a consequence, immunity from fines is a powerful draw for cartelists and a destabilising influence on cartels. Therefore, leniency has become a vital detection tool for the Commission.

- A rich source of information and incriminating evidence – the leniency programme also helps the Commission to investigate and prosecute cartels in a number of ways. It is often the trigger for unannounced inspections, a potentially rich source of incriminating evidence. Cartel members that miss out on immunity may still benefit from a reduction in fine if they present evidence to the Commission that is of " significant added value ", and they will benefit from a higher percentage reduction the stronger the evidence they provide.3 In addition, leniency requires continuous cooperation and full disclosure from all applicants.4

These features and outcomes are built into the leniency process. So long as the Commission is receiving leniency applications, its investigative process will benefit from them. On the contrary, without the leniency programme, or with an inferior version of it, the Commission's enforcement activities would be seriously diminished.

The rise of private litigation in Europe has changed the leniency calculus

Any threats to the success of the leniency programme are therefore to be taken seriously. Recently, the main threat to EU leniency has been the rise of private antitrust litigation in Europe, which has had a material impact on the way cartel members assess whether or not to apply for leniency.

Follow-on private litigation is the new normal

Historically in Europe, and in contrast to the US, antitrust enforcement was conducted almost exclusively by public authorities, as opposed to private parties that had suffered from the cartel. For example, according to one report, in 2006, 90% of antitrust enforcement in Europe was public and only 10% was private, whereas in the US the opposite was true – see Figure 1.5

Since then, various factors have contributed to a rise in private litigation, including: greater public awareness of antitrust laws as a result of higher fines and increased media coverage; case law and legislative reform, most notably the Damages Directive, which has clarified procedure and paved the way for private claims; and the rapid growth of claimant firms and litigation funding. As an example of this trend, a snapshot of the litigation landscape in January 2009 revealed 18 private damages actions in Europe, whereas the same snapshot in October 2016 revealed 70 such actions – a four-fold increase.6

As a result, there is a new normal in Europe in which antitrust infringement decisions by the Commission or Member State authorities will almost always result in follow-on private litigation.

The assessment of whether to apply for leniency is now more nuanced

This means that a would-be leniency applicant can no longer think simply in terms of how much it will save in potential fines. It must also consider the extent to which a leniency application will increase its exposure to damages litigation. Whereas previously the decision to apply for leniency was quasi-automatic, the assessment is now more nuanced, and requires a careful balancing exercise.

The starting point for this balancing exercise – the potential avoidance or reduction of fines – will of course depend on whether the cartel member is eligible for immunity from fines, or merely a reduction, which as noted above could be as little as 20% or less. The starting point could therefore affect the final assessment.

To be weighed against this potential benefit is the likelihood that leniency will increase an applicant's exposure to damages litigation:

- Detection of the cartel – if the cartel has not yet been detected, an immunity application will do just that, and likely prompt a Commission investigation. That will increase the likelihood of an infringement decision, which is public and binding on national courts, and therefore provides a basis for a follow-on private claim.

- Infringement decision more likely – for those that find themselves the subject of a Commission investigation, a leniency application will strengthen the Commission's case against it. Of course, an unannounced inspection of the cartel member's premises might already have elicited incriminating evidence, and others might also present evidence implicating it. However, if there is any doubt as to a company's participation in the cartel, or the extent of its involvement, a leniency application will erase that doubt, and make an infringement decision against it more likely. As above, since an infringement decision provides a basis for a private claim, a leniency application increases the chances of such a claim.

- Limited ability to appeal – a leniency applicant's description of the nature and extent of its participation in a cartel, which forms part of the leniency statement,7 is not far from an admission of liability. In practice, an applicant's ability to appeal will be limited to contesting the calculation of the fine or, at most, the precise characterisation of the conduct. With one eye on private litigation, the inability to appeal a finding of liability may be unattractive. If an addressee of a Commission decision appeals a finding of liability, a private claim against that addressee will usually be stayed pending the outcome of that appeal. That could take years, and deter would be claimants. It may even cause claimants to omit a cartel member from the scope of the claim. For example, Scania is appealing the Commission's Trucks decision and has been left out of private claims in the UK.

- Roadmap for claimants – provides claimants with a roadmap to a successful claim and, potentially, to a larger claim than they might otherwise have brought. As noted above, an infringement decision provides a basis for a follow on private claim. If the scope of the infringement decision is wider than it would have been absent a leniency application, subsequent private claims could likewise be broader. Alternatively, the Commission might adopt a decision that is narrower than the true scope of the infringement refl ected in the leniency materials. If a claimant can get access to the leniency materials via disclosure, its claim might be broader than it would have been absent presentation of such evidence to the Commission. Access to those leniency materials might also improve a claimant's disclosure requests for other materials, and lead it to uncover similar misconduct beyond the scope of the leniency application, and therefore also result in a broader claim.

Should the Commission be concerned?

Recently, there has been some debate about whether the rise of private litigation in Europe – and therefore the new leniency calculus – means fewer cartel members are self-reporting, and whether the Commission's leniency programme is therefore under threat.

Much of the debate has focused on the impact of lower levels of self-reporting on the Commission's ability to detect cartels – the first main aim described above – given how reliant it is on immunity applications. Whilst a causal link between the rise of litigation and a fall in immunity applications is open to debate, the Commission has nevertheless taken prudent steps to address the threat.

The bigger concern is arguably the impact on the Commission's ability to gather evidence of a cartel – the second main aim described above. Whereas the incentives for immunity applicants are still strong, other cartel members could justifiably feel less inclined to apply for leniency, given that the reduction of fine could be as little as 20% or less.

A slight decline in the number of cartels being detected through leniency

Recently, there has been a noticeable fall in the total number of successful immunity and leniency applicants, with 46 in 2014, 32 in 2015 and 24 in 2016,8 and those numbers are often cited when debating the impact of private litigation on the Commission's ability to detect cartels.

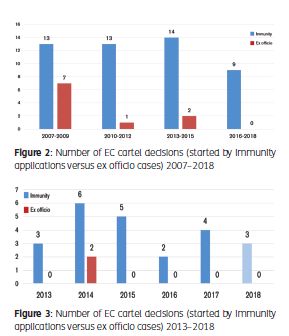

However, a better indicator of the leniency programme's detection capabilities is the number of immunity applicants. Figure 2 sets out the number of Commission decisions in the period 2007 to 2018 that were in respect of cartels detected exclusively through leniency. It also shows the number of decisions resulting from ex officio investigations. This suggests that in the last three years, albeit with some of 2018 still to run, there has been a fall in the number of immunity applications, compared to previous years. However, when looked at on an annual basis from 2013, the trend is less pronounced, especially considering that we are only half way through 2018 – see Figure 3.

The incentives for immunity applicants are still Considerable

Notwithstanding a slight fall in the number of immunity applicants, a causal link between that fall and the new leniency calculus is open to debate, because the incentives are still considerable. Indeed, it would be a brave general counsel who, having discovered their company's participation in an undetected cartel, chose to forego the prospect of immunity from a potentially huge fine.

Such a decision would imply: first, an estimation that damages will exceed the potential savings from immunity; second, an estimation that the Commission is unlikely to detect the cartel by other means; or a combination of the two. Whilst there may be circumstances justifying such a conclusion, it will not always be the natural one:

- Immunity versus damages – at the stage when the decision to apply for leniency is made, it is difficult to assess the likelihood and potential quantum of damages with confidence. There is also a lack of publicly available data to assess whether antitrust damages typically exceed the immunity saving, because parties tend to settle before or during trial. In addition, there are some recent high-profile cases where immunity applications appear, on balance, to have paid off handsomely. For example, in the Commission's interest rate derivatives cases, immunity applicants, including UBS and Barclays, avoided fines of hundreds of millions of euros,9 and to date there has been only one related private antitrust claim in Europe, by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Whilst that outcome might reflect case specific challenges of bringing a private claim on the facts,10 those cases nevertheless demonstrate the value that immunity can hold for cartel members.

- Likelihood of detection – it is true that the Commission relies disproportionately on leniency applications to detect cartels, as noted above. Since 2011, only two cartel decisions have been a result of ex officio investigations, both in 2014.11 Therefore, a cartel member might reasonably assess the risk of detection in the absence of a leniency application to be low, which is a precarious position for the Commission to be in. However, as demonstrated above, there has been a steady flow of immunity applications, even if slightly reduced recently. Therefore, and given the incentives for immunity applicants described above, a cartel member cannot safely disregard the risk of an immunity application by a co-conspirator, or conclude that the risk is materially less than it was previously.

The Commission has taken precautionary steps to maintain detection rates

The Commission's deputy director-general, Cecilio Madero, recently stated that the Commission is "not very worried" by the fall in leniency applications and suggested that such trends may be cyclical.12 Indeed, the leniency picture across jurisdictions is mixed, with some authorities reporting a fall, and others a rise in applications.13

Nevertheless, if there is even a creeping suspicion that cartelists are less inclined to self-report, a responsible authority will do all it can to demonstrate the continued risk of detection, and to minimise any disincentives associated with self-reporting, whilst protecting efforts to promote private enforcement.

This is no doubt the rationale for the Commission's decisions to devote more resources to ex officio investigations,14 and to introduce a whistleblower tool to encourage individuals to report cartel conduct, a move that opens up a new front against cartels.15 As noted above, the Commission remains fiercely protective of the confidentiality of leniency materials, and with the Damages Directive it has taken steps to reinforce the protection provided. The Damages Directive also enhances the incentives for immunity applicants by limiting claims by their co-conspirators for contributions to damages.16

If not evidence of Commission concern, these are the actions of a prudent regulator responding to a change in the legal landscape, and thereby seeking to maintain the efficacy of its enforcement activities.

The more likely consequence is reduced incentives for other cartel members

A more likely consequence of the new leniency calculus is that cartel members that have missed out on immunity will feel less inclined to apply for leniency. If so, this could impact on the Commission's effectiveness as a competition authority.

Historically, in the absence of private litigation, and faced with a Commission investigation, any reduction of fine was an attractive option, even for latecomers that might only get 20% or less. Today, when weighed against the likelihood of private litigation, the value of such a discount may be marginal at best. In addition, at the time the decision to apply for leniency is made, the value of any potential reduction is unclear:

- Percentage reduction – the percentage reduction is dependent on factors that are only partly within a party's control: the order in which a cartel member provides evidence of significant added value; and the quality of that evidence. In addition, the parties will not find out the final percentage reduction until the Commission's decision.

- Discount in absolute terms – the would-be applicant will not know what the percentage reduction represents in absolute terms until the total fine is confirmed, which is also not until the Commission issues an infringement decision.

As a consequence, a cartel member may see greater value in robustly defending the Commission's case, with the intention of avoiding or limiting the scope of an infringement decision against it, and deterring or hindering related private claims. Certainly, companies are well advised to pause for thought before deciding to apply for leniency.17

The bigger problem for the Commission could be a loss of enforcement efficiency and effectiveness

If the second thoughts of cartel members are translating into fewer leniency applications, the Commission's job of investigating and prosecuting cartels will be made more difficult:

- Greater reliance on investigative steps – the Commission would miss the orderly presentation of information and evidence that comes with a leniency application. It would increase its reliance on the applications of other parties or its own investigative steps, including unannounced inspections, large-scale document reviews via announced inspections, and requests for information.

- Reduced efficiency – it could also face more resistance from parties under investigation, which would impact on the efficiency with which the Commission can conclude an investigation. In particular, it might mean: fewer cases eligible for the settlement procedure; stiffer opposition to the statement of objections and at the oral hearing; and an increased likelihood of appeals.

- Less enforcement – fewer leniency applications and more resistance could also result in fewer infringement decisions or decisions that are narrower in scope, and thereby reduce the Commission's effectiveness as a competition authority.

It is possible that the Commission would accept such outcomes as a necessary consequence of the rise of private enforcement – a trend that the Commission is naturally keen to promote, because it increases the deterrent effect of competition laws and helps to compensate victims. In addition, possible solutions to alter the dynamic might be unpalatable, for example:

- Increased discounts – an increase in the percentage discounts on offer would no doubt be attractive to would-be applicants but, to work, might require a parallel increase in the already high fines that the Commission imposes on firms that do not cooperate, which might be unattractive for policy reasons.

- Negotiated settlement – another possible solution might be found in the settlement procedure, by increasing the scope for settling parties to debate and limit the precise characterisation of the infringement. Such a change, whilst outside the leniency programme, might tempt more cartel members to cooperate, first with a leniency application and then through settlement if offered. However, the Commission's position is that the settlement process is not a negotiation on the terms of its decision, so it may be resistant to such a change.

Therefore, the Commission may be content to maximise detection rates through the initiatives described above, and accept that the new normal will mean a greater investigative burden. If so, that could lead to the Commission placing greater emphasis on large-scale document reviews, of the kind used in its Credit Default Swaps investigation, in order to maintain its effectiveness as a competition authority.

Footnotes

1. For this article, the term "immunity application" has been used to distinguish leniency applications that result in immunity from fines from subsequent leniency applications.

2. Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases , at para 8.

3. Ibid , at paras 23 to 26. The first undertaking to provide evidence of significant added value will get between 30-50%; the second undertaking between 20-30%, and subsequent undertakings up to 20%. The precise percentage within each band depends on the timing and quality of the evidence provided.

4. Ibid , at para 12.

5. Graphs created from data presented in Making antitrust damages actions more effective in the EU, CEPS, EUR and LUISS, at p 28.

6. Cartel damages claims in Europe , Laborde, at p 36.

7. Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases , at para 9.

8. According to the Global Competition Review annual Rating Enforcement reports.

9. According to the Commission press release, UBS avoided a fine of approximately €2.5 billion in the Yen Interest Rate Derivatives cartel, and Barclays avoided a fine of approximately €690 million in the Euro Interest Rate Derivatives cartel.

10. For example, establishing a loss when the manipulation of interest rates has the potential to both harm and benefit third parties.

11. Power exchanges (AT 39952) and Envelopes (AT 39780).

12. See Global Competition Review article Leniency applications are "not going up" dated 20 February 2018, by PallaviGuniganti.

13. Ibid. Senior representatives of the French, Brazilian, Japanese and US competition authorities reported an increase in leniency applications; the Australian authority reported a steady level of applications; and the Canadian authority reported a fall in the number of applications.

14. Ibid. Madero noted that not applying for leniency remains " a very risky exercise " given the Commission is " putting more and more people on ex officio investigations ".

15. See Commission press release: http://europa.eu/rapid/ press-release_IP-17-591_en.htm. Other competition authorities have recently done the same, eg Austria, Sweden and the UK, while others plan to introduce whistleblower programs this year, eg Lithuania and Finland.

16. Article 11(4), Damages Directive.

17. An important exception is the regulated financial services sector, in particular in the UK, where regulated firms are obliged to notify the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under Principle 11 if they suspect a significant infringement of competition law. Given the FCA's concurrent competition law powers, a regulated firm that notifies the FCA of cartel conduct under Principle 11, would be well advised also to submit a leniency application in the UK, and therefore also to the European Commission

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.